9.5 Commitments in Criminal Proceedings

In contrast to the purely civil commitments discussed in the preceding section, several forms of involuntary treatment occur in the context of criminal proceedings. These commitments are closely connected to an underlying criminal case, but the commitment is not a sentence or a punishment (although it may be perceived that way).

A person who is facing criminal charges may be committed for treatment in the following cases:

- When they are incompetent to resolve their criminal charges (either temporarily or permanently); or

- When they are found not responsible for criminal acts due to insanity, or in another phrasing, they are guilty except for insanity.

These situations pause or end the underlying criminal proceedings and give rise to the proceedings described in this section.

A less common type of commitment occurs after conviction and incarceration when a person convicted of a sex offense remains dangerous and faces continued confinement and treatment to manage that danger. Post-conviction commitments are discussed in the final section of this chapter.

Commitment to Restore Competence

State psychiatric hospitals across the country, including those in Oregon, are overflowing with committed patients. These are not patients who have been civilly committed due to danger—a group that, as discussed, is now relatively small. Rather, these patients were arrested and brought into the criminal system and then were committed to the hospital. Most often, these commitments are for the purpose of competency restoration, a process discussed in Chapter 6. A person who is incompetent, or unable to aid and assist, in their criminal defense must be restored to competence before resumption of their criminal case. In Oregon, this commitment and restoration process takes place pursuant to Oregon Revised Statute §161.370, and the commitments are commonly called “3-7-0” commitments.

Oregon is not alone in being overwhelmed with criminally incompetent patients, but it is a good example of the problem. The Oregon State Hospital’s daily average population of “aid and assist” patients has skyrocketed in recent years:

- In 2000, the hospital had a daily average of 74 aid and assist patients—just 9% of the total hospital population.

- In 2019, the hospital reported an average daily population of 260 aid and assist patients, over 40% of the hospital’s patients.

- In the spring of 2022, there were over 400 daily aid and assist patients, with waiting lists of people in jail needing to enter the hospital for restoration (Oregon Health Authority, 2019).

Although patients average fewer days in the hospital now than before, even a faster process cannot keep up with the demand for beds. As a result, there is a concern that people too mentally ill to resolve their criminal cases must remain in jail for lengthy periods, awaiting their (also lengthy) hospital commitment to undergo a process that will allow them to return to jail. Jail-based restoration, an option that eliminates the need for hospitalization, is being explored in some jurisdictions but thus far has not been done in Oregon. See Chapter 6 for more information on this option.

Advocates have pushed for faster hospital admissions for people facing competency issues, alleging that it is a violation of defendants’ civil rights to delay needed treatment. Complaints have pointed out the negative health consequences and equity issues associated with keeping very mentally ill people in jail with no treatment. In Oregon, a 2002 federal court order resulting from the lawsuit Oregon Advocacy Center v. Mink required that the state psychiatric hospital take no more than 7 days to admit patients who are unable to aid and assist in their criminal defense (Oregon Health Authority, n.d.). Other states have been similarly directed by courts facing this problem. However, compliance has been spotty over the years, with efforts hampered by shortages of mental health care professionals and a lack of beds in state hospitals.

Even while federal courts have demanded hospitals prioritize this set of patients, system observers and stakeholders have noted that other groups are suffering at the expense of this one. Only so many beds are available in a state hospital. Should some of them be reserved for the civil commitment patients you have just learned about—those who have committed no criminal offense? What about patients who have been found guilty except for insanity of serious crimes? Beds must be available to hold patients who have nowhere else to be safely held.

The reasons for the daunting number of competence commitments are numerous and complex. Among them is the lack of community mental health treatment access for people in need before criminal system involvement. Untreated, people with mental disorders are entering the criminal justice system in large numbers, as described in Chapter 4 of this text. Patients who are not competent to resolve their cases are a portion of that group.

Meanwhile, shortages of mental health professionals create barriers at all levels of care, including in hospitals and alternative community settings. This access issue, even at higher levels of care, exists in Oregon and other states, slowing patient progress through the system (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023; Zhu et al., 2022). As an example, in 2022, the Oregon State Hospital’s ongoing struggles with staff shortages required the closure of units and reduction of admissions (Loman, 2022).

Furthermore, despite efforts to move patients through the process quickly, restoration of competence is often a slow process. For example, there are limits on the treatment that can be provided to advance competence; it may be clear that psychiatric medications (figure 9.10) would benefit a patient, but if those are declined, there are limits on doctors’ ability to administer them involuntarily to make a person competent to stand trial (Sell v. United States, 2003).

