1.4 The History and Meaning of Race

Race is a concept most of us are familiar with, but often unsure how to define. People often struggle to identify their race, much less the race of others. To further complicate our understanding of race, fallacies or mistaken beliefs about race and racial differences are perpetuated in society. These fallacies are often rooted in bad science, racism, and prejudice. The concept of race is a social and political construct and is constantly changing. Race refers to a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature. However, race is much more complex. Ever since white Europeans began colonizing populations of color, over 300 years or so, race has served as the “premier source of human identity” (Smedley, 1998:690). The “one-drop rule” began in the 1600s, and it said a person was to identify as Black if they had at least one drop of “Black blood.” It was developed to keep the slave population as large as possible while the South relied on farming for its economy on agriculture (Wright, 1993). But as you’ll see, the biological concept of race is illogical or unreasonable.

Most people think of race in biological terms. Although people differ in the many physical features that led to the development of such racial categories, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists question the value of these categories and the value of the biological concept of race (Smedley, 2007). Many scientists doubt that racial differences exist in the world. In today’s world, these differences have become increasingly blurred. Allowing ourselves to see race through a sociological lens reinforces how seeing race through a biological lens poses threats to people based on culture and identity. In this book, we will focus on moving from race as a concept rooted in biological terms to a more sociological understanding of race. Please watch the following video to learn more about the myth of race.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnfKgffCZ7U&t=1s

Alan Goodman (2003) interviewed with PBS and explained the illusion of race as biology, like this:

“But what is important is that race is a very salient social and historical concept, a social and historical idea. It’s shaped institutions, it’s shaped our legal system, it shapes interactions in law offices and housing offices and in medical schools, in dentists’ offices. It shapes that. And I think by stripping the biology from it, by stripping the idea that race is somehow based in biology, we show the emperor to have no clothes, we show race for what it is: it’s an idea that’s constantly being reinvented, and it’s up to us about how we want to invent it and go ahead and reinvent it. But it’s up to us to do it. Racism rests in part on the idea that race is biological; it is based on biology. So, biology becomes an excuse for social differences. The social differences become naturalized in biology. It’s not that our institutions cause differences in mortality; it’s that there are biological differences between the races.”

Because people thought Black people were biologically inferior (Reinhardt, 1927), they suffered violence and discrimination. During slavery and following Emancipation, Black women faced dangers because of their race and sex. Black women were killed in lynchings and massacres that also took the lives of Black men. However, Black women also suffered from the trauma of sexual violence, including rape by mobs of white men (Equal Justice Initiative, 2023). Even before the Civil War’s end, Southern state legislatures implemented laws providing different sexual protections to white women and Black women. For example, the Georgia Code of 1861 specified a mandatory sentencing range for raping a white woman but let courts decide whether and how to punish Black women who were raped. This shielded white men from shame and consequence when they employed sexual assault as yet another means of terrorizing Black communities during Reconstruction (EJI, 2023). Because Black people were viewed as biologically inferior, they were vulnerable to violence and murder that was justified by those who hurt others.

Individuals or groups are placed into racial categories based on arbitrary factors. For example, a century ago, Irish, Italian, and Eastern European Jewish people were not regarded as white upon arrival in the United States, but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they experienced in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European. In this context, consider someone in the United States with white and Black parents. Today in the United States, people would say this person is Black, even though this person’s ancestry is biracial or mixed; they are likely to be considered Black, and that would be their primary racial identity. In many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white. In Brazil, people are identified as Black if they have no European (white) ancestry. If we followed this practice in the United States, about 80 percent of the people we call “Black” would now be called “white.”

A third reason to question the biological concept of race stems from the field of biology itself, specifically from studies in genetics and human evolution. People from different races are more than 99.9 percent the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1 percent of all the DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people we associate with race. People with different racial backgrounds are much more similar than dissimilar. Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, the human species began hundreds of thousands of years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world, people naturally adapted and changed over time through a process known as natural selection. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator) because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. Natural selection favored light skin in people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skin there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone and Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in superficial ways associated with their appearances: we are one human species composed of people who look different.

