2.3 Sexual Differentiation

Reproduction in animals requires eggs, or ova, to be fertilized by semen, followed by a period of incubation to allow for sufficient physical development to allow the offspring to survive as it continues to mature. This can happen outside the body in birds, fish, and insects, while in mammals, it happens naturally inside the body. With the advent of reproductive technologies, like in vitro fertilization, an ovum can be fertilized outside of the body and then implanted into a uterus. Some animals, like female sharks, can reproduce asexually if there are no male sharks around to get the job done. Unlike sharks, humans cannot reproduce asexually. These reproductive functions, production of an ovum, fertilization of an ovum, and gestation of the fertilized ovum, usually require two different sets of reproductive organs.

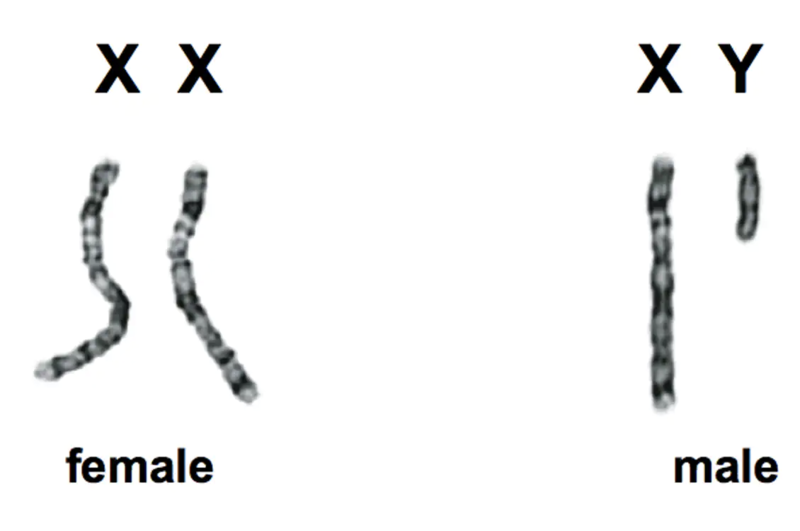

In the U.S. and many Western countries, we are socialized to assume that a person’s sex is based on the biological differences that determine these two reproductive functions of egg production and fertilization and that gender and sex are the same things. We are generally taught that females have two XX chromosomes, a uterus, ovaries, and vagina, and higher levels of the hormone estrogen. Conversely, males always only have XY chromosomes, a penis, testicles, and higher levels of androgens like testosterone. We are also socialized that people born with variations from this binary pattern must still be either male or female.

This chapter aims to distinguish between sex assigned at birth, as defined by reproductive biology, and socially constructed gender. Sex assigned at birth is the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes. The argument that sex assigned at birth and gender are the same thing is closely related to the argument that there can only be two sexes/genders. This section describes the biology of sexual differentiation in terms of physical markers of biological sex and the relationships between genetics, hormones, and physical traits. You will learn that, while it can be tempting to reduce reproductive biology to binary terms (i.e., either ovaries or testes), biological variation, an essential component in the evolution of all life, produces a spectrum of possible genetic, hormonal, and physical combinations.

The Chemistry Of Reproduction

Chromosomes are threadlike structures made of protein and a single DNA molecule that carry the genomic information from cell to cell (National Human Genome 2024). In plants and animals (including humans), chromosomes reside in the nucleus of cells. Humans have 22 pairs of numbered chromosomes (autosomes) and one pair of sex chromosomes, for a total of 46. Some babies at birth have two X chromosomes, and others have XY chromosomes, and these combinations are inherited from the father. At conception, each parent contributes a chromosome to the new zygote, which has the potential to develop into a fetus (figure 2.5). The male parent contributes either an X or Y chromosome to be combined with the female parent’s X chromosome (see figure 2.6).

XX chromosomes signal the development of ovaries, a vagina, and a uterus. XY chromosomes flood the developing zygote with hormones, and transform cells that would have developed into ovaries to become testes and cells that would have developed into a vagina to become a penis.

