5.2 The History and Evolution of American Policing

Imagine that you woke up tomorrow morning and there were NO laws or criminal justice system. What do you think the modern world would look like? What would your day look like as you travel to and from work or school? When I ask this question, the most common immediate responses are: “Chaos! Anarchy! The Purge!” Laws may certainly help regulate our interactions with each other, maintain order, or mandate punishments, but how do they do those things?

We cannot talk about the police without also discussing the laws they enforce. Police officers are the law enforcement branch of the criminal justice system, the first of the “3 Cs,” consisting of cops, courts, and corrections. Their role is robust, but the primary function of American police is to enforce federal and state laws.

For this discussion, we are going to focus on some of the ways that law and enforcement go together. To better understand the evolution and current state of policing in the United States, especially how policing impacts marginalized communities, we have to ask ourselves, who makes the laws, who is the target of those laws, and how are those laws enforced?

Historically, white male Christian landowners held the power in our communities. At best, this still meant that social norms, beliefs and values that are generally agreed upon in a society, and laws came from the perspective of a single gender, race, and religion. At worst, norms and laws intentionally disadvantaged other groups and maintained an unequal power structure. However, laws’ power comes through their enforcement.

Early American Police

Police officers were not always part of a formal profession as they are now in the United States. In colonial America, policing was informal and unorganized, locally led, and consisted of officers who were untrained and even sometimes unpaid. Initial patrols were used to protect the interests of the powerful and were involved in apprehending wrongdoers, enforcing colonial control over Indigenous peoples, and maintaining the status quo of power. Indigenous peoples in the United States were regarded as dangerous savages from whom settlers needed protection. In colonial America, evidence suggests that early cities appointed “Indian Constables” specifically to police and protect settlers from the Native American population (Bailey, 1995).

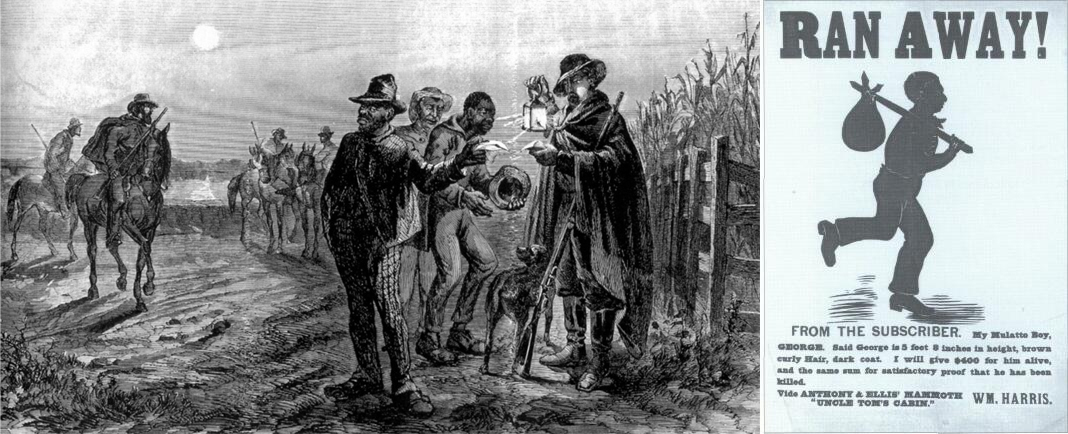

Black people were enslaved in the colonial United States throughout the 17th and 18th centuries to work in construction, on farms, and in homes. In 1704, South Carolina developed slave patrols. These groups of predominantly white men regulated the behavior of enslaved Black people and those who escaped their captors, as shown in Figure 5.3. They would hunt down, punish, and return runaway individuals to their enslavers, sometimes with the use of dogs specifically trained in this task, known as “negro dogs” (Spruill, 2016). These patrols became the first publicly funded police agencies in the Southern region of the United States. To learn more about the relationship between slavery and American policing, you can watch the video “How American Slavery Helped Create Modern-Day Policing” in the Chapter Resources.

