7.5 Paths Through the Justice System: The Court System

As described in the previous sections, the experience with the criminal legal system is quite different depending on whether someone is white or a person of color. Since the country’s founding, in which white was identified as the race of power, any person of color faces consistently worse treatment at every single step of the criminal legal process based on centuries of injustice and discrimination. No matter the civil rights progress that has been made in this country since its inception, the criminal legal system remains a method of racialized control and oppression. As a result, there is one path through the system for white people following an arrest (especially those with money) and a rockier path for everyone else. Although these differences are now subtle enough to allow plausible deniability for those in positions of power, the outcomes are undeniable.

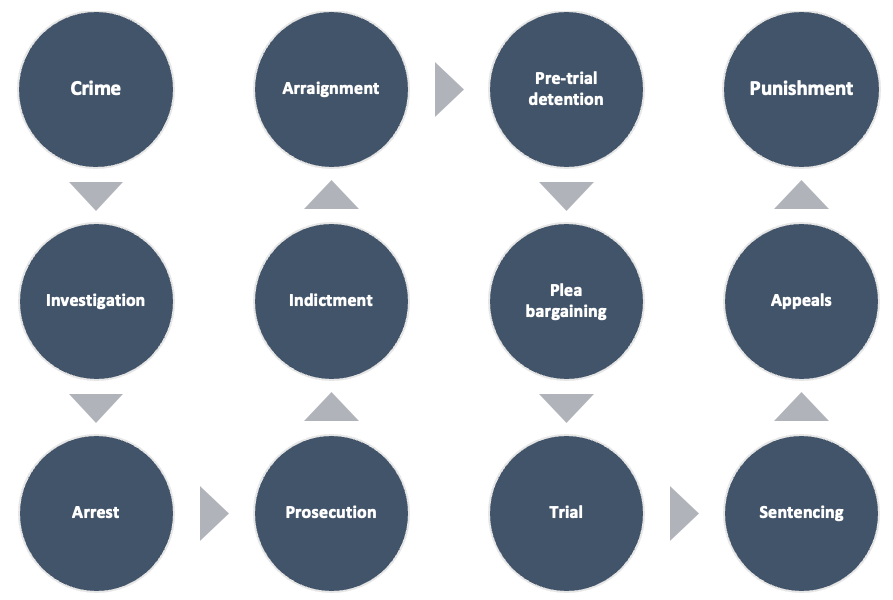

Chapter 3 explains how racialized systems of control have continued beyond the history discussed in the previous section and how they continue today with no sign of backing off. Further, Chapter 5 provides a thorough explanation of policing and the unequal treatment that is maintained from someone’s first contact with the criminal legal system. This includes arrest rates, racial profiling, over-policing in racial minority neighborhoods, biased practices, and misused discretion. For this reason, in this chapter, we will begin with what happens once someone has already been arrested and is formally brought into the criminal legal system. As you can see in Figure 7.10, the first two steps of the process (crime and investigation) have already been covered in other chapters. Let’s begin with what the experience is like once the arrested party arrives at jail.

Recognizance, Arraignment, Bail, and Bargaining

When an individual is arrested and brought into their local jail, there is an employee who is tasked with deciding whether that individual should be released on their recognizance (trusting them to leave the jail but later to return for their court date) or must be booked into the jail and held over for court. This is the first of these discretionary decisions post-arrest. The second is made at the arraignment, a court session in which people are formally told their criminal charges. At this point, the judge determines again whether the individual can be trusted to come back to court on their own and not do anything bad while they are out in the community pending trial or plea negotiations, or if they need to be held in jail while they wait through this process. The judge makes this decision by either assigning or denying them bail. Both of these keep-or-release decisions are important steps in the process, and both are determined by human beings with implicit biases they may or may not even realize they have.

First, there is the issue of trusting someone to return to court on their own and to be released on their recognizance. This begs the question of whose recognizance is trusted and whose is perceived as dubious. The Prison Policy Initiative (2019) confirms that of those held pretrial, 43 percent are Black and nearly 20 percent are Latinx. When we compare this to the general U.S. population, where only 12 percent of people are Black and 13 percent Latinx, there is a clear disparity of people of color being overrepresented among those denied their freedom despite being presumed innocent according to the law (Sawyer, 2019). In metropolitan areas, studies show that a Black person charged with a felony is over 25 percent more likely to be held while awaiting trial than if he were white (Sawyer, 2019).

