6.4 Insanity as a Criminal Defense

The first section of this chapter discussed scenarios in which an accused person’s mental disorder impacts their ability to navigate the court process. Backing up in time, the person’s mental state when they committed the offense (often months or years before the resolution of the case) can be an important factor in how the case is ultimately resolved. The lack of mental capacity to commit a crime is a rare but important defense to criminal conduct. When a person asserts the insanity defense, they typically admit that they did the accused act, but they assert (and must prove) that they are not guilty of a crime due to the influence of their mental disorder on their conduct.

The mere presence of a mental disorder diagnosis does not make a person legally “insane” for purposes of the insanity defense. A mental disorder is a medical diagnosis (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, intellectual disability). People who have these diagnoses live productive and prosocial lives in our communities, and people with these diagnoses sometimes engage in criminal behavior for which they should be held accountable. But occasionally—rarely—certain mental disorders can render a person legally insane under the law in their jurisdiction, and that can provide a defense to otherwise criminal conduct.

When a person is found not guilty by reason of insanity, as it is termed in many states, or guilty except for insanity (GEI), as it is called in Oregon, the result of this verdict is generally that the person is committed by the judge to the care of the state for services and supervision. For more serious offenders, care is generally provided in a restrictive hospital setting. Some state laws allow care to be ordered for an indeterminate period until the person can be adjudged safe to be unsupervised. Other states require care for a designated period, such that the person may be, and often is, committed for the maximum time that they would have been sentenced to prison had they been criminally convicted of that particular offense. Oregon is one of the latter states, which uses specific periods of commitment. So, if a person in Oregon is found GEI for the burglary of a residence, they may be committed to the state hospital for up to 20 years—the maximum prison time for a burglary conviction—but commitment can end early should the person no longer meet the legal standard (of dangerousness due to a mental disorder) to remain under supervision. Although these “criminal” commitments, discussed in more detail in Chapter 9, may feel or look like a punishment, a commitment order is not a criminal sentence, as the person has not been convicted of a criminal offense. Rather, the basis for the court order and the objective of a commitment is to provide care for the person and to minimize the person’s danger to others as well as themselves.

Excuse Versus Justification Defense

Certain criminal defenses involve a defendant admitting they did a particular act but claiming that circumstances surrounding the act remove criminal responsibility or guilt for the act. The two groups of defenses in this category are justification defenses and excuse defenses:

- Justification defense: I killed that person because I actually needed to, so I am not criminally responsible.

The accused person has committed no crime because their behavior was warranted, or justified, by the circumstances. The behavior is not wrong, but right, in this case. The classic example of justification is self-defense, where the defendant was being attacked and in response killed the alleged victim (the attacker) to save their own life. The accused has not committed a crime; they were justified in defending themselves.

- Excuse defense: I killed that person, but I didn’t intend to do something wrong, so I am not criminally responsible.

The accused person has done something wrong, but due to the circumstances or their understanding of that act, it is not in the interest of justice to find them guilty of a crime. Perhaps the person was forced at gunpoint to rob a bank (the defense of duress) or perhaps they chose to commit a burglary to feed a starving child (the defense of choice of evils). Criminal law should hold people accountable for doing bad things—but not necessarily punish people who didn’t want to do bad things.

Insanity is an excuse defense because the act the person is charged with was wrong, but the person did not know, understand, or intend that wrong, depending on the facts of the case. For example, an insanity defense case might involve a defendant who killed a person they truly believed (incorrectly, due to a mental disorder) was attacking them with intent to kill, while the victim was (actually) an innocent bystander on the sidewalk. We might say the defendant has committed no crime, or we might say that they have committed a crime, but we excuse it in this situation. Either way, the defense operates to prevent the criminal conviction.

