9.2 Fundamentals of Civil Commitment

Civil commitment provides a way for the legal system to respond to a person who has become unsafe due to a mental disorder. Initiation of the civil commitment process allows a person to be transported to and/or held at a hospital for intervention. A completed civil commitment allows a court to order the person to receive long-term treatment for their mental disorder. A civil commitment order can, but does not always, require psychiatric hospitalization; some commitments can occur in the community.

A civil commitment does not involve punishing a person for doing something wrong (which makes it different from a criminal case), but it does involve supervising a person and limiting their freedom—even potentially confining them (which is, in some ways, like a criminal case). Because civil commitment is a significant infringement on the freedom of a person who may have done nothing wrong or criminal, it is important to be extremely cautious in its use. There are processes and procedures laid out in every state’s civil commitment laws to ensure that commitment is used properly and that freedom and autonomy are protected.

Although all states have involuntary commitment processes, civil commitments are very unusual. After a long history of forced confinement and mistreatment, people with mental disorders today are almost always treated on a voluntary basis. This includes people with serious mental illness, a group generally estimated to include less than 5% of the population. In 2015, an estimated 9 out of every 1,000 people with serious mental illness were involuntarily committed in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2019). Numbers in many states have fallen significantly since then, often due to a lack of capacity for treatment rather than a lack of need. In Oregon, for example, the Oregon State Hospital admitted only 15 civil commitment patients in 2023, compared to more than 1,000 people admitted in connection with criminal cases (Watson, 2024).

More commitments are initiated than are completed. Some people who find themselves facing civil commitment decide to consent to voluntary services, preferring that to being ordered into care (SAMHSA, 2019). Many others are found inappropriate for commitment at some time during the process (for example, if they do not present a danger to themselves or the community). Additionally, sometimes, though it would be difficult to quantify exactly how often this occurs, commitment is not even attempted for people who do need care. Reluctance to initiate civil commitment proceedings can be based on two accurate perceptions about the process: that commitment is very difficult to obtain and that there are few resources to treat these patients.

Civil Commitment Process Overview

The civil commitment process differs from state to state—and sometimes even county to county within a state—because each jurisdiction has its own involuntary commitment rules with unique language and procedures. Before the 1960s, when most civil commitment laws were developed, people with mental disorders tended to be confined or segregated as a matter of course, rather than based on strict legal standards. So it is important to note that civil commitment laws do permit court-ordered treatment, but they evolved as a protective limitation on the practice of forcing people with mental disorders into treatment and institutions (SAMHSA, 2019).

Some states, including Oregon, have separate but parallel commitment statutes, one addressing people with mental illness (Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 426.070 – .170) and another for people with intellectual or developmental disability (Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 427.215 -.306). These laws have differing specifics suited to the protection of the populations addressed. References to Oregon law in this chapter relate to civil commitment due to mental illness. Many of the specific Oregon terms and procedures mentioned in this section are defined in Oregon Administrative Rules (Or. Admin. R. 309-033-0200 et seq.).

The flowchart in figure 9.1 shows the general progression of the civil commitment process in Multnomah County, Oregon. It is just one example of commitment procedures. As you can see, the commitment process is first triggered by a concern about safety due to a mental disorder, indicated by the white circle in the upper left of the chart. If the person does not agree to treatment, then a care provider may issue a preliminary “hold,” which can be followed by an investigation, a hearing, and an involuntary commitment. The proceedings can terminate at several points prior to a finalized commitment, including with a decision by the person to accept treatment on a voluntary basis. Each part of the process shown in the flowchart is discussed in more detail in this section.

As illustrated in figure 9.1, the civil commitment process starts with a concern about the safety of a person with a mental disorder. There are generally two options to address this concern:

- The person may receive voluntary treatment.

- The person can be held, on an emergency basis, for a limited period based on state law.

If a person is held for a civil commitment, there must be an investigation into whether the person is unsafe due to a mental disorder. Depending on the outcome of the investigation:

- If the person is determined to be safe, they are released.

- If the person is determined to be unsafe and is still refusing voluntary treatment, a court hearing will be held to determine whether the person meets state law requirements for civil commitment (e.g., whether the person is imminently unsafe due to a mental disorder).

