1.2 What You Need to Know Before Reading This Book

As you read this book, you will absorb the information from your social location. Your social location is the culmination of cultural values and norms within a society. Culture affects personal and social development, and thus how people think and behave. Cultural characteristics that may influence your choices in life are age, gender, race, education, income, religion, sexuality, disability, and others. Our social location can influence our perspectives of others and how we respond to differences. Depending on your social location, you may have different emotional responses to this book, and you may bring your own experiences and stories regarding the topics we address. For most of this book, we focus on how race and ethnicity influence our perspectives and life outcomes.

The topics in this book evoke a range of emotional responses, as we will discuss harm, joy, discrimination, resilience, cruelty, hope, injustice, and more. For many of the cases or examples explored, police body camera footage, graphic court documents, and other explicit materials may be available; please take care when further researching these cases. The book project authors and leaders have chosen not to platform certain content to avoid further harming readers, particularly those who are members of marginalized communities. The materials that are shared in the book have been carefully selected to present the realities of our history and contemporary society, while also avoiding sensationalization or exploitation of those who have experienced atrocities. The ultimate goal is to ensure that the truth is neither softened nor obscured, but presented in a way that allows for meaningful understanding and empathy; your social location will likely impact how you make sense of what you read!

Please be aware that this textbook includes discussions and descriptions of various topics related to crime, criminal behavior, violence, and the criminal justice system that may be distressing or difficult to digest. Topics include, but are not limited to, physical and sexual abuse and sexual assault, domestic violence, homicide, substance abuse and addiction, exploitation, mental health issues, discrimination and inequality, and institutional misconduct and violence. The material presented is based on academic research, case studies, and real-world examples, providing a comprehensive understanding of race, ethnicity, and crime. If you find yourself in need of support while grappling with any of these subjects, here are some helpful national resources:

- National Domestic Violence Hotline: 800-799-7233 or thehotline.org

- Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN): 800-656-4673 or rainn.org

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): 800-662-4357 or samhsa.gov

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call or text 988 or 988lifeline.org

- The Trevor Project (hotline specifically for the LGBTQIA+ population): Call 866-488-7386 or text 678-678 or thetrevorproject.org

Relatedly, language is constantly changing and evolving. The authors acknowledge stigmatizing language throughout the chapters (for example, see Learn More in the next section or the discussion on the phrases criminal justice system vs. criminal legal system in Chapter 7). However, at times – for brevity, clarity in law, or consistency with cited research methodology – acronyms or terms such as “offender” and “victim” are used.

Finally, we cannot ignore the time at which this book is being published. The funding and the majority of this project’s work were completed before the Trump administration took office in January 2025. This book utilizes the language of diversity, equity, and inclusion of the era preceding this administration’s Executive Orders and whatever subsequent attempts to censor and suppress evidence-based education, student-centered pedagogy, and academic freedom persist throughout this administration’s tenure. The open nature of these materials permits adopters to continue to adapt the language necessary to preserve these approaches in the coming years. The status of research through a lens of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the field of criminology is yet to be determined, as well as the impact it will undoubtedly have on marginalized communities. This book project has been a collective effort by many authors, reviewers, and revisers of varying identities, life experiences, and academic backgrounds. At the time of this book’s publication, the future of diversity, equity, and inclusion in education is uncertain. Despite this context, we are moving forward based on the values and approaches represented in this section.

Nonetheless, we persist.

Learn More: Understanding Social Location, Voting Patterns, Elections, and Public Policy

One area of research interest for sociologists is the patterns and trends in voting. The United States prides itself on being a democratic society representing the people. In the United States, a principle of democracy is your right to vote in secret and choose the candidate you think is best. However, laws have intentionally excluded justice-impacted people from participating in our democracy. People of color are disproportionately impacted by policies that take away the right to vote after a conviction, referred to as felony disenfranchisement (Nellis, 2021). Over 2 million voting-eligible Black and Latinx Americans are blocked from participating in this fundamental right (Ghandnoosh, 2015). The Sentencing Project argues that we must restore voting rights for people with felony convictions to improve public safety (2023). Bozick, Steele, Davis, and Turner (2018) found that voting is among a range of prosocial behaviors in which justice-impacted persons can partake, similar to furthering education, associated with reduced criminal conduct. Hamilton-Smith and Vogel (2012) found that individuals with a history of criminal justice system involvement, having the right to vote, or the act of voting is related to reducing rates of repeat offending. Ultimately, voting makes people feel heard in the political process and helps develop a positive identity as a community member (Miller and Spillane, 2012).

