1.4 Modern Developments: The Decline of Institutional Treatment

Significant changes to the American approach to mental disorders and the status quo of institutionalization had already begun to occur in the 1940s. President Harry S. Truman signed the National Mental Health Act in 1946, which authorized increased research and funding aimed at improving American mental health care. The Act led to the creation of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) a few years later. The NIMH is the leading federal agency for research on mental disorders and is part of the larger National Institutes of Health. The purposes of the NIMH were improved training of mental health professionals, expansion of community-based mental health care, and increased research around mental health issues. Over the next decades, the NIMH significantly expanded America’s commitment to use science to understand and treat mental disorders. Eventually, scientific progress would lead to opportunities for the treatment of mental disorders outside of hospitals.

The goal of creating asylums and state hospitals had been to provide care via a sheltering environment. This ideal was not generally realized, but even if it had been, the institutions had the flaw of removing people with mental disorders from their communities. Likewise, while early treatments for mental disorders—such as brain surgeries and shock therapy—had many drawbacks, a fundamental one was that these treatments could not be accessed in the community; recipients were required to be hospitalized. Thus, a revolutionary scientific development in treating mental disorders was the development of psychiatric medications. Unlike previous procedures and treatments that could only be performed in hospital settings, medications that treated mental disorders could be used in the community. When severe symptoms might have required patient confinement, medications to control symptoms of mental illness alleviated that need for confinement. Just as many activists were beginning to question the routine institutionalization of people with mental disorders, medication management provided an opportunity to end this approach.

SPOTLIGHT: The Oregon State Hospital, Then and Now

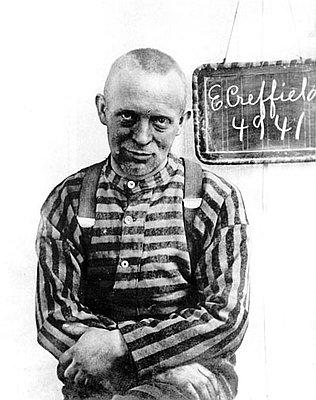

After Corvallis-area cult leader Edmund Creffield (figure 1.13) was convicted on charges of adultery, most of the members of the Brides of Christ Church were committed to what was then called the Oregon State Insane Asylum in Salem. The diagnosis was “religious hysteria,” and the women were committed by concerned family members. The year was 1904, and the asylum had only been in operation since 1883.

The Oregon State Insane Asylum was, at the close of the 1800s, considered a safe place for people to take their family members for many reasons beyond supposed insanity. Some had committed crimes, others were developmentally disabled, and many others may have simply been seen as a burden to society. A report released by the Oregon State Insane Asylum in 1896 listed the various “causes for insanity” of those admitted between December 1894 and November 1896. Among these reasons were things such as business trouble, financial trouble, loss of sleep, menopause, and even masturbation (Mental Health Association of Portland, n.d.).

Purportedly, asylum patients could receive treatment and rehabilitation and then return to society. Unfortunately, a mental institution’s idea of “treatment” back in the 1800s and early 1900s was often more detrimental than helpful, and many abuses occurred. Among these abusive treatments were lobotomies, ice baths, electroshock therapy, straightjackets, sedation, and forced sterilization.

By the middle of the 20th century, it had become apparent that the Oregon State Insane Asylum wasn’t large enough to house all of the Oregonians in need of inpatient mental health services. By 1958, the facility was vastly overcrowded with 3,545 patients, worsening the already grim conditions. This led to the opening of several new mental health facilities around the state, and the asylum officially changed its name to the Oregon State Hospital. For more history, photos, and stories from the Oregon State Hospital, you may be interested in exploring the website of the hospital’s fascinating Museum of Mental Health [Website].

Fortunately, as science and medicine have made advances, so has our understanding of effective treatments for mental disorders. Psychiatric facilities such as the Oregon State Hospital no longer administer lobotomies or other horrific “treatments” that were once the norm. Treatments for mental disorders now often include medications supplemented by individual and group therapies and activities.