There are two possible outcomes from the hearing:

- The court finds that the person does not meet the legal criteria for commitment (they do not have a mental disorder, or they are not unsafe at the required level), and the person is released.

- The court determines the person meets the criteria (e.g., they have a mental disorder making them immediately unsafe), and the person is involuntarily committed for up to 180 days to be treated in a hospital, a community-based program, or some combination of these until the person is stabilized and legally discharged.

Emergency Hold

The civil commitment process often starts with an emergency hold, which allows a care provider to order that a person be kept under medical supervision. This type of restriction may also be called a hospital hold or just a hold. The hold keeps a person safe while providing time for their mental health to be assessed and for the next steps to be considered.

Often, however, a preliminary step is getting the person to a provider who can assess the person’s mental health. If a person is unwilling to go voluntarily, the law generally allows the person to be picked up by police (taken into custody) and transported to a hospital. This type of police custody is authorized for the limited purpose of getting the person to a hospital and is only allowable for the amount of time necessary to do so. Custody must be based on reliable information that the person needs to be controlled for safety reasons—that is, they are believed to have a mental disorder, and they are dangerous to others or themselves.

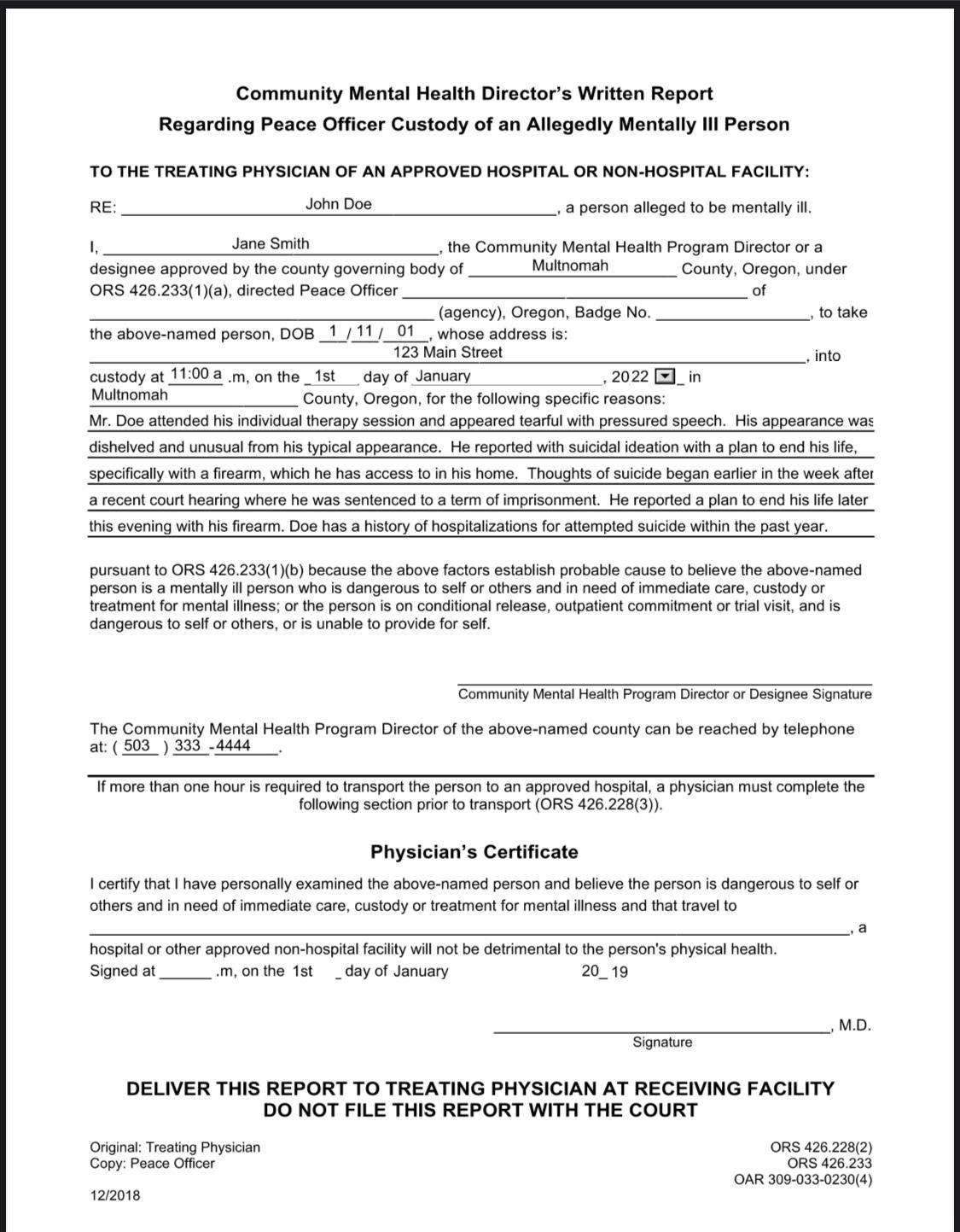

Custody can be initiated in various ways and is regulated by state law. In Oregon, every county has a mental health director who designates qualified mental health professionals with the power to approve hospital transport (figure 9.2). Police can also take a person into custody and to a hospital on their authority as peace officers.

Once a hold is initiated, its length is limited by state law. Most commonly, states permit involuntary treatment for just a few days before a judge must review the matter to ensure the hold is legally justified. In Oregon, for example, as shown in the flowchart in figure 9.1, a person may be held up to 5 business days on an emergency or hospital hold before the case must be reviewed by a judge.

A medical hold is only one route to initiating civil commitment. Most states allow other people, following certain rules and procedures, to initiate the process of civil commitment via paperwork submitted to a court. In Oregon, the law allows certain designated officials or any two people acting together (such as family or friends of the person) to initiate the commitment process.

Court Involvement

Regardless of how a civil commitment is initiated, the paperwork submitted to a court is what starts the legal process of civilly committing a person. In Oregon, the official paperwork submitted to a court is called a Notice of Mental Illness (NMI). The NMI is what triggers the court’s involvement in a legal commitment.

