10.5 Career Rewards and Challenges

Working in the criminal justice system or in a behavioral health field—or a combination of the two—can be extremely interesting and rewarding. As you have heard in the many videos shared in this chapter, or as you may already know from your own interests and experiences, people who work in service or “helping” careers tend to do so because the work holds meaning for them. They want to improve others’ lives and make an impact in their communities.

Compassion Satisfaction

The emotional reward that comes from helping others through work is sometimes referred to as compassion satisfaction (figure 10.18). The concept of compassion satisfaction puts a name to a feeling you likely already know, and it recognizes that people derive pleasure from helping others and contributing to their communities alongside like-minded colleagues (The Center for Victims of Torture, 2021).

People in helping careers can work to grow their compassion satisfaction (which is a protective factor against the negative aspects of these jobs) by being aware of this concept and welcoming it. Specifically, a worker in a helping role should be “mindful of the experiences that can generate [compassion satisfaction], such as opportunities to ‘make a difference,’ difference-making being a key predictor of compassion satisfaction” (Stoewen, 2021). To maximize our satisfaction from work, we should intentionally savor “the hope, joys, and rewards, and the sense of meaning and purpose within our work; and the relationships that we take pleasure in, with coworkers, clients, and patients. . . . Whether held close to the heart as quiet acknowledgments or shared openly with others, deepening these experiences can grow one’s compassion satisfaction” (Stoewen, 2021). In other words, know that having and working hard at an impactful career can and should bring you fulfillment; recognize and enjoy it.

Workplace Trauma

While helping careers do bring great rewards, they can also bring challenges. One of these is the experience of trauma. Trauma has been discussed throughout this text as it relates to diagnoses (in Chapter 2) and as it relates to justice-involved people, who have often experienced a great deal of trauma. Individual trauma arising from personal experience is defined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as follows: “Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being” (SAMHSA, 2014). Note that other forms of trauma exist as well; communities can be traumatized, and trauma can become part of a group’s culture and be passed from parent to child as intergenerational trauma (SAMHSA, 2014). The people most at risk of intergenerational trauma are those who have experienced serious forms of abuse, oppression, or racial inequities. Examples are Holocaust survivors or displaced Native Americans (Dixon, 2021). These aspects of trauma are separate from the individual workplace trauma discussed here, but they can be part of a person’s entire experience that impacts how they respond to life events. If you are interested, you can learn more about intergenerational trauma here [Website].

Some of the jobs discussed in this text come with the risk of directly traumatic and stressful events. Direct trauma involves an event that directly happens to or is witnessed by the person. For example, a first responder who goes to the scene of a horrific car crash may experience direct trauma from what they witness at the scene; likewise, a person in the car crash may have direct trauma from that experience. In contrast, someone who hears about the crash on the news or sees images in reports may have indirect trauma from that intake of information (Tend, n.d.). Direct and indirect trauma tend to have different impacts on the people who experience them, but both can be harmful.

Post-Traumatic Stress from Workplace Trauma

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a diagnosis discussed in Chapter 2, stems from directly traumatic events. PTSD is generally not common, but it is far more prevalent in first responders, such as law enforcement officers, than in the general public because these workers are more likely than other people to experience direct trauma in the form of violent encounters and/or witnessing horrific events and scenes (Violanti, 2018). For example, police officers see abused children, dead bodies, and severe assaults, and they may themselves be involved in life-threatening situations, including shootings. These are all direct traumas that can give rise to the distressing symptoms of PTSD (figure 10.19) (Violanti, 2018). PTSD may be diagnosed in up to 19% of police officers (Douglas Otto & Gatens, 2022). PTSD is also startlingly common in the high-stress world of correctional officers, where up to a quarter of officers are thought to have some indications of the disorder (Dawson, 2019). Interestingly, abusive behavior conducted by officers themselves is also associated with higher rates of officer PTSD. This evidence not only suggests a (possibly underestimated) route to officer trauma but also provides yet another incentive to reduce officer violence in community and corrections environments (DeVylder et al., 2019).

