4.4 Diversion from the Criminal Justice System

One response to the problem of criminalization is diversion, which is when a person is identified at some point (early or late) in the criminal justice system and provided with a pathway out of that system. Ideally, the person is shifted to an alternative form of supervision, support, or treatment. Referring back to the example of “Jamie,” an early diversion might have involved a mobile mental health team (rather than police) responding to the park, connecting Jamie with mental health and housing resources—and perhaps food or some other comfort—and meeting Jamie’s needs rather than making an arrest. Regardless of Jamie’s responsiveness to help, the escalation might not have occurred, and Jamie would never have had the opportunity to assault a jail deputy. Jamie would have been diverted from the criminal justice system.

Diversions are not exactly an alternative to or rejection of the criminal justice system. Diversions, instead, are part of that system. Diversion usually requires a person to have at least a brush—and maybe full engagement—with the criminal justice system, whether that is as a subject of a 911 call from a community member, an arrest, or a conviction. Once a person is identified as a candidate for diversion out of the criminal justice system, the person is directed to a program or pathway suited to their needs. Thus, diversion relies upon the infrastructure of the criminal justice system to fulfill its purpose.

Most diversions seem imperfect, and that is at least in part because they are merely responses to the already unfolding problem of a person becoming justice-involved. The diversion recognizes that problem and ideally lessens its impact, but the underlying issue is not likely resolved. For example, “Jamie” may need help of some sort again in the future, and police are the most likely responders—setting everyone up for a repetition of events. Alternately, perhaps Jamie will respond to and benefit from resources, and there will not be a future call. In any case, an appropriate diversion ensures that Jamie will not spend months in jail or the hospital for a minor offense this time. Furthermore, the financial cost of diversion is relatively negligible, and an early diversion that takes place at the time of the first response (such as a response by someone other than police) reduces the chances of a violent confrontation in which Jamie or responding officers are injured.

Diversion can occur at different points during a person’s involvement in the criminal justice system. Diversion may occur very early, allowing a person to fully avoid engagement in the system. In this case, the diversion might be as simple yet powerful as outreach from a community mental health resource to a person who is experiencing a crisis, or the decision of a law enforcement officer to refer an unhoused community member to a shelter (figure 4.7).

Diversion can also come later, such as when it takes place in alternative courts for those with mental disorders. In this case, a person has likely faced arrest and been referred to the district attorney for charges. A referral to a specialized court may give this person the opportunity to fulfill treatment or supervision requirements to avoid conviction on those charges. In other instances, a person may be deep in the criminal justice process, and diversion may present as planning that helps a person entering the community after incarceration find treatment and achieve stability.

Which moment is “best” diverting a person away from the criminal justice system is a point of much discussion and disagreement. Many contend that early diversion is crucial to avoid or minimize the risk, trauma, and stigma that can result from engagement in the criminal justice system. Others wonder whether accountability may increase the likelihood of successful diversion once a person has become engaged in the criminal justice system. Clearly, there are risks and benefits to various approaches to diversion, but it is safe to say that diversion at any point is likely an improvement over diversion at no point.

