8.4 Achieving Success in Reentry

As discussed in Chapter 7, the process of reentry should begin while a person is still incarcerated. Assessment and planning within the facility should guide the person’s eventual transition out of custody, informing what the person needs to succeed in the community. This planning aspect of reentry will differ for a person incarcerated in a jail setting versus a prison setting. Jails, compared to prisons, have fewer opportunities for long-term reentry planning and smaller budgets for programming. While prisons, compared to jails, may have more resources for treatment programs and longer-term planning, there are downsides as well. For example, prisons are often located farther away from a person’s home community, making reentry connections more challenging (figure 8.6).

Planning that leads to appropriate support during reentry into the community reduces the risk of re-incarceration and other bad outcomes, including recurrence of symptoms of a mental disorder, drug overdose, and death by suicide. For people recently released from incarceration, all of these risks are very high. For example, one study found that the risk of death from overdose among formerly incarcerated people was 20.2 times higher than for the general population at 1 year post-release (Ranapurwala et al., 2018). People who are released from prison also have disproportionately high rates of death by suicide compared to the general population, especially during the first weeks following release. Rearrest rates are striking: about 43% of people released from state prisons are rearrested in the first year following their release (Antenangeli & Durose, 2021).

Responding to Risk and Needs

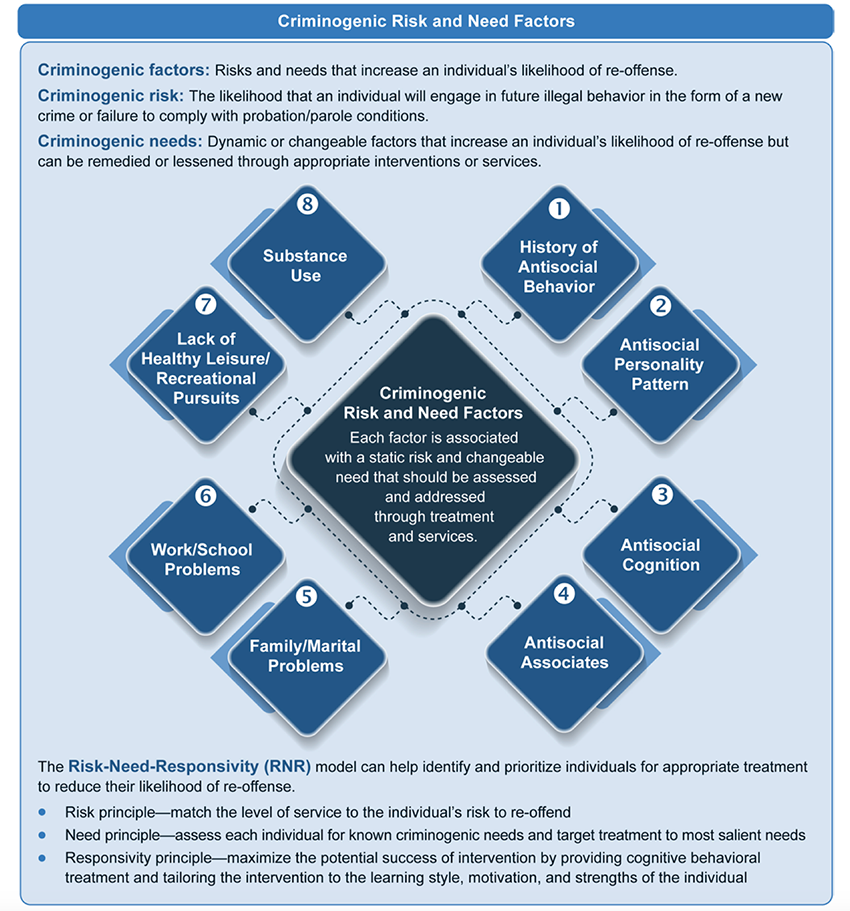

A key step in helping people succeed after incarceration is understanding their criminogenic risk, or risk of criminally reoffending. That information can be gathered in assessments and used to provide proper support; addressing the factors that impact the person’s likelihood of reoffending can reduce that risk and increase success. The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model is a set of principles that guides the process of identifying and prioritizing individuals for appropriate treatment.

The idea behind the RNR model is that assessment of risk and needs should be used to reduce criminal reoffending. This is done by assessing risk among a population and using that information to determine (1) who to help, (2) what help they need, and (3) how to provide that help. The RNR model suggests that people with a very high risk of reoffense should get the most support because there is the greatest opportunity to reduce recidivism when we treat those individuals. Treating this group represents the best use of limited resources. Conversely, people with a low risk of reoffense should get little or no treatment. This is an efficient allocation of resources and a recognition that when we over-resource low-risk people—or give people more help than they need—that does not boost their success.

The principles of the RNR model—risk, need, and responsivity—guide whether, how much, and how a person should be supported to reduce the risk of reoffending, based on that person’s characteristics (National Institute of Corrections, n.d.).

- The risk principle looks at who should receive treatment, based on their assessed criminogenic risk, or risk of reoffending (Lutz et al., 2022). Assessments look at specific risk factors (pictured in figure 8.7) that have been found to impact a person’s likelihood of reoffense. The risk principle generally dictates that people with higher risk of reoffending, based on assessments, should get more intensive support or intervention. People with low risk may need little or no support (National Institute of Corrections, n.d.).