A special concern with the experience of direct trauma and development of PTSD in criminal justice professionals is that PTSD can result in behavioral problems like substance abuse, aggression, and self-harm, as well as impairment of rapid decision-making capability (e.g., what tactics to use in a particular tense situation). There are clear risks to self and others that these problems could present in armed professionals tasked with resolving complex problems and crises in the community, as well as in prisons or jails (Violanti, 2018). Police officers, tragically, have higher suicide rates than other professionals, and one of the contributing factors to this risk is repeated exposure to trauma (figure 10.20) (National Consortium on Preventing Law Enforcement Suicide, 2023).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFDq2xOLILQ

See the Spotlight in this chapter on Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue in Law Enforcement for more information on the topic of officer trauma.

Effects of Indirect Trauma at Work

Just as direct trauma can give rise to certain problems, indirect trauma in the workplace—especially when exposure is repeated—can have negative effects on the people in the careers discussed here. Workers in the fields of law enforcement, corrections, and behavioral health may routinely hear about or examine evidence of others’ trauma, violence, or victimization. Workers may also engage with and emotionally invest in people with extremely challenging and sometimes entrenched life circumstances. These events are all normal parts of the helping careers, but they can be upsetting and frustrating. Over time, these events and the responses they evoke can have a cumulative negative effect on the professionals who experience them. The side effects of absorbing others’ pain are sometimes referred to as a “cost of caring.” The empathy and compassion that make workers good at their helping roles and allow them to derive such satisfaction from their work can also make them vulnerable to being harmed by their jobs (Mathieu, 2019).

Some terms commonly used to discuss the impacts of indirect trauma in the workplace are vicarious traumatization, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress. These terms describe related but distinct concepts.

- Vicarious traumatization can occur when a person in a helping career (e.g., victim services, law enforcement) is continuously exposed to victims of trauma and violence. This repeated exposure to others’ trauma changes the worldview of the worker in a negative way (Office for Victims of Crime, n.d.). People experiencing vicarious traumatization notice that their fundamental beliefs have changed so that they see the world differently than they did before (Mathieu, 2019).

- Compassion fatigue occurs when a person in a helping profession is physically and emotionally depleted by caring for others who are in significant distress, leading to a lack of compassion and empathy. Compassion fatigue occurs when helpers are unable to properly refuel and recover (Office for Victims of Crime [OVC], n.d.; Mathieu, 2019).

- Secondary traumatic stress is a term used to describe situations where workers in high-stress fields (e.g., child abuse investigators, prosecutors, therapists, shelter workers) who experience indirect trauma are impacted in a way more commonly associated with direct trauma, that is, exhibiting symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g., depression, despair, hypervigilance) (Tend, n.d.).

As examples of how these problems can occur, imagine a person who works as a child abuse prosecutor and regularly hears and reads accounts of severe, unthinkable abuse of children. The person feels very disturbed by all of this information, to the point that it interferes with their sex life and their ability to trust that their own children are safe. That is an example of vicarious traumatization; the person’s feelings about the world are shifting in a negative way. The person might also have some of the symptoms experienced by people who are directly impacted by trauma, such as feeling hopeless or having trouble concentrating (figure 10.21). This might be termed secondary traumatic stress. If the person also stops being able to talk with and sympathize with a coworker or a friend who is having a hard time, they may additionally be experiencing compassion fatigue (Mathieu, 2019).

As a practical matter, the terms secondary trauma and secondary traumatic stress are often used interchangeably with the terms vicarious traumatization and compassion fatigue, and they all refer to the negative impacts of indirect trauma. These are terms to be aware of, but the key concept for purposes of this text is that indirect trauma at work can be harmful, and that can play out in different ways (Tend, n.d.).

Workplace Burnout

Yet another term used to describe a serious workplace problem is burnout. Burnout is a state of physical and mental exhaustion in which a worker is not experiencing satisfaction and fulfillment from their job (figure 10.22). A person experiencing burnout may feel depressed, cynical, and bored (OVC, n.d.). They may also feel detached or emotionally distant, with a loss of empathy for the people they are supposed to help, a process that is sometimes called depersonalization (discussed more in the video linked in figure 10.24) (SAMHSA, 2022). Burnout may overlap with compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization, but it is different in significant ways. A person with burnout has not necessarily lost the ability to feel compassion, nor has their worldview changed. It’s a very job-specific problem that can often be remedied by a job change or perhaps by a break from the job in question (Mathieu, 2019).

