7.2 Custodial Environments for People with Mental Disorders

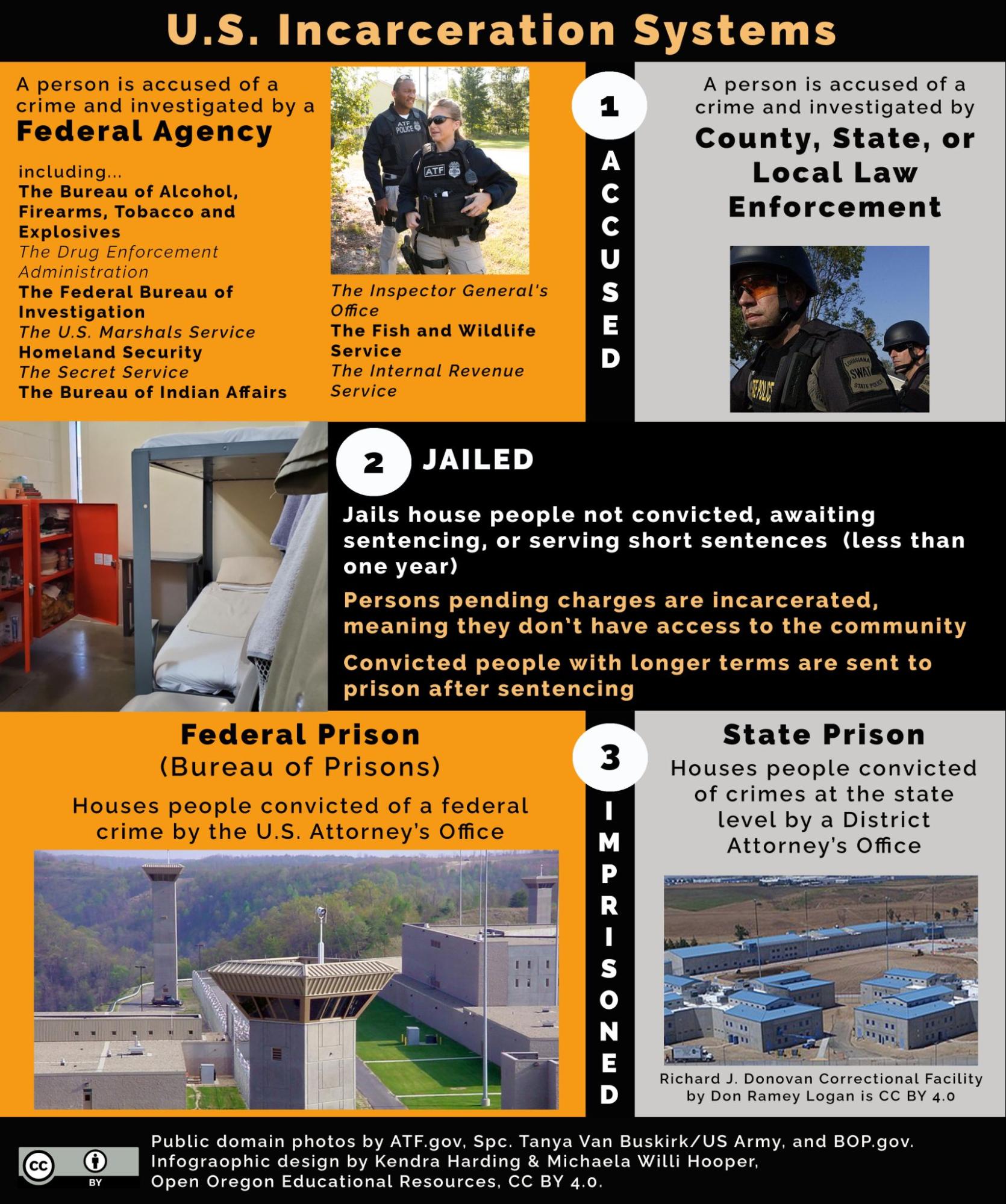

Because so many people in our jails and prisons have mental disorders—upwards of 40% by some estimates and even higher by others—all custodial environments are places where people with mental disorders may be incarcerated. The image in figure 7.2 highlights the major components of corrections in the United States. The criminal justice system is divided into state and federal systems at the law enforcement level. Federal officials enforce federal laws, and state or local officials (e.g., police, sheriffs) enforce state or local laws. State law violations are referred to local prosecuting attorneys and handled in state courts, while federal crimes are referred to federal prosecutors working in federal courts. Pre-trial detention and short terms of punishment are typically carried out within the system (state or federal) where a person is charged with a crime. If a lengthy sentence is imposed after conviction, the person will be transferred to prison in the system in which they were charged.

