1.3 Social Sciences and Systems of Power

Sociology of gender falls into the category of critical sociology. Critical sociology addresses power in sociological research, methods, and theory. Critical sociology proposes that society, and therefore, social sciences are embedded with systems of power. Systems of power are the interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society. Sexism, racism, and capitalism are a few systems of power we will explore in this text. We will take a deeper dive into systems of power in Chapter Four.

Critical sociologists consider how these systems of power influence sociology as a field, society as a whole, and the individual and shared experiences of people. Critical sociology helps us understand how theories and methods can rationalize or challenge inequality. For example, researchers can have a great deal more power in terms of institutional authority and resources than the people they are researching. Research that does not acknowledge how power is distributed in the research relationship can reproduce existing systems of power.

Participatory research practices, in which the subjects of research become active partners in research, can redistribute power between researchers and the people they are researching. This redistribution of power can interrupt unequal systems of power. Throughout this book, we will share many examples of critical research practice related to the sociology of gender.

It is important to keep in mind that rigorous critique produces sound science. We begin this section by considering the value of systematic scientific research. We will also consider a historical critique of the European scientific tradition. We will meet an early founder of sociology whose significant contributions to sociology were excluded from the story of sociology for more than a century, and we will consider how reflexive methods can help make power more visible.

Sociology as an Evidence-Based Discipline

How have you learned about the society you belong to? Common knowledge of social reality can come from at least five sources: personal experience, common sense, media, expert authorities, such as teachers, parents, and government officials, and, tradition. These are all valuable sources of understanding how the world works, but they may not be interpreted the same by all people. How do we know that the conclusions we draw from our own experiences are true for someone else? What if another person’s experience leads them to a different understanding? What if experts disagree? What if experts have a financial or social stake in what people think is true? How can we ever really know if something is true?

There is a common misconception that studying people, culture, and society is based only on experiences and opinions. Sociology is a scientific and evidence-based discipline, meaning that sociologists gather and interpret data to define and describe society. Like any other scientific field, sociology has strict codes of conduct, rigor, oversight of research, and validation of any statements made from research.

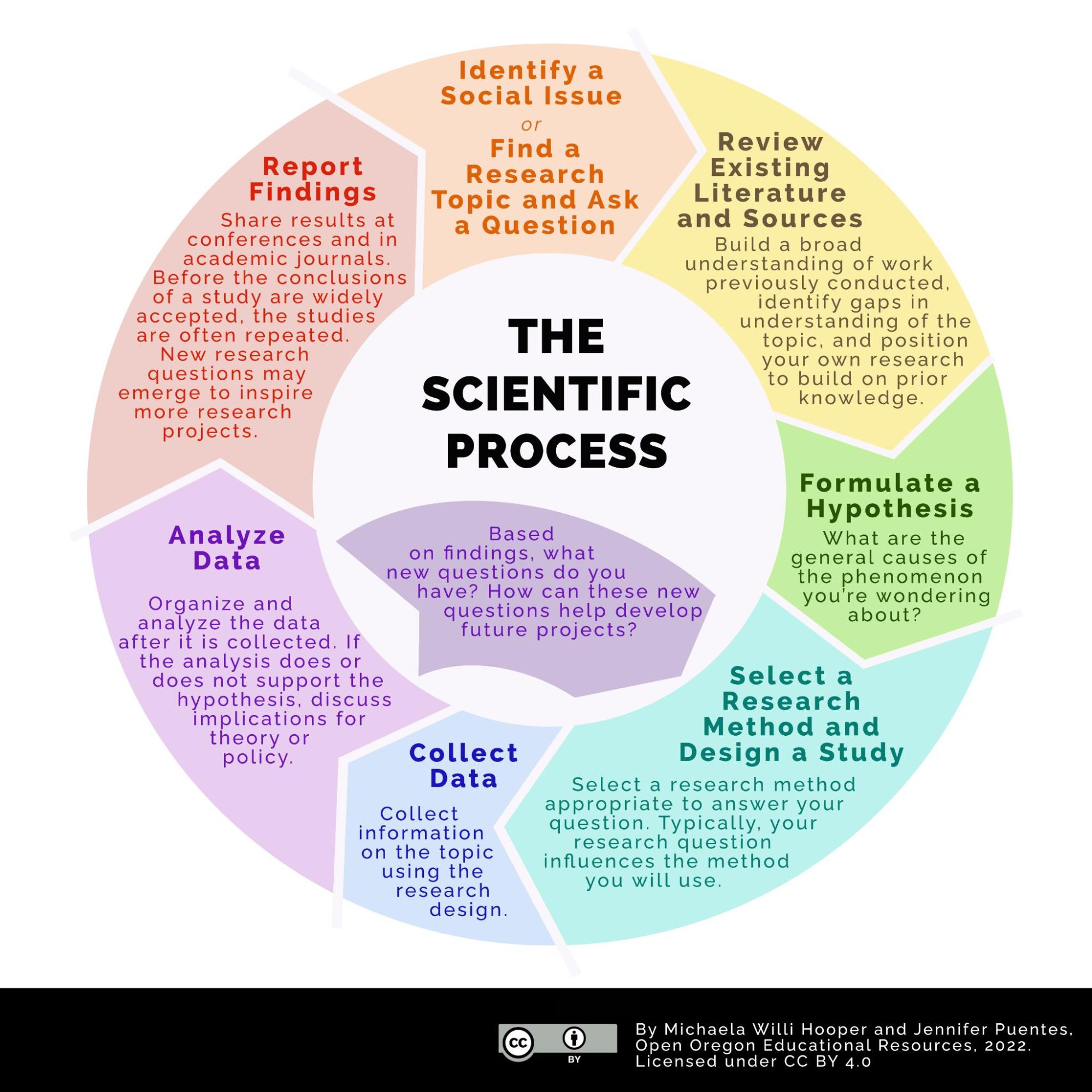

Research is a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence (figure 1.6). Research can be quantitative, using numbers to tell stories, or qualitative, turning stories into numbers.

In the previous section, we discussed both qualitative and quantitative examples of research. The census data about family composition came from quantitative research. Noelle Chelsley’s research on breadwinner moms is an example of qualitative research. Rigorous research is essential for a sociological understanding of people, social institutions, and society.

Sociology is a social science like anthropology, economics, political science, and psychology. All these disciplines analyze data from research to better understand how people think, behave, and organize their lives. When we say that sociology is a social science, we mean that it uses the tools of science, observation, questioning, research, evaluation, and validation to try to understand the many aspects of society. In this book, we will use examples of each of these tools to better understand gender.

An important goal is to yield generalizations, which are general statements regarding trends of social life. A generalization derived from research is that Black women have more maternal health complications in childbirth than White women (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024). A generalization is a statement of a tendency rather than a hard-and-fast law, but can suggest policy changes that can, for example, improve maternal health outcomes for Black women and by extension, all pregnant people.

Of course, generalizations do not apply to everybody because people are influenced but not totally determined by their social environment. That is the fascination and the frustration of sociology. No matter how much sociologists can predict people’s behavior, attitudes, and life chances, many people will not fit the predictions. These exceptions to generalizations are also important to sociologists. This is especially true of gender when so many of the generalizations that our society takes for granted do not match the lived experience of a significant portion of the population.

Critical research should also question the assumptions that can be hidden in generalizations and account for how social power influences those assumptions. High-quality, peer-reviewed research strives for objectivity but can not be totally neutral because research happens in institutions shaped by power. Therefore, critical sociology also questions the power structures of research institutions, asking whose perspective may have been overlooked or even suppressed. In the next section, we will examine the scientific process to identify some of the consequences of institutional bias in social sciences.

Critique of the Scientific Process

Social Sciences, including economics, psychology, political science, and sociology, emerged from the European “Age of Enlightenment.” During this period, spanning the 17th and 18th centuries, natural scientists in England and Europe identified and applied an objective, systematic, and reproducible scientific method, described in the previous section, which drove rapid advancements in physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, and medicine.

Until this time, Europeans primarily relied on religious institutions to explain human behavior and the proper ordering of society. Early European sociologists like Harriet Martineau (she/her, 1802 -1876) and Auguste Comte (he/him, 1798–1857) set out to define a more rational science of society. By applying rational scientific methods—questioning, observing, and testing hypotheses—to the study of society, early social scientists developed new ways to describe and theorize about human behavior and human society.

The European Enlightenment was inspired by indigenous intellectuals from European colonies and by ancient Greek philosophers and poets (Graeber and Wengrow 2023). This movement did a lot to advance rational scientific inquiry, but some of the science that was produced during the era was not always rational or unbiased. Scientific societies and universities excluded most women and non-European men and were financially supported by profits from brutal colonial enterprises in Asia, the Americas, and the African Continent.

Unacknowledged biases about human difference produced ethnocentric theories about racial hierarchy that falsely assumed the cultural, intellectual, and physical superiority of White men. These theories and practices reinforced existing systems of power, justified the marginalization of non-European civilizations, facilitated the continuing enslavement, exploitation, and extermination of non-European people, and fueled the global expansion of European colonization.

In this book, we use the term People of the Global Majority (PGM) (figure 1.7). This is an emerging term that refers to people who identify as Asian, Black, African, Indigenous, Latinx, and other racial and ethnic groups who are not White (Campbell-Stephens 2020). Critical scholarship by PGM, People who are LGBTQIA+, and women have thoroughly discredited these sexist and racist theories. However, the legacy of those theories is still present in terms of the persistent global marginalization of people who are not cisgender White men.