The next steps in the commitment process are a pre-commitment investigation and a civil commitment hearing. A pre-commitment investigation includes an evaluation by mental health professionals to determine what, if any, mental disorder the person is experiencing and how that mental disorder is currently impacting the person facing commitment. Designated investigators, usually state or county mental health professionals, gather evidence that may be presented in a later commitment hearing. The person facing commitment will also have an attorney at this point, and that attorney may conduct a fact-finding process as well. Investigators may speak with family members or other witnesses. The investigation is intended to establish whether the person’s current circumstances warrant civil commitment: Does the person have a mental disorder, and does that mental disorder make them dangerous? The question of “dangerousness” is central to the court’s ability to commit a person, and it is not an easy question to answer. Dangerousness is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Diversion from Commitment

Even when the first steps toward civil commitment have been taken—a hospital hold is in place, or a petition has been filed, or a hearing has commenced—the person may not ultimately be committed. A pre-commitment investigation, or simply time, may reveal that the person is safe or that the person does not have a mental disorder warranting commitment (e.g., they were intoxicated rather than mentally ill).

Alternatively, during the pre-commitment period, a person may be “diverted” into voluntary treatment—avoiding involuntary commitment by consenting to necessary care. Diversion in this context is used in the same sense that this text has previously discussed criminal diversions (see Chapter 4). Diversion allows a person to access services without the burden or stigma of a formal system determination against them. In other words, a person can get the benefit of treatment without a judge having to decide they are dangerous. When possible, Oregon law encourages diverting civil commitment subjects into voluntary intensive treatment for a 14-day period rather than finalizing commitment (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.237).

Diversion to voluntary treatment may be preferred over involuntary commitment for many reasons. Voluntary treatment is potentially more effective and less expensive than commitment. Voluntary treatment may be more available; in many states, there is a critical shortage of beds and facilities for people who are committed involuntarily. It may also be more attractive to the impacted person than a lengthy and restrictive commitment, which can last for many months.

Finally, although civil commitment does not create a criminal record, it does create a record with consequences. A person who has been civilly committed will face limitations of their right to possess firearms, for example (18 U.S.C. § 922[d][4], 2022). They may also be more readily committed in the future, should similar circumstances arise. Oregon law, for example, provides a special pathway for commitment when a person has had two previous commitments and is exhibiting the same symptoms that preceded the earlier commitments (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.005). A person who engages in voluntary treatment, even in a last-minute diversion from commitment, does not face these consequences.

