2.2 A Process, and a System, and a Social Institution

“Once a child’s gender is evident, others treat those in one gender differently from those in the other, and the children respond to the different treatment by feeling different and behaving differently. As soon as they can talk, they start to refer to themselves as members of their gender” – Judith Lorber (2009)

Think back to the first time you thought about your gender or noticed it. You can connect that here to the first time you told someone you were a boy or girl or referenced your “sister” or “brother.” Can you remember learning the rules of being a boy or a girl? What to wear, how to play, and what you might be and do when you grow up? Were you taught that boys must be tough and girls have to be tender? Perhaps your parents taught you not to be limited by traditional gender expectations and encouraged you to be a kind, sensitive boy or a powerful, assertive girl. These examples of social teaching and learning reveal how gender is socially constructed.

A social construct is a shared meaning created, accepted, and reproduced by social interactions between people within a society. Laws, customs, countries, races, religions, and even ideas about knowledge and “common sense” are examples of social constructs. A social construct has no inherent meaning or definition. It means what society agrees it means. The production, normalization, and reproduction of social constructs is a major function of culture. We know that socially constructed meanings are not objectively true because they change over time and across different cultures.

While all cultures differentiate between women and men—the norms, roles, and social expectations about how men and women are expected to properly express their gender are different in different cultures and have changed over time. Furthermore, many cultures also include third genders or more fluid gender norms, roles, and social expectations. Restricting gender to one of two categories constructs a gender binary. This deeply ingrained way of thinking results in the social acceptance of people who are cisgender, to the exclusion of those who don’t fit neatly into this category. Binary constructions of gender are common in patriarchal societies.

Social constructs are how humans create meaning in social contexts. Because social constructs result from a natural process, the meanings we create, reproduce, and normalize can seem objectively true and universal. However, socially constructed gender meanings and norms can vary over time and across cultures. Even though they are not objectively or universally true, social constructs are important aspects of social life and have real-life consequences for individuals and societies in terms of power, status, and social norms. In other words, social constructions are not true but they are real. Chapter Five will describe systems of power that are based on socially constructed gender.

Judith Lorber (she/her), a founding theorist of the social construction of gender, developed and taught some of the first courses on the sociology of gender. Her theory states that gender is a process that creates the social differences that define gender, a system of stratification that assigns power to different genders, and a structure or social institution in which individuals’ social life is organized around gender (Lorber 2010). This section breaks down what gender looks like as a process, a system of stratification, and a social institution.

Gender as a Process

LEARN MORE: Gender Expansive Parenting

Some parents choose to delay revealing their gender and allow time for a child to discover their own gender. To learn more, watch Raising a Gender-Neutral Child [Streaming Video].

Recall from Chapter One that socialization is the process of learning culture through social interactions. The social institutions that create and maintain normative expectations for behavior are called agents of socialization. Gender socialization relies on four major agents of socialization: family, schools, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behavior. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads us to believe that gender is real rather than a socially constructed identity.

Family is the first and most important agent of socialization because it is the center of a child’s life. Parents, siblings, guardians, and grandparents, plus members of an extended family, all teach a child what he, she, or they need to know through primary socialization. Sociologists recognize that race, ethnicity, social class, religion, education, and other societal factors also play an important role in socialization. For instance, there is evidence that some PGM families are more likely than White families to model an egalitarian gender role structure for their children (Johnson & Staples 2004).

Sociologists examine how families enact gender socialization, the process by which people learn the norms, stereotypes, roles, and scripts related to gender through direct instruction or by exposure and internalization. For example, a child who grows up in a two-parent household with a mother who stays at home and a father who acts as the breadwinner may internalize these gender roles, regardless of whether or not the family is directly teaching them. Likewise, if parents buy dolls for their daughters and toy trucks for their sons, the children will learn to value different things.

There is considerable evidence that parents socialize boys and girls differently. Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. Boys in many cultures typically have greater privileges, such as being allowed more autonomy and independence at an earlier age. Boys may be asked to take out the garbage or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness, while girls may be expected to fold laundry or perform duties that require neatness and care. Boys may be given fewer restrictions on appropriate clothing, dating habits, or curfew. Girls may be given more permission to step outside their prescribed gender roles in dress and play but limited by an expectation to be passive and nurturing, generally obedient, and to assume domestic responsibilities.