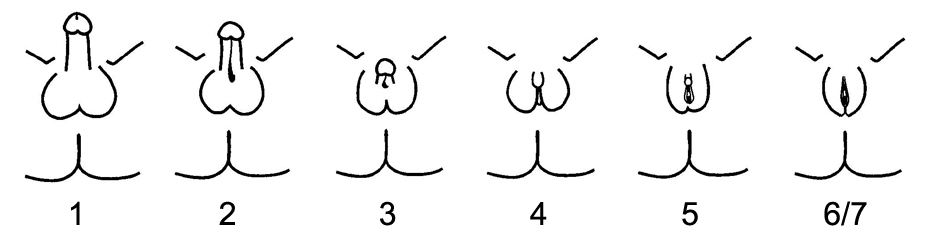

While most infants are born with either a penis or a vagina, these are not the only options. Rather, a spectrum of normal infant genitalia from “fully masculinized’’ to “fully feminized” is possible. Although these variations might be considered atypical, they occur in as many as 1 in 5000 live births. The “Quigley Scale” was developed by pediatric endocrinologist Charmian Quigley in 1995 to describe this range (figure 2.7).

Hormones that regulate sexual reproduction include estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. Everybody has all of these hormones, but people with XX chromosomes typically have higher estrogen and progesterone levels, whereas people with XY chromosomes have higher testosterone levels. However, many variations have been found across medical research.

Estrogen and progesterone support the development of female sex organs and physical traits during puberty, such as breast and uterus development, as well as fertility. Estrogen and progesterone levels can affect mood, emotions, brain function (such as focus and processing), and connection during and after childbirth to offspring.

Testosterone works similarly in men, assisting in the development of the penis and testes, regulating sex drive, bone mass, muscle development and strength, and production of sperm. Some studies show that testosterone affects social behavior. For example, aggressive or dominant behavior has been linked to higher testosterone levels (Dreher, et al. 2016).

When trans or nonbinary people take hormone blockers or hormone therapy, the treatment can prevent or assist in the development of secondary sex characteristics (facial hair, breasts, muscle tone, hips, etc.). Many studies show that these therapies have positive effects on transitioning individuals both physically and psychologically. These treatments shift the balance of the hormones for trans individuals, increasing testosterone in trans men or increasing estrogen and progesterone in trans women to support their gender identity. We will explore this more later, but it is important to understand how hormones affect the development of the sex traits humans are born with (primary sex traits) and those that develop after puberty (secondary sexual traits).

Sexual Variation

Since it is impossible to tell the sex of a baby or young child without inspecting their genitals, parents and caregivers routinely signal assigned gender with multiple visual and social cues like names, clothing, hairstyle or decorations, and color scheme (figure 2.4) (Lorber 2010). As children begin to mature sexually, they start to develop physical traits associated with femininity or masculinity. These are sexually dimorphic traits.

Sexually dimorphic traits are variations within a species, including secondary sex characteristics that indicate sexual differences but are not necessarily involved in reproduction. In other words, the physical characteristics that we generally associate with sex and gender include weight, muscle mass, facial and body hair, stature, and disease prevalence.

Here, too, there is broad variation. Sometimes, an individual can appear female, express themselves as female, use feminine pronouns, but also have masculine traits such as beard growth. The “bearded lady” of circus sideshows was a person with hirsutism, a dimorphic condition where women grow excessive body hair. This condition gained popular attention in early 19th century “freak shows” and circuses, making this either seem like a curse or a path to fame and money. Some of these women were also broad in the shoulders and much taller than other women of the time.

The existence of sex variations in animals, including humans, challenges the notion of biological sex as binary. A particularly striking sex variation, which has been observed in a variety of birds, insects, shellfish, and spiders, is Gynandromorphism (figure 2.9). Gynandromorphs appear to literally be half male and half female.

Gynandromorphism is a condition that is not found in humans, but people are born with differences in sexual development (DSD). DSD describes genetic, hormonal, or anatomical variations that produce atypical sex characteristics, including variations in chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals. People with DSD sometimes identify as intersex (Intersex Society of North America n.d.).