As slavery continued in the newly established nation, formal police departments began professionalizing in cities like Boston, New York, and St. Louis to combat increasing crime. Additionally, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, adopting the slave patrol practice that began in South Carolina almost 150 years prior. This federal law required that enslaved people who ran away be returned to their “masters” and allowed police officers to arrest anyone they thought was a runaway slave. The slave patrols were notoriously violent, brutally maiming or murdering while doing their duties. Free Black individuals were often harassed by these patrols as well. To discourage people from helping Black individuals who escaped, the law also allowed anyone who helped runaway slaves with food, water, or shelter to be sentenced to six months in prison or given a $1,000 fine, which would be more than $31,000 in 2023 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023).

Although the unification of police departments from the 1830s to the 1850s is widely accepted as the origin of professional policing in America, the existence of slave patrols that were informally and formally sanctioned by the government since the early 18th century cannot be ignored. The Fugitive Slave Law and this early form of policing in the United States reinforced, sometimes violently, an unequal power structure between free and enslaved people as well as white and Black people. The laws and their enforcement classified the Black population as inferior to the white population. Although slavery legally ended in 1865, the unequal enforcement of the law and culture of oppression against Black people did not.

Policing “Separate but Equal”

Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, slave patrols continued operating with the help of government military groups and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Throughout colonial America, particularly in the South, slavery had become politically and economically significant, and they did not want to give up social control over the Black population. Laws known as the “Black Codes” were quickly enacted in the South that limited Black individuals’ employment, travel, land ownership opportunities, freedom, and voting.

For example, South Carolina required Black people to pay an annual tax of up to $100 unless they worked as a farmer or servant (Onion et al., 2010). This would equal more than $3,000 in 2023 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Black citizens in Texas were prohibited from serving on a jury or using profanity at work (Texas Black Codes, Chapter LXXX, Section 9). Violating these codes was a crime and meant that Black people could now be arrested and punished via enslavement or involuntary servitude, as the Thirteenth Amendment allowed (see Chapter 7 for more). As a result, the Black prison population exploded in the South. Black bodies were again forced into fields through labor systems utilized in prisons.

While prejudice and racism operated at both the federal and local levels throughout the United States, Southern states maintained a firm separation of Black and white citizens through the passage of Jim Crow laws in the late 19th century, as discussed in Chapter 2. Jim Crow laws continued the racist oppression of Black people as they gave police the power to maintain white supremacy in the South. Some locations were completely off-limits to Black people, while many public amenities such as restaurants, bathrooms, water fountains, and phone booths were segregated by race. Put plainly, governments were still allowed to use race or ethnicity as a way to divide access even though the Fourteenth Amendment supposedly provided equal protection to all.

It was not uncommon for police officers to target Black individuals with violence or unjust arrests when enforcing segregation. During this period of time, concerns about both over-policing and under-policing started to come to light (Jett, 2021) and have continued to be issues in modern policing, as we will discuss later.

Policing the Civil Rights Movement

By the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was in full force. Advocates were organizing and fiercely protesting the various civil injustices found in discriminatory laws, policies, and policing practices. Racial and ethnic injustices were particularly rampant in the Southern region of the United States, where Black individuals were denied equal access and protection regarding marriage, voting, education, employment, public services, and more. Police were not only enforcers of the laws that were being challenged, but officers often addressed protests during this time with hostility and violence. Two subcategories within this era are discussed here, including the policing of voting rights and the LGBTQIA+ rights movements.

Voting rights and police violence

Although the Fifteenth Amendment had granted Black men the right to vote in 1870, Southern states enacted laws that made voting incredibly difficult for them. Police enforced poll taxes, literacy exam requirements, and other obstacles to voting, and Black voters faced harassment at the polls. As representation and voting power are hallmarks of a democratic nation, the policing of voting booths became a symbolic stage for the violent oppression of Black citizens.