Gender assignment is the first step of gender socialization. In the mid-20th century, birth announcements with gender assignment phrasing like “It’s a boy!” became common. This is an example of the social aspect of gender assignment. The advent of ultrasound technology that can identify sex organs before birth has led to a new trend in gender assignment of assigning gender even before birth, called gender reveal parties.

These social events involve parents or families planning an activity that reveals the biological sex of an unborn child, thus socially assigning a gender to the unborn child. Some may pop a balloon to release pink or blue confetti, cut a cake that is pink or blue inside, or shoot off colored pink or blue fireworks. You might have seen a gender reveal on social media. Some gender reveals even make the news when something goes awry. One particularly unfortunate gender reveal included fireworks that started a massive fire.

Our initial gender identity is assigned or imposed based on our visible genitalia and anatomical or physiological markers described in the last section. Once a child is labeled biologically male or female, they are raised as a girl or boy. They are then socialized to their assigned gender.

Gender as a System of Stratification

Geologists also use the word “stratification” to describe the distinct vertical layers found in rock stratification in rocks, like the one pictured in figure 2.2, as a result of geological processes. Social stratification is a set of processes in which people are sorted or layered into ranked social categories based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and status. Sociologists use the term social stratification to describe a system of social standing. Social stratification refers to the social categorization of people into rankings based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and power. Typically, society’s layers, made of groups of people, represent the uneven distribution of society’s resources, with people with more resources as the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers. An individual or group’s place within a system of social stratification is called socioeconomic status (SES). SES can be influenced by their race, social class, religion, and other socially constructed categories or human differences, including gender. In other words, social stratification isn’t just a process of creating differences. It also attaches social status to those differences.

Most people in the United States indicate that they value equality, a belief that everyone has an equal chance at success. In other words, hard work and talent—not inherited wealth, prejudicial treatment, institutional racism, or societal values—should determine social mobility. This emphasis on choice, motivation, and self-effort perpetuates the American belief that people control their social standing. However, sociologists recognize social stratification as a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent.

While inequalities exist between individuals, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns. Sociologists look to see if individuals with similar backgrounds, group memberships, identities, and locations in the country share the same social stratification. No individual, rich or poor, can be blamed for social inequalities, but instead, all participate in a system where some rise and others fall. Most Americans believe that rising and falling are based on individual choices. But sociologists see how the structure of society affects a person’s social standing and, therefore, is created and supported by society.

Recall from Chapter One that global gender inequality is the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender. This is what Lorber meant when she theorized that gender is a system of social stratification. In patriarchal societies, the process of socially constructed gender, as described in the previous section, limits social possibilities for people socialized as feminine, as well as people who are excluded from the dominant gender binary. In doing so, this ensures that people with male sex traits and who are socialized as masculine have political, economic, educational, legal, and cultural advantages over women.