Sociologists also look at who we vote for and how it is affected by our social backgrounds, location, personal beliefs, religion, and more. Race has historically impacted outcomes in presidential campaigns. Let’s consider the lead-up to the 2020 presidential campaign. President Donald Trump stoked racial strife and polarization during his presidency and campaign cycle. He made supportive comments about “white power” during the Charlottesville protests. The term “white power” is often used to reference or support the concept of white supremacy, which is the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and ethnicities, and is often used to justify poor or unequal treatment of other races and ethnicities. In his infamous tweets chastising protesters as thugs, blaming COVID-19 on China, or refusing to demand that the far-right Proud Boys “stand down,” he catered to the people who supported Donald Trump.

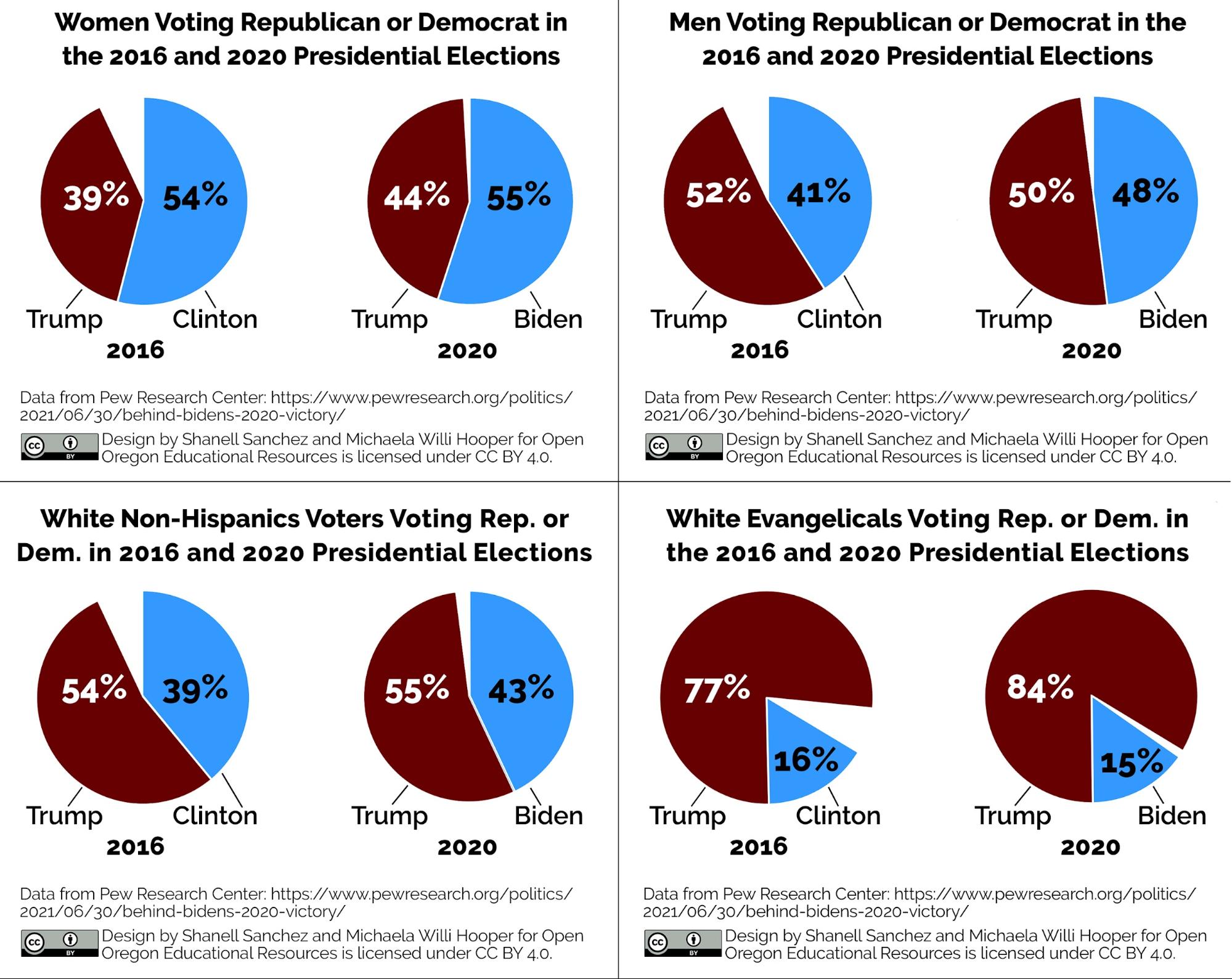

Trump’s base held more polar views from the rest of the nation, including more staunch opposition to immigration. In the 2020 election, Trump had unwavering support from white Evangelical voters (Gjelten, 2020). Ultimately, Joe Biden and running mate Kamala Harris, the first-ever woman of color on a major political party ticket, won the popular vote in 2020 (Sullivan and Agiesta, 2020). The overwhelming majority of people of color voted for the Biden-Harris ticket, including Latinx and Native American populations in Arizona. Voter turnout on Tribal land in Arizona surged compared with the 2016 presidential election, with some Tribes casting twice as many ballots as in the previous election (Fonseca and Kastanis, 2020; Vinopal, 2020). By contrast, the overwhelming majority of the white electorate voted for Trump, though a smaller percentage of white men voted for Trump in 2020 than in 2016. Similar to four years earlier, race, gender, and religion proved to be influential factors in voter tendencies in 2020.

Introduction

This book will take a sociological perspective on understanding race and crime. The social science researcher has the tools to answer questions about racial inequality in the criminal justice system. Sociology can expand the focus from the individual to examine broader structural forces. Sociology exposes the social dimensions of social problems and provides explanations of the prevalence of various types of crime, agencies, and programs designed to prevent and control crime and delinquency in a larger societal context. An abundance of research relates criminal justice to sociology. For example, sociologists examine the effects that race has on police stops and arrests. Kochel et al. (2011) found that when they controlled for suspect demeanor or how the suspect reacts to the officer, how severe the suspected offense is, presence of witnesses, evidence at the scene, and prior record of the suspect, people of color who were suspected of a crime had a 30 percent higher chance of being arrested than white suspects. Rojek et al. (2012) also found that in predominantly white neighborhoods in St. Louis, traffic stops are more likely to include a search in stops of Black drivers than of white drivers, especially by white police officers, controlling for characteristics of the officer, driver, and stop. The effect can work the other way too: In predominantly Black communities, stops by white officers are more likely to happen to people of color because white officers are racially profiling.

