6.5 Use of the Insanity Defense

The insanity defense is rarely presented in court, despite its intriguing nature, which brings it into media coverage as well as dinner-table discussions. The defense is even more rarely successful in excusing a person from criminal conduct. Any concern that offenders can easily “get away with” criminal conduct via the insanity defense is not well-founded. In fact, people who criminally offend are overwhelmingly convicted of those crimes and punished—and this is true even when mental disorders are part of the picture. In the federal criminal system, for example, more than 90% of charged defendants are convicted, almost all of them through guilty pleas without trial (Gramlich, 2019).

Only about one out of every 100 people being tried for felonies in U.S. courts asserts the insanity defense, and the defense is successful only about 25% of the time. In other words, in about 75% of the 1-in-100 cases where the defense is presented, the defense is rejected and the person is convicted (Justia, 2023). Even in the unusual event of having conduct excused due to insanity, rarely does that person walk away free. Long hospital stays and periods of supervision are the norm for those “excused” due to insanity.

As discussed earlier in this text, jails and prisons in the United States are filled with people experiencing mental illness and disability. While it is impossible to say how many were potentially eligible for an insanity defense, it seems reasonable to assume many were. For example, Oregon (which is certainly not alone in its mental health numbers) reports that in 2022 almost 30% of its adults in custody had serious mental disorders that needed high levels of care. At the same time, about 10% of Oregon adults in custody were rated to have “highest [mental health] treatment need,” and another 18.4% were classified with “severe mental health problems” (Oregon Department of Corrections, 2022). Where the issues were not raised at the time of conviction, it is impossible to know whether or how much of the conduct that landed these people in prison was a result of a mental disorder.

Prerequisites and Barriers to Defense of Insanity

The insanity defense is rarely successful because there are many barriers to its use, some of which are inherent to the system and others that are specific to certain defendants. A significant burden of proof is required of defendants who assert the defense, and that proof is both difficult to obtain and difficult to use successfully.

Proof of Insanity

The insanity defense is hard to prove. A successful insanity defense requires intricate proof on difficult issues of medicine and law. The insanity defense is generally an affirmative defense, meaning that it is a defense based on facts produced by the defendant, not by the state. Instead of the prosecutor having to prove that the person was “sane,” the accused person must offer proof that they were “insane,” or not mentally capable of committing a crime, according to rules in their jurisdiction.

The proof presented by the defense must include an evaluation by a mental health professional who can offer a diagnosis and explanation as to how a mental disorder impacted the conduct at issue. An evaluator would also consider whether the person is malingering, or “faking” a mental disorder to gain some benefit (discussed in Chapter 2). Remember that a diagnosis of a mental disorder is not the same thing as legal insanity. Many defendants who do have mental disorders, even significant ones, may be evaluated only to be advised that the evaluating expert does not believe that a mental disorder impacted their conduct sufficiently to warrant the use of the defense.

Additionally, not every diagnosed and impactful mental disorder can legally form the basis for an insanity defense. Non-qualifying mental disorders are diagnoses that, while potentially very impactful, do not make a person eligible for the insanity defense; if criminal conduct arises from a non-qualifying disorder, it will not be excused. Non-qualifying mental disorders usually include personality disorders, substance use disorders, and conditions such as pedophilia, which are generally excluded from the insanity defense by statute.

Diagnoses that are permitted to form the basis for an insanity defense are known as qualifying mental disorders. Qualifying mental disorders include psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, mood disorders such as bipolar disorder, trauma-related disorders, and cognitive disorders. Developmental disabilities can also underlie an insanity defense. Each of these disorders is discussed in detail in Chapter 2 of this text. In any case, the impact of a qualifying mental disorder must be so severe as to overcome a person’s ability to be criminally responsible for their behavior.

Defense Barriers

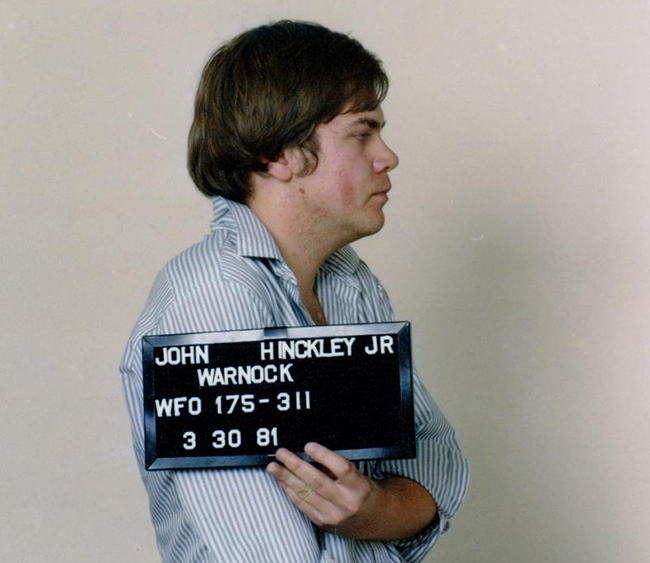

Another reason the insanity defense is not commonly used is that it is not necessarily the good “deal” some may imagine. Daniel M’Naghten, whose case inspired a tough new rule in his name, spent the rest of his life in a hospital, and John Hinckley Jr., who shot President Reagan in 1981 and inspired restrictive changes in the federal insanity defense, spent about 30 years in a state hospital and another decade on supervised release before being granted his freedom more than 40 years later in 2022 (Asokan, 2007; Johnson, 2021).