The bodies of people born with DSD do not fit strict binary definitions of male or female. Intersex, like female and male, is a socially constructed category that humans created to label bodies. The term marks biological variation among bodies. Several distinct biological sex variations are commonly observed in people born with DSD. For example, people with Klinefelter Syndrome possess one Y and more than one X chromosome. Does the presence of more than one X mean that the XXY person is female? Does the presence of a Y mean that the XXY person is male? They are neither chromosomally male nor female; they are chromosomally intersex. As noted previously, some people have genitalia that are not easily classified as fully male or fully female. So, why is this knowledge not commonly known?

Many individuals born with genitalia not easily classified as male or female are subject to genital surgeries during infancy, childhood, or adulthood. Infants with genital appendages smaller than 2.5 centimeters have routinely had their genitals reduced in size and been assigned female (Dreger 1998). In other words, surgeons literally construct and reconstruct individuals’ bodies to fit into the dominant binary sex/gender system.

While parents and doctors have justified this practice as “in the best interest of the child,” many people with DSD who experienced surgeries and arbitrary sex assignments, which they were too young to consent to, as traumatic. Some parents may not have all of the information or time to intervene in an infant surgery. Medical organizations, including the World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics, have called for deferring surgeries on children born with DSD until they are old enough to give informed consent (Mulkey et al. 2021).

Individuals often discover their chromosomal makeup, surgical records, or intersex status in their medical records as adults after years of physicians hiding this information from them. The surgeries do not necessarily make bodies appear “natural” due to scar tissue, disfigurement, or chronic infection. The surgeries can also result in psychological distress. In addition, many of these surgeries involve sterilization, potentially part of historical eugenics projects that aim to eliminate intersex people (Sparrow 2013). Therefore, a great deal of shame, secrecy, and betrayal surround these surgeries.

This is not a universal response to DSD conditions. Historically, individuals with DSD have been seen as special and celebrated in many cultures. Many religious traditions include deities that could be called intersex, transgender, or nonbinary. A notable example is the ancient Greek deity, Hermaphroditus (figure 2.10), who merged with a nymph so they could be together forever, shown in depictions as having both male and female attributes and mixed-sex characteristics.

The term “Hermaphrodite” has been used as a pseudo-scientific word for people born with DSD, but most people reject the label as derogatory. Around the world, people with DSD and their allies are advocating for full inclusion and acceptance beyond a rigid gender binary. You will learn more about third genders and other expansive gender identities and expressions in Chapter Four and Chapter Five.

Learn More: Sex Development and Best Interests

To learn more about DSD read “A Call to Update Standard of Care for Children With Differences in Sex Development” [Website] from the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics.

Common Social Constructs of Sex and Gender

When we say that sex and gender are socially constructed, we are also acknowledging that while many of the social constructs we have learned about sex and gender are not objectively true, they do have real consequences because society and culture are organized as if they are true. Let’s look at three common and harmful social constructs about sex and gender: sex as a single trait, sex as binary, and genitals as reliable indicators of gender.

The first social construct is that sex can be determined by a single trait., i.e. “All women have breasts, and no men have breasts.” As we’ve discussed, sex is the product of a combination of traits influenced by chromosomes, hormones, reproductive organs, genitals, and secondary sex traits like hair patterns, breasts, and body types. These highly variable traits exist in multiple combinations, and no one combination can definitively determine a person’s sex.

The second social construct is that sex is binary, i.e., “There are only two sexes.” The numerous possible variations in biological sex traits can result in a spectrum of sexes. A binary construction of sex presents a false choice that disregards and invalidates the lived experience of people who fall outside that oversimplified binary.