SPOTLIGHT: Solutions Not Suspensions

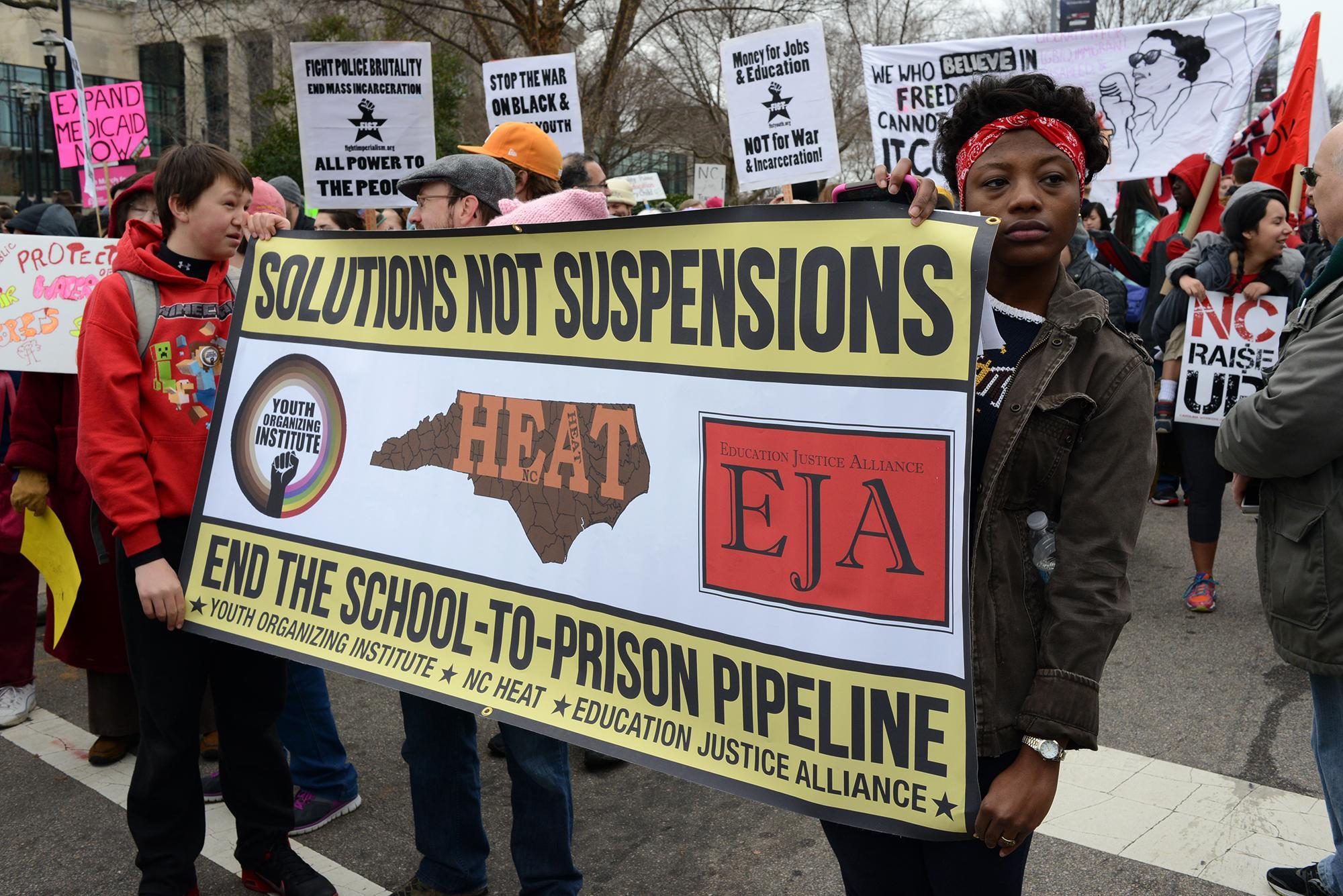

Disciplinary actions in K-12 schools are meant to curb bad behavior and hopefully deter future disruptive incidents. Unfortunately, some school disciplinary approaches push students down a path that sets them up for failure, sometimes feeding them directly into the justice system. This is referred to as the school-to-prison pipeline, and it is a source of anger and frustration for many communities (figure 4.8).

For example, consider a young student who frequently loses his temper during class and becomes destructive. The rest of his classmates are ushered from the room while support staff are called in to handle the student’s behavior. After too many incidents like this, the student is suspended for several days. Because of his suspension, he falls behind his classmates on his schoolwork and his academic progress. School failure increases his frustration, resulting in more outbursts and more disciplinary action. His classmates now perceive that something is “wrong” with the student, and he is further isolated from his peers, leading to even more behavioral problems. Eventually, the police get involved, and the student is now engaged with the juvenile (or criminal) justice system (figure 4.9).

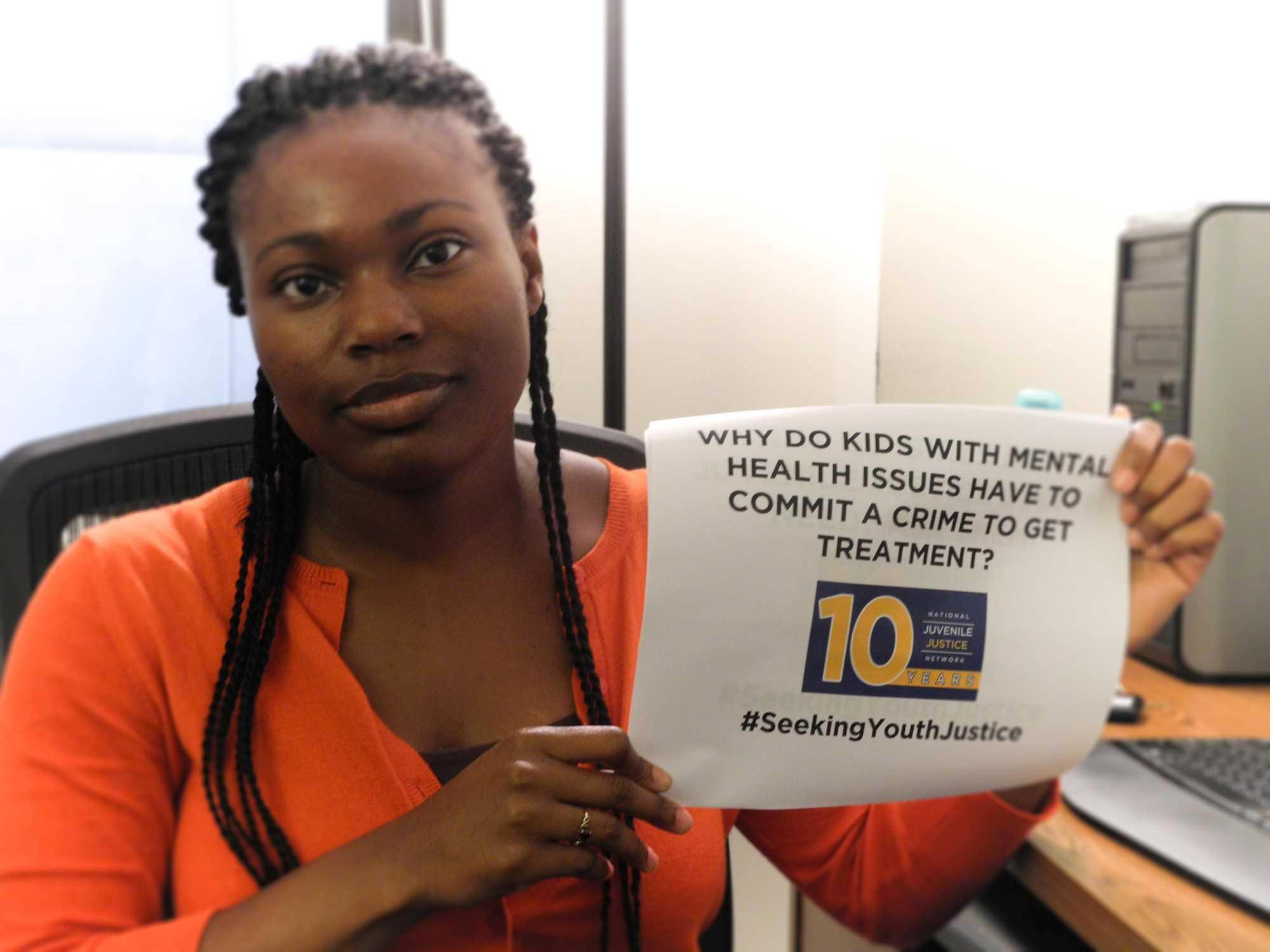

Scenarios like this happen all too often, resulting in the punishment—rather than the treatment and support—of students with mental disorders. Students of color and those with a history of poverty, abuse, and neglect are particularly vulnerable to this mishandling. Meanwhile, involvement in the justice system does not resolve behavioral health issues; it exacerbates them.

Criminal justice involvement for youth is understood to be connected to adverse childhood experiences, or potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (Graf et al., 2021). These adverse experiences can have lifelong impacts on young people; they have been linked to health complications, education problems, and work issues, in addition to mental disorders and criminal justice system contacts. Given the connections between trauma, mental disorders, and justice system involvement, the large number of justice-involved juveniles who meet the criteria for a mental disorder is less surprising. Some researchers estimate that as many as 70% to 95% of incarcerated youth have mental disorders (Ojukwu, 2022).

Certainly, there are better options for supporting students managing mental disorders and/or trauma, such as providing mental health services and other proactive social support for children in our K-12 schools instead of office referrals for punishment (Collins, 2015). While an estimated 20% of all children have a diagnosable mental health disorder, less than a third of those children go on to receive any sort of mental health services.

Imagine the potential preventive impact of treatments that support our young people and help them avoid the myriad documented consequences of untreated mental disorders, which can include everything from lowered academic performance to increased dysfunctional relationships to higher rates of unemployment and incarceration. Then, consider the following questions:

- If schools focused on positively supporting students with mental disorders from an early age, do you think we would see fewer violent incidents at schools and in our communities?

- Could robust mental health and disability support in schools function as true “diversions” that steer children away from—rather than into—the juvenile or criminal justice systems?

Licenses and Attributions for Diversion from the Criminal Justice System

Open Content, Original

“Diversion from the Criminal Justice System” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: Solutions Not Suspensions” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Anne Nichol.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.7. MPDC Officer in conversation with homeless man by Elvert Barnes is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 4.8. February 2014 Moral March On Raleigh 36 by Stephen Melkisethian is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 4.9. Photograph of a young woman by National Juvenile Justice Network is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.