State and federal correctional facilities vary in their physical setups, policies, and practices. All of this impacts the experience a person with a mental disorder will have in that custodial environment. Federal constitutional standards, discussed later in this chapter, set a “floor” for the treatment of incarcerated people. These standards are met, or not, to varying degrees in different jurisdictions and facilities. Along with varying practices, jails and prison systems employ a range of terminology to describe what they do. One example is the practice of isolating an incarcerated person in a cell for most of every day. There can be great variability in how (and why) isolation is used, and the practice has different names, for example, solitary confinement, segregation, or use of restricted housing. Solitary confinement as a particular problem for people with mental disorders is discussed later in this chapter.

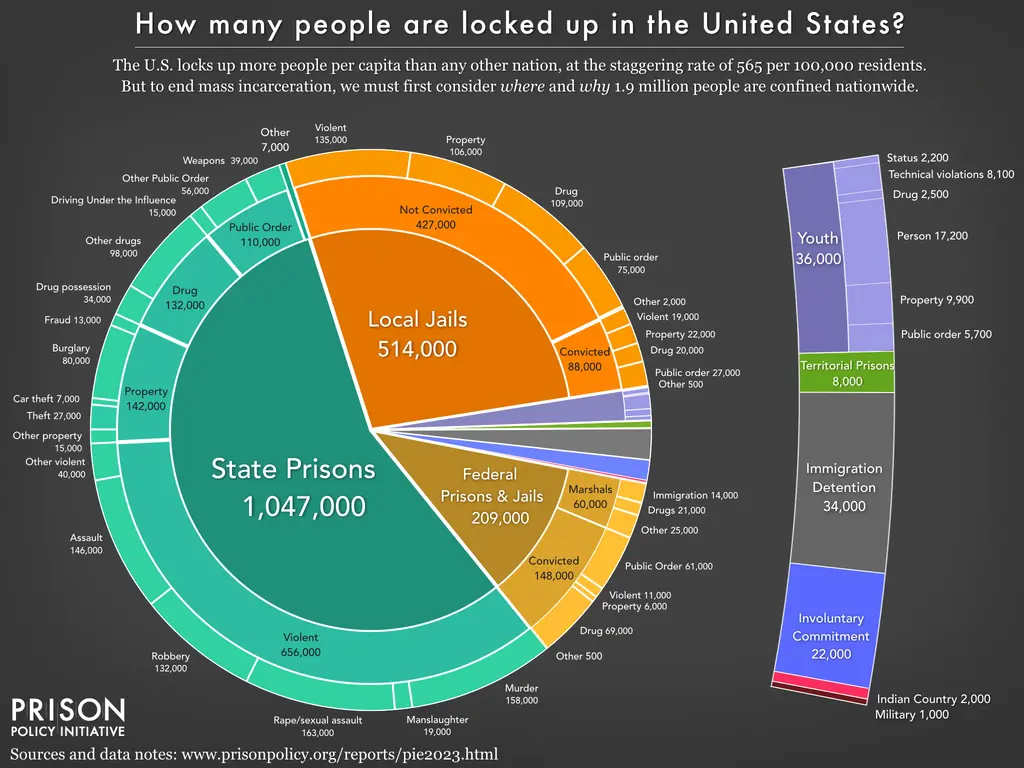

Note that the vast majority of people who are incarcerated in the United States are held in local jails and state prisons rather than in federal facilities (see figure 7.3 to compare these numbers). However, data are often more available from the federal system than from individual state, county, and local facilities, and that information is useful to our discussion in this text.

Incarceration in Jail

In the United States, almost 2 million people are currently incarcerated. As shown in the chart in figure 7.3, just over half a million of these people are held in local jails. While that is a huge number of people, that is merely the number in jail at any given moment. The people who make up that population are in constant flux; the average person will be in jail for just a few weeks before they are released or transferred (Prison Policy Initiative, n.d.). More than 10 million people are booked into jails each year, 80% of whom are charged with low-level and non-violent misdemeanors. Only 5% of people booked into jails are charged with violent offenses (Dholakia, 2023).

Although we often hear about people in “jails and prisons,” the reality is that these are two very different placements in many ways. As noted, the jail population is a short-term one, and most residents are legally innocent—they have been arrested and charged with, but not convicted of a crime. A majority of the jail population remains incarcerated due to the inability to post bail pending resolution of their charges. This means that the jail population skews heavily toward people who are poor and unhoused, a demographic with high rates of mental disorders (estimated at around 75%) (James & Glaze, 2006; Gutwinski, et al., 2021). In Atlanta, for example, unhoused people make up less than one-half percent of the overall population, yet they comprise 12.5% of the bookings into the city jail (Harrell & Nam-Sonenstein, 2023). About 44% of people in jail have mental disorders—a higher number than in prisons (37%)—again in part because this group is less likely to make bail than people without mental disorders (National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI], 2023; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2023). People of color (especially Black and Indigenous people) are significantly overrepresented in jails across the country. Black people are overwhelmingly more likely than white people to be sent to jail for pre-trial detention and to have an unaffordable bail set—compounding the impact of other factors, such as mental illness or poverty (Pew Charitable Trust, 2023; Dholakia, 2023; Sawyer, 2019).

Given the relative lack of power and visibility of most jail inhabitants, there is an enormous need for advocacy on their behalf. The Amplifying Voices of Individuals with Disabilities (AVID) Jail and AVID Prison Projects, both carried out by Disability Rights Washington, are advocacy efforts for incarcerated people who experience disabilities, primarily mental disorders. The attorneys who staffed the AVID Jail Project advocate for their clients in jails in Washington state and document the particular struggles of people with mental disorders in jail environments (Disability Rights Washington, 2016). Several AVID videos are linked in this chapter to allow students to hear directly from impacted groups about their experience in custody.

Watch the videos from the AVID Jail Project in figures 7.4 and 7.5, and consider how the speakers’ mental disorders and the jails’ response (or lack of response) to their needs shaped each person’s jail experience. What changes might have reshaped these experiences and led to different outcomes?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_Zs9Ma2PnQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MYZW7Pfz7S0

If you are interested in the AVID Jail Project, consider learning more and watching additional videos at the AVID Jail Project [Website].

Incarceration in Prison

While jails are short-term facilities, prisons hold people convicted of crimes who are serving longer-term sentences. Prisons are more apt than jails to determine that a person has a mental disorder and make placement or housing decisions based on that information. In prison, programming—education, life-skills training, and substance use treatment—can be provided for people who will spend years at the facility. Additionally, time and attention can be given to preparing people for eventual reentry into the community after prison. While these things are possible in prison, there is variation in facilities’ use of these opportunities.

Sedlis Dowdy, introduced at the beginning of this chapter, served 14 years in prison before being released to a psychiatric hospital where he spent 2 additional years. A friend recalls her optimism when Dowdy was finally freed for the first time in 16 years and placed into transitional housing. However, just 1 day after his release, Dowdy stabbed a man. He was sentenced to 8 more years in prison (Rodriguez, 2015). Watch the 3-minute video in figure 7.6, where Dowdy describes and compares his experiences in jail and prison, as well as in the community. Consider how the described incarceration of people like Dowdy serves, and fails to serve, the interests of community and individual safety.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oE2PDvHAzyc

Like jails, prisons accept anyone placed into their custody, including people with serious, even debilitating, mental disorders. Prisons are expected and required to keep all incarcerated people safe in long-term settings, which is not always an easy proposition. Ideally, prisons meet this demand by housing incarcerated people in environments that balance the need for immediate safety with the need for treatment, socialization, and other resources aimed at rehabilitation. Most people who experience mental disorders in prison are housed in the same places and ways as other incarcerated people, which is in keeping with the appropriate goal of housing people in the least restrictive environment where they can succeed. However, some incarcerated people are better served in a more specialized environment, despite the additional restrictions that may entail.

The Oregon state prison system, for example, has several levels of care and housing for people with mental disorders. The highest level—called a mental health infirmary—provides the most intensive care in Oregon prisons and is correspondingly quite restrictive. A person in this level of care would be closely supervised, which can be limiting as well as supportive. An incarcerated person with known, serious psychiatric needs might start in the infirmary level of care, with the potential to move on when they can be successful at a lower level of supervision. Oregon’s highest level of psychiatric care is available at only one high-security facility (figure 7.7) (Or. Admin. R. 291-048-0200 et seq).

Other Oregon prison facilities, however, offer lower and less-restrictive levels of care for people with mental disorders. At lower levels of care, people in custody may have access to ongoing support related to mental disorders, while being integrated with the general prison population. (Or. Admin. R. 291-048-0200 et seq.; Townsend, 2021). A wider range of placements for people at lower levels of care allows incarcerated people to receive care for mental disorders as well as access other therapeutic programs, or potentially be placed in facilities that are closer to their home communities.

Licenses and Attributions for Custodial Environments for People with Mental Disorders

Open Content, Original

“Custodial Environments for People with Mental Disorders” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 7.2. “U.S. Incarceration Infographic” by Kendra Harding and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Images: “CDCR – Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility by Don Ramey Logan” by Don Ramey Logan is licensed under CC BY 4.0; “Special Agents” by Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, “Louisiana State Police SWAT Team” by Spc. Tanya van Buskirk/U.S. Army, and photos from “Inmate Admission & Orientation Handbook” and “USP Big Sandy” by the Federal Bureau of Prisons are in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 7.3. How many people are locked up in the United States © The Prison Policy Initiative. All Rights Reserved, included with permission.

Figure 7.4. Siyad | AVID Jail Project by Rooted in Rights is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.5. Tallon | AVID Jail Project by Rooted in Rights is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.6. Living With Schizophrenia, in Prison and Out by WNYC is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.7. Oregon State Penitentiary by Katherine H is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.