The third social construct is that genitals are reliable indicators of gender, i.e., “Everyone born with a penis is a boy.” There are many variations of biological sex, including chromosomal variations or biological variations. While genitals are a biological sex component, gender is a social construct. Reinforcing the idea that a penis makes one masculine and a vagina makes one feminine is harmful. We can see this damage in current events involving sports and schools. Laws in Ohio (2022) and New Jersey (2021) allow school staff and sports coaches to “check for genitals” on their students/players to decide if they can participate in gendered sports and on which team. For example, whether someone can participate in “girls’ basketball” (figure 2.11) can be based on a genital check that affirms they have a vagina. If they do not, they would not be able to participate in the sport. This is dangerous and harmful for many reasons, including the invasion of privacy and the potential for sexual assault.

So far, we have examined how socially constructed gender and sex are the result of social interactions that create shared meanings. We have also suggested that these meanings are not universal and can change over time and across cultures. Recall that a sociological perspective considers the impact of social factors on individual experience. Be sure to use your sociological imagination in the next section of this chapter to examine a fourth construction of gender: gender as a choice.

Real But Not True: Binary Sexual Differentiation

We take it for granted that the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences are based on objective fact, and that is, therefore, true. Throughout this book, we will use these puzzle pieces to draw attention to examples of the sociological imagination in action, sociological research, and sociological theories that demonstrate that gender is real in its consequences but not universally true.

The tools of sociology include:

- Sociological Imagination

- Research-based Evidence

- Social Theory

The biology of sexual differentiation has been empirically demonstrated to describe a spectrum of possible combinations of genetics, hormones, and physical characteristics.

We can recognize that socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences are not universally true when we can demonstrate that they:

- Change over time

- Are not the same in all societies

- Are imposed, enforced, reproduced, negotiated, or challenged through social interactions

Common social constructs related to sexual differentiation include:

- Sex can be determined based on a single trait., i.e., “All women have breasts, and no men have breasts.”

- Sex is binary, i.e., “There are only two sexes.”

- Genitals are reliable indicators of gender, i.e., “Everyone born with a penis is a boy.”

The real social consequences of binary gender differentiation include:

- People are routinely assigned a binary sex at birth.

- People with differences in sexual development have been assigned binary sex at birth to enforce the binary construction of sex. These people have historically been subject to many unnecessary surgeries and therapies that have been shown to do lasting physical and psychological harm.

- People whose gender identity (the gender they experience themselves to be) does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth experience gender dysphoria.

As you continue to work through this book, be on the lookout for other examples of socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences and for the ways that tools of sociology can be used to reveal them as social constructions that are not universally true, but have real consequences.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Sexual Differentiation

Open Content, Original

“Sexual Differentiation” by Heidi Ebensen and Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Real But Not True: Binary Sexual Differentiation” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.9. “Gynandromorphic Butterflies” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sexual Differentiation Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 2.4. “Check The Box” by Nora Karena and Mindy Khamvongsa, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.5. “Stages of Human Development” is adapted from “The development and the ways to rejuvenate cells – en” by Kaidor, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Modifications include cropping.

Figure 2.6. “XY Chromosomes” by Amanda CXZ is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.7. “Quigley scale for androgen insensitivity syndrome” by Jonathan Marcus is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 2.8. “Baby girl in swimsuit blue eyes with sunglasses” by Tammy Anthony Baker is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.9 A.“Gynandromorph of the common blue butterfly (Polyommatus icarus)” by Burkhard Hinnersmann is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 2.9 B. “Papilioandrogeusgynandromorph” by Notafly is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 2.10. Image by Levi Clancy is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

Figure 2.11. Image by planet_fox is licensed under the Pixabay License.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes.

people with differences in sexual development (DSD) sometimes identify as intersex.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

refers to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman/masculine or feminine.

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

variations within a species, including secondary sex characteristics, that indicate sexual differences but are not necessarily related to reproduction.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

a limited system of gender classification in which gender can only be masculine or feminine. This way of thinking about gender is specific to certain cultures and is not culturally, historically, or biologically universal.

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

shared meaning that is created, accepted, and reproduced by social interactions between people within a society.

a broad category of non-consensual sexual contact that includes various forms of rape and other illegal sexual contact.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)

a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender (APA 2022).