Activity: Changing Demographics and White Nationalism

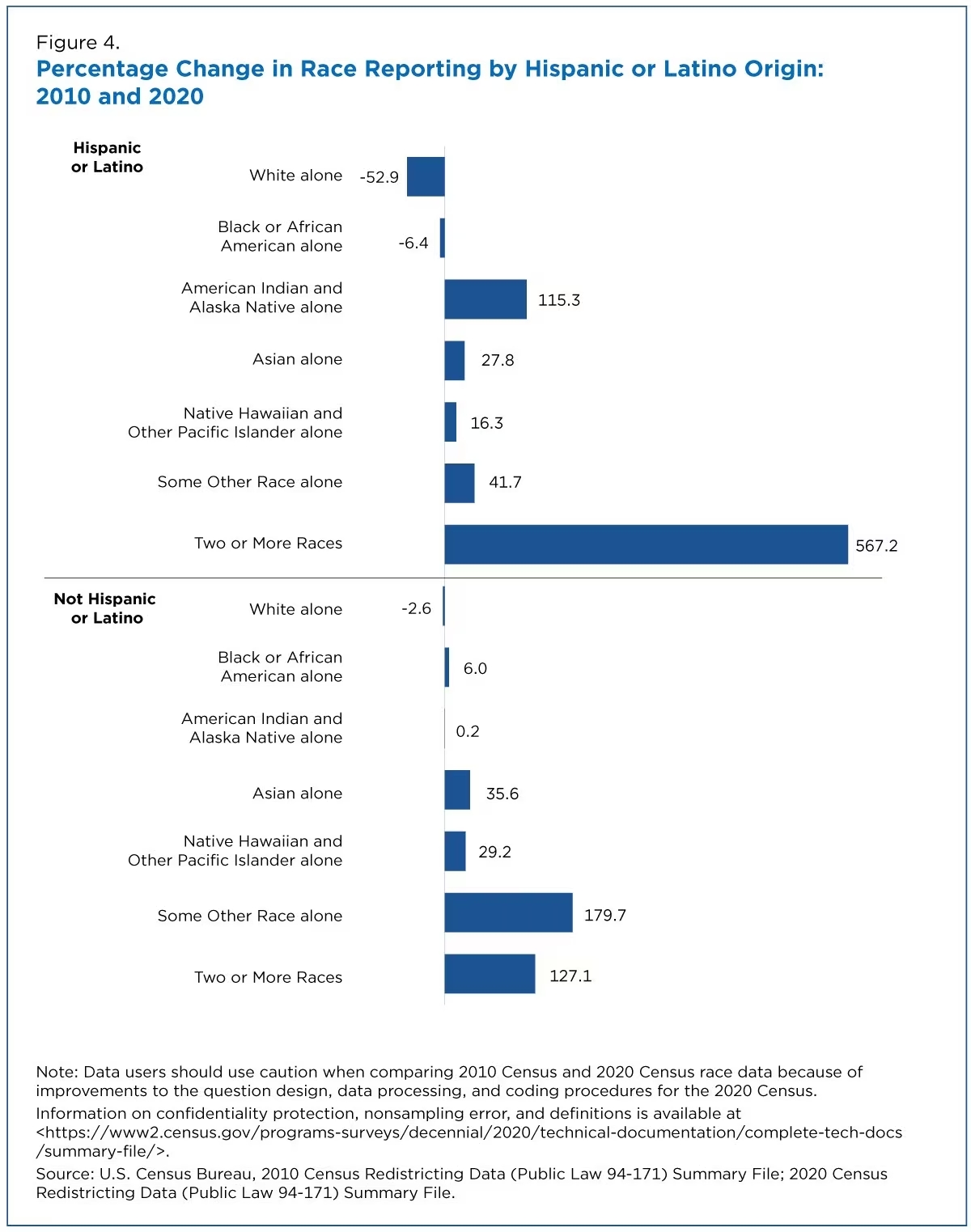

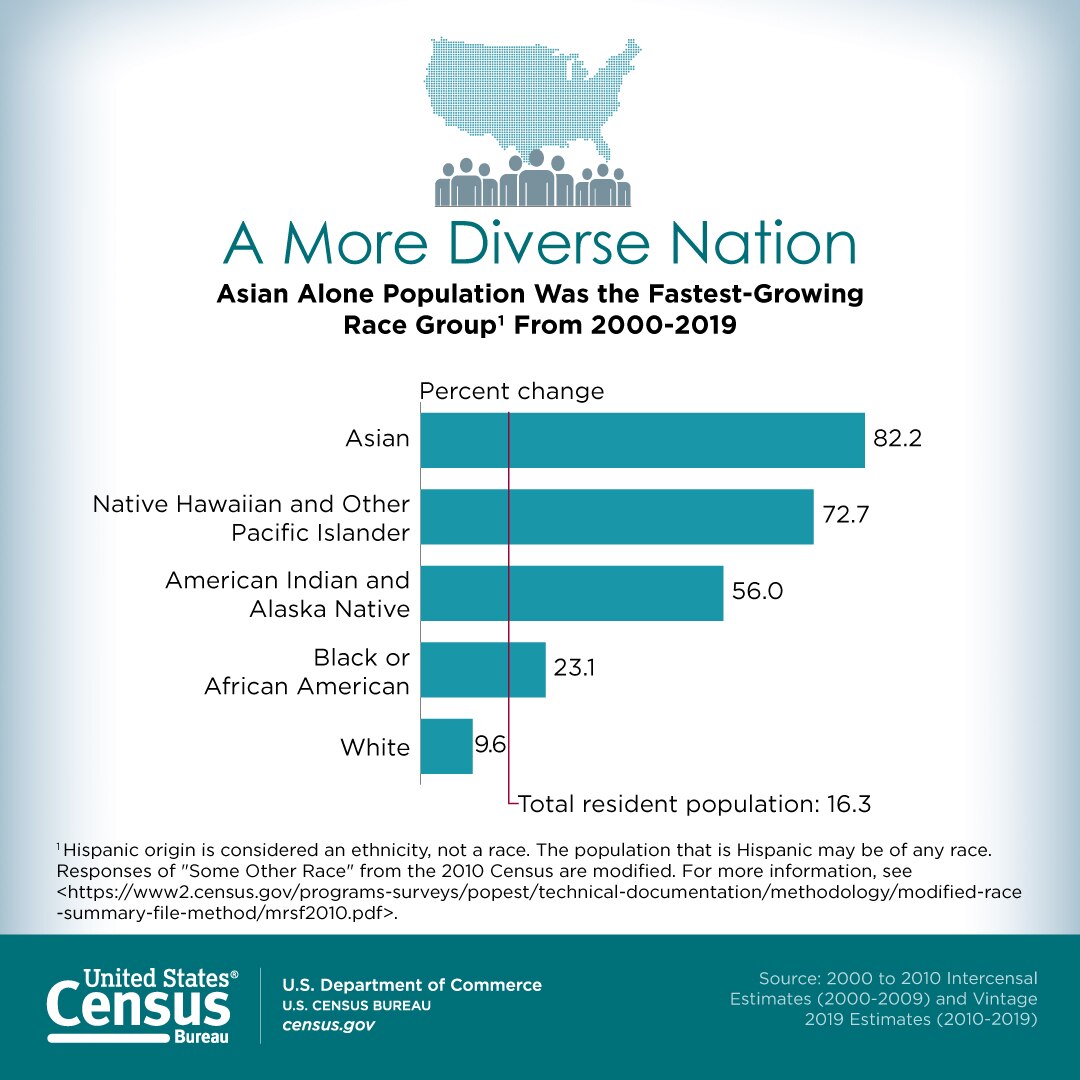

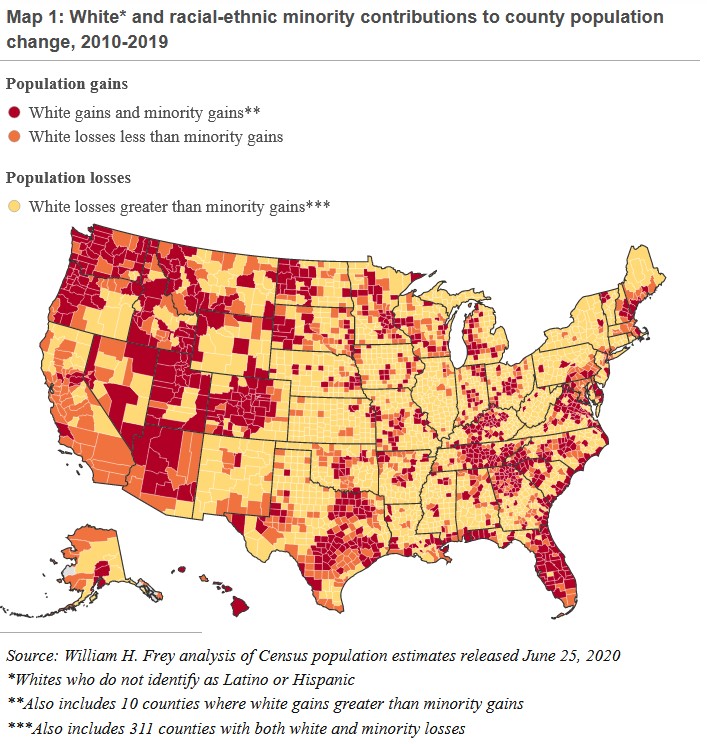

The United States has been diversifying faster than expected, while the white population is declining. According to the 2020 Census, 27 states and 47 of the 100 largest metropolitan areas showed white population losses since 2010. We are seeing increased diversity in the younger population. For example, more than half of the people under 16 in the United States identify as a racial or ethnic minority. Research shows mixed-race individuals have grown within the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). The fastest-growing racial group in the United States is people identifying with two or more racial groups. By 2045, racial and ethnic groups now considered to be minorities will become nearly half the U.S. population. Immigration is said to be the key driver in this rapidly diversifying United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020; Pew Research Center). Estimates are that by 2045, white people will represent the minority of the population.

Changing demographics have had far-reaching impacts on society. Extremism is on the rise across the United States and globally. One form of extremism is white nationalism, which is the idea that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups, and they want to preserve their way of life through a white ethnostate Some of these groups could include the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Confederate, neo-Nazi, racist skinhead, and Christian Identity, and could also be fairly described as white nationalist (SPLC, 2022). White nationalists want a segregated geographical area, preferential treatment, and legal protections for white people (SPLC, 2022). Research attributes this increase in white nationalism to changing demographics that reflect a decline in the white majority, economic instability in the job market of white people, the increased presence of racial and ethnic people in spaces predominantly dominated by white people,e as politics, and cultural changes and shifts. The changing racial demographics of America contribute to our previous conversation about Trump’s success as a presidential candidate among white Americans whose race/ethnicity is central to their identity. When white Americans are told that non-white racial groups will outnumber their group, research has found this causes them to become concerned about their status and influence on society as a group (Major, Blodorn, and Major Blascovich, 2016).

As the United States continues to diversify, the call for attention to the needs and experiences of people of color will become increasingly important. Research has shown that the dominant white culture continues to suppress people of color through policy changes. Advocates for criminal justice reform argue the system’s racist underpinnings are critical to understanding meaningful change.

Considering the above and your research, discuss these prompts with a group or your class:

- How can we create a safe and open environment to discuss sensitive topics like changing racial and ethnic demographics or white nationalism without reinforcing stereotypes or creating divisions in our community?

- Do a little research – how do demographic changes and the rise of white nationalism in the United States compare to similar trends in other countries? What lessons can be learned from looking at efforts across the globe to address ethnic and racial tensions?

- What strategies can community leaders and policymakers adopt to foster inclusion, equity, and mutual understanding as the United States continues to diversify?

Race as Social Construction

Although race is a social construction, it has real consequences. Even though so little DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with race, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but to treat them differently – and, more to the point, unequally – based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows little scientific basis for the current racial classification system that is the source of so much inequality. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction, a concept with no objective reality, but is what people decide it is (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). Let’s talk about golfer Tiger Woods, who was typically called Black by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, even though his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth Black (Leland and Beals, 1997). Despite being multiracial, most people refer to Woods as a Black man.

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race and the racist policies/systems that support it. During slavery in the South, women and girls were raped by plantation owners and other white people. As it became difficult to tell who was “Black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People accused of having Black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998). Often, unjust outcomes occurred for the victims of rape, and the system worked to reinforce racism. We would consider this an example in history where the criminal justice system supported a racist system and racism.

Sociologist Howard Winant says world history has always been racialized (2000). Race remains incredibly important and needs more attention to understand its far-reaching impacts. Post-Civil Rights movement, some people argued that we are in a post-racial society, which will be further discussed in later chapters. But this is proven to be untrue. However, we will learn that proper policy implementation will determine their level of effectiveness. One benefit of taking a sociological perspective is recognizing that our social identity, such as race, is integral to understanding our life experiences. People of color encounter numerous social, economic, and political barriers. W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) wrote in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903 that the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line. He defined the color line as the social separation between races and how this differentiation contributes to lost opportunities and privileges for darker-skinned individuals (BlackPast, 2007). Du Bois was one of the first sociologists to conceptualize race and recognize the importance of race in society. You will read more about racialized socialization and DuBois in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.