As discussed in more depth in the main text, psychiatric hospitals that remain in operation have improved vastly since the time of their inception. However, the overall mental health system in the United States, including Oregon, has floundered. Recognizing the inadequacy of community mental health support, Oregon has renewed its commitment to this population—at least for the moment—with efforts such as large government investments in Oregon’s behavioral health system (Porter, 2022). It will require continued investments and sustained commitment to ensure that Oregonians who need care and social support will be able to access them.

In 1949, lithium was introduced as the very first effective medication to treat mental illness, specifically what is now known as bipolar disorder (Tracy, 2019). Another critical breakthrough occurred in 1952, when the first antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, became publicly available. Antipsychotic medications treat psychosis, a debilitating aspect of mental illness that impacts a person’s ability to distinguish what is real. People experiencing psychosis (discussed further in Chapter 2 of this text) may have delusions, where they believe something that is not real, or hallucinations, where they see or hear things that do not exist. Antipsychotic drugs treat and help control these symptoms, allowing a person to again perceive reality (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.). Chlorpromazine, marketed and more commonly known as Thorazine, effectively, though not completely, controlled symptoms of psychosis in many patients (Tracy, 2019).

Fueled by the scientific successes of the late 1940s and 1950s, as well as the growing activism against institutional treatment of mental disorders, Congress passed the Community Mental Health Act (CMHA) in 1963. President John F. Kennedy, whose sister had undergone a disastrous lobotomy 22 years earlier, signed it into law (figure 1.14). The CMHA promised federal support and funding for community mental health centers. This legislation (along with some of the other laws discussed in Chapter 3 of this text) was intended to change how services for mental disorders were delivered in the United States. Specifically, the CMHA meant to shift mental health care to communities, bringing patients along to live safely among friends and family (Erickson, 2021).

The signing of the CMHA was done with hope and good intentions for reducing the institutionalization of all people with mental disorders. In a speech to Congress promoting his agenda, President Kennedy described a plan that would change the landscape for people with mental disorders:

I am proposing a new approach to mental illness and to mental retardation. This approach is designed, in large measure, to use federal resources to stimulate state, local, and private action. When carried out, reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability. Emphasis on prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation will be substituted for a desultory interest in confining patients in an institution to wither away (Peters & Woolley, n.d.).

The CMHA anticipated the building of 1,500 mental health centers in communities, which would allow half of the nearly 600,000 people with mental disorders who were then institutionalized in state hospitals to be treated in their homes and communities instead (Erickson, 2021). However, while the CMHA did help connect many people with community-based treatment, and psychiatric hospitalizations decreased drastically in the ensuing years, the law did not meet its full promise. Only half of the expected mental health centers were ever built, and funding proved to be inadequate for the ones that were created. Although the CMHA provided dollars to build the mental health centers, it did not provide continuous funding for running them. Rather, states were expected to step up with support. However, states were quick to reduce their contributions when funding was tight or other priorities were more politically popular (Smith, 2013).

“Mental retardation” was the medical term that predated the modern and preferred terms “intellectual disability” or “intellectual developmental disorder.” As “retardation” became used as a slur, drawing on the nearly universal societal disdain for people with intellectual disabilities, the term was rejected by disability self-advocates, and eventually the general public, as well as the legal and medical establishments (Change in Terminology, 2013). If you would like to hear from advocates about the movement to use inclusive language, you can do so at this Special Olympics page [Website].

Critics argue that the CMHA was an example of “optimism without infrastructure” (Erickson, 2021). The CMHA was well-intentioned, hopeful even, but there were failures in executing its plans; in the end, not nearly enough community support was available for people to quickly leave institutions or to get the help they needed when they did leave. This was particularly true for people with more serious or severe mental disorders.

Licenses and Attributions for Modern Developments: The Decline of Institutional Treatment

Open Content, Original

“Modern Developments: The Decline of Institutional Treatment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: The Oregon State Hospital, Then and Now” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Anne Nichol.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.13. Photograph of Edmund Creffield at Oregon State Penitentiary by Oregon State Penitentiary is in the public domain.

Figure 1.14. Photograph of John F. Kennedy by Cecil Stoughton is in the public domain.