These cases are the rule, not the exception. A person who successfully asserts the insanity defense is almost certain to be committed to psychiatric care, often in a very restrictive setting such as a state hospital (figure 6.13). Furthermore, this commitment can be quite lengthy. Some states routinely commit patients to a state hospital for the maximum length of time they could be imprisoned if they had been found guilty (Oregon’s practice). Other states order commitment to care for an indeterminate period, with release nowhere in sight (McClelland, 2017). While early discharge is possible, it is not a certainty. This result may not appeal to every person to whom the defense is available.

Defendants may also hesitate to assert the insanity defense due to the stigma around mental health in our society generally or in their community specifically. Even if they do assert the defense, they may lack the prior diagnoses, history of treatment, and access to culturally competent assessments needed to gather the required proof. This is especially a problem for defendants who are Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC). It has become ever more apparent that the deck is fully stacked against BIPOC defendants with mental disorders, who suffer disproportionately from lack of access to care, lack of appropriate providers, and rampant misdiagnoses that may make mounting a compelling insanity defense near impossible (Perzichilli, 2020).

Prosecution Barriers

Even when a motivated, well-prepared, and racially/financially/medically privileged defendant does pursue an insanity defense, the prosecution will, in our adversarial system, appropriately challenge the defense, perhaps with a competing evaluation or other evidence. Elected prosecutors, who are overwhelmingly white (95%) and male (73%), are also undoubtedly impacted by their own biases—in addition to the directives of their role—when deciding when and to what extent they will challenge an insanity defense (Reflective Democracy Campaign, 2019). A prosecutor’s job, after all, is to convict offenders and protect communities, and supporting the use of an excuse defense like insanity can seem at odds with these concerns.

Excusing guilt due to the presence of a mental disorder meets the demand for fairness in the criminal justice system—that is, not convicting a person of a crime they did not intend to commit. However, it can also be very difficult and unsatisfying for victims. The insanity defense may be offered to excuse horrific and frightening offenses, including sexual assaults or brutal murders. Victims may feel justice is not served when no sentence or punishment is imposed—and these valid feelings may persist strongly even while they appreciate the injustice of punishing a person excused under the defense. The observing (and voting) public is likely to align with victims in their attitudes toward the insanity defense, which tend to be heavily negative. The overwhelming public perception is that the insanity defense is overused (it is not), and there is a general belief that verdicts based upon it fail to keep the public safe, though there is little evidence to support that belief (Hans, 1986).

Systemic Bias

Doubtless, the racism, sexism, and other improper biases inherent in all of our government systems, particularly in the criminal justice system, play a repeating role in the outcome of insanity defense cases. In some cases, statistics are available to illuminate this problem. For example, while juries and judges may be reluctant to excuse defendants who have done something harmful, studies suggest juries are more reluctant in the case of Black defendants (Maeder et al., 2020). It is reasonable to conclude that similar bias exists amongst prosecutors, judges, and other decision-makers in the criminal justice system. Bias likely impacts many mental health professionals conducting evaluations, defense attorneys who seek them, and every other cog in the wheel of the justice system. Because their behind-the-scenes work is less measurable than that of jury decisions, it is harder to produce supporting statistics as to some of these elements.

The result is that the insanity defense is far more likely to impact the verdicts of white men than other defendants. In Oregon, for example, of the approximately 600 people being supervised under GEI verdicts as of 2021, 82% were white and 83% were male. Only about 6% were Black, another 6% were Hispanic, and less than 3% were Native American (State of Oregon, 2021). This contrasts with Oregon’s jail and prison population, which around the same time was about 9% Black, 13% Latinx, and only 74% white (Vera Institute of Justice, 2019). The disparity in these numbers raises the question of why Black and Latinx defendants do not, apparently, assert or succeed in using the insanity defense at the same rate as white defendants. Although the barriers to the use of the defense are substantial for all, they appear to be more substantial for people of color.

SPOTLIGHT: John Hinckley Jr. and the Insanity Defense

John Hinckley Jr. was raised in a home not unlike that of many conservative American families. His father worked full time, and his mother stayed home to care for her son and keep up the house. Hinckley was emotionally dependent upon his mother throughout his adolescence, but no one would ever have guessed that he would someday become notorious for an attempted presidential assassination.

The first signs of trouble came in the late 1970s when Hinckley first viewed the movie Taxi Driver. What began as a simple affinity for the film later became an all-consuming obsession. He adopted the dress, mannerisms, and lifestyle of the main character, and he developed a burning desire for the actress, Jodie Foster, who depicted a child sex worker in the film.

This obsession manifested itself outwardly in the form of stalking. As his mental health deteriorated and Jodie Foster remained unimpressed by his attempts to get her attention, Hinckley concluded that he needed to assassinate the president of the United States. By the time he acted on this decision, Ronald Reagan was the sitting president. Hinckley made his attempt on March 30, 1981, and was promptly taken into custody (figure 6.14).

John Hinckley was tried in federal court in 1982, and many Americans were outraged when he was found not guilty by reason of insanity. An ABC News poll conducted the day after the verdict was read indicated that 83% of respondents believed “justice was not done” and Hinckley should have been found guilty of a crime. This public pressure spurred Congress—and many individual states—to enact major changes to the defense, all of which further limited defendants’ access to the insanity defense in criminal trials (Collins, et al., n.d.).

As for Hickley, he was transferred to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington. He was released back into the community in July 2016 after 41 years hospitalized under the supervision of mental health professionals.

Licenses and Attributions for Use of the Insanity Defense

Open Content, Original

“Use of the Insanity Defense” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: John Hinckley Jr. and the Insanity Defense” by Monica McKirdy, revised by Anne Nichol, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.13. Photo of Judge signing papers by Katrin Bolovtsova from Pexels used under the Pexels license.

Figure 6.14. Photograph of John Hinckley is in the public domain.