6.3 Establishing Competence

Competence is not just a legal principle; it is something that must be ensured for each individual in the criminal courts. If a serious question is raised about a defendant’s competence, the defendant must be evaluated by a mental health professional to determine their ability to proceed and advise the court on the required next steps (Pinals & Callahan, 2019). In our example case, Jose Veguilla’s new defense attorney, at that very first hearing, recognized that Veguilla was likely not competent. The attorney objected to the case moving forward at all. The judge did complete the hearing, advising Veguilla of his charges, and then ordered Veguilla to be sent to a psychiatric hospital for a formal evaluation of his competence to stand trial (Thompson, 2023).

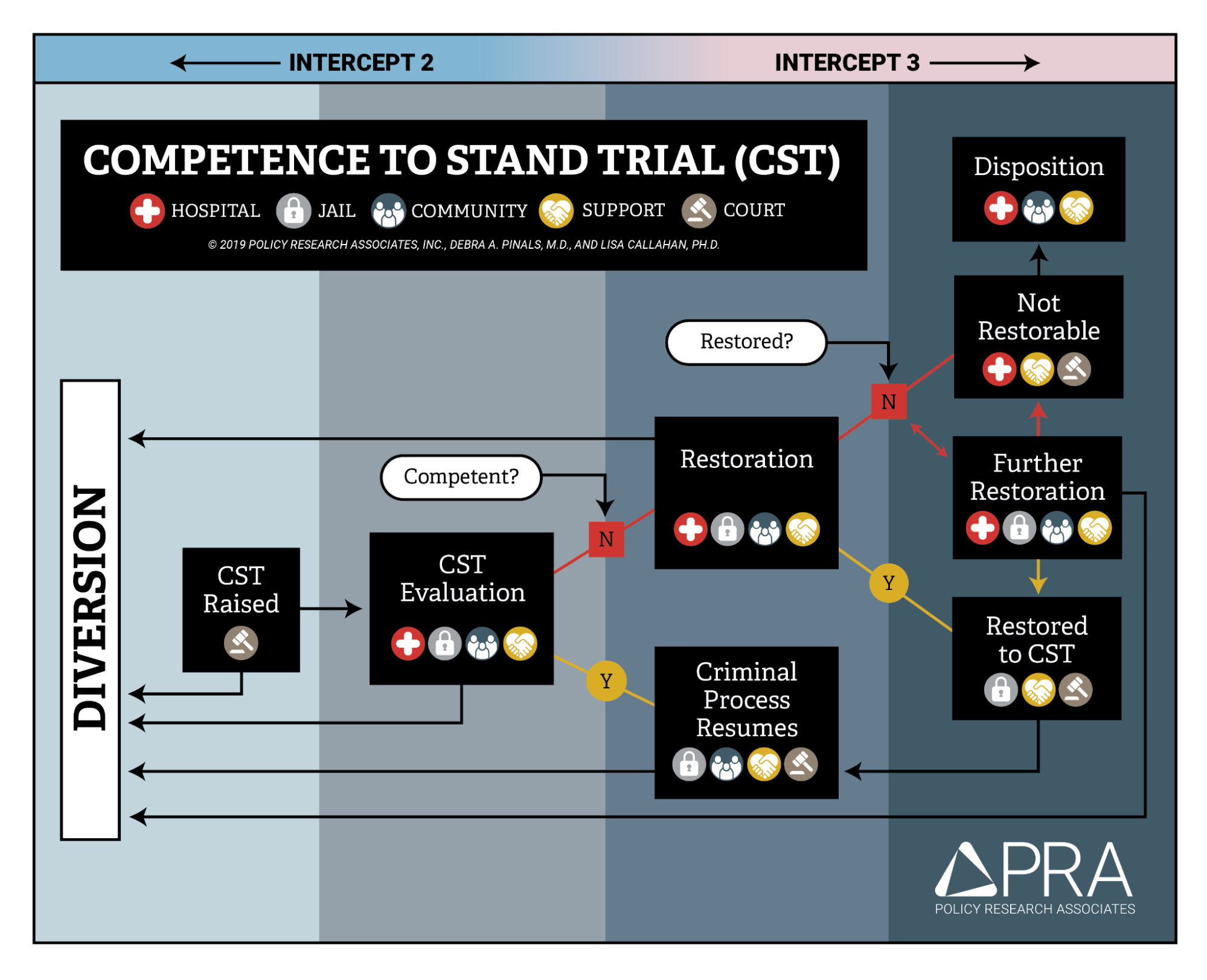

The flowchart in figure 6.5 illustrates the progression of the “aid and assist” or competence to stand trial (CST) process. The chart shows the key points in the competence process as (1) the point where the issue of competence is raised; (2) the competency evaluation; (3) the attempted competency restoration(s), if necessary; and (4) eventual resumption of the criminal process, where possible. Each of these steps is discussed in the text of this chapter. In the flowchart, icons indicating the roles of participants are included in each step of the competence process, showing that after the issue of competence is raised in court, multiple stakeholders must engage and cooperate at every step to resolve competence issues.