Learn More: Susie Guillory Phipps and Racial Labels

In New Orleans in 1982, Susie Guillory Phipps went to court to have herself and her parents and blond, blue-eyed siblings declared “white.” At 48, pale, raven-haired Phipps, who had married a white man and had always been known as white, had obtained her birth certificate to get a passport and discovered she was designated as “colored” (the term used at that time for people of color) in the 1930s. She was a great-great-great-great-granddaughter of a slave, Margarita, who had had a child in 1770 by a white French planter. The state’s lawyers challenged her claim to be white because she was three-thirty-seconds Black, and they won. As mentioned above, Phipps’ classification fell under the “one-drop rule” that designated people as Black if their ancestry was at least one-thirty-second Black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was Black) (Jaynes, 1982). Phipps spent over $20,000 on legal fees to change the law that declared her “colored.” Her lawyer argued that anyone who saw her would identify her as a white person, not Black or mixed. The Orleans Parish Civil District Court heard the case in Louisiana. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi and Winant, 1994). Why would Phipps spend so much money to fight an arbitrary label? Sociologists would say it is because race is real in its consequences, even if it is not real in its meaning.

Ethnicity

Many social scientists prefer the term ethnicity in speaking of people of color and others with distinctive cultural heritages. In this context, ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different. Ethnicity and ethnic groups avoid the biological connotations of race and racial groups. People gain a sense of identity from belonging to an ethnic group. Ethnic identities can give individuals a sense of belonging. National surveys found that more than three-fourths of people say they feel close or very close to their ethnic heritage. The term ethnic pride captures the sense of self-worth that many people derive from their ethnic backgrounds. More generally, group membership is a part of socialization, and ethnicity certainly plays a role in the socialization of millions of people. Ethnic groups have rituals, customs, ceremonies, and other traditions to help preserve a shared heritage (Kottak and Kozaitis, 2012). Lifestyle requirements and other identity characteristics, such as where we grew up, the food we prefer, and the traditions we participate in, come from our ethnic group (Kottak and Kozaitis, 2012).

Ethnicity is not immune to strife. Around the world today, ethnic conflict occurs. One form of ethnic conflict is ethnic cleansing. The term ethnic cleansing surfaced in the context of the 1990s conflict in the former Yugoslavia and is considered to come from a literal translation of the Serbo-Croatian expression “etničko čišćenje.” Targeted ethnic groups were Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbs in the Krajina region of Croatia, and ethnic Albanians and later Serbs in the Serbian province of Kosovo. The term also has been attached to the treatment by Indonesian militants of the people of East Timor, many of whom were killed or forced to abandon their homes after citizens there voted in favor of independence in 1999, and to the plight of Chechens who fled Grozny and other areas of Chechnya following Russian military operations against Chechen separatists during the 1990s (Andreopoulos, 2024). The concept of ethnic cleansing has become firmly anchored within international law. However, it remains to be seen how mechanisms to prevent and deal with ethnic cleansing will develop and be implemented.

The United Nations (2023) states coercive practices used to remove the civilian population can include murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, extrajudicial executions, rape, and sexual assaults, severe physical injury to civilians, confinement of civilian population, forcible removal, displacement and deportation of the civilian population, deliberate military attacks or threats of attacks on civilians and civilian areas, use of civilians as human shields, destruction of property, robbery of personal property, attacks on hospitals, medical personnel, and locations with the Red Cross/Red Crescent emblem, among others. According to a report issued by the United Nations (UN) secretary-general, the frequent occurrence of ethnic cleansing in the 1990s was attributable to the nature of contemporary armed conflicts, in which ethnicity, like race, continues to be an identification method that individuals and institutions use today – whether through a census, affirmative action initiatives, non-discrimination laws, or simply personal day-to-day relations (United Nations, 2023).

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for The History and Meaning of Race

Open Content, Original

“The History and Meaning of Race” by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Ethnicity” is adapted from “4.4 Racism” by Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, and Joy Tsuhako, Race and Ethnic Relations in the U.S.: An Intersectional Approach, Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, and Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI), which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez and Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include remixing, editing for style, and adding U.S. examples.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.11. “The myth of race, debunked in 3 minutes” by Vox is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 1.12. Photo from “Sexual Violence Targeting Black Women” by Unknown via Reconstruction in America © Equal Justice Initiative, University of South Carolina Archives, is included with permission.