The concepts introduced here are complicated and important. The two videos linked in this section are required viewing and offered to expand upon and explain the ideas in this section. The first video (figure 10.23) offers a clear explanation of the concepts of compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization, and burnout—as well as a mention of compassion resilience, another term related to compassion satisfaction discussed earlier in this chapter. As you watch, listen for and consider how and why criminal justice professionals may be particularly vulnerable to experiences of trauma, in different ways perhaps than behavioral health professionals. The second video (figure 10.24) provides additional discussion about the specific problem of burnout and how to address this problem. Although this video is not a criminal justice or behavioral health career-specific perspective, consider how the information offered would relate to the careers we discuss in this text.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aS7Rk5RFF20

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMbhM59K5FQ

If you are interested in exploring these topics further, consider starting with this optional (but excellent) TED Talk “Beyond the Cliff” by author and founder of the Trauma Stewardship Institute Laura van Dernoot Lipsky [Streaming Video]. In the video, van Dernoot Lipsky discusses the cumulative toll people may experience from absorbing suffering around them, whether that is from personal caregiving, experiencing workplace trauma, or contending with worldwide crises such as global climate change.

SPOTLIGHT: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue in Law Enforcement

Police officers have a complex and varied job. In addition to performing routine duties and interacting with the public, they respond to the scenes of heinous crimes and bring order to chaos. Myriad situations require them to provide emotional support to people impacted by crime or survivors of catastrophic events. When victims experience chaotic and horrendous incidents, police officers often represent the most reliable and prominent sources of order, information, and support at the scene.

Compassion satisfaction refers to the gratification that officers derive from helping those who suffer. Officers and other frontline professionals who experience compassion satisfaction feel a greater sense of success and increased motivation because they can appreciate the value that their services add to the community and the lives of individuals. Additionally, police officers with high levels of compassion satisfaction tend to be more committed to their duties and have greater levels of self-perceived well-being. Fortunately, many police officers report high levels of compassion satisfaction.

Officers also may experience adverse effects over time. The term compassion fatigue is often used to describe the costs that accrue in frontline personnel as a result of caring for those who suffer. It is estimated that compassion fatigue may affect around a quarter of police officers in the United States. Compassion fatigue in police officers develops due to prolonged exposure to traumatized people, and it can result in an officer becoming emotionally detached or numb in the face of others’ suffering. Within the context of police work, compassion fatigue relates to officers’ powerful desire to help or save others and to perform their duties in a manner that makes such individuals feel better and safe. However, officers’ realistic ability to do this in many cases is limited. For example, officers serving in child exploitation units may experience symptoms of compassion fatigue as a result of providing abused children with long-term support during investigations (figure 10.25).

Significantly, compassion fatigue—if left untreated—can worsen and have an incapacitating impact on frontline professionals’ well-being, decision-making ability in critical situations, and overall job performance. Compassion fatigue may adversely impact officers’ relationships with family and friends because its effects cannot be left at work. For example, what officers experience in the line of duty regarding others’ suffering may lead to emotional numbness or isolation. These “underground” emotions may reemerge in multiple problematic ways, including isolation from family, alcohol abuse, and difficulty controlling frustration and anger during interactions with others. Compassion fatigue is understood to be a precursor to post-traumatic stress disorder, and some of the symptoms are similar (Bosma & Henning, 2022).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, compassion satisfaction is negatively associated with compassion fatigue—that is, an increase in one appears to correlate with a decrease in the other. It may be that compassion fatigue symptoms (e.g., feeling overwhelmed, hypervigilant, irritable) preclude officers from experiencing compassion satisfaction. Officers with high levels of compassion satisfaction may better appreciate the importance of their services despite their exposure to overwhelming experiences. Using various techniques to strengthen compassion satisfaction may thus reduce the experience of compassion fatigue.

Several approaches foster police officer wellness and help build work-related satisfaction:

- Practicing self-care. Officers should be taught, as part of their police training, methods of effective self-care, such as controlled breathing, mindfulness, and journaling.