Formulations of the Insanity Defense

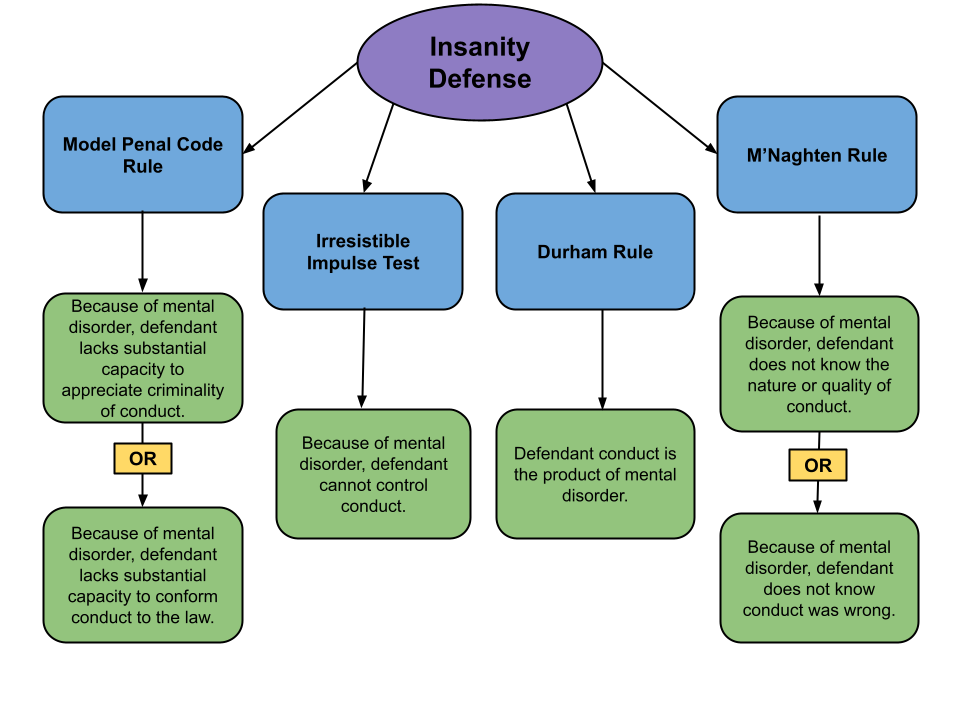

The idea of the insanity defense has long existed in the criminal common law, stemming from the notion that people should not be held criminally responsible for unintended actions or events that they could not control. The Constitution demands that a person be competent to stand trial (under Dusky), and that right is carefully guarded. However, there is no similarly protected “right” to assert an insanity defense. A few states have largely rejected the use of an insanity defense, and this has been found not to violate the U.S. Constitution (Kahler v. Kansas, 2020). Most states, however, do recognize the insanity defense in one or a combination of four basic formulations described in this section and pictured in figure 6.9.

The M’Naghten Rule

The first enduring version of the insanity defense originated in the mid-1800s in England. This version of the defense was a reaction to a high-profile case involving a man named Daniel M’Naghten. M’Naghten had murdered Edward Drummond, secretary to the prime minister of England, thinking that Drummond was actually the prime minister. M’Naghten wanted to kill the prime minister because he believed, under the influence of a paranoid delusion, that the prime minister was out to kill M’Naghten. M’Naghten was found not guilty of murder due to his mental illness and sent to a hospital under the common law approach to insanity at the time. However, many were upset by his acquittal, and as a result, a stricter rule was demanded and created: the M’Naghten rule (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, 2021).

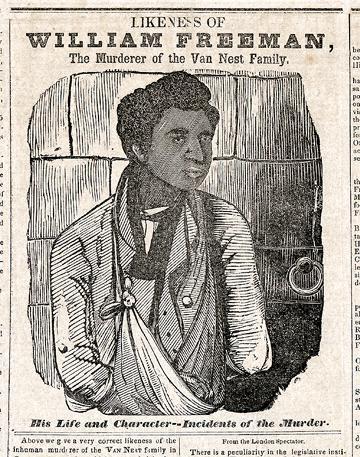

The insanity defense, and with it the M’Naghten rule, came to America just a few years later, in 1847, as part of the case of a Black and Indigenous man named William Freeman (figure 6.10).

Freeman had lived a difficult life, with signs of mental illness and a stint in prison, during which he sustained a serious head injury from beatings. After his release from prison, Freeman brutally murdered a family—both parents and a toddler. When his case went to trial, Freeman was defended in court by William Seward, former governor of New York and future senator and secretary of state under President Lincoln. Despite public hostility toward him for taking on this case, Seward was committed to seeking justice for Freeman. Seward attempted to defend his client based on insanity. However, the trial court declined to entertain the evidence and found Freeman guilty. Seward appealed Freeman’s case, and with arguments based in part on the recent English M’Naghten case, Seward won Freeman a new trial with the right to present evidence of insanity. Freeman died before his new trial, but the M’Naghten rule survived and became the American legal standard for insanity (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, 2021).

Under the M’Naghten rule, a defendant is presumed to be sane until they prove to the court or jury that, due to a mental disorder at the time of the act, they fit one or both of these criteria: (1) they did not know the “nature and quality of the act” they were doing, or (2) if they did know what they were doing, they did not know it was wrong. More simply, the M’Naghten rule is often described as requiring that a person did not know “right from wrong.”

For example, a person with a significant intellectual developmental disability kills someone by poisoning, but due to the influence of their mental disorder, they believe they have helpfully assisted the victim go to sleep by administering the poison. This scenario might support an insanity defense under the first M’Naghten prong: they did not understand the nature of their act. Alternatively, the defendant has knowingly killed the victim with poison, but they thought (due to a delusional disorder) they had to kill the victim to protect a child from certain death at the hands of the (actually innocent) victim. This second scenario might warrant a defense under M’Naghten’s second prong: they did not know what they were doing was wrong.

The M’Naghten rule is not perfect, and some of the later-developed versions of the insanity defense attempt to improve upon it. However, the M’Naghten rule became the standard definition of insanity in the United States, and it remains so in about half of the states and the federal courts (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, 2021).

