2.3 Introduction to Specific Mental Disorders

Although criminal justice professionals do not diagnose mental disorders, they should certainly expect to interact respectfully, in various capacities, with people who experience one or more of these disorders. Indeed, as we will discuss further in Chapter 10 of this text, many criminal justice professionals are at heightened risk of developing certain mental disorders themselves. For these reasons, all students in the criminal justice field will benefit from familiarity with the diagnoses introduced in this chapter.

To further explore any of the disorders touched upon in this chapter, take a look at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [Website]. The NIMH, a federal agency for research on mental disorders, offers current information on specific disorders and provides the content for much of this chapter.

The summaries of disorders presented in this chapter are necessarily brief and are intended for criminal justice students. Students who intend to work directly with people accessing behavioral health services will want to learn more about these disorders. There are some very interesting disorders omitted here: eating and sleeping disorders, specific learning disorders, and others that relate to every aspect of life. Included in this chapter are some diagnoses that are more likely to be encountered in the criminal justice system or that may be of particular interest to the criminal justice student.

Anxiety Disorders

Occasional anxiety about matters such as health or family is a normal part of life. Many people identify as worriers. But anxiety disorders involve more than temporary worry or fear. For people with an anxiety disorder, the worries or fears are excessive and do not go away, interfering with daily activities such as jobs and relationships.

There are several specific types of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Specific fears or aversions, called phobias, also fit under this category. The distinctions between these diagnoses are beyond the scope of this text, but if you are interested, take a look at the National Institute of Mental Health page on the topic of anxiety disorders [Website]. Note that a person can have multiple forms of anxiety disorder or an anxiety disorder alongside other disorders.

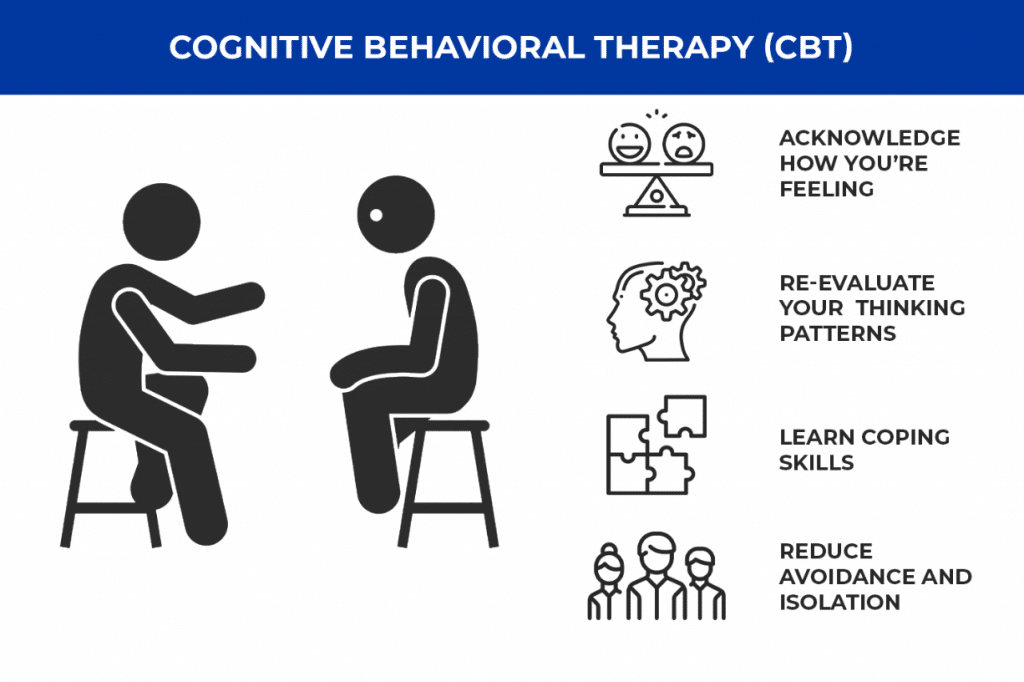

Anxiety disorders are usually treated with psychotherapy (also known as “talk therapy”), medication, or both. One specific therapeutic technique often used to help people with anxiety disorders—as well as many of the other disorders in this chapter—is Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (figure 2.4). CBT is a set of therapeutic techniques that teaches people different ways of thinking, behaving, and reacting to situations. Exposure therapy, during which a person confronts their fears while engaging in relaxation exercises, would be an example of a CBT approach used to treat anxiety. CBT has been well studied and is considered the gold standard for psychotherapy.

Another treatment for anxiety is medication. Medications do not cure anxiety disorders, but they can help relieve symptoms. The most common medications prescribed for anxiety are antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications (such as benzodiazepines), and beta-blockers.

Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders

The DSM-5-TR (like the DSM-5) categorizes a few disorders under the heading of Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders. Trauma refers to a situation that physically or emotionally harms a person to the extent that it impacts their well-being. Trauma-related disorders are unique in being triggered by the person’s exposure to stressful events. The most well-known of this group of disorders is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Anushka et al., 2017).

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. This includes combat veterans and people who have experienced or witnessed an assault or a disaster. Sometimes, learning that a friend or family member experienced trauma can cause PTSD. People who work as first responders, such as police officers, can develop PTSD based on exposure to trauma in the course of their work, a topic discussed more in Chapter 10 of this text (American Psychiatric Association, 2022c). While it is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation, most people recover over time. Those who continue to experience problems may be diagnosed with PTSD. While about 6 out of every 100 people overall will experience PTSD at some point in their lives, women are more likely to develop PTSD than men.