Fortunately, perhaps, competency restoration efforts are not endless. In the face of hospital backlogs, courts have moved toward stricter limits on the time allowed to attempt competency restoration. For example, under previous rules in Oregon, restoration attempts could go on for years in a hospital setting. In August 2022, however, a federal court in Oregon set new, much shorter, time allowances for patient restoration at the Oregon State Hospital. Under these new rules, lower-level offenders being restored have to be released after no more than 90 days, and those who are charged with nonviolent felonies have to be released in 6 months (Oregon Health Authority, n.d.). Although this adjustment might reduce overcrowding at the hospital, new questions arise: where do these patients go upon release, and are they and their communities adequately served? In Oregon, negotiations and challenges around these limits are ongoing as of this writing, and similar conversations are occurring in other states.

Extremely Dangerous and Resistant to Treatment

Some patients, despite attempts at restoration, are found “never able” to aid and assist. That is, they are deemed permanently or indefinitely incompetent to resolve their criminal cases. At some point, prosecutors may be forced to dismiss charges (at least temporarily) against the person who is not or cannot be made competent to resolve those charges. This can be a terribly unsatisfying solution for the justice system and certainly for victims. It is a difficult situation for the accused person as well, who is left in a sort of limbo, unable to resolve their case with finality.

The Massachusetts case of Jose Veguilla, introduced in Chapter 6, is just such a case. Veguilla, his family, and his victim’s brokenhearted loved ones have watched his case churn in an endless cycle of evaluations and hearings that will never result in a finding of competence. “[E]very few months, the court convenes to discuss his case. A judge receives the update that Veguilla still has severe dementia and cannot proceed. And they agree to have the same hearing several months later. The hearing in January [2023] lasted less than 60 seconds” (Thompson, 2023, para. 44).

Oregon’s solution to cases like Veguilla’s was a statute, enacted several years ago, providing for the involuntary commitment of people who are deemed “Extremely Dangerous and Resistant to Treatment” (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.701-702). This statute is specifically targeted and used to manage people who have committed a most serious offense (e.g., murder) and who have an entrenched mental disorder that is not amenable or responsive to psychiatric treatment. In practice, this often involves people who are charged with a very violent offense but who simply cannot reach competence to resolve that charge.

The Oregon law first requires that the person be found “extremely dangerous,” criteria based on the offense they committed and the likelihood of repeated harm. The person must also be “resistant to treatment” (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.701). If restoration to competence was attempted and failed—and the person continues to exhibit those same challenges—that information would indicate resistance to treatment. If a person meets these qualifications, the Oregon law allows commitment to involuntary treatment for two years, with an option for recommitment. If the person stops qualifying for recommitment and becomes competent to proceed to trial, the prosecutor on the underlying case may reinstate criminal charges against the person (Or. Rev. Stat. § 426.702).

Oregon patients committed under the Extremely Dangerous and Resistant to Treatment statute continue to receive treatment for their underlying mental disorders—and, despite barriers, they are sometimes able to move out of the hospital and into less restrictive housing and treatment options. Patients committed under the statute are supervised by the Oregon Psychiatric Security Review Board, discussed in more detail in the next section.

Commitment After Insanity Defense

Competing for bed space at state hospitals are patients who have been committed for psychiatric treatment after successfully asserting the insanity defense in criminal court. These are patients who have been found not guilty by reason of insanity, or, as it is called in Oregon, guilty except for insanity (GEI). As you have learned, a successful insanity defense excuses a person from criminal responsibility for an offense based on the impact of a mental disorder. See Chapter 6 for a detailed discussion of the insanity defense. The excused person is not simply released as they would be with other “not guilty” verdicts; they are ordered into a term of treatment designated by law. This type of involuntary treatment after a criminal matter is sometimes referred to as a criminal commitment—as distinguished from the civil commitments discussed at the beginning of this chapter, which are unrelated to criminal charges.

Most people who are excused from criminal responsibility due to insanity are committed to a public psychiatric hospital, such as the Oregon State Hospital, for treatment and to ensure community safety (figure 9.11). The details of hospital treatment programs are beyond the scope of this text, but there are many opportunities and therapies available for different types of patients in various facilities. Programs will differ by jurisdiction. Feel free to click the link to learn more about the treatment programs at the Oregon State Hospital [Website].