- Appreciating the positives. Departments should develop programs that identify and celebrate achievements and moments of gratitude. Police officers may view these positives as routine parts of their work, but they benefit from taking time to reflect upon and feel grateful for the services they provide for their communities.

- Training around trauma. Police organizations should emphasize training for law enforcement professionals that allows them to better respond to people who have been traumatized. Increasing police knowledge and enhancing responses helps officers achieve greater confidence and a sense of effectiveness, leading to professional satisfaction.

- Peer Support. Officers often need help but hesitate to request or accept it. Peer support programs may be one solution. An officer may be more comfortable approaching a peer who understands the context and has experienced the same stressors (Community Policing Dispatch, 2023).

Building Resilience

Counteracting burnout and problems associated with indirect trauma is more likely when professionals are aware of risks and proactive in maintaining protective factors. Certainly, recognizing and using the power of compassion satisfaction to stay energized and positively connected to our work can counterbalance negatives in the workplace (Stoewen, 2021). When negatives do occur, resilience is key to minimizing their impacts. Resilience is the process of adapting well in the face of adversity or significant stress (figure 10.26) (OVD, n.d.).

Resilience is not an innate quality; rather, resilience involves using internal and external resources and strategies to adapt to adverse events or conditions. A resilient person might regularly draw upon their personal sense of optimism (an internal resource) as well as a wise mentor (an external resource) and use strategies such as maintaining work-life balance and engaging in self-care (discussed below) (Stoewen, 2021). Additionally, just as a person can absorb others’ trauma, they can also experience vicarious resilience, which is when one benefits from the secondhand experience of others’ success in overcoming adversity. Vicarious resilience is a positive and empowering—rather than negative—result of witnessing the experience of someone who has been through trauma and emerged a survivor. (OVC, n.d.; Killian, 2023). “[Resilience] is actually a learned competency; one that—with awareness, intentional pursuits, and lived experience—can be strengthened over time” (Stoewen, 2021). Highly resilient people “are able to remain stable and function well during stress and recover from stress. They can ‘bounce back’ from difficult experiences and move on despite the challenges” (Stoewen, 2021).