Next, this is again a concern with the option of assigning bail versus having to await trial in jail. Scholars have examined these decisions in terms of the different amounts of bail assigned by the courts along racial lines. The Sentencing Project reports, “Blacks and Latinos are more likely than whites to be denied bail, to have a higher money bond set, and to be detained because they cannot pay their bond” (2018:Pretrial). In the United States, people of color charged with crimes are 10 percent to 25 percent more likely to be held awaiting trial or to have to pay cash bail compared to their white counterparts, and those bail amounts for people of color are two times as high as those of white people (Sawyer, 2019).

Judges are supposed to consider the flight risk and dangerousness of the person before them when determining whether to allow for bail and at what cost. Some states use risk assessments to determine who can be released pending trial, knowing that human discretion is faulty. Unfortunately, those assessments have also been found in multiple studies to be racially biased and inaccurate (Freeman et al., 2021; Human Rights Watch, 2018; NCSL, 2022).

If any of this seems harmless or just unfair at the start of things, that makes it even more important to understand the implications of being able to aid in one’s defense and the act of detaining people who are allegedly still presumed innocent under the law. Having to wait in jail pending trial punishes people before they have been convicted and makes their chance of being convicted significantly higher. “Pretrial detention has been shown to increase the odds of conviction, and people who are detained awaiting trial are also more likely to accept less favorable plea deals, to be sentenced to prison, and to receive longer sentences” (The Sentencing Project, 2018:Pretrial). The impact of these early decisions can be devastating for many people, particularly the poor and people of color.

Consider the circumstances of someone who is held in jail while awaiting their trial. They are at the mercy of their attorney in terms of aiding in their defense. They cannot easily call their attorney, and they will only meet with their lawyer when they come to the jail. Also, they cannot aid in their defense, meaning they cannot help put together witnesses or evidence or anything else that might help their case. Instead, they spend this time in jail, which is intentional and used as a bargaining tool by the prosecuting attorney. The more miserable someone is while awaiting trial in jail, the more likely they are to accept a plea deal, and, since they are vulnerable from their position in jail, they cannot bargain from a position of strength or confidence. It is for these reasons that people held over in jail while awaiting trial are more likely to accept less favorable plea bargains and receive longer sentences in prison (The Sentencing Project, 2018).

Plea Bargaining Strategies

The experience of being in jail makes defendants more open to accepting a deal and pleading guilty if it means they can move out of that setting. Even going to prison is better than staying in jail. For this reason, prosecutors often ask for outrageous bail amounts that they know people will not be able to meet. This is one of many subtle strategies used to get those they are prosecuting to accept plea deals and avoid going to trial. A plea bargain requires the accused to claim they are guilty and give up their rights to a trial or appeal. Instead, they go straight to their punishment and forfeit the right to ever appeal their conviction. In 98 percent of cases in U.S. courts, cases are settled through plea bargaining (Fair Trials, n.d.). This does not mean all of these people were, in fact, guilty of the crimes for which they pleaded. An estimated 20,000 people are in prison who pleaded guilty to specific crimes despite being innocent (Fair Trials, n.d.). The National Registry of Exonerations confirms that in 2022, 25 percent of exonerations (officially recognizing someone’s innocence despite their conviction and letting them go free) were for convictions from guilty pleas despite their innocence (NRE, 2023).

The statistics about plea bargains are far worse for people of color. “Implicit biases, or unconscious perceptions, can be especially detrimental for [B]lack individuals utilizing the plea bargaining process due to the prevalence of racial profiling stemming from stereotypes and misrepresentations of [B]lack criminality” (Knight, 2018:para. 2). The prosecutor is the one offering and negotiating the plea deal. That means if they see the accused as guilty (and we can presume they would not have charged them if they did not see them as guilty of the crime), they are more likely to require harsher punishments. Decades of research show this plays out time and again in plea bargain negotiations where the accused is a person of color. As scholar Anastasia Ferin Knight explains, “Existing stereotypes of [B]lack adults can support defense attorneys’ and prosecutors’ racial implicit biases, such that they may unconsciously view a [B]lack defendant as a threat regardless of the context of the case” (Knight, 2018:Effects of Implicit Bias on Plea Bargains). She further explains, “a racially biased prosecution lawyer may perceive a [B]lack defendant as more dangerous and their crime as more severe, making them more likely to offer a poor-quality plea that includes a criminal charge” (Knight, 2018:Effects of Implicit Bias on Plea Bargains).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4JbLd3PCp4

Check Your Knowledge

However, the prosecution is not the only party at fault or to blame. Defense attorneys show their implicit bias in the recommendations they make to their clients regarding plea negotiations. “Due to these implicit preferences for white defendants, [B]lack defendants are over three times more likely to be persuaded to accept a plea resulting in jail time” (Knight, 2018:Effects of Implicit Bias on Plea Bargains). That means their defense attorney is also nudging their clients of color toward harsher penalties compared to their white clients.