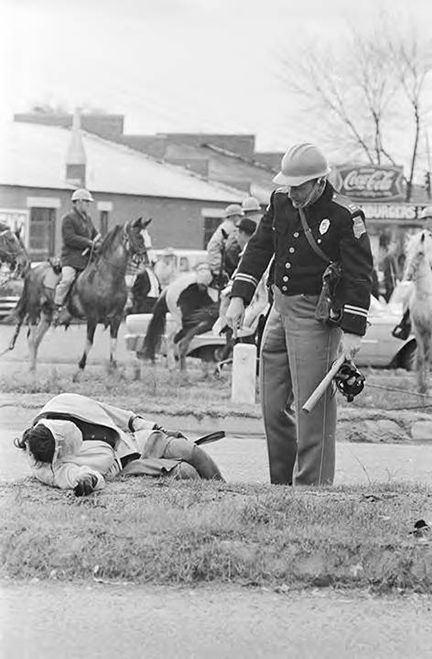

In March of 1965, civil rights activists attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to bring awareness to both the civil and voting rights violations throughout the South, as well as to protest the murder of a Black activist and church deacon by an Alabama state trooper. The first of the three attempts to complete the march became known as Bloody Sunday. When marchers attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they met a blockade of state and local police who ordered them to disperse. When they stood their ground, police advanced on the crowd, attacking them with clubs, sticks, firearms, whips, and tear gas. Officers on horses chased marchers down and beat them. Many protesters were bloodied, knocked unconscious, and suffered bone and skull fractures. Canines were also a major tool used by police during protests and marches such as this one during the Civil Rights Movement.

A second march commenced two days after Bloody Sunday and was again met with violence from police and citizens. The third attempt at the march, led by Lewis Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King Jr., was successful. The violence that met peaceful protesters who were predominantly Black civil rights activists was captured in photos and televised news coverage. The police brutality shocked many viewers and sparked more political and public support for the civil rights and voting movement. If you are interested in hearing a personal account, you can watch “Selma 50 Years Later: Remembering Bloody Sunday” (LA Times, 2015) in the Chapter Resources to hear Amelia Boynton Robinson speak about her memories of the march.

LGBTQIA+ rights and police violence

The gay liberation movement, encompassing the LGBTQIA+ community, was another component of the Civil Rights Movement that hit a peak in the late 1960s. Gender, gender roles, and sexuality were highly regulated by the legal system, and the police harassed community members who did not conform to these social norms. However, the definition of “non-conformity” was subject to police discretion. It was not uncommon for police to raid known gay bars and hangout spots to arrest those who were engaged in “gay behavior,” “soliciting homosexual sex,” or “cross-dressing” in public. One common such location was the Stonewall Inn in New York City.

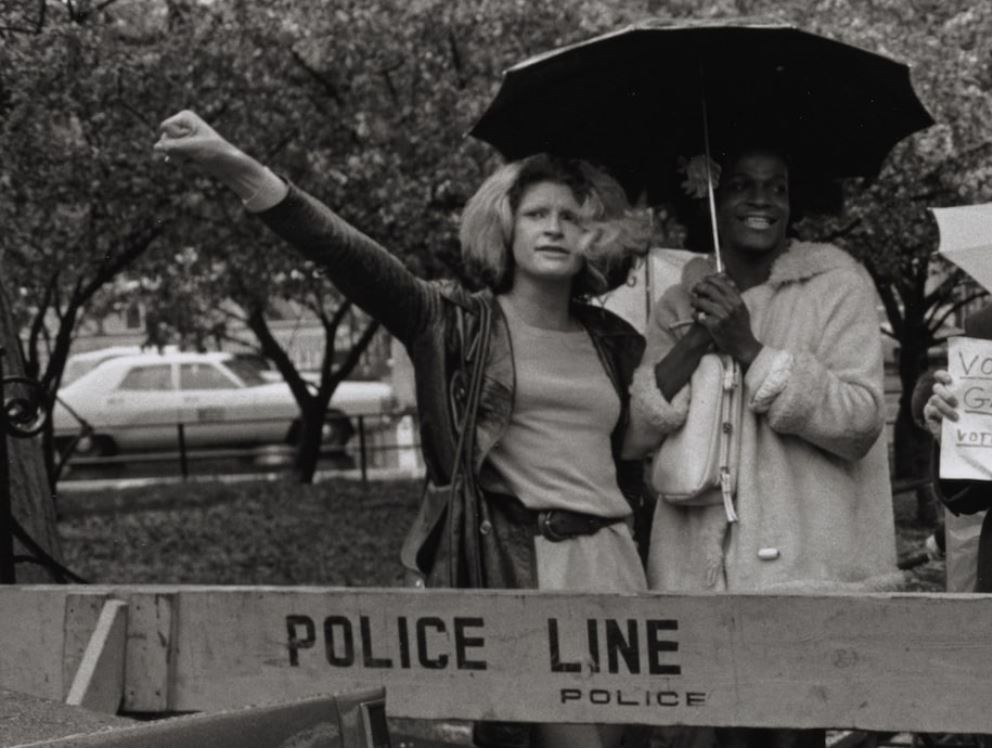

The Stonewall riot was not the only uprising in the gay liberation movement during this time, but it has become the most well-known. Now a national monument, as seen in figure 5.5, the Stonewall Inn was the site of extreme oppression and revolution in 1969. In the early morning of June 28, police raided the bar, but patrons fought back. The ensuing riot lasted six days, and many people of color – facing compounding marginalization as non-white, non-cisgender, and non-heterosexuals – were arrested by police during the raids. One year after the incident, the first Pride event was held to honor the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights.