Sociologists also examine how people’s individual experiences impact others. The effects of mass incarceration in this country are felt by many more people than those convicted of crimes. It’s estimated that nearly half of all U.S. children have at least one parent with a criminal record, and the effects of incarceration can be felt for a long time (PBS, 2020). For example, research has found that parental incarceration can harm the whole family. Christopher Wildeman (2014) found that having a father go to prison increases the chance a child will become homeless, especially for Black children. Wildeman (2012) also found that mass incarceration contributes to higher infant mortality rates, and when children’s fathers go to prison, their mothers are more likely to suffer negative mental health consequences. Overall, the scientific research suggests that the health of Black Americans is hit particularly hard by disproportionate incarceration (Schnittk, Massoglia, and Uggen, 2011).

We are all products of our life experiences – good, bad, and indifferent – and we are less individualistic than we might think (Fischer, 2008). Although we have the right to choose how to believe and act, research tells us our daily choices are influenced by our society, culture, and social institutions in ways we do not even realize. A recent example we can all relate to is the state shutdowns, social distancing, and mandatory masks in public during the COVID-19 pandemic. For most, our decision to wear masks was not one we always made out of free will, but had more to do with societal and institutional influence. Evidence suggests that Black, Latinx, and Asian Americans in the United States were more likely to wear a face mask in response to COVID-19 than white men (Hearne and Niño, 2021). Sociologists explored why people of color were more likely to wear masks and found intersections between race, gender, and men’s conformity to masculine norms helped explain these differences (Mahalik et al., 2021).

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for What You Need to Know Before Reading This Book

Open Content, Original

Figure 1.4. Image by Shanell Sanchez and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, using data from Pew Research Center, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“What You Need to Know Before Reading This Book” is adapted from “1.1 Chapter Introduction” by Jessica René Peterson and Taryn VanderPyl, in Introduction to Criminology: An Equity Lens, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include expanding for clarity and direct application to this book.

Figure 1.2. “Vote Here Vote Aquí” by Jon Scheiber is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 1.3. Screenshot © Donald J. Trump via Twitter is included under fair use.

Figure 1.5, left. “Man in Gray Long Sleeve Shirt Wearing Facemask” by Adrian Agpasa is licensed under the Pexels License.

Figure 1.5, right. “bIMG_1235” by Becker1999 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

a cumulation of cultural values and norms from a period

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and ethnicities

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups