3.3 Social Control and Sanctions

When a person violates a social norm, what happens? A driver caught speeding can receive a speeding ticket. A student who texts in class gets a warning from a professor. An adult belching loudly is avoided. All societies practice social control, the regulation and enforcement of norms. Social control can be defined broadly as an organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes, 2003). The underlying goal of social control is to maintain social order, an arrangement of practices and behaviors on which society’s members base their daily lives. Think of social order as your student handbook, and social control as the incentives and disincentives used to encourage or oblige students to follow those rules. When a worker violates a workplace guideline, the manager steps in to enforce the rules. One means of enforcing rules is through sanctions. Sanctions can be positive as well as negative. Positive sanctions are rewards given for conforming to norms. A promotion at work is a positive sanction for working hard. Negative sanctions are punishments for violating norms. Being arrested is a punishment for shoplifting. Both types of sanctions play a role in social control.

Sociologists identify two basic forms of social control as a means to enforce social order (Poore, 2007). The informal means of control are the internalization of norms and values through socialization. The formal means of social control are external sanctions enforced by the government to prevent the establishment of chaos or anomie in society. Someone who commits a crime may be arrested or imprisoned. Some theorists, such as Émile Durkheim, refer to this form of control as regulation. Sociologist Ross argues that belief systems control our behavior through laws that are imposed by the government (Ross, 2009). This could be the use of police to arrest people, incarceration for individuals who are found guilty, or community service as a punishment.

Social control is considered to be one of the foundations of order within society (Ross, 2009). While the concept of social control has been around since the formation of organized sociology, the meaning has been altered over time. A famous sociologist, Michael Foucault (1979), describes modern forms of government as disciplinary social control because they each rely on the detailed continuous training, control, and observation of individuals to improve their capabilities: to transform criminals into law abiding citizens, children into educated and productive adults, recruits into disciplined soldiers, patients into healthy people, and so on. Foucault argues that the ideal of discipline as a means of social control is to render individuals docile. That does not mean that they become passive or sheep-like, but that disciplinary training simultaneously increases their abilities, skills, and usefulness while making them more compliant and manipulable.

The chief components of disciplinary social control in modern institutions like the prison and the school are surveillance, normalization, and examination (Foucault, 1979). Surveillance refers to the various means used to make the lives and activities of individuals visible to authorities. In 1791, Jeremy Bentham published his book on the ideal prison: the panopticon, or “seeing machine.” Prisoners’ cells would be arranged in a circle around a central observation tower where they could be both separated from each other and continually exposed to the view of prison guards. In this way, Bentham proposed, social control could become automatic because prisoners would be induced to monitor their behavior.

