4.2 Early Theoretical Perspectives

During the mid-twentieth century in the United States, three dominant theoretical frameworks, or paradigms, emerged: structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. Each theory describes a way to think about how humans think and behave. As you will see, these frameworks draw on different combinations of the work of the classical theorists while attempting to explain social phenomena. Similar to the classical theorists, mid to late-20th-century American sociologists seldom questioned whose voices they included and whose voices they excluded.

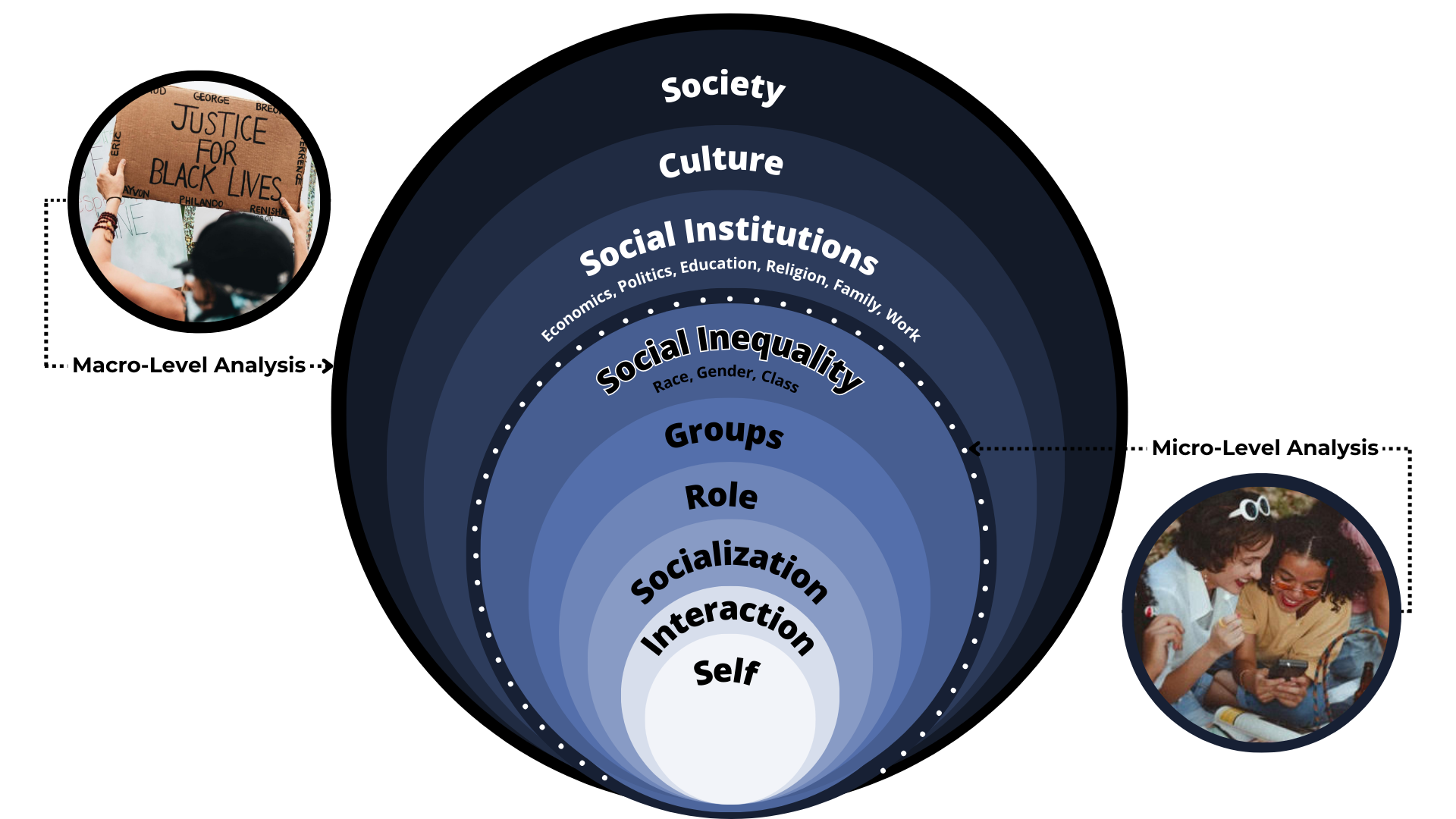

Sociologists use macro-level analysis and micro-level analysis to study different types of social groups and processes. Micro-sociology is the study of small groups and individual interactions. Macro-sociology studies how systems interact with individuals or with other systems. Figure 4.2 provides an overview of the levels of analysis in sociology, with examples of macro-level and micro-level analysis.