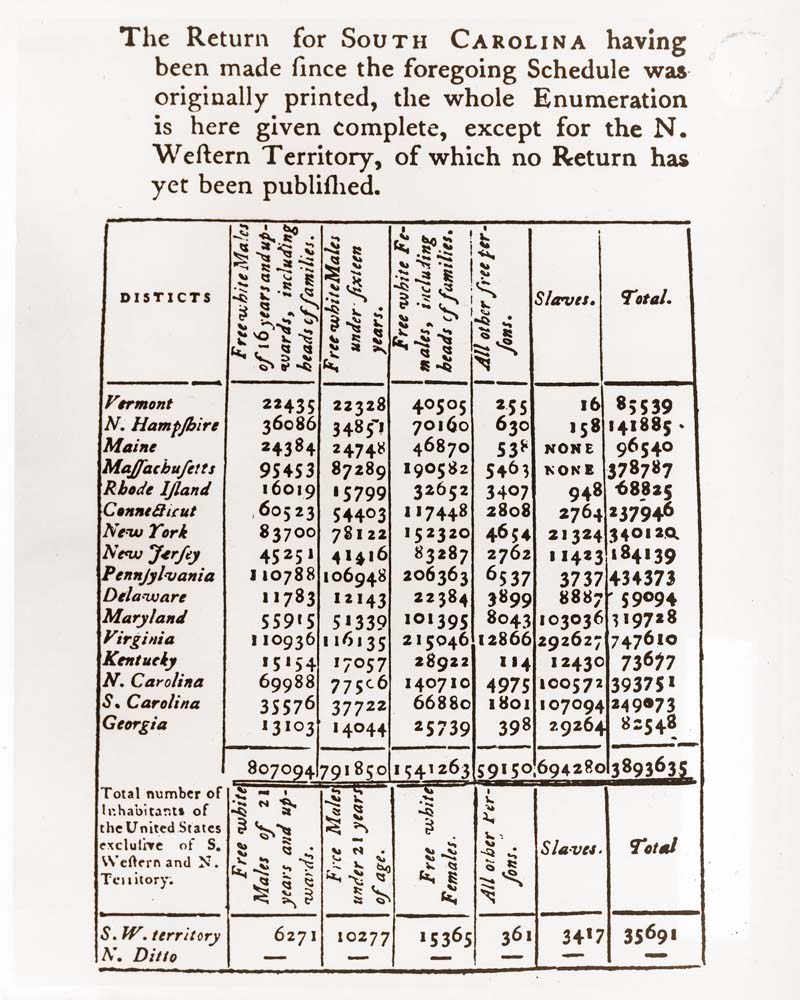

Figure 1.13. 1790 Census Returns by the U.S. Census Bureau are in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.14. “Percent Change in Race Reporting by Hispanic or Latino Origin: 2010 and 2020” from “Improved Race and Ethnicity Measures Reveal U.S. Population Is Much More Multiracial” by the U.S. Census Bureau in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.15. “A More Diverse Nation” by the U.S. Census Bureau is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.16. “White* and racial-ethnic minority contributions to county population change, 2010–2019” from “The Nation is Diversifying Even Faster than Predicted, According to New Census Data” by William H. Frey, The Brookings Institution is included under fair use.

Figure 1.17. Image via the New York Times is included under fair use.

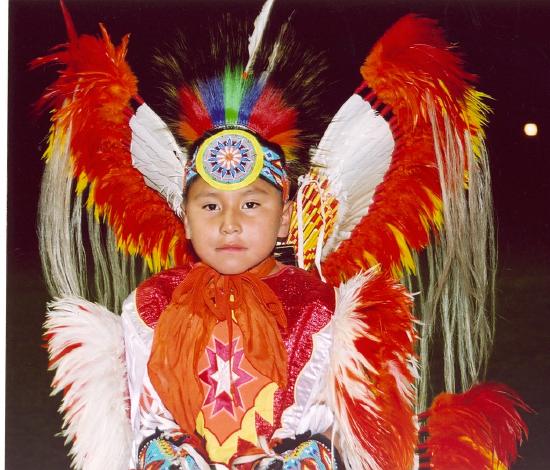

Figure 1.18. “Native American Son” by Bob.Rosenberg via Flickr is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

traits and characteristics people have due to genetics

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

to look something without bias

the process through which people are taught to be proficient members of a society.