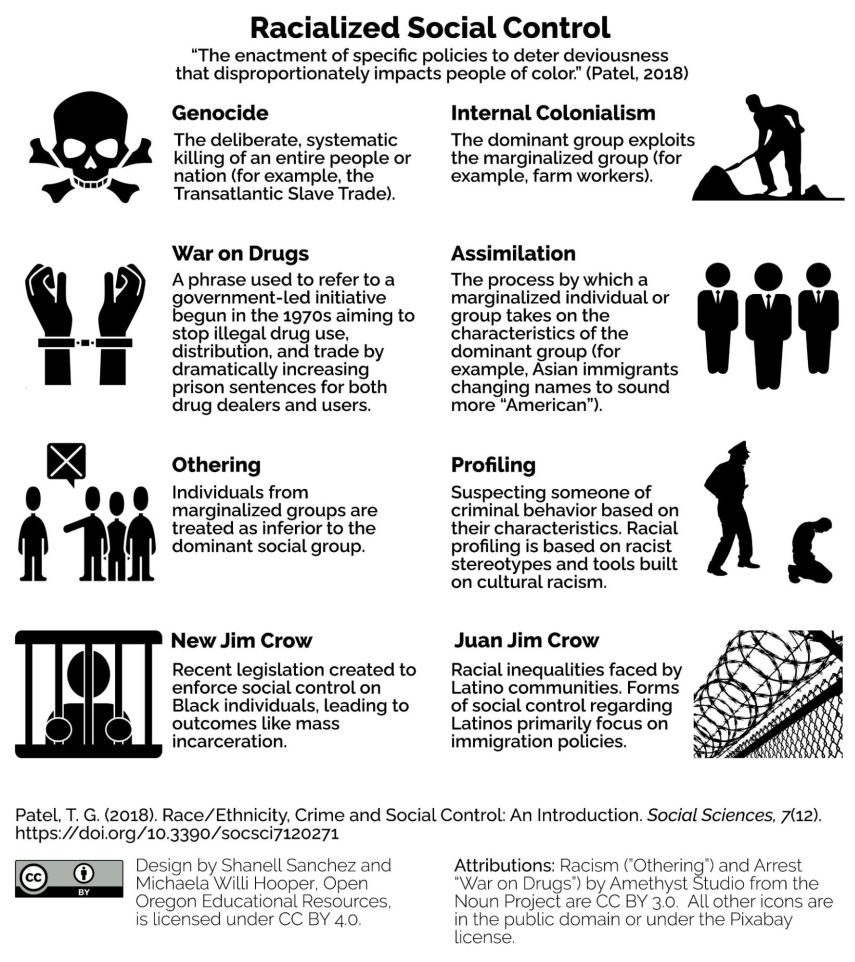

Racialized Social Control

Race and ethnicity are important to consider because they impact people’s outcomes within the criminal justice system, specifically through the creation and enactment of policies aimed at reducing crime. Race, racism, prejudice, and discrimination are deeply entrenched in American society and can begin in the form of policy. A form of crime reduction through what is known as racialized social control. Racialized social control is the enactment of specific policies to deter deviance that disproportionately impacts people of color (Patel, 2018). Sometimes the policies are intentionally designed to have negative impacts on people of color and intentionally control their actions, and other times, it is not, but the negative impacts are still felt.

In the American discussion of crime policy and prevention, crime is often framed as a bad decision made by a bad person. We often fail to discuss systemic issues that led to crime or an individual committing the crime. One such example is the treatment of Black mothers during the War on Drugs. While the effects of crack use during pregnancy are not as severe as alcohol usage, newspapers played on the idea of an upcoming “crack baby” epidemic (Okie, 2009). Headlines during the 1990s painted pregnant Black drug users as irresponsible mothers. Instead of looking at drug addiction as a health issue, the public shunned Black mothers and blamed them for their drug addictions. As a result, many Black mothers were arrested and sent to prison for possessing drugs while they were forced to leave their children behind (ZORA, 2021). When we frame crime as an individual choice, it allows for people to create policies that specifically target individual bad decisions that may result in disparate treatment for people of color.

Some types of criminal behaviors become associated with specific races, which in turn allows for racial minorities to be targeted more. As a result, people of color face more discrimination within the courts, the prison system, and the police. One of the earliest forms of racialized social control began in 1704 in South Carolina. As more white families enslaved people from Africa, they feared that slaves would revolt and gain power. Enslaved people were regarded as inferior, and because of that, many white people believed that they should be treated as such. To combat this fear, a form of policing called Slave Patrols was used, which will be discussed in subsequent chapters. In the 1860s, protections for Black Americans granted them equal rights within the U.S. Constitution (NAACP, n.d.). However, Jim Crow legislation, as discussed in previous chapters, was introduced to keep Black people segregated without outright violating the Constitution. Police departments were used to enforce racialized social control by upholding Jim Crow laws across all states. After the Jim Crow legislation was abolished, legislators began constructing newer and more subtle discrimination tactics.

Learn More: “White Caller Crime”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3662COVmn8

Christian Cooper, a Black man who was simply enjoying bird-watching in Central Park, experienced what law professor Chan Tov McNamarah would call “white caller crime” (McNamarah, 2019) when Amy Cooper decided to call the cops. A confrontation started when Christian asked Amy, a white woman, to put her dog on a leash. The two were in Central Park, located in New York, where it’s required for dogs to be on a leash at all times. Christian explained this to her, but Amy ignored him. Afterwards, Christian started recording. In the video recording, Amy can be seen calling the cops and saying that her life was being threatened by an African man. However, the video shows Christian making no moves toward Amy, and he even asks her to stay away from him. She starts yelling more, saying that her dog and she were being threatened more.

