7.5 Legal Right to Care in Custody

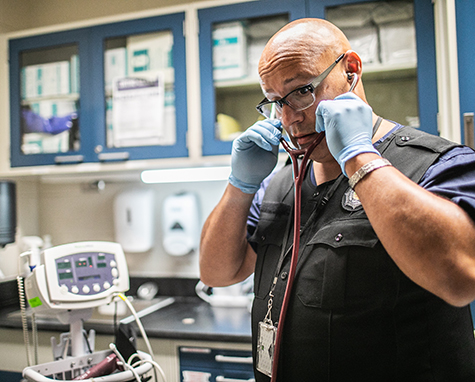

Given the enormous number of people with mental disorders who are confined in our nation’s jails and prisons, there is a significant, complex, and continuous need for support and care related to those mental disorders (figure 7.15). This section provides introductory information about the law governing incarcerated peoples’ access to and control over their mental health care. Legal rulings related to care for incarcerated people outline the extent to which the government is obligated to provide medical care, including mental health care, to incarcerated people and whether people in prison have autonomy with respect to their mental health care.

Courts have decided these issues based on the Constitution, specifically the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment,” and the “due process” clauses of the Fifth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which require fair procedures and treatment when important decisions are made impacting people in the criminal justice system. The concept of due process is discussed more in Chapter 6 of this text. While the federal government and all states must follow the directives of the U.S. Constitution as a minimum standard, be aware that some state laws may place additional or higher demands on their own facilities.

Eighth Amendment and Deliberate Indifference

One of the most important and often-cited cases related to health care in prison is that of Estelle v. Gamble (1976). In November 1973, Texas inmate J.W. Gamble sustained a back injury when a hay bale fell on him while he was working his prison job. Gamble complained of excruciating pain and later developed secondary health problems related to his heart. Gamble was seen by medical personnel who provided him with some care but did not resolve his pain. When Gamble was cleared to go back to work but refused, he was punished and placed in solitary confinement. Eventually, Gamble filed a lawsuit claiming that he had been subjected to “cruel and unusual punishment” in violation of the Eighth Amendment (Estelle v. Gamble, 1976).

The Supreme Court affirmed that the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment prohibited “unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain” and agreed that failure to provide medical care could, in some cases, rise to a level that would violate that directive (figure 7.16). The Supreme Court clarified, however, that only deliberate indifference by prison officials concerning providing medical care can be a constitutional violation. The standard of deliberate indifference, introduced in Chapter 3, is quite a difficult standard for plaintiffs to prove.

Proof of deliberate indifference requires showing that an official was aware of the concerns identified, yet chose not to take action to avoid harm. Accidental failures or poor judgment by a doctor or by the prison are not considered deliberate indifference, and thus they are not violations of the Constitution: “Medical malpractice does not become a constitutional violation merely because the victim is a prisoner” (Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. at 106). In Gamble’s case, doctors had seen Gamble repeatedly and tried to care for him. While that care was perhaps poor, it was not deliberately indifferent because it did not evidence callous disregard for Gamble’s well-being. In short, Gamble lost his case.

If a person who is incarcerated believes they have not been provided needed medical care, they can self-advocate or file an internal complaint, or, if certain conditions are met, they might be able to file a lawsuit—but they are unlikely to succeed in a lawsuit based on a constitutional claim. While Estelle v. Gamble does allow incarcerated people to sue based on failure to provide medical care, the deliberate indifference standard severely limits their ability to prevail. To hold a prison liable for failing to provide adequate care, an incarcerated plaintiff must be able to prove that the prison was aware of the need for care and consciously chose not to provide it.

Access to Mental Health Care

Another important case in discussions of prison care for mental disorders is Bowring v. Godwin (1978). While Bowring is not a Supreme Court case and technically governs only federal courts in certain areas, it represents the general agreement among federal courts that, like other medical care, mental health care must be provided to incarcerated people, and certain denials of care may violate the Constitution (A Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual, 2020).

In the Bowring case, plaintiff Larry Bowring had been convicted of multiple felonies and sentenced to prison time in Virginia. When he became eligible for parole, Bowring was denied release due to, among other reasons, the symptoms of his mental disorder that were deemed likely to make him unsuccessful on parole (Hoard, 1978). Bowring sued, asserting that the prison unconstitutionally failed to provide him with care to alleviate those symptoms and allow him to be considered for release. Ultimately, the Bowring court applied a similar standard as in the Estelle v. Gamble case, holding that incarcerated people are entitled to treatment for mental disorders, within reasonable bounds (figure 7.17). The court declined to “second guess” prison medical decisions, deferring to the expertise of medical professionals, but the court did say that prisons are required to provide care according to their judgment. Generally, only necessary and not overly burdensome mental health care is required, and failure to provide proper care does not violate the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution unless, as established in Estelle, the jail or prison officials act with deliberate indifference (A Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual, 2020).

Right to Refuse Care

An important aspect of medical care, including care for mental disorders, is making choices about that care, which may include refusing recommended care. The issue of whether and to what extent an incarcerated person can be forced to accept treatment for a mental disorder was addressed in the 1990 case of Washington v. Harper.