A macro-level research question might be, “How does the criminal justice system reproduce social inequality?” For example, Sarah Pemberton (she/her) examined gender-related policies and related outcomes for prison populations in the British criminal justice system, where comprehensive gender recognition legislation supports self-identification of binary gender categories and concludes that enforcement of these policies “…construct binary sex/gender identities while erasing the existence of transgender and intersex people, and these statistics also construct racialized identities” (Pemberton, 2013).

As you work through this section, try imagining that each theoretical perspective is a camera lens that zooms in with micro-level analysis or out with macro-level analysis to frame a topic like how we are socialized, why inequality exists, or the role of families in societies. Please resist the urge to choose one theory over another. Instead, ask yourself, “How does this theoretical framework help me understand specific aspects of social life differently?” and, “What new questions does this bring up for me?”

Structural Functionalism

One way to apply our sociological imagination to issues of gender is to ask questions about what gender does. Questions like, “What does gender contribute to society?” and “Is the gender binary a requirement for a stable society?” Structural functionalism, also called functionalism, is a macro-level theory concerned with large-scale processes and large-scale social systems that order, stabilize, and destabilize societies. It was the dominant theoretical framework in American sociology from the 1940s into the 1960s and 1970s. From the classical theorists you read about in the previous section, functionalist theorists drew from Emile Durkheim’s (he/him) (1858–1917) work and a rather narrow interpretation of Max Weber’s (he/him) (1865–1929).