Diagnosis of PTSD requires that a person experience a set of symptoms that start after trauma and linger over time, interfering with aspects of daily life, such as work or relationships (figure 2.5). Specific symptoms can vary, but the diagnosis requires symptoms from four categories: reexperiencing (e.g., flashbacks or dreams); avoidance (e.g., refraining from acts or places that are reminders), reactivity (e.g., being easily startled, always distracted), and thinking or mood (e.g., memory challenges or negative thoughts).

Typical treatments for PTSD are psychotherapy and/or medication. Effective PTSD therapy works toward the identification of triggers and management of symptoms; it may also help people make sense of their traumatic experience and deal with misplaced feelings of guilt or shame. Medications can address some symptoms such as sadness or sleeplessness. Occasionally, people with PTSD experience ongoing trauma, such as in an abusive relationship. For them, treatment should address both the source of trauma and the symptoms of PTSD.

It is important to emphasize that not everyone who experiences trauma goes on to develop PTSD. Certain types of trauma, like interpersonal violence, are more likely to cause PTSD than other traumas, like natural disasters. Social support and a sense of community are protective factors that can reduce the risk of PTSD (Spielman et al., 2020b). Certain groups of people are more likely to develop PTSD because they are more likely to bear the strain of isolating events that will lead to PTSD. Black men, for example, are more likely to witness and personally experience violent victimization than non-Black males, and they are more likely to have PTSD (Kilpatrick et al., 2017). Women who are incarcerated in prison are also much more likely to have PTSD than the general population, with a prevalence estimated at over 20% (Facer-Irwin et al., 2019). If you would like to know a little more about PTSD, you may watch the video linked here (figure 2.6).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoJBvXAUvA8

SPOTLIGHT: What Is Trauma?

Bessel van der Kolk, psychiatrist and author of The Body Keeps the Score, is an expert on the impact of trauma on people’s lives. Watch the 7-minute video clip in figure 2.7 where van der Kolk describes trauma and discusses its effects. Pay particular attention to van der Kolk’s observations about the importance of societal support and personal relationships in mediating the impact of trauma. Does the video impact your understanding of the concept of trauma? What changes can you imagine in your community or in the larger world that would reduce problems associated with trauma?

Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative disorders involve an individual becoming separated, or dissociated, from their core sense of self, resulting in disturbance of their memory and identity. The DSM specifies that to qualify as a disorder, this “disturbance” cannot be related to a cultural practice, such as a spiritual practice that involves being “possessed” and is accepted in the person’s community. This clarification in the diagnostic criteria exemplifies the effort in the updated DSM to avoid the medicalization and stigmatization of a range of healthy human experiences (American Psychiatric Association, 2022a).

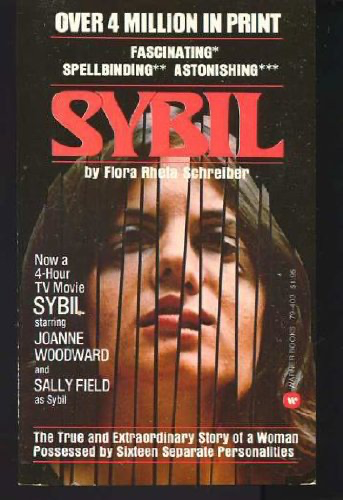

Dissociative disorders listed in the DSM-5-TR include dissociative amnesia—the total forgetting of events, often traumatic ones—and dissociative identity disorder (DID)—a rare but intriguing disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2022a). DID, which was formerly called “multiple personality disorder,” may be diagnosed when a person exhibits two or more separate and distinct personalities or identities that alternately take control of the person (NAMI, 2023a). The person with DID will experience memory gaps, such as not recognizing belongings, and display differences in attitudes and preferences as their identities shift back and forth. The symptoms of DID can cause significant distress and problems in daily functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2022a). DID has long been a controversial diagnosis, partly because it was highly popularized in the book Sybil, a best-selling 1970s “true story” about a woman with 16 different personalities (figure 2.8). The media attention from the book, and a later movie starring Sally Field, led to a public fascination with—and a vast overdiagnosis of—multiple personality disorder. Before Sybil was published, only about one hundred cases of the disorder had ever been recorded, but thousands were diagnosed in the decade after the book’s publication. As it turned out, much of Sybil’s story was likely embellished, if not outright untrue (Haberman, 2014).

Aside from the drama around Sybil, dissociative identity disorder is in the DSM as a legitimate—though exceedingly rare—diagnosis that is tied to a history of severe childhood abuse and trauma and that mainly impacts women. People who develop PTSD due to trauma can sometimes exhibit dissociative symptoms without a full diagnosis of dissociative disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2022a). Treatment for dissociative disorders or symptoms generally involves therapy and occasionally hypnosis. Medications do not treat the disorder itself but can be used to deal with symptoms such as depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2022a).

Licenses and Attributions for Introduction to Specific Mental Disorders

Open Content, Original

“Introduction to Specific Mental Disorders” (introductory paragraphs) by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Anxiety Disorders” by Anne Nichol is adapted from “Anxiety Disorders” by the National Institute of Mental Health, which is in the Public Domain. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include revising and condensing the content.

“Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders” is adapted from “What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?” by the National Institute of Mental Health, which is in the Public Domain. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include revising, expanding upon, and condensing the content.

“SPOTLIGHT: What is Trauma?” by Kendra Harding is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include minor revisions.

“Dissociative Disorders” by Kendra Harding is adapted from “15.9 Dissociative Disorders” by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, and Marilyn D. Lovett, Psychology 2e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include substantially revising and expanding the content.

Figure 2.4. CBT Veterans by JourneyPure Rehab is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.5.“Žodis Debesis, Ptsd, Sąmoningumas, Parama – nemokama nuotrauka” by Maialisa is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.6. “What is PTSD” by American Psychiatric Association is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.7. What is trauma? The author of “The Body Keeps the Score” explains | Bessel van der Kolk | Big Think by BigThink is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.