The flowchart also shows, with arrows, that a person can be diverted out of the criminal system at any point in the competency process. The corresponding intercepts in the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM), discussed in detail in Chapter 4, are indicated at the top of the figure 6.5 flowchart. Exploration of competence often occurs during SIM Intercept 2, where there are opportunities for dismissal of charges, while cases that move forward in the competence process also move more deeply into the criminal justice system, into SIM Intercept 3 or beyond. Less serious cases may be considered for alternative handling rather than pursuit of competence, while more serious cases may demand significant effort to complete the criminal process.

Assessing Competence

When an accused person is clearly very mentally ill or disabled and wholly unable to comprehend the reality of their situation, it may seem obvious that they are not competent to proceed with their case in court. This would seem the situation for Jose Veguilla, who suffered from severe dementia. It would likewise seem true for any defendant who is extremely impaired by a mental disorder—for example, a defendant operating on delusional beliefs, such as insisting that they are an undercover operative in a military action rather than a defendant on trial. Nonetheless, a determination about competence has an enormous legal impact, with the power to halt a murder trial, and so it must be made with care and based on the evidence and the law.

The key piece of evidence in a competency determination is an evaluation of the defendant. A typical competency evaluation is performed by a licensed mental health professional, generally a psychologist or psychiatrist. The evaluator considers the person’s mental capability in light of the legal standard for competence in the relevant jurisdiction and then offers a professional opinion as to whether the person is legally competent. A competency evaluation contains information that supports the evaluator’s conclusion as to competence and allows a judge to use the evaluation as the basis for a legal decision. Specifics would include:

- a mental status examination that looks at whether the person has basic orienting facts, such as who and where they are;

- a description of psychiatric symptoms the person is experiencing, such as loss of memory, hearing voices, or having delusional beliefs; and

- an assessment of the person’s understanding of the criminal proceedings, including their knowledge of the charges against them, possible outcomes in court, and perhaps the pros and cons of engaging in a plea agreement.

It is also important for a competency evaluation to explicitly address whether the evaluator believes that the person is making up or exaggerating symptoms for some benefit, such as avoiding criminal processing, which is known as malingering (discussed in Chapter 2; Or. Admin R. 309-090-0025).

To think about how a competency evaluation process looks in practice, imagine a defendant who has bipolar disorder and is symptomatic in the midst of a manic episode (see the discussion of bipolar disorder in Chapter 2). The defendant might meet the requirement of factually understanding the proceedings against them, but their racing thoughts, delusional beliefs, and overall uncontrolled emotions might prevent them from working effectively with their defense attorney. The defendant might be unable to track discussions about their case or be constantly trying to fire their attorney. The defendant’s active mental illness may prevent them from behaving in an orderly way that would allow them to attend their courtroom proceeding. In this case, the evaluator may state their opinion that the person is not competent to proceed and needs treatment to gain competence.

Each state’s practices vary in terms of requirements for determining competence, and the federal system has its own separate set of rules. Regardless of specifics, these procedures must, at a minimum, protect a defendant’s due process rights. Procedures also should consider the safety of the public, concern for victims, and the integrity of the criminal justice system. Oregon examples are provided here for purposes of illustration.

In Oregon, the law governing competency determinations is Oregon Revised Statute 161.370 [Website], and the process is formally called a “Determination of Fitness to Proceed.” You can click the link provided if you are interested in seeing the statutory language. The competency evaluation performed as part of an Oregon court’s determination is typically called either an “aid and assist evaluation” or a “370 evaluation” based on the local statute number. Consideration of malingering (or “faking” to manipulate outcomes, an issue discussed in Chapter 2) is specifically required by Oregon law governing these evaluations (Or. Admin R. 309-090-0025). If the defendant is evaluated and found competent to proceed, they will be allowed to proceed with their criminal case.

If an Oregon criminal defendant lacks competence, the parties have several options for going forward. Among the available options listed in the Oregon statutory scheme are:

- pausing to “restore” the accused person’s competence, anticipating a resumption of the criminal case (discussed later in this chapter);

- dismissing the charges against the person; and/or

- beginning the process of hospitalizing the person for involuntary mental health treatment, or civil commitment, which is discussed in Chapter 9 of this text.

Which of these options is appropriate will depend on the nature of the underlying charges and the specific condition of the defendant.

Restoration of Competence

You have learned that the mere presence of a mental disorder does not prevent a person from being arrested or charged with a crime, though diversion opportunities (discussed in Chapter 4) may offer police or prosecutors an alternative to criminal proceedings in some cases. However, if a person is headed to criminal court, lack of competence is a complete bar to continuing the legal case; an accused person cannot go forward to trial or any other resolution (e.g., a guilty plea) unless or until they are competent to do so. The process of treating a person with the objective of making them competent, or able to aid and assist, is referred to as restoration of competence (figure 6.6).