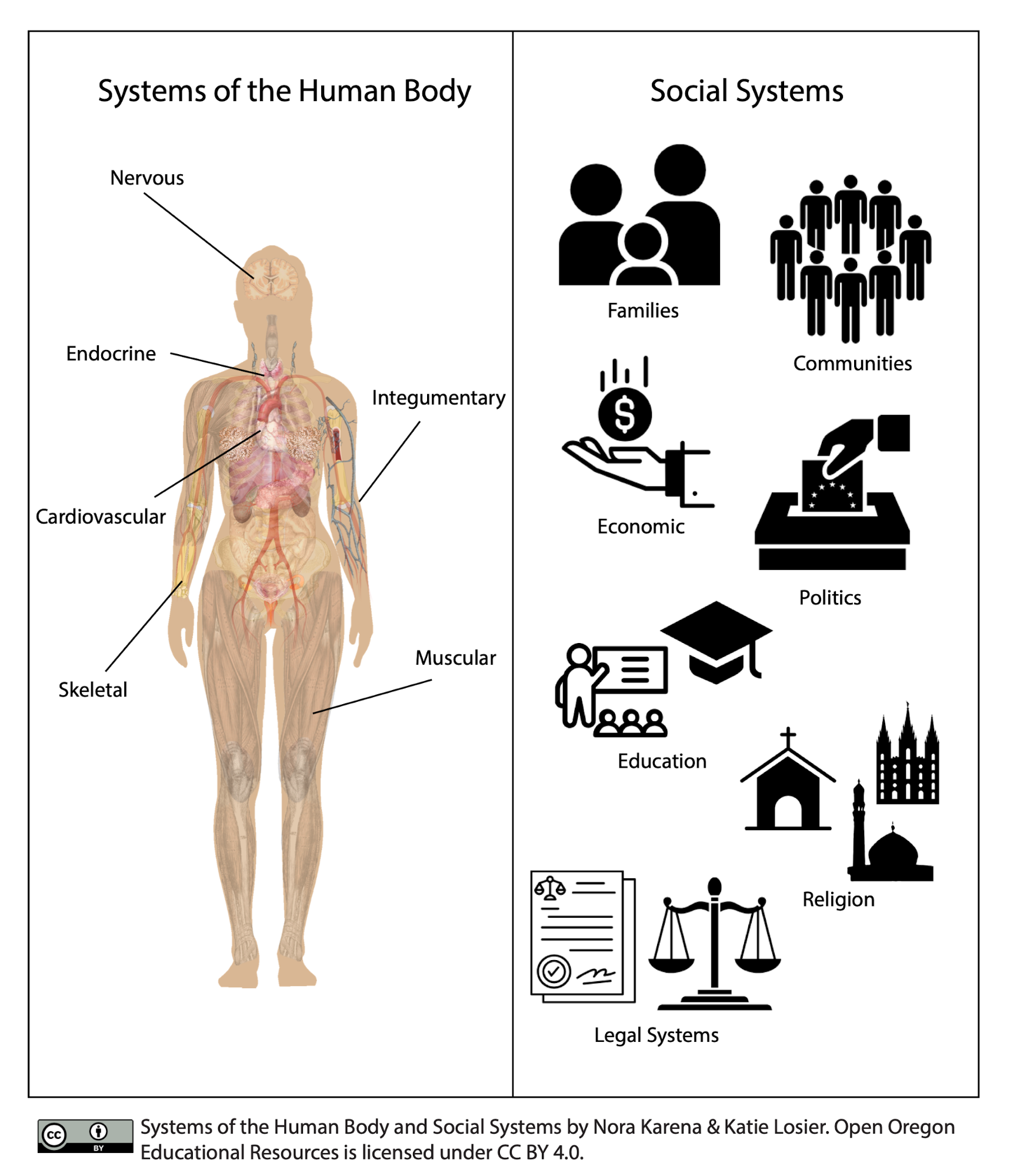

Functionalists proposed that society is a stable system made up of interrelated social systems, in the same way that a body is made up of interrelated biological systems (figure 4.3). Within this framework, social integration is important because that is how people come to feel connected within their society. As an example of social integration, think back to Durkheim’s discussion of the different types of solidarity. In modern societies, common rituals and shared values help people feel connected. Based on this framework, it may seem that societies are relatively stable and lack conflict. However, conflict can emerge when different institutions tell us to do different things. This can result in social strain and deviance.

A figurehead of functionalism, Talcott Parsons (he/him) (1902–1979) was concerned with the problem of order. He tended to think through problems and issues in an abstract and, at times, an unclear way. Robert Merton (he/him) (1910–2003), a student of Parsons and the functionalist tradition, broadened the concerns of functionalism by developing a unique blend of his teacher’s abstraction and data. He argued for theories that integrated abstract theorizing and empirical research. He saw exemplars of this in Durkheim’s theory of suicide and Weber’s arguments about the Protestant Ethic (Ritzer & Stepnisky 2022).

Structural functionalism has been heavily criticized within sociology. Some critics argue that functionalists present a rather static view of society that fails to account for social change. Others argue there are logical flaws within the framework. Specifically, critics argue that there is a problem with assuming that everything that persists in society has a function for that society. For example, does poverty or discrimination provide a function for society? Functionalism also has a hard time explaining inequality and, at its worst, may help justify existing inequalities.

Conflict Theory

Karl Marx (he/him) (1818–1883) was a social critic and philosopher from Germany who theorized that history could be divided into a series of distinctive periods or epochs based on the social relations and technologies available at the time. The main driver between epochs was class struggle (masters versus slaves, landlords versus serfs, owners versus workers). In each epoch, a revolutionary class would emerge and overthrow those in control, which would instigate the next epoch.

Conflict theory is a macro-level theory that proposes conflict is a basic fact of social life, which argues that the institutions of society benefit the powerful. It arose in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s against the backdrop of the rise of various social movements. It draws from Karl Marx and to some extent Max Weber and in doing so challenges functionalism. Some well-known conflict theorists include C. Wright Mills (he/him) (1916–1962), Ralf Dahrendorf (he/him) (1929–2009), and Randall Collins (he/him) (1941–).

In this framework, conflict and struggle are basic facts of social life. Groups with antagonistic interests are constantly struggling to maintain or change existing power arrangements. In the classical Marxist formulation, it is a struggle between owners and workers. Beyond class, it could include a struggle to maintain or dismantle masculine dominance and/or white racial dominance.

Gender conflict theory, inspired by Harriet Martineau (she/her) (1802–1876), was an important component of second-wave feminism, which is discussed in the next section. Race conflict theory was developed by W.E.B. Du Bois (he/him) (1886–1963), who researched the consequences of racism by documenting the lived experiences of people who were Black (Du Bois 2015). By taking account of inequalities based on gender, race, or class, conflict theory can help us understand who is benefiting and who is harmed by existing power arrangements.

Rather than seeing institutions as benign, conflict theorists argue the institutions of society promote the interests of the powerful while subverting the interests of the powerless. For example, consider how school funding is distributed. Schools in urban areas receive less financial support compared to their suburban counterparts. Those in suburban schools are given tools to get ahead, while those in urban schools are not (Kozol 2012). As a result, the students who go to well-funded schools have pathways into college and well-paying jobs. Students who attend schools with fewer resources face barriers that can make it hard to get ahead.

Conflict theorists argue these shared values and common rituals are ideologies that deceive people and make people comfortable with their position in society. The American Dream of working hard to get ahead is a dominant value in U.S. culture critiqued by conflict theorists. Conflict theorists argue that the opportunities to get ahead for most people are limited by artificial barriers in most institutions. According to conflict theorists, the mythology of the American Dream justifies the social position of those already who hold the most power in American society (Colomy 2010).