Walter Harper was incarcerated in a Washington state prison for many years on robbery charges. He had resided in a mental health unit for much of that time and had willingly taken medications to treat psychosis. However, when he stopped taking medications, Harper engaged in assaultive behavior that resulted in his transfer to a prison hospital setting. There, after a process involving the approval of multiple doctors and a finding that he was dangerous if not medicated, Harper was given antipsychotic medication against his will.

Harper sued, claiming that his due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment were violated when the prison forced medication on him without additional court proceedings. The Supreme Court considered the case and ruled that the Washington prison procedures were adequate to protect Harper’s rights and that the prison could administer involuntary medication using these procedures if their action was rationally related to a legitimate prison interest (e.g., maintaining safety and order). An incarcerated person with a mental disorder can refuse medication, but that can be overruled if the prison procedures determine that the person is dangerous without the medication and that giving the medication is in the person’s best medical interests (Washington v. Harper, 1990).

Under the Washington v. Harper case, incarcerated people who are seriously impacted by mental disorders such that they may harm themselves or others when unmedicated will have a difficult time refusing medications. Although the law may represent a reasonable balancing of diverse interests, the loss of autonomy for the incarcerated person can be very difficult. Forced medication can also bring other indignities, such as undesired side effects from the medication and facility hearings that violate the privacy of the incarcerated person. In contrast, prisons have a directive to maintain safety and order, as well as to treat people who may be too impaired to act in their own self-interest.

Watch the video in figure 7.18 for a discussion of the issues at stake in forcing medication in the jail setting: the due process rights of incarcerated people, the autonomy of an unconvicted person, and the desire to protect a person from psychiatric decompensation. These issues are often explored at extremely limited hearings that may not suit the gravity of the matter from the incarcerated person’s perspective.

Further information about the topic of prisoner lawsuits is beyond the scope of this text, but if you are interested in learning more, feel free to explore materials specifically addressing this topic such as the Columbia University Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual [Website].

SPOTLIGHT: Preventing Suicide in Jail

Among the most devastating outcomes of mental health problems are self-harm and suicide, which are significant threats to people in custody. This is especially true for certain more vulnerable groups (e.g., juveniles), but the risk spans all incarcerated populations, among which suicide rates are much higher than in the general population (National Institute of Corrections, n.d.). In February of 2024, the Federal Bureau of Prisons reported on all prison deaths in the federal system during the period from 2014 to 2021. The most frequent cause of death in prison was suicide, which accounted for more than half of the 344 total deaths during that period. Staffing deficiencies, inadequate assessments, and inappropriate mental health care assignments (e.g., failure to provide treatment or follow-up) were all identified as contributing factors to these deaths (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, 2024).

In a survey of state facilities done in 2019, the Department of Justice found that about a fifth of prisons and a tenth of local jails had at least one suicide that year. Suicide accounted for a startling 30% of deaths in local jails in 2019—representing a 13% increase from 2000 numbers (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 2021). The numbers also point to particular risks for certain groups: half of the people who died by suicide in local jails had been there for 7 or fewer days, and most of them were unconvicted and awaiting court proceedings (figure 7.19). The highest rates of suicide were among inmates aged 55 and older (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 2021).

How do we prevent these tragic deaths? Jails and prisons can, and must, do a better job of identifying those at risk and providing necessary supervision and care. One example of a jail taking an active role in suicide prevention is the Clackamas County Jail in Oregon. Take a look at the jail’s suicide prevention resources [Website], if you are interested. The jail emphasizes recognition of the problem (“The problem is real. Know the signs.”) and requests action from people in custody as well as from their loved ones (e.g., by contacting jail staff at a given phone number). The Clackamas County website acknowledges common barriers to taking action, including the idea that “someone else” will do something. The site also alerts readers to numerous suicide warning signs that should not be ignored (e.g., talking about death, withdrawing from friends, giving away possessions) (Clackamas County Sheriff, State of Oregon, n.d.).

For a comprehensive report on the problems of suicide and self-harm in custodial environments, including best practices for prevention, you may consider reviewing the Suicide Prevention Resource Guide: National Response Plan for Suicide Prevention in Corrections [Website] created by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. Although this additional reading is not required, you are encouraged to be aware of this resource and the risks it seeks to prevent. As stated in the introduction to the guide:

Suicide is a profoundly solitary act. The response to it, however, must not be. Suicide prevention requires a coordinated, multifaceted team effort. Nowhere is that more true than in jails and prisons.

Incarcerated men and women are a socially excluded population characterized by a multitude of personal and social problems and, often, mental health or substance abuse issues. Those risk factors for suicide are compounded by confinement, leaving some people feeling overwhelmed and hopeless. Tragically, too many of them die by suicide as a means of ending what feels like inescapable pain (Barboza, et al., 2019, p.4).

Licenses and Attributions for Legal Right to Care in Custody

Open Content, Original

“Legal Right to Care in Custody” by Monica McKirdy and Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Revised and expanded by Anne Nichol.

“SPOTLIGHT: Preventing Suicide in Jail” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 7.15. Medical provider at work in federal prison by U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.16. Doctors and patient in jail hospital, circa 1940 by King County is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 7.17. Photo by Siviwe Kapteyn is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 7.19. Photo by Aaron Robinson on Unsplash.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 7.18. Forced Medication Behind Bars by Rooted in Rights is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.