Although the LGBTQIA+ civil rights movement was not reserved for any particular race or ethnicity, the contributions and leadership of queer Black and Brown people are undeniable. The Stonewall riots and legacy were largely led by LGBTQIA+ women of color, including Stormé DeLarverie, Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy (see figure 5.6). Many queer people of all races and ethnicities protest the presence of police at modern Pride events due to this history of violent oppression at the hands of the police.

Police as Soldiers in the War on Drugs

While Chapter 9 discusses the War on Drugs in detail, this section will focus on the role of the police in it. The police were the primary soldiers fighting the War on Drugs throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and they fought aggressively. Funding for law enforcement increased, and special drug task forces were created at the federal, state, and local levels. As discussed in Chapter 3, Broken Windows Theory – the idea that visible disorder, such as graffiti, dilapidated buildings, or people loitering in the street, led to crime – was one idea that heavily influenced policing strategies during this time (Wilson and Kelling, 1982). Broken Windows policing requires police to focus on petty crimes that indicate disorder, with the assumption that this would reduce more violent crime. This form of policing led to negative impacts on people living in diverse and impoverished communities. Aggressive enforcement through writing citations or making arrests for low-level crimes strained residents’ already thin finances and reduced their trust in the police (Childress, 2016).

Relatedly, zero-tolerance policies and raids became the norm during the “crack epidemic” as police stormed minority communities and arrested all involved, from the users and low-level sellers to the kingpins. Drug-related arrests skyrocketed with police agencies’ targeted, reactive, and proactive enforcement of drug laws (see figure 5.7, for example). Raids on “crack houses” were some of the most visible tactics witnessed by community members and the public at large (Sherman et al., 1995).

Police and public officials also found opportunities to profit from the emerging drug market at the expense of marginalized communities (Flamini et al., 2021). In the early 1990s, a Commission that was established to monitor anti-corruption practices and policies in the New York Police Department (NYPD) reported that, “the explosion of the cocaine and crack trade in the mid-1980s fueled the opportunities for corruption by flooding certain neighborhoods with drugs and cash, and created opportunities for cops and criminals to profit from each other” (Mollen, 1994:27). This flooding of drugs and cash provided officers with many opportunities to steal from those selling drugs “who are unlikely to complain, and to associate with [other] drug dealers who will pay handsomely for police protection” (Mollen, 1994:220). Large groups of police officers were arrested doing just that in cities across the United States, including New York, Washington, D.C., and Miami.

Although we tend to associate the drug war with the last few decades of the 20th century, it is not over. While the laws and policies have changed, including the reduction in the sentencing disparity for crack and powder cocaine in 2010, legislatures and police agencies continue to prioritize criminal justice responses over healthcare approaches to illicit substances. Additionally, drug laws and enforcement practices have and continue to disproportionately apply to and criminalize Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Police still make around 1 million arrests for drug possession each year, and – in 2016 – Black people were being arrested at least three times as often for narcotics and cocaine offenses compared to white people (Equal Justice Initiative, 2019; Sawyer and Wagner, 2023). If you are interested in media that explores the crack epidemic and policing during that time, you can listen to Toddy Tee’s lyrics for the rap song “Batterram” found in the Chapter Resources.

Policing the Southern Border

Immigration has been a topic of interest among politicians and the public throughout American history. During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump reignited fears over border security, particularly along the southern border of the United States. Although it would not be the first physical barrier placed along an international border, Trump’s promise to build a solid wall between the United States and Mexico became a focal point of his platform and supporters.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), consisting of three operational offices, is the largest federal law enforcement agency in the nation that focuses on border security, travel, and trade. Border patrol agents engage in covert surveillance and use technology, horses and dogs, and a variety of land and water vehicles to detect and apprehend undocumented noncitizens (cbp.gov, 2023). The number of border patrol agents has increased dramatically since the 1990s, but they are not equally dispersed. As of 2019, there were over 16,000 agents stationed at the southwestern border sectors compared to approximately 2,000 agents along the northern border sectors (cbp.gov, 2019). In that same year, there were almost 11,000 drug seizure events along the southwestern border compared to nearly 5,000 along the northern border (cbp.gov, 2023).

Along the southern border, primary concerns include the trafficking of humans, drugs, and weapons from Central and South America. Former President Trump infamously claimed throughout his 2016 campaign that the Mexican government was sending criminals, drug dealers, and rapists to the United States (Hee Lee, 2015). The danger of false and unsubstantiated claims like this can be seen in the lynchings of Mexican people that were carried out by the Texas Rangers in the early 1900s (Villanueva, 2017). Not only did Trump largely ignore the topic of crime and security along the northern border, but research on rates of criminal violations does not support the idea that non-natives or undocumented immigrants commit more violent crime than natives (Light et al., 2020; Rosenblum and Kandel, 2012). Nonetheless, barriers and fencing along the border with Canada are limited or non-existent, while the border with Mexico has been flooded with physical barriers (see figures 5.9, 5.10, and 5.11).

Physical obstacles and the related policing tactics at the southern border have raised ethical questions for many and even resulted in lawsuits. The United Nations Refugee Agency expressed particular concern about how border security efforts along the southern border in the United States are impacting the human rights of refugees and asylum seekers (UN.org, 2023). As citizens, we are left with questions such as 1) “Are these measures, number of agents, and the related policing initiatives necessary for border security?”; and 2) “Is the unequal application of these practices at the two major national land borders driven by evidence or racial/ethnic bias?”

If you are interested in watching a documentary that summarizes some of the racial justice issues in the history and evolution of American policing, watch the new documentary Sound of the Police (found in the Chapter Resources).

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for The History and Evolution of American Policing

Open Content, Original

“The History and Evolution of American Policing” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.3, left. “Slave Patrol” by Frederic B. Schell is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.3, right. “Broadside about a Fugitive Slave” is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the Northern Illinois University Libraries.

Figure 5.5. “Stonewall Inn” by Rhododendrites is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.8. “The Mother Of All Rallies Was Not 26” by Stephen Melkisethian is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 5.9. “US-Canada Border Marker” by Jimmy Emerson, DVM is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 5.10. “Recently constructed panels at the new border wall system project east of Douglas, Arizona, on December 14, 2020” is licensed under CC0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.2. Image from the Purge © Universal Pictures is included under fair use.

Figure 5.4. “Alabama state trooper standing over Amelia Boynton after she was knocked down during the attack on civil rights marchers on Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama” © Alabama Department of Archives and History is all rights reserved and included with permission. Courtesy of Alabama Media Group, photo by Tom Lankford, Birmingham News.

Figure 5.6. “Gay rights activists at City Hall rally for gay rights: Sylvia Ray Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, Barbara Deming, and Kady Vandeurs” © Diana Jo Davies, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 5.7. Photo © Douglas C. Pizac/AP is included under fair use.

Figure 5.11. Photo by Eric Gay in “USA TODAY” © Associated Press is included under fair use.

branch of the criminal legal system that controls the behavior of convicted persons including probation, parole, and incarceration

a group of people living in a defined geographic area that has a common culture

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

groups of predominantly white men who would hunt down, punish, and return runaway Black people to their legal enslavers. Developed in 1704 in South Carolina, these patrols became the first publicly funded police agencies in the Southern region of the United States

a group’s shared practices, values, and beliefs.

organized action intended to change people’s behavior (Innes 2003).

an individual attitude based on inflexible and irrational generalizations about a group of people and literally means “judging before.”

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.

the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races and ethnicities

shared social, cultural, and historical experiences of people from common national or regional backgrounds that make subgroups of a population different

Name for March 7, 1965, when police and a citizen posse violently attacked civil rights protestors marching from Selma to Montgomery

decision-making power that law enforcement officers possess for when and how to enforce the law

uprising in the gay liberation movement on June 28, 1969, when police in New York City raided the Stonewall Inn and patrons fought back, leading to a 6-day riot

an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica 2023).

the police practice - based on broken windows theory - of focusing enforcement efforts on petty crimes that indicate disorder, with the assumption that this would reduce more violent crime