The cell phone recording went viral, and social media quickly identified her. The actions of Amy Cooper brought discussions surrounding the power that white women have when it comes to Black and Brown men. When looking at this case at a basic level, it is undeniable that the hostility Amy Cooper displayed was because of Christian’s race. Intergroup relations theory explains how Amy’s racial prejudice of Christians manifested itself through aggression. Her intolerance of Christians was because he is Black, leading her to discriminate against him and deem his actions devious. In the end, she put Christian’s life in danger because of her racial prejudice. She recognized that if she called the cops, saying that he was threatening her, he would face consequences even if it wasn’t true, and despite knowing that Black Americans face violence by police officers. There were charges against her for false reporting; however, these charges were eventually dropped. This case closely mirrors cases such as Emmett Till, a young Black boy who was lynched after a white woman falsely accused him of sexual harassment. Such cases are examples of people enforcing social control on people of color.

Exclusionary Laws

Chapter 2 discussed discrimination and provided information about some early forms of legal discrimination in the United States, particularly regarding the treatment of Black people, to illustrate the concept from a historical perspective. In this section, we will see a broader focus on different types of exclusionary laws that are part of racialized social control.

In the early history of the United States, governments used vagrancy laws and other forms of banishment to keep “undesirable” people out. For example, in Oregon on June 26, 1844, the legislative committee of the territory then known as “Oregon Country” passed the first of a series of “Black Exclusion” laws. These laws dictated that free African Americans were prohibited from moving into Oregon Country, and those who violated the ban could be whipped “not less than twenty nor more than thirty-nine stripes.” That December, they amended the law to substitute forced labor for whipping. The law stated African Americans who stayed within Oregon would be hired at public auction and that the “hirer” would be responsible for removing the “hiree” from the territory after the prescribed period of forced service was rendered (Equal Justice Initiative, 2023). This law was enforced even though slavery and involuntary servitude were illegal in Oregon Country.

The preamble to a later exclusion law passed in 1849 – in incredibly outdated and racist language – explained legislators’ beliefs that “it would be highly dangerous to allow free Negroes and mulattoes to reside in the Territory, or to intermix with Indians, instilling…feelings of hostility toward the white race.” The Oregon Constitution of 1857 included racial exclusion provisions against African Americans and Asian Americans by stating African Americans outside of Oregon were not permitted to “come, reside, or be within” the state. Further, they were prohibited from owning property or performing contracts, and punishment would be formally given for those who employed, “harbor[ed],” or otherwise helped African Americans (EJI, 2023). It became apparent that laws were being written to intentionally target people of color in Oregon, which starts to give us a glimpse of racialized social control. These laws have had long-lasting effects on Oregon, as the 2020 Census reported that only 3.2 percent of Oregon residents were Black. Portland has the highest share of white residents among the most popular cities in the United States (The Oregonian, 2022). In the 1960s and 1970s, however, these exclusion orders were denounced as unconstitutional in America (Herbert and Beckett, 2009) and consequently were rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court (Beckett and Herbert, 2008).

The introduction of broken windows theory in the 1980s generated a dramatic transformation in the concepts used in forming policies to circumvent the previous issue of unconstitutionality (Harcourt and Ludwig, 2005). According to the theory, the environment of a particular space signals its health to the public, including potential vandals. By maintaining an organized environment, individuals are dissuaded from causing disarray in that particular location. However, environments filled with disorder, such as broken windows or graffiti, indicate an inability for the neighborhood to supervise itself, therefore leading to an increase in criminal activity (Ranasinghe, 2010). Instead of focusing on the built environment, policies substantiated by the broken windows theory overwhelmingly emphasize undesirable human behavior as an environmental disorder prompting further crime (Beckett and Herbert, 2008). The civility laws, originating in the late 1980s and early 1990s, provide an example of the usage of this latter aspect of the broken windows theory as legitimization for discriminating against individuals considered disorderly to increase the sense of security in urban spaces (Herbert and Beckett, 2009). These civility laws effectively criminalize activities considered undesirable, such as sitting or lying on sidewalks, sleeping in parks, urinating or drinking in public, and begging (Beckett and Herbert, 2010) in an attempt to force the individuals doing these and other activities to relocate to the margins of society (Beckett and Herbert, 2009). Not surprisingly, then, these restrictions disproportionally affect the homeless (Beckett and Herbert, 2008).