Researcher Carlos Berdejó (2018) examined over 48,000 plea deals to compare the initial charges filed at arraignment to the actual final convictions. He found that “white defendants are twenty-five percent more likely than [B]lack defendants to have their principal initial charge dropped or reduced to a lesser crime” (Berdejó, 2018:1187). He also found that initial felony charges were more likely to be reduced to misdemeanors for white defendants. In contrast, Black defendants with the same charges were more likely to end up with a felony conviction (Berdejó, 2018). Further, if the initial charges were for misdemeanor offenses, white defendants were more likely to get their charges dropped or face a penalty that held no incarceration (Berdejó, 2018). Also, for people with no previous criminal record, the courts had very little to go on to determine their risk of reoffending. Berdejó found in these cases that race became an even bigger factor, serving as the “proxy for a defendant’s latent criminality and likelihood to recidivate” (2018:1187).

Sentencing Disparities

This nation’s jails and prisons are filled with people serving out sentences they received through plea negotiations, parole revocation, or sentencing through the courts. When we look at the incarcerated population, we see a disproportionate representation of people of color. Common messaging would have us believe that the people who are incarcerated are the ones who should be, or they are the “bad” people who got caught and must be punished. That would mean people of color are overrepresented in jails and prisons because they deserve to be. We find time and again, however, that this is not true and is far from the complete picture of what is going on.

In a recent study examining prison populations over the last 20 years, the Council on Criminal Justice found that there has been a decline in arrests and prison admissions for Black people, yet they are given longer sentences compared to their white peers, so the racial disparity in prisons is growing (Sabol and Johnson, 2022). For example, while the prison sentences for white people convicted of drug and property crimes became shorter, the sentences for Black people convicted of the same crimes got longer (Sabol and Johnson, 2022). Sentences for violent crimes increased for both white and Black people, but the increase for Black people happened at nearly twice the rate of that for white people (Sabol and Johnson, 2022). This difference has been attributed to possible previous criminal records, risk assessment tools, or gang sentencing enhancements – all of which impact people of color far more than their white counterparts for all the reasons discussed in this chapter.

Scholar Cassia Spohn found that “racial minorities – and especially young [B]lack and Hispanic men – are substantially more likely than whites to be serving time in prison; they also face significantly higher odds than whites of receiving life sentences, life sentences without the possibility of parole, and the death penalty” (Spohn, 2017:171). The Sentencing Project (2018) reports that although one in seven people in prison is serving a life sentence, 63 percent are Black or Latinx. The statistics are similar for those serving shorter sentences for drug offenses, with 56 percent Black or Latinx (Sentencing Project, 2018). Consider that only 29 percent of the U.S. population is Black or Latinx, meaning this dramatic disparity requires explanation, and studies have consistently shown that explanation to be racism and racist systems of oppression.

Licenses and Attributions for Paths Through the Justice System: The Court System

Open Content, Original

“Paths Through the Justice System: The Court System” by Taryn VanderPyl, revised by Jessica René Peterson, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 7.10. “The path from crime to punishment through the criminal legal system” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 7.11. “America’s Guilty Plea Problem: Rodney Roberts” by innocenceproject is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a category of people grouped because they share inherited physical characteristics that are identifiable, such as skin color, hair texture, facial features, and stature

the unfair treatment of marginalized groups, resulting from the implementation of biases, and often reinforced by existing social processes that disadvantage racial minorities

when police use race or ethnicity as a primary or sole factor when choosing to engage with or take enforcement action against someone

when an arrested individual is released based on trust that they’ll return for their court date

court session in which people are formally told their criminal charges

widely held beliefs or assumptions about a group of people based on perceived characteristics.

cancelling probation and sending a person to jail for failure to follow probation conditions

a form of prejudice that refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about whole categories of people, and about individual members of those categories because of their perceived race and ethnicity.