- The need principle identifies what problems should be treated with specific services (Lutz et al., 2022). Identifying a person’s specific needs and targeting them can help reduce a person’s risk. Changeable risk factors are associated with “needs.” For example, substance abuse increases a person’s risk and represents a “need” because it can be targeted and potentially addressed with treatment (National Institute of Corrections, n.d.). Some needs, like serious mental illness, are not necessarily associated with the likelihood of criminal reoffending, so they are not considered criminogenic risks. However, these needs can be destabilizing, and they must be addressed for a person to benefit from other services (Lutz et al., 2022).

- The responsivity principle considers how we treat a person or what treatment should look like (Lutz et al., 2022). Responsivity requires that support be provided in a way that is effective for the person being helped. An intervention or support needs to be both generally effective and specifically adjusted to the identity or circumstances of the person being helped (e.g., culturally appropriate) (National Institute of Corrections, n.d..; Bonta & Andrews, 2022).

Additional Needs: Housing and Employment

Compared to the general public, formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be unhoused (The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2021). Although lack of housing is not considered one of the primary criminogenic risk factors for the RNR model, access to housing is critical to a person’s well-being, and there is some evidence that access to housing reduces recidivism (Jacobs & Gottlieb, 2020). However, people leaving criminal custody often do not have adequate housing support.

While housing support is lacking, there are plenty of barriers to obtaining housing. Some public housing programs, for example, exclude those with violent criminal records. Mental disorders are another barrier; people who experience these disorders are already at increased risk of being unhoused due to factors such as stigma (Coyne, 2021). The housing problem is further exacerbated for people of color in the reentry process, as racism reduces access to housing and increases the likelihood of a person living in an under-resourced community with higher homelessness rates overall. Furthermore, while people leaving incarceration are more likely to be unhoused, they are typically denied related government assistance if they have resided in an institution for more than 90 days. In these cases, the person must be out of jail or prison and unhoused for another year before qualifying as “chronically homeless” and becoming eligible for benefits (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2024).

The ability to find meaningful employment is another significant and well-established challenge for formerly incarcerated people. People who are employed are less likely to recidivate, but, problematically, rates of unemployment are much higher for formerly incarcerated people than for others (Couloute & Kopf, 2018). Even brief incarceration can lead to unemployment and impair future opportunities. Disclosure of a criminal justice record can negatively impact employer callbacks for job applications, making expungement an important avenue to increase employment opportunities for those with criminal records.

Notably, the challenge of employment, like that of housing, is often related to social factors that are not specific to the formerly incarcerated person. Best practices for reentry may be focused on offsetting some of these external barriers rather than treating anything specific in the individual. One way to do that is the development of employment-focused programs that are inclusive for people reentering the community from jail or prison.

SPOTLIGHT: Reentry Support Programs

Some reentry programs serve many roles for their clients, providing housing assistance, peer support, case management, and more. Others are more focused on a specific need, such as job support. This Spotlight shares just a few programs that attempt to meet the needs of people reentering the community post-incarceration. Consider researching reentry programs in your area that help people with and without mental disorders.

Homeboy Industries, located in Los Angeles, California, is the largest gang rehabilitation and reentry program in the world. This program offers a variety of reentry services, including tattoo removal, case management, substance use support, education services, and a variety of job training programs. Mental health programming includes a needed focus on trauma, according to a program director: “Many of our clients have complex, or developmental, trauma. In addition to experiencing childhood trauma, they have experienced multiple traumas, throughout their lives” (Homeboy Industries, 2022).

The idea of peer mentorship is built into the successful Homeboy Industries program. Take a look at the optional video in figure 8.8 for an introduction to several Homeboy “Navigators” who support incoming trainees at Homeboy. Consider as you watch, how does this role benefit newly released people, as well as the person offering support?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WXvr4HNq0_o

In the Portland, Oregon, area, SE Works is a program that connects many people to employment opportunities. The program’s NewStart Reentry Resource Center is meant to support people who have been released from Portland-area jails. Employment is a focus of SE Works, but navigators and case managers also provide program participants with resources for housing and family reunification, as well as treatment resources and disability services (SE Works: One-stop career center, 2016).

Consider visiting SE Works [Website], or take a look at this video about the program [Streaming Video] for more information.

Also in the greater Portland, Oregon, area is the Clackamas County Transition Center (figure 8.9), which opened in 2016 as the first facility of its kind in the state: an “all-in-one” service center for people leaving jail or prison and at risk of returning. The stated goal of the program is to “break patterns and change lives” (Clackamas County Sheriff, State of Oregon, 2024). Situated a short walk from the local jail, the center offers many of the supports discussed in this chapter that are vital to recently-released people: employment and housing assistance, peer mentorship, mental health assessments, and referrals to medication treatment for substance use disorders. Probation officers at the center also conduct “reach-ins” (discussed in this chapter) at the jail and local prisons to assess and plan for future clients even before they are released from custody (Clackamas County Sheriff, State of Oregon, 2024).

Licenses and Attributions for Achieving Success in Reentry

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Achieving Success in Reentry” is adapted from Best Practices for Successful Reentry From Criminal Justice Settings for People Living With Mental Health Conditions and/or Substance Use Disorders by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which is in the Public Domain. Modifications, by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include condensing, revising and expanding the content.

“Spotlight: Reentry Support Programs” by Kendra Harding and Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Revised and expanded by Anne Nichol.

Figure 8.6. Photo by CHUTTERSNAP is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 8.7. “Criminogenic Risk and Need Factors” by SAMHSA is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.8. “Behind the Tattoos – Episode 2: Navigators at Homeboy Industries” by Homeboy Industries is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 8.9. “Inside the Transition Center” by Clackamas County Sheriff’s Office is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.