Individuals are deemed undesirable in urban spaces because they do not fit into social norms, which causes unease for many residents of certain neighborhoods (England, 1997). This fear has been deepened by the broken windows theory and exploited in policies seeking to remove undesirables from visible areas of society (Ranasinghe, 2010). In the post-industrial city, concerned primarily with retail, tourism, and the service sector (Beckett and Herbert, 2008), the increasing pressure to create the image of a livable and orderly city has no doubt aided in the most recent forms of social control (Beckett and Herbert, 2009). These new techniques involve even more intense attempts to spatially expel certain individuals from urban space since the police are entrusted with considerably more power to investigate individuals, based on suspicion rather than on definite evidence of illicit actions (Beckett and Herbert, 2010).

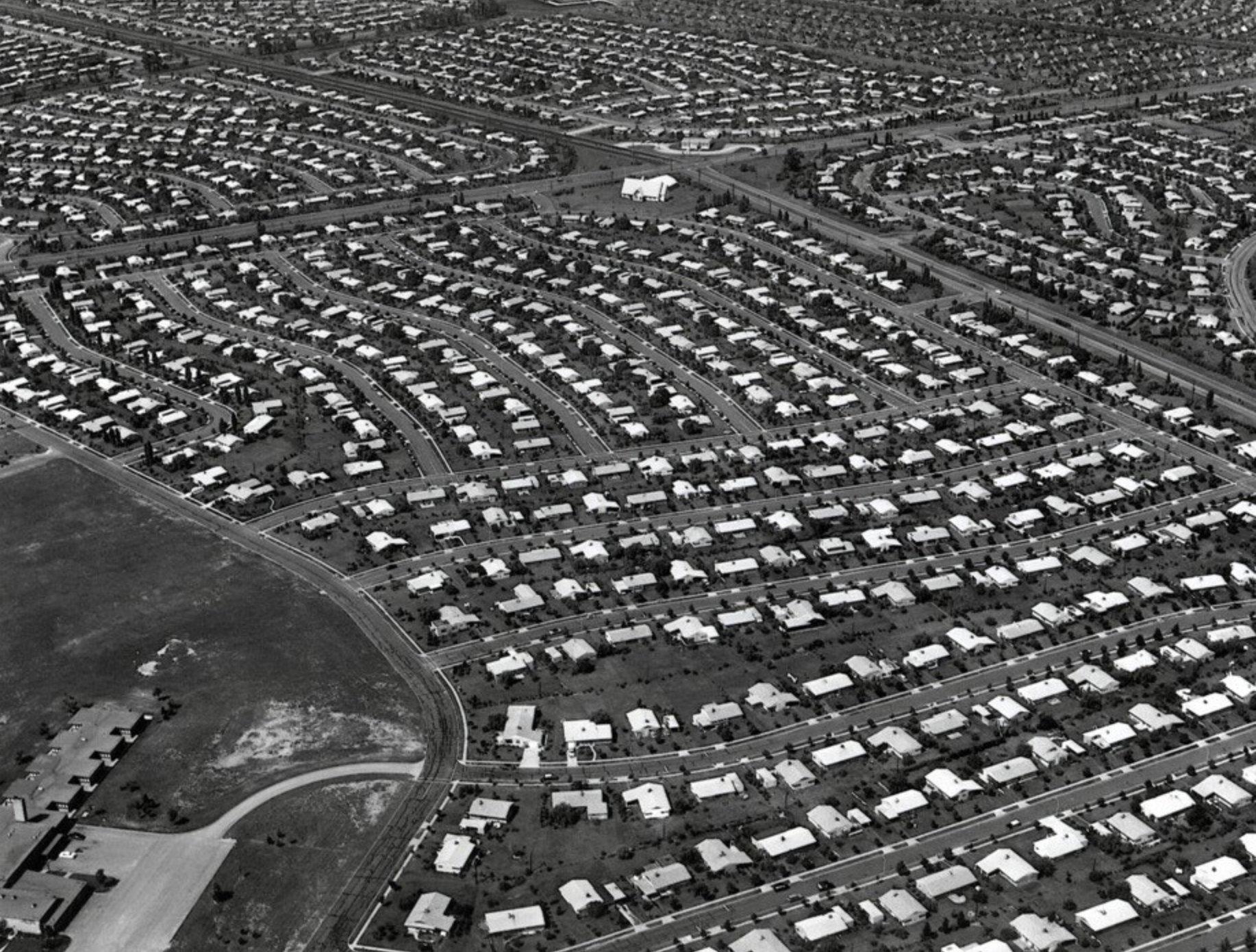

Learn More: Federal Government Builds White Suburbia

Federal housing policies denied opportunities to Black residents, while subsidizing and safeguarding white-only neighborhoods. Federal, state, and local governments consciously segregated our metropolitan areas by race through policy. Black communities continue to be impacted by housing discrimination. Federally funded public housing started with the New Deal. When Harold L. Ickes, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, proposed the “Neighborhood Composition Rule” in 1968, he effectively secured racial segregation in housing. After World War II, the Federal Housing Administration (a precursor to HUD) and the Veterans Administration hired builders to mass-produce American suburbs. Some commonly referenced examples were Levittown near New York to Daly City in the Bay Area, to ease the post-war housing shortage (Capps, 2015). Hired by both the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration, these property builders were given federal loans on the condition that they refuse Black families from residing in newly constructed suburbs. These neighborhoods were created to be exclusively white, and Black families were refused the chance to live in these houses to maintain segregation. This rule enforced the separation of Black people and white people within public housing. After the U.S. Supreme Court attempted to reduce segregation, the city of Baltimore looked for a way around these laws. An official Committee on Segregation was created to build neighborhood associations, which restricted white real estate agents and property owners from selling and renting to potential Black homebuyers. Even now, we can see the effects of housing segregation still in effect. Projects such as the Levittown suburb, constructed in Long Island, show major differences in racial demographics. The racial covenants built in 1947 made it so that only white homebuyers could own property there. It is now reflected in Levittown, with less than 1 percent of people residing in Levittown identifying as Black and 89 percent of residents identifying as white. Meanwhile, New York witnesses a population of 26 percent Black residents and around 44 percent white residents, indicating that Levittown’s segregation has effectively kept Black people out. Unfortunately, the federal government still identifies racial segregation in housing as an individualistic choice, not an issue built around racist laws (Capps, 2015). Relatedly, you will learn more about the practice of redlining in Chapter 4.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Social Control and Sanctions

