9.4 Legal Limits on Civil Commitment

One of the more important cases that speaks to the issue of civil commitment, and more broadly to the humanity and rights of people with mental disorders, is O’Connor v. Donaldson, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1975. Kenneth Donaldson (figure 9.6) was committed to a state psychiatric hospital in Florida by his father in 1957. Donaldson was committed based on his diagnosis of schizophrenia and stayed in the Florida psychiatric hospital for over 15 years. During this time, Donaldson did not display dangerous behavior and received minimal treatment for his mental disorder. While he was hospitalized, Donaldson tried repeatedly but unsuccessfully to gain release into the care of friends who had offered to help him live in the community (O’Connor v. Donaldson, 1975).

Finally, Donaldson filed a lawsuit for his release against Florida authorities, including his attending physician at the hospital, Dr. O’Connor. Donaldson based his lawsuit on a federal civil rights statute. The statute Donaldson used (42 U.S.C. § 1983, referred to as Section 1983) allows individuals to sue state officials who have violated a person’s federal constitutional rights. Section 1983 was originally passed as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, because it was intended to allow Black Southerners to sue state officials (often police) who were infringing on federal rights, such as the right to vote. Section 1983 allowed these lawsuits to be heard in federal rather than state courts. Federal courts were expected to be more sympathetic to civil rights, and hopefully less overrun by Klan members, than state courts.

Section 1983 allowed Donaldson to ask for help in federal court. He asserted that the state officials in Florida (the employees at the state hospital) had taken away his constitutional right to liberty. Section 1983, although created in the days of Reconstruction, is still the most important way for a person to challenge a state government official of any type that has violated the person’s federal rights.

Donaldson’s federal lawsuit eventually made its way to the Supreme Court on appeal. In its decision, the Supreme Court made landmark statements that signaled a change in how people with mental disorders would be seen with respect to individual freedoms.

Justice Potter Stewart wrote for a unanimous court:

A finding of “mental illness” alone cannot justify a State’s locking a person up against his will and keeping him indefinitely in simple custodial confinement. Assuming that that term can be given a reasonably precise content and that the “mentally ill” can be identified with reasonable accuracy, there is still no constitutional basis for confining such persons involuntarily if they are dangerous to no one and can live safely in freedom.

May the State confine the mentally ill merely to ensure them a living standard superior to that they enjoy in the private community? That the State has a proper interest in providing care and assistance to the unfortunate goes without saying. But the mere presence of mental illness does not disqualify a person from preferring his home to the comforts of an institution.

May the State fence in the harmless mentally ill solely to save its citizens from exposure to those whose ways are different? One might as well ask if the State, to avoid public unease, could incarcerate all who are physically unattractive or socially eccentric. Mere public intolerance or animosity cannot constitutionally justify the deprivation of a person’s physical liberty.

In short, a State cannot constitutionally confine, without more, a nondangerous individual who is capable of surviving safely in freedom by himself or with the help of willing and responsible family members or friends (O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. at 575-76) (internal citations omitted).

It is the last paragraph of the quotation above that is most commonly cited as the holding, or ultimate decision, of the O’Connor case. However, the preceding paragraphs, with their grand and somewhat poetic language, are significant as well, entertaining arguments in favor of restricting a person like Donaldson—and finding them inadequate. The O’Connor court was, in contrast to all of history, proclaiming that the rights of this marginalized group of humans could not simply be erased in favor of a desire to “help” them or due to a preference to avoid them. The court’s findings acknowledged the condescension and stigma that played a prominent role in the treatment of people with mental disorders. The court then clarified that this intolerance does not justify confinement. Rather, there must be something “more,” as the court said, to justify confinement.

The Requirement of Danger

Because the Supreme Court specifically forbade confining a “nondangerous” person who is “capable of surviving” in the community, the O’Connor case is cited for the proposition that civil commitment—a restriction on liberty—must be limited to people who are dangerous, whether to others or themselves, such that they are incapable of surviving safely if free. Legislatures have included this dangerousness requirement in their statutes, and courts have tended to interpret danger to mean imminent danger—or dangerous right now, at the time of the hearing (SAMHSA, 2019). For example, even if evidence indicates the person has ceased taking prescribed medication, and they are going to decompensate and become dangerous in a few weeks, that is not likely sufficient for commitment in most jurisdictions. Is this requirement of danger, right now, too strict? Those who advocate for more liberal standards of commitment—desiring to offer involuntary treatment to a wider swath of patients—claim that O’Connor v. Donaldson does not exactly require dangerousness, nor immediacy of danger. In fact, as seen in the language quoted in this section, O’Connor forbids confinement of “nondangerous” people without “more,” and the court never defines that “more.” Could it be that “more” includes a serious need for treatment? Or something else?