Conflict theorists claim that social equality cannot emerge from within the institutions but is driven by people organizing and mobilizing together to pressure the institutions of society. Labor unions that organize for better working conditions for working-class women and LGBTQIA+ people are an example of gendered class struggle (figure 4.4). Critics of conflict theory argue that it overemphasizes social change.

Symbolic Interactionist

We attach meanings to situations, roles, relationships, and things whenever we encounter them. For a symbolic interaction to occur, these meanings have to be shared and agreed upon by the people you are interacting with (figure 4.5). For example, if we attach the meaning of “family member” to someone, we will treat them as a family member or act based on the meaning of family member as we go about interacting with them. How we define family originates from interactions with others, such as parents, siblings, teachers, the media, and elsewhere. As we go about interacting with other people, we may come to modify our interpretations of what it means to be family, especially if the people we are interacting with have more inclusive or exclusive definitions of family.

Symbolic interactionist theory is a micro-level theory concerned with how meanings are constructed through interactions with others and is associated with the Chicago School of Sociology. Herbert Blumer (he/him), who coined the term symbolic interactionism in 1937 described symbolic interactionist theory as follows.

Humans act toward things on the basis of the meanings they ascribe to those things. The meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, the social interaction that one has with others and society. These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things he/she encounters. Blumer (2009)

Critics argue that symbolic interactionist theory has a hard time explaining macro-level phenomena. Other critics argue that it tends to downplay the importance of power, privilege, and oppression. Some present-day interactionists have tried to correct these problems by showing how symbolic interactionism can be used to explain power (Athens 2010) and organizational patterns (Hallett & Ventresca 2006). Within sociology, a separate professional association, the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction (SSSI), continues to debate symbolic interactionism.

Most contemporary sociology textbooks include feminism as a fourth foundational theoretical framework, but it can also be considered in relationship to functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. Feminism answers functionalism with calls for unjust social structures and unequal systems of power to be dismantled and replaced. Similarly, feminism answers conflict theory with calls for solidarity with people who are marginalized, especially those marginalized because of their gender and sexuality. Finally, feminism responds to symbolic interaction by demonstrating that gender norms are socially constructed in our everyday interactions.

The next section describes the development of feminism as multiple waves of interconnecting activism and scholarship that have expanded what is available to be taught, researched, and known about gender, sexuality, and social equality.

LEARN MORE: Major Theorists

To learn more about structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism, watch Major Sociological Paradigms: Crash Course Sociology #2 [Streaming Video].

Pro Tip: Crash Course Sociology Videos are awesome, but the presenters speak really fast. Review how to Speed up or slow down YouTube videos [Website] if you need to.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Early Theoretical Perspectives

Open Content, Original

Figure 4.2. “Levels of Analysis” by Nora Karena and Mindy Khamvongsa, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.3 “The Systems Of The Human Body And Social Systems” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Early Theoretical Perspectives Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Early Theoretical Perspectives” is adapted from “Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Matthew Gougherty, Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena include light edits and remixing for length and context.

“Macro-sociological” and “micro-sociological” definitions are adapted from “Levels of Analysis: Macro Level and Micro Level” by Jennifer Puentes in Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.4 “ILGWU workers meet Lyndon B. Johnson” by Kheel Center is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 4.5. “People Cleaning the House” by Annushka Ahuja is licensed under the Pexels License.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Major Sociological Paradigms: Crash Course Sociology #2” by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

also called functionalism, a macro-level theory concerned with large-scale processes and large-scale social systems that order, stabilize, and destabilize societies.

is a macro-level theory that proposes conflict is a basic fact of social life, which argues that the institutions of society benefit the powerful.

is the study of small groups and individual interactions.

studies how systems interact with individuals or with other systems.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

people with differences in sexual development (DSD) sometimes identify as intersex.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

a limited system of gender classification in which gender can only be masculine or feminine. This way of thinking about gender is specific to certain cultures and is not culturally, historically, or biologically universal.

purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal.

is an interdisciplinary approach to issues of equality and equity based on gender, gender expression, gender identity, sex, and sexuality as understood through social theories and political activism (Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.)

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

is a micro-level theory concerned with how meanings are constructed through interactions with others and is associated with the Chicago School of Sociology.

a right or immunity granted as a benefit, advantage, or favor. While privileges can be earned in some systems, privileges can also be unearned and based on social location. For the purpose of describing unequal power arrangements in systems of power we will be referring to those privileges that are “unearned advantages, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson, 2001).

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.