While the Enlightenment-era emphasis on a systematic rational inquiry led to significant advances in science, Europeans neither discovered nor invented science. Neither did the Ancient Greeks who inspired them. Clever and curious people have always engaged in forms of systematic rational inquiry. The ethnocentric biases of European scientists led to the exclusion, erasure, or appropriation of many scientific and philosophical ideas developed by technologically advanced societies in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Similarly, most women were excluded from European universities and scientific societies until the mid-20th century, and the contributions of the few who were able to do research were often minimized or suppressed.

For example, Martineau translated and edited Comte’s six-volume Course on Positive Philosophy (1842) from French to English. Her translation, The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte (1853) is credited with making Comte’s dense writing accessible to a broad audience and helped to establish him as a founder of sociology. She also published several important original texts that explored the conditions of women and argued for equality and the abolition of enslavement. Her original work was criticized by the powerful men who dominated social sciences in her time. After her death, her earlier writings were suppressed and forgotten. Her contribution to the field was reduced to that of Comte’s translator until feminist scholars in the late 20th century revived her work (figure 1.8).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CcvOgHCM198&t=217s

Reflexivity and Interpretive Frameworks

What are you biased about? Have you ever had someone point out a bias you weren’t aware of? Biases and blindspots are like opinions—we all have them. Biases are our prejudices. They can be benign, like a preference for cats, or deliberate and harmful, like a deeply held belief that a certain group of people cannot be trusted. Blindspots are biases that we aren’t conscious of and are sometimes called implicit biases. Most people agree that good science should be objective and unbiased, but how do we know if it is? How can we know that a researcher isn’t allowing bias to influence research?

Peer review is a process in which researchers evaluate one another’s work to assess the validity and quality of proposed or completed research. Peer review can be an important check on bias that comes after research is complete, but it is also important for a researcher to be engaged in self-reflection at the beginning of the research design process. Reflexivity is a practice of self-reflection to examine how personal biases, feelings, reactions, and motives influence research. Reflexivity does not necessarily eliminate personal biases, but it does make them more visible. When bias is made visible, its impact can be reduced. Reflexivity also takes the perspective of research participants into account, making power dynamics between researchers and research participants more visible. Reflexivity and reflexive research practices can interrupt bias in research design.

Interpretive frameworks are reflexive approaches to research that rely on detailed observation and produce findings that are more descriptive and qualitative. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore a topic. Direct observation, interaction with participants, and collecting stories, are examples of interpretive research. Interpretive research also includes participatory methods like Photo Voice, which invites research participants to document their lived experience (figure 1.9).

Participatory research allows research participants more power to describe and interpret their experiences, and to decide how research is used. Participatory interpretive methods can reduce bias, interrupt dominant power structures, and produce superior data. Look for other examples of participatory research as you work through this book.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kAszQx62XxE

In addition to defining and describing systems of power, the sociology of gender advances sociological theories, methods, and conclusions that illuminate and interrupt inequality and oppression, including recovering and amplifying the perspectives of people who have been excluded from sociology, both as researchers and as subjects of research. As you will see in the next section, critical sociologists in the tradition of Martineau have been describing a sociology of gender since its earliest theories.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Social Sciences and Systems of Power

Open Content, Original

“Social Sciences and Systems of Power” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

“Social Sciences and Systems of Power Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Sociology as an Evidence-Based Discipline” is adapted from:

- “Sociology as a Social Science” by the University of Minnesota, in Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- “Approaches to Sociological Research” by Jennifer Puentes, Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Adaptations by Nora Karena, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include remixing and editing for context.

“Reflexivity and Interpretive Frameworks” is adapted from “Approaches to Sociological Research” by Jennifer Puentes, Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Remixed and edited for context by Nora Karena.

Figure 1.6. “The Scientific Process” by Jennifer Puentes and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“People of the Global Majority” definition by Campbell-Stephens (2020) is included under fair use.

Figure 1.7. “GLOBAL MAJORITY- THIS VIDEO IS SO BEAUTIFUL” by Rosemary Campbell-Stephens is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 1.8. “Harriet Martineau and Sociology” by Learning the Social Sciences is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 1.9. “PhotoVoice” by SecGovGroup is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

applies the tools of sociology to explore how gender, including sexuality, gender expression, and identity, is socially constructed, imposed, enforced, reproduced, and negotiated.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

a complex competitive economic system of power in which limited resources are subject to private ownership and the accumulation of surplus is rewarded.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

describes people who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth.

a process in which researchers evaluate one another’s work to assess the validity and quality of proposed or completed research.

a practice of self-reflection to examine how personal biases, feelings, reactions, and motives influence research.