Restoration involves targeted treatment to take an accused person from an irrational or confused state to one of adequate understanding of the criminal process and their particular situation. Some people are not good candidates for restoration. The elderly dementia patient Jose Veguilla, who we have discussed throughout this chapter, cannot be made competent, as several professionals have opined; rather, his memory and ability to aid and assist in his defense worsen over time as his dementia progresses. This presents a particular problem that is discussed further in Chapter 9 of this text: the defendant who is not restorable, or never able to proceed (Thompson, 2023).

However, most defendants are better suited to competency restoration. For example, the competency evaluation of a person experiencing a manic episode, such as that imagined in the previous section, involves a mental health professional finding that a defendant lacks the ability to aid and assist their attorney. In this type of case, restoration should strive to address areas of deficit identified by the evaluator (e.g., racing thoughts, delusional beliefs, and limited attention span). Restoration is specifically meant to help the person meet competency requirements so that they can resolve their case. Restoration treatment is not focused on the overall mental health of the person, although it often requires psychiatrically stabilizing the person with medication and therapy. If psychiatric symptoms such as voices, delusions, or mania are preventing a person from meeting the standard of competence, those symptoms need to be targeted in restoration treatment. If the person refuses medication that is necessary for restoration, medication may be given on an involuntary basis under some limited circumstances (Sell v. United States, 2003).

Another part of competency restoration treatment is the teaching of legal terms and concepts. For example, a person may be instructed about the role of their lawyer, what confidentiality means, what a judge and jury do, and other general information about the criminal justice system. In its fact sheet on the topic, the Oregon State Hospital (figure 6.7) describes restoration as potentially including other therapeutic services, such as occupational therapy to work on daily living skills (cooking and managing personal finances), educational services, and medical and dental services (Oregon Health Authority, 2019).

Restoration can take place in a variety of settings, including in state psychiatric hospitals, such as the Oregon State Hospital, where this process is generally referred to as treatment under a “370 order,” again referring to Oregon’s particular competency statute. Commitment to a psychiatric facility for restoration of competence is discussed more in Chapter 9 of this text, along with other types of civil commitments.

In Oregon, as well as other jurisdictions, people with serious mental disorders who are accused of crimes can face significant delays in resolving their charges when there are questions about their competence and hospital transfers are involved. For example, a person may wait in jail for potential resolution of their case, which becomes impossible due to competence questions; they then await admission to a hospital for a competency evaluation, only to return to jail and then wait again for restoration treatment, if ordered. Defendants such as Jose Veguilla exemplify an extreme version of this issue, where restoration to competence is impossible, but the case involves very serious crimes that no victim or prosecutor is likely to want to dismiss or set aside.

In Oregon, as in most other states, the law provides for restoration in the community under the supervision of mental health providers, rather than in a hospital setting, if that can be done safely (Or. Rev. Stat. § 161.370). Usually, either the competency evaluator or another designated evaluator will offer an opinion as to whether the defendant needs to remain in the hospital or whether treatment can occur in the community. Often, a person may be incompetent to proceed to trial, but they can be safe in the community while receiving care.

A number of states have jail-based restoration programs, avoiding transfers to a state hospital or other facility for restoration, and bypassing the risks of community placement (figure 6.8). Providing restoration services in jail is controversial, with proponents emphasizing the immediacy of treatment available and opponents noting the lack of a therapeutic environment, among other problems. Of significant concern is the potential for prolonging the incarceration of a person because of a mental disorder (Ash et al., 2020).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=duX_28uaOKE

Alternatives to Restoration

As noted previously, restoration is only one of the options available to the parties when an accused person is not competent to proceed with their case. Other options (outright dismissal of charges or pursuit of a civil commitment, described in Chapter 9) would remove the case from the criminal courts more permanently, possibly to the detriment of victims, as well as the larger community. Victims deserve resolution in cases where they have been harmed, and important goals of the criminal justice system are not met if offenders are released into the community without accountability and supervision.

However, outright dismissal of criminal charges may be a reasonable or preferred option in some cases. For non-violent or lower-level charges, the lengthy process of evaluation, restoration, and resumption of court proceedings might take far longer than the person would ever have been jailed for an underlying charge of theft or trespass. Thus, insisting on continuing a minor case—with all of the delays involved—arguably places an unfair burden on people with mental disorders. In these cases, dismissal can be a just resolution, especially if support can be offered to avoid reoffense.

Licenses and Attributions for Establishing Competence

Open Content, Original

“Establishing Competence” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.6. Photograph of group therapy by Mangionekd is used under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 6.7. Photograph of Oregon State Hospital Sign by Ocsdog is used under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.5. Competence to Stand Trial (CST) Flowchart by D.A. Pinals and L. Callahan, Policy Research Associates, is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 6.8. Jail Based Competency Treatment Program by the San Diego Sheriff’s Department is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.