Open Content, Original

“Learn More: Federal Governments Build White Suburbia” by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.4. “Racialized social control” by Shanell Sanchez and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Icons: “Racism” (”Othering”) and “Arrest” (“War on Drugs”) by Amethyst Studio are licensed under CC BY 3.0. All other icons are in the Public Domain or under the Pixabay license.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Control and Sanctions” is adapted from “Socialization” by William Little and Ron McGivern, Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition, BCcampus, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez and Catherine Venegas-Garcia, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, include rewording and elaborating points related to criminal justice.

“Racialized Social Control” and “Exclusionary Laws” are adapted from “Social Control” by Lumen Learning, Cultural Anthropology (Evans), which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications by Shanell Sanchez, revised by Jessica René Peterson, licensed CC BY-SA 4.0, include rewording and elaborating points related to criminal justice.

Figure 3.3. “Signs warning of prohibited activities; an example of social control” by Svenska84 is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.6. “Levittown” is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.5. “Amy Cooper Made 2nd Call To 911 About Black Birdwatcher, Prosecutors Say” by TODAY is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes 2003).

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

the process through which people are taught to be proficient members of a society.

the scientific and systematic study of human relationships, institutions, groups and group interactions, societies, and social interactions, from small and personal groups to large groups

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

the enactment of specific policies to deter deviousness that disproportionately impacts people of color (Patel, 2018).

an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica 2023).

groups of predominantly white men who would hunt down, punish, and return runaway Black people to their legal enslavers. Developed in 1704 in South Carolina, these patrols became the first publicly funded police agencies in the Southern region of the United States

the way people who belong to social groups or categories perceive, think about, feel about, and act towards and interact with people in other groups.

theory introduced in the 1980s suggesting the environment of a particular space signals its health to the public, including potential vandals, and that by maintaining an organized environment, individuals are dissuaded from causing disarray in that particular location; this theory dramatically transformed policing policies and practices that had a major impact on people of color