The argument that danger is not required by O’Connor is appealing to those who want civil commitment to be more available. This perspective suggests that people need help before they become dangerous, and that help should be provided, even if the person lacks the clear-mindedness to choose that help. For example, involuntary commitment could be used to treat a person who suffers from a lack of insight as part of their mental disorder and does not appreciate that they need treatment or medications. This person could, it is imagined, be helped at the first signs of deterioration rather than waiting until they are deeply psychotic and requiring a lengthy period of restorative treatment, possibly after hurting someone (Bloom, 2006). Would this not be more efficient and more humane?

Setting aside the results for individuals, the general prospect of requiring danger to be present before mental health treatment can be provided has bigger-picture consequences. There is a powerful argument that the “dangerous” standard does not protect people with mental disorders but rather hurts them. The “dangerous” standard may force society to allow people with mental disorders to become dangerous—fulfilling the negative thinking and stigma around people with mental disorders—before providing desperately needed help. This creation of danger, when alternatives exist, needlessly strengthens the negative public perception of mental illness and disability by effectively tying these conditions to dangerousness (Gordon, 2016).

The “gravely disabled” standard (or its variations), used in many states and discussed earlier in this chapter, has been an attempt to broaden the net for civil commitments outside of “dangerousness.” The idea behind these broader standards is to allow the commitment of people who are experiencing severe deterioration and struggling to care for themselves before danger is truly upon them. However, the gravely disabled or basic needs standards have often been viewed as still requiring, ultimately, dangerousness to self. In fact, many of the states that use this standard specifically include an element of “danger” (by inaction) in the requirement. Some statutes (including Oregon’s) specify that the grave disability results in serious harm (Bloom et al., 2017). It is unclear to what extent “grave disability” without resulting “danger” would be permitted as a basis for commitment under O’Connor—but perhaps a future Supreme Court case will tell us (SAMHSA, 2019).

Clear and Convincing Proof

Knowing that a person must be proven “dangerous” in order to commit them, the question arises as to how much proof of dangerousness is required. In 1979, just a few years after O’Connor v. Donaldson, the Supreme Court decided the case of Addington v. Texas, which addressed this question of level of proof.

Like Kenneth Donaldson, Frank Addington had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, but unlike Donaldson, Addington was probably dangerous. Addington had been threatening his mother, and according to doctors, he experienced delusions and had behaved in a dangerous manner repeatedly. Based on this information, Addington was committed to the Austin State Hospital—formerly known as the Texas State Lunatic Asylum—for an indefinite period (Addington v. Texas, 1979) (figure 9.7).

Addington challenged his commitment in court, and the case went up on appeal. The issue was how much, or what level of, evidence should be required to support Addington’s commitment to the hospital. Opposing his commitment, Addington argued that the requirement should be a lot of evidence, or as much as would be required to convict a person of a crime. Predictably, the state argued that less evidence was required, as this was a civil rather than criminal case (Addington v. Texas, 1979).

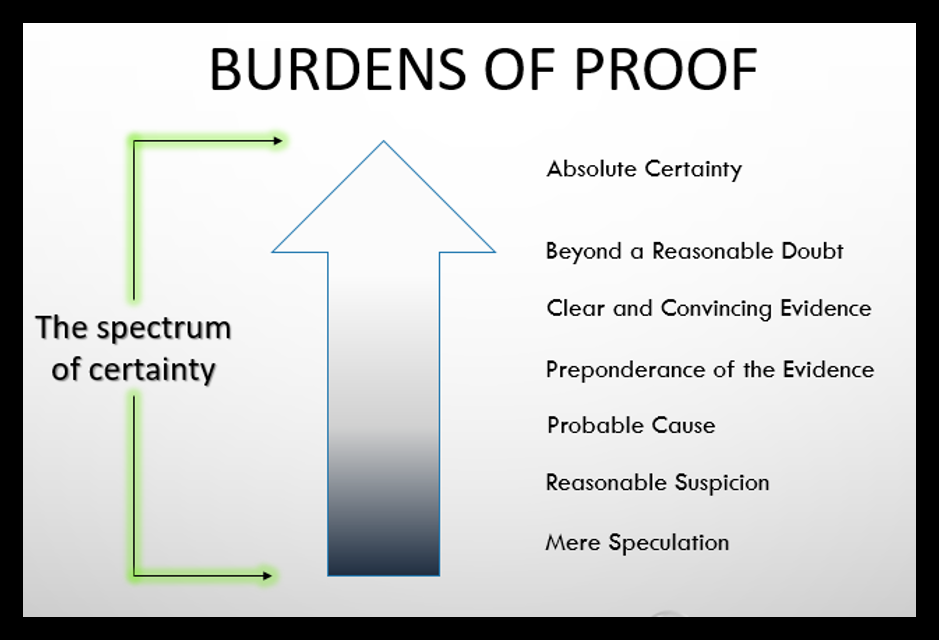

Typically, civil cases have a lower burden of proof, meaning the amount or level of evidence required to prevail, than do criminal cases. Civil cases are generally lawsuits between private parties, such as cases involving contracts or money disputes. These cases are typically won with a preponderance of the evidence (often characterized as just enough to tip the scales, or 51%). Criminal cases, in contrast, require proof beyond a reasonable doubt to convict a person. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is understood to mean overwhelming evidence that leaves no real doubt in the minds of decision-makers. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is not 100%, but it is somewhere close to that level (figure 9.8).

Although Addington argued that the state should be required to establish his suitability for involuntary commitment with proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” (the criminal standard), the Texas Supreme Court sided with the state and decided that a preponderance of the evidence (the civil standard) was sufficient for a civil commitment case. However, the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately disagreed with both parties, settling on a less common middle-ground standard: clear and convincing evidence.

As shown in the illustration in figure 9.8, the clear and convincing standard of proof is more demanding than the preponderance standard, but less stringent than proof beyond a reasonable doubt. The Supreme Court wrote that this in-between standard of clear and convincing evidence fit the circumstances of civil commitment, which is more weighty than a typical civil lawsuit, but not quite at the level of a criminal case. A court must weigh the “individual’s interest in not being involuntarily confined” against the “state’s interest in committing the emotionally disturbed [person].” The Supreme Court emphasized that commitment is “a significant deprivation of liberty,” and found it “indisputable” that commitment will “engender adverse social consequences to the individual,” namely “stigma” (Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. at 425-26).

Although the Addington court would not agree to require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, distinguishing civil commitment from criminal cases, the Supreme Court explained the need for at least the clear-and-convincing standard in the interest of fairness:

We conclude that the individual’s interest in the outcome of a civil commitment proceeding is of such weight and gravity that due process requires the state to justify confinement by proof more substantial than a mere preponderance of the evidence (Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. at 427).

Under the Addington ruling, if a court considering civil commitment found that witnesses and other evidence indicated a person was just slightly more likely to be dangerous than not dangerous, that person could not be committed (figure 9.9). The commitment judge would have to find that the person was far more likely to be dangerous than not dangerous—clearly and convincingly so. This is a significant burden not lightly undertaken and not easily met, especially in a matter as complex as presented by many mental disorders.

Like the O’Connor decision, the Addington decision serves as a limit on the use of civil commitment and a reminder of the seriousness of this measure. While it is not a criminal conviction, commitment does require very substantial (clear and convincing) proof of a very serious concern (danger) on a specific timeline (often “imminent”) before civil commitment can be used. In light of the historical disregard for the rights of people with mental disorders, this is reassuring. However, considering the need for protection and treatment of this vulnerable group, it is also potentially concerning.

Licenses and Attributions for Legal Limits on Civil Commitment

Open Content, Original

“Legal Limits on Civil Commitment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.7. Austin state hospital.jpg by Larry D. Moore is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.8. Burdens of Proof from Alaska Criminal Law – 2022 Edition by Robert Henderson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Figure 9.9. US Department of Justice Scales Of Justice.svg by Liquid is in the public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.6. Photograph of Kenneth Donaldson from Tampa Bay Times is included under fair use.