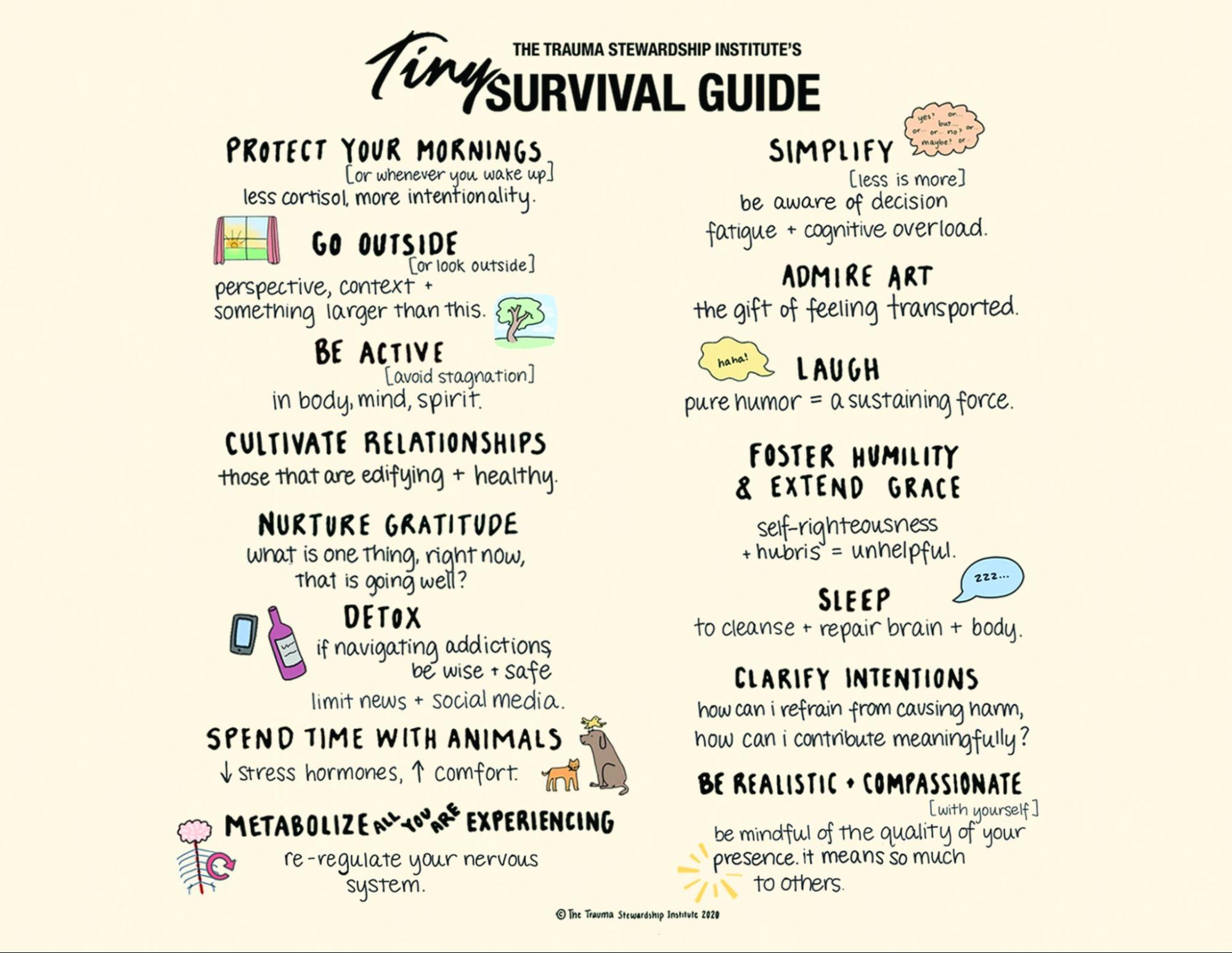

One key to building resilience—and maintaining the ability to care for others—is the practice of self-care (Stoewen, 2021). Self-care refers to deliberate actions and behaviors that enhance mindfulness and well-being. Take a look at the “Tiny Survival Guide” reproduced in figure 10.27. This resource was created by the Trauma Stewardship Institute and offers several strategies for self-care. Consider what strategies you might employ, now or in the future, to maintain your health.

Although workers need to do what they can to remain healthy and cope with the realities of a career in “helping,” it is also true that individual workers are limited in what they can do for themselves. Employers and organizations are, ultimately, determinative of the workplace environment. Organizations that rely upon the labor of people in helping professions need to support their workers in managing their exposure to trauma and provide ongoing education and support around these issues (Mathieu, 2019).

Licenses and Attributions for Career Rewards and Challenges

Open Content, Original

“Career Rewards and Challenges” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Second from final paragraph regarding self-care by Kendra Harding, revised by Anne Nichol, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“SPOTLIGHT: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue in Law Enforcement” is adapted from “Police Compassion Fatigue” by Konstantinos Papazoglou, Ph.D., Steven Marans, M.S.W., Ph.D., Tracie Keesee, Ph.D., and Brian Chopko, Ph.D., FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin is in the Public Domain. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include rewording and expanding the content.

Figure 10.18. “If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion” by Nick Kenrick is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 10.19. “Compassion Fatigue Among Officers” by FBI LEB is in the Public Domain.

Figure 10.21. Photo by christopher lemercier is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 10.22. “Woman Suffers Burnout At Work.jpg” by CIPHR, is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.20. “A Psychologist and Former Officer on Mental Health and Suicide | We Are Witnesses” by The Marshall Project is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.23. “Recognizing Compassion Fatigue, Vicarious Trauma, and Burnout in the Workplace” by Policy Research Associates, Inc is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.24. “3 signs that you’ve hit clinical burnout and should seek help” by Big Think is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.25. Photo by Wynand van Poortvliet is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 10.26. “Sprout makes way through sand” is designed by FreePik.

Figure 10.27. “Tiny Survival Guide” © the Trauma Stewardship Institute is all rights reserved and included with permission.