The Irresistible Impulse Test

Under the irresistible impulse test, an accused person argues that a mental disorder prevented them from controlling their behavior or compelled them to do the bad act: they were unable to stop themselves. Therefore, they lack criminal responsibility for what is essentially an event outside their control. While the M’Naghten rule focuses on the accused person’s mental state, the irresistible impulse approach considers the person’s volition, or choice. Even when a person does understand their wrongful conduct, which would make them ineligible under M’Naghten, the irresistible impulse test asks whether the person was capable of controlling their conduct, given the impact of their mental disorder.

The irresistible impulse test is not so much a stand-alone legal standard as it is an addition to the M’Naghten rule, seeking to fill a perceived gap in coverage by M’Naghten. Many consider this test to be too broad, risking that a person with mere low self-control (rather than, say, a person with severe mania who is unable to control their conduct) could use the defense and avoid accountability (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, 2021). Indeed, much criminal conduct is committed on “impulse,” so the difficult question is whether that impulse was truly “irresistible” to the point that an insanity defense is appropriate.

Given its limitations, the irresistible impulse test is infrequently used. However, one sensational example of the irresistible impulse defense was the infamous case of Lorena Bobbitt. In 1993, Lorena Bobbitt cut off the penis of her then-husband John Wayne Bobbitt and disposed of it alongside a road, resulting in a dramatic trial and riveting multiyear international news cycle. At trial, Ms. Bobbitt’s defense argued that she was weakened by years of abuse and trauma at her husband’s hands, then became psychotic when he raped her that night. Her impulse to cut off his penis was “irresistible.” While prosecutors argued otherwise, Ms. Bobbitt’s team convinced the jury that she had acted under the force of an irresistible impulse—a theory that was permitted in her state—and she was found not guilty by reason of insanity (figure 6.11) (Sorrentino & Musselman, 2019).

The Durham Rule

Under the Durham rule of insanity, an accused person is not criminally responsible if their act was the “product” of a mental disorder. This “product” approach has been followed in New Hampshire since the late 1800s, but it got its name from a 1954 federal court case that used the same idea: Durham v. United States. The rule seems appealing in its simplicity, but it is not widely used and currently remains the law only in New Hampshire.

The Durham rule is so broad that it would seem to cover everything under the two previously discussed rules—M’Naghten and irresistible impulse—and more. It does not sit well with many observers that under the Durham rule, a person might understand what they are doing, know it is wrong, and be able to control their actions—yet still be excused from criminal responsibility upon the conclusion of a mental health provider that the person’s actions were otherwise a “product” of a mental disorder (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, 2021). According to critics, the Durham rule is also too dependent on the conclusions of mental health professionals—which can vary greatly from person to person (Sanabria, 2023).

The Model Penal Code Rule

Most states, including Oregon, have adopted portions of their criminal law from the Model Penal Code (MPC). The MPC is a criminal code created by the American Law Institute (ALI), a group of legal experts, in 1962. The MPC was developed to provide state lawmakers with standard language on which to base their statutes (figure 6.12). The MPC included a version of the insanity defense that is similar to the M’Naghten rule, with a touch of the irresistible impulse rule. This MPC version (MPC Section 4.01) provides that a person is not responsible for criminal conduct when, as a result of a “mental disease or defect,” they lack “substantial capacity” to either:

- “appreciate” the criminality of the conduct, or

- “conform” their conduct to the requirements of the law.

The MPC thus allows the insanity defense to be used where a person did not understand what they were doing, did not know that it was wrong, or was unable to stop their wrongful behavior (Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, 2021).

About 20 states use an MPC version of the insanity defense—just a few short of the number that use a variation on the M’Naghten rule (Strom, 2023). The federal courts initially adopted the MPC version as well. However, federal law was amended to restrict the use of the insanity defense in the 1980s. Public outcry demanded the defense be more restrictive after the acquittal of John Hinckley Jr., who shot then-President Ronald Reagan in an attempt to impress actress Jodie Foster. The Hinckley case is discussed in more detail in the Spotlight in this chapter.

Each state that uses the MPC version of the insanity defense has codified its own variation that can be used in the courts of that state. As an example, Oregon’s insanity defense tracks the language of the MPC but is alternatively titled “guilty except for insanity (GEI),” rather than the more typical “not guilty by reason of insanity” (Or. Rev. Stat. § 161.295). Additionally, in recent years Oregon rejected the outdated MPC language of “mental disease or defect” and substituted the term “qualifying mental disorder” as the precedent for a GEI verdict (Or. Rev. Stat. § 161.295).

Licenses and Attributions for Insanity as a Criminal Defense

Open Content, Original

“The Insanity Defense” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 6.9. Insanity Defense Diagram by C. Courtney and Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.10. Image of William Freeman in his jail cell in 1847, originally from the Rochester Daily Advertiser, is in the public domain.

Figure 6.11. Photo of kitchen knives by DDP on Unsplash.

Figure 6.12. Photo of law books by Nasser Eledroos on Unsplash.