Findings Required for Commitment

If a person who is the subject of commitment proceedings is not diverted into voluntary treatment or otherwise released from the process, the court will hold a commitment hearing. The commitment hearing usually occurs fairly quickly—ideally in a matter of days from the initial hold. The hearing is conducted by a judge or hearings officer who will assess the evidence to determine whether the information satisfies the requirements for a civil commitment. The hearing is an adversary process, where the person facing commitment may have an attorney to present their position, and the state also employs an attorney to advocate in favor of commitment. Witnesses, including pre-commitment investigators and mental health evaluators, will be allowed to testify or submit reports, and attorneys can ask them questions.

The evidence and questions at the commitment hearing are directed to the issues on which the court must make findings, typically, whether the person is:

- affected by a mental disorder, and if so,

- whether that renders them dangerous (or gravely disabled) so as to justify commitment.

The presence of a mental disorder is often not the primary issue. Professional evaluators will offer expert opinions as to whether a person has a mental disorder, or the person may well agree that they have a mental disorder. The second question, whether the person is a danger to themselves or others, is the much more difficult and contentious question. The way that a particular state or its courts define “dangerous” is critical to the court’s findings on this issue, and of course, states define this term in varying ways. For commitment to be ordered, a person’s risk has to fit within the definition of “dangerous” in that particular state.

Typically, “dangerous” has its commonly understood meaning—likely to cause harm—so that a person who is making serious threats against themselves or another person, or who seems poised to hurt themselves or another person, may be deemed “dangerous.” Courts have also interpreted “dangerous” to mean immediately or imminently dangerous—meaning dangerous now, not in the future.

Many states also have a commitment category for “grave disability.” Grave disability is a specialized term that usually means the person is unable to provide for their basic needs (food, shelter) such that they will experience harm in the very short term. For example, a person experiencing delusions or paranoia about food may be unable to eat. If the person develops malnutrition due to these symptoms of their mental illness, they may be considered gravely disabled by their mental illness. Some states have a “grave disability” standard for commitment without using those precise words. For example, Oregon allows the commitment of a person who is “unable to provide for basic personal needs” (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.005; SAMHSA, 2019).

Commitment and Treatment

If, at the conclusion of a commitment hearing, evidence shows that the person meets that state’s criteria for commitment, then the judge will order an involuntary commitment. A commitment usually lasts for several months, but it can be shortened if the person regains stability. The maximum time for a commitment in Oregon is 180 days, after which another hearing is required to continue involuntary treatment. This period is fairly typical among state laws.

The care provided to a person under a civil commitment may involve hospitalization or an outpatient treatment program. In some circumstances, psychiatric medications can be part of the treatment that is required for the committed person. The person may agree to accept necessary medications, or, with additional procedures, they may be medicated on an involuntary basis. A person can be medicated on an involuntary basis when there is “good cause” to do so. Good cause might be established when medication is necessary to deal with an emergency. More frequently, good cause is based on the person’s lack of capacity to make a reasonable decision about taking medication, requiring medical providers to decide for the person. In Oregon, involuntary medication is a multi-step process with at least two doctors involved, and there is a separate opportunity for legal review as well (Yost et al., 2012).

As shown in the flowchart in figure 9.1, Oregon provides opportunities for a person to improve and progress, even while they are civilly committed. The person may start treatment in a hospital setting and progress to a less-restrictive community setting. If a person makes significant progress and no longer meets the criteria for commitment, the person can transition to “voluntary” status, in which case they can choose to leave the hospital (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.300). Most states have similar, though not identical, options for resolving commitments.

Licenses and Attributions for Fundamentals of Civil Commitment

Open Content, Original

“Fundamentals of Civil Commitment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.1. Flowchart of Civil Commitment in Oregon by C. Courtney, H. Courtney, and Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Adapted from Multnomah County Commitment Services.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.2. Community Mental Health Director’s Hold Form by Oregon.gov is included under fair use. Form filled out by Kendra Harding.