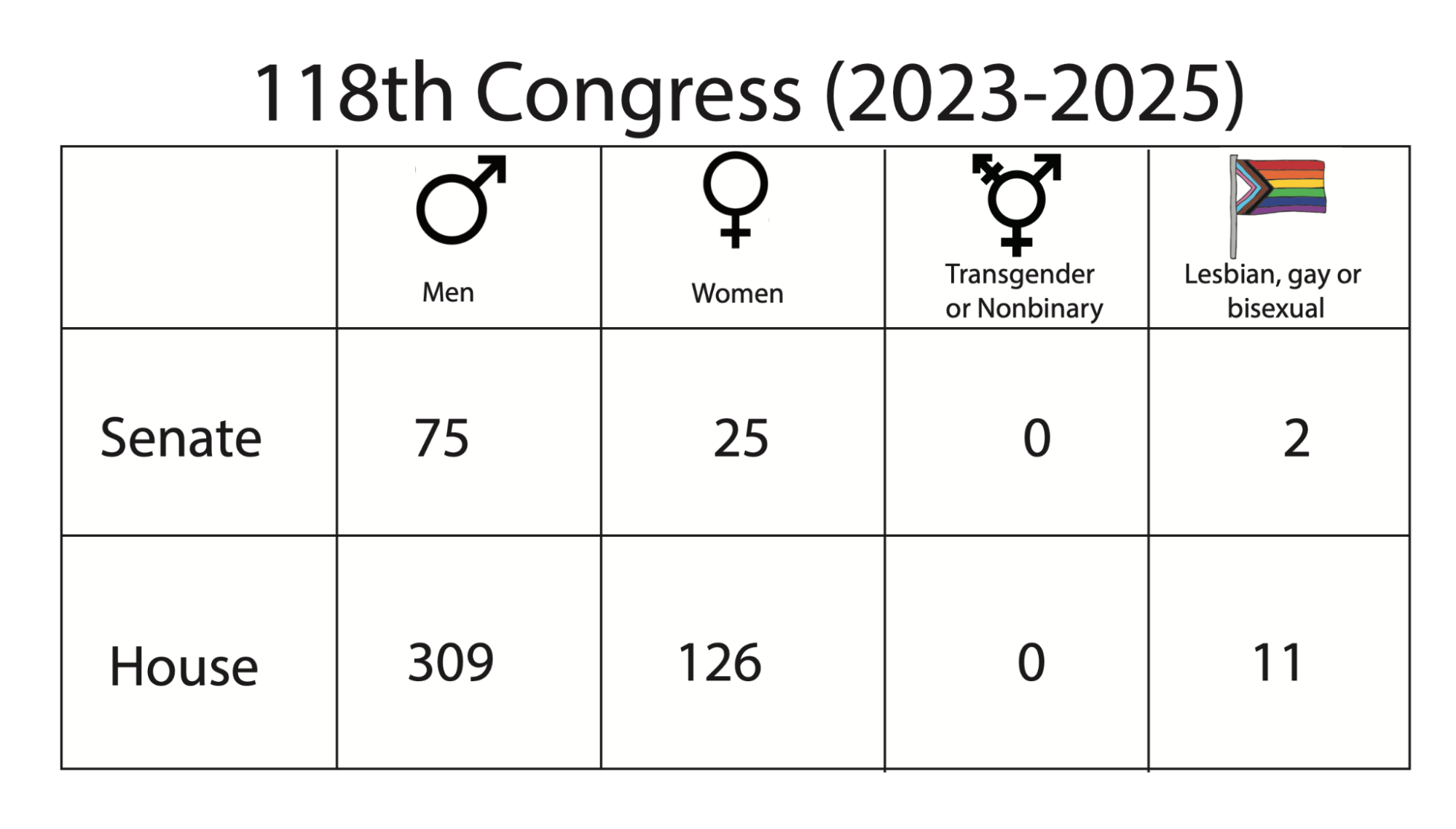

An example of the historical stratification of gender in the U.S. is the prohibition of voting for women voting until 1919. The political impact of denying political power to women is still impacting women today. Even though U.S. women have been legally allowed to vote for more than a hundred years, there has not yet been a woman president, and women are still not equally represented in state and national politics (figure 2.3). This unequal representation also translates into unequal laws that negatively impact the health and safety of women, as well as trans and nonbinary people.

Does equal representation in state and national legislatures produce laws that reduce gender inequality in society? The answer is yes. The National Women’s Law Center (NWLC 2020) reports that Women serving in legislatures with greater representation of women introduced and enacted more legislation than women serving in legislatures with lower levels of women’s representation, that the majority of women in state legislatures tend to be Democrats, who introduced more legislation about child care, sexual harassment, paid family leave, and minimum wage (National Women’s Law 2020).

Political stratification is just one aspect of gender stratification. Education, income, food security, health, and employment are also similarly stratified to favor men over women, trans and nonbinary people. Chapter Five will discuss the relationship between social stratification and unequal systems of power. Can you think of other aspects of society that are stratified by gender?

LEARN MORE: Gender Stratification

To learn more about gender stratification in families, education, employment, politics, and other aspects of society, watch Gender Stratification: Crash Course Sociology #32 [Streaming Video].

Pro Tip: Crash Course Sociology Videos are helpful overviews of key topics in sociology, but the presenter speaks really fast. Fortunately, YouTube allows users to slow down videos. Learn how to adjust playback speed here: Learn about features that help you control your viewing experience on YouTube [Streaming Video].

Gender as a Social Institution

The third function of gender that Lorber offered is gender as a social institution, in which individuals’ social lives are organized around gender. Recall from Chapter One that a social institution is a large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society. Recall from Chapter One that social institutions are large-scale social arrangements that are stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society. We can say that gender is a social institution because it also creates and maintains social order and is deeply embedded in all aspects of our social life.

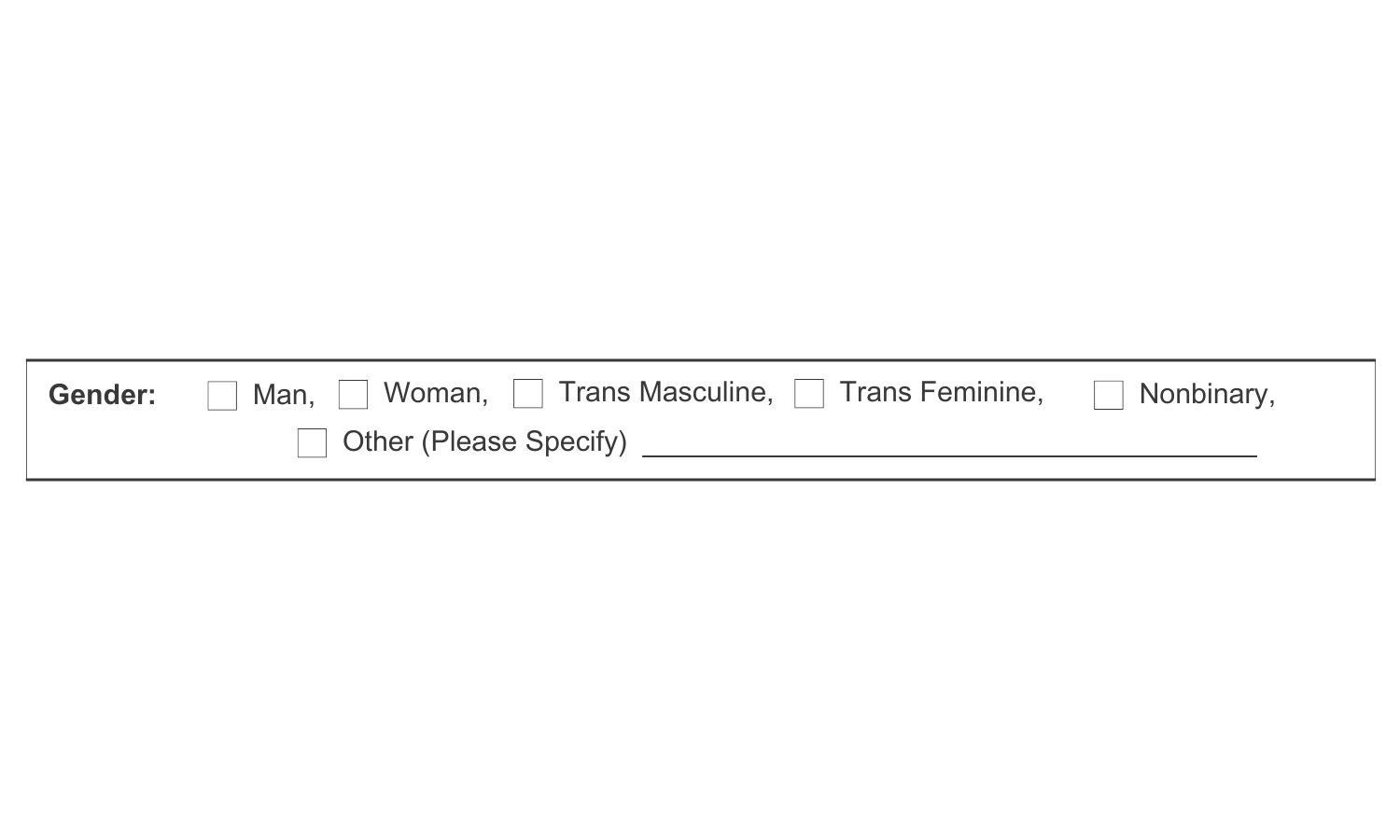

Nearly every application that we fill out asks us about our gender (figure 2.4). Sometimes, our gender is used simply as a marker of identification, but it is also used to determine our eligibility for certain services, educational programs, clubs, jobs, and resources. It can determine our role in our family, places of worship, and social groups. It determines our recreation, how entertainment and products are marketed to us, and even what bathrooms we can use. The gender assignment process we discussed earlier in this chapter determines how we fit into society.

Some sociological methods focus on examining social institutions over time or comparing them to social institutions in other parts of the world. In the United States, for example, there is a system of free public education but no universal healthcare program, which is not the case in many other affluent, democratic countries. Social institutions can be most visible when they break down. For example, for six days in January 2019, public school teachers in California went on strike. The Los Angeles school district (the second-largest in the nation) scrambled to provide substitute teachers and staff to stay with students after 30,000 teachers walked out, demanding smaller class sizes, more teachers and support staff, and a 6.5% raise. They eventually compromised with a 6% raise, more support staff, and a gradual reduction in class size, but the six days out of school cost the district over 125 million dollars.

How do breakdowns of social institutions like this one (public education) affect individuals? How does it affect students? Parents? Teachers and administrators? How would the strike affect other school employees, such as cafeteria workers or custodial staff? Our public education system meets many complex societal needs, including the training and preparation of future voters and workers. Still, on a more pragmatic level, it also provides a place for children to go while parents work.

Since the middle of the 20th century, we have seen remarkable changes in acceptable gender norms, growing resistance to an imposed gender binary, and increasing social acceptance of more expansive gender expression beyond the masculine/feminine binary. These can be understood as a breakdown of institutionalized gender and a reordering of society. It’s no surprise, then, that these changes are perceived as a threat to patriarchal society by people who benefit from the existing arrangements of social power.