Legal oversight of a person’s criminal commitment is generally managed by some combination of medical providers and legal personnel in the criminal justice system. In the federal system, for example, a criminally committed person is supervised by a probation officer, sometimes for life. A few states, including Oregon, have specialized systems to supervise people under criminal commitments. The Oregon Psychiatric Security Review Board (PSRB) is a somewhat unique oversight board composed of professionals from multiple relevant disciplines. The PSRB is charged with ensuring proper management and community safety for all Guilty Except for Insanity (GEI) patients, as well as the Extremely Dangerous and Resistant to Treatment patients discussed in the previous section. Board members include a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a criminal lawyer, a parole and probation officer, and a community member—each bringing different expertise and perspectives to their supervision duties.

To perform its duties, the PSRB holds public hearings where the supervised person is in attendance, represented by an attorney. The state, interested in public safety, is also represented by an attorney at PSRB hearings. Hearings may involve testimony from witnesses—primarily treatment providers—who advise the board of the person’s mental health status and treatment progress. Sometimes, hearings are an opportunity for the person and their treatment providers to request that a person be allowed conditional release from the hospital, meaning that the person is permitted to live in the community, often in a group setting, to participate in treatment under a set of rules and safeguards. If those conditions of release are violated, the person may be returned to the hospital. If you are interested, you may read more about Oregon’s PSRB here [Website].

Typically, people who have been criminally committed after an insanity verdict are ordered to remain under the supervision provided in their state for either an indefinite period or for the maximum length of time allowed by their underlying offense. However, if at some point it is determined that the person no longer meets the criteria for a criminal commitment—they no longer have a qualifying mental disorder or it no longer makes them dangerous to others—then the person must be released from supervision. Again, the standards for continued commitment and supervision in these circumstances will vary according to the law of the jurisdiction. However, note that the criminal commitment standard is different from that used to civilly commit a person, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Civil commitment can be based on a person’s danger to themselves. A criminal commitment typically requires that a person be seriously dangerous to other people.

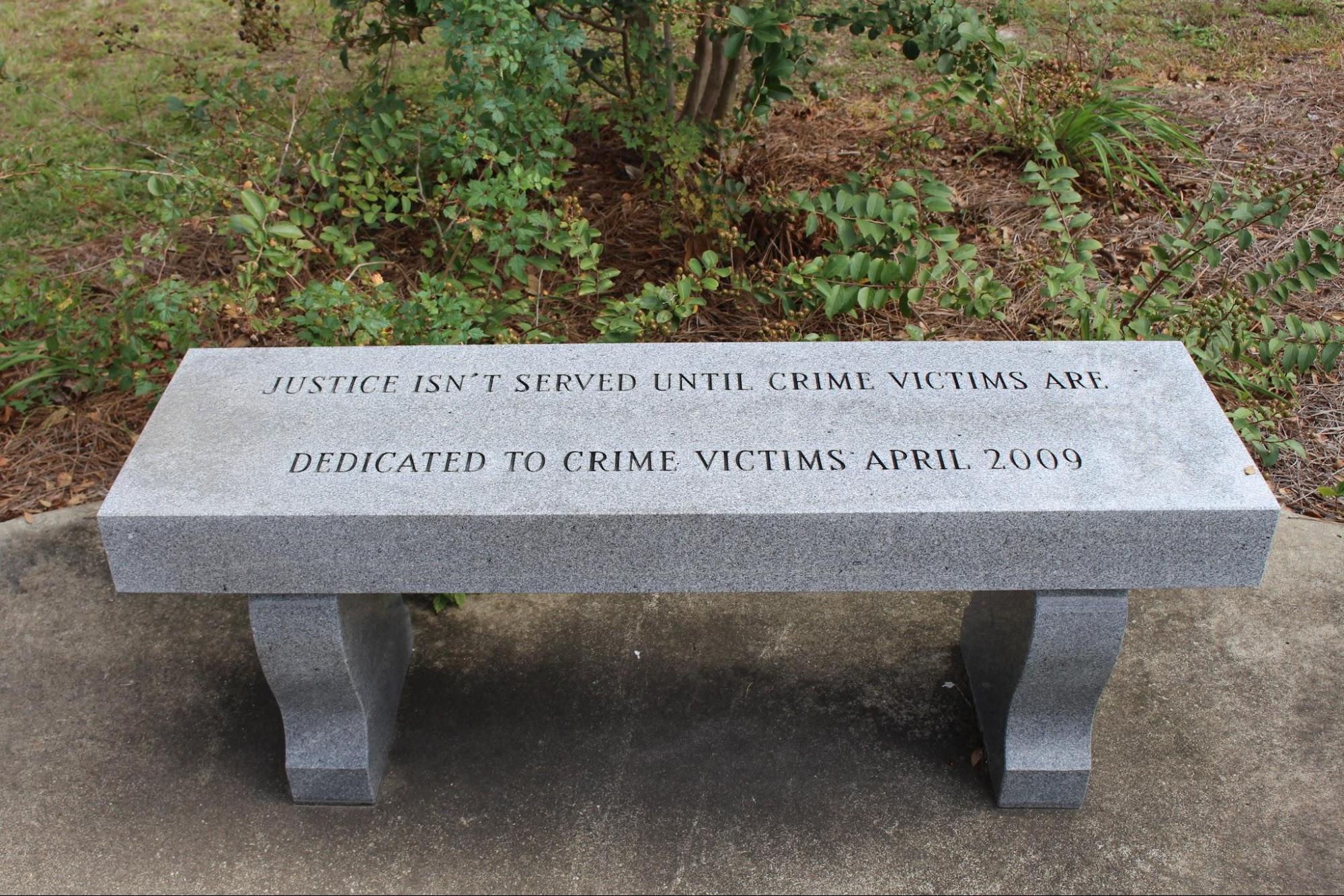

Regardless of how patients are managed or supervised in a particular state, their treatment can be a source of stress and concern to crime victims (figure 9.12) who may feel that justice was not served when the person with a mental disorder was “excused” from responsibility. There can also be an understandable sense of resentment toward patients who are able to access mental health care after committing serious offenses when other people who have not found their way into the criminal system may have very limited access to mental health care.

SPOTLIGHT: The Criminal Commitment of Andrea Yates

When a person with a serious mental disorder commits a terrible act that they certainly would not have done had they been well, the tragedy seems magnified, and the story of Andrea Yates fits that category. Yates’s story is a difficult one to read and absorb. It is an example of an act that would be a terrible crime, except for the presence of mental illness in the offender. Is this a case where you believe the insanity defense was appropriately applied? Was commitment to a hospital the right outcome in this case?

Andrea Yates (figure 9.13) began as a happy young wife. She and her husband wed in April 1993 and soon announced that they planned to have as many children as they could during Andrea’s reproductive years. It was after the birth of their fourth child that Andrea first showed signs of severe mental illness.

On June 16, 1999, Russell Yates found his wife shaking and chewing her fingers. She attempted suicide the following day and was prescribed antidepressants. Just weeks later, she again held a knife to her own throat and begged her husband to let her die. After this second suicide attempt, Andrea was hospitalized, diagnosed with postpartum psychosis, and prescribed several different medications that included antipsychotics. Andrea’s psychiatrist urged Andrea and Russell not to have any more children, but she was pregnant with the couple’s fifth child within 2 months of her diagnosis.

In November 2000, the fifth child was born. Andrea seemed stable for a few months until her father died in March 2001. This is when her psychosis returned in full force, leading Andrea to regularly mutilate herself. She became fully immersed in the Bible, her religious beliefs now becoming fixations. Between March and June of that year, she was hospitalized twice. After Andrea’s release in June 2001, her doctor told Andrea’s husband to monitor Andrea around the clock. Unfortunately, there was a 1-hour block of time on the morning of June 20 when Andrea was alone with her five children, during which time Andrea drowned each child, one by one. She then called 911 and her husband.

Andrea suffered from psychotic delusions. In her mind, she believed she was saving her children. She later reported to her prison psychiatrist that she believed her children were not righteous because she, herself, was evil. She believed that their souls could never be saved because of who she was, and killing them while they were young would be their only salvation.

Andrea’s first trial took place in 2002 and resulted in a guilty verdict with a sentence of life imprisonment. It was later discovered that a psychiatrist who had testified for the prosecution had given false testimony during the trial, and the conviction was overturned. A second trial in 2006 resulted in a not guilty by reason of insanity verdict. Andrea was committed to a psychiatric hospital where she remains to this day, refusing each year to seek release at her annual hearings.

Licenses and Attributions for Commitments in Criminal Proceedings

Open Content, Original

“Commitments in Criminal Proceedings” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: The Criminal Commitment of Andrea Yates” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.10. Image of medications by Qimono is licensed under the Pixabay License.

Figure 9.11. Photograph of Oregon State Hospital by Josh Partee is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.

Figure 9.12. Crime victims bench, Jesup.jpg by Michael Rivera is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, All Rights Reserved

Figure 9.13. Andrea Yates by Houston Police Department, Texas, is included under fair use.