Understanding gender as a socially constructed process, a socially constructed system of stratification, and a socially constructed social institution can help reduce anxiety around changing gender norms. Social constructs are flexible and adaptable to the needs of society and are always subject to change and adaptation over time and across cultures.

What about biological sex? Is it also socially constructed? In the next section, we will see that while the actual biology of the chromosomes and hormones that determine our sexual physiology are not social constructs, many of the meanings that cultures attach to them, including a false binary, are socially constructed as well.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for A Process, and a System, and a Social Institution

Open Content, Original

“A Process, and a System, and a Social Institution” by Nora Karena and Heidi Ebensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“A Process, and a System, and a Social Institution Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Gender as a Process” is adapted from “Agents of Socialization” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Heidi Esbensen and Nora Karena include revision for length and context.

“Gender as a System of Stratification” is adapted from “What is Social Stratification?” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena include revision for length and context.

Figure 2.2. “Strata in the Badlands” by Darrell Darwent is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.3. “Breakdown of Congressional Membership by Gender” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier, Oregon Open Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.4. “Check The Box” by Nora Karena and Mindy Khamvongsa, Oregon Open Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Gender Stratification: Crash Course Sociology #32” by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

shared meaning that is created, accepted, and reproduced by social interactions between people within a society.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

a limited system of gender classification in which gender can only be masculine or feminine. This way of thinking about gender is specific to certain cultures and is not culturally, historically, or biologically universal.

describes people who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth.

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

applies the tools of sociology to explore how gender, including sexuality, gender expression, and identity, is socially constructed, imposed, enforced, reproduced, and negotiated.

a large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society (Bell 2013).

the process of learning culture through social interactions.

social institutions that create and maintain normative expectations for behavior.

the process by which people learn the norms, stereotypes, roles, and scripts related to gender through direct instruction or by exposure and internalization.

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

a set of processes in which people are sorted, or layered, into ranked social categories based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and status.

the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender.

refers to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman/masculine or feminine.

the way our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation.