5.2 Gender in Unequal Systems of Power

Violence and coercion are not the only ways that binary gender norms and gender inequality are constructed in societies. They can also be constructed in public policy, laws, shared culture, and personal relationships. Violence, binary gender norms, and gender inequality exist because they work to establish and maintain arrangements of power. Why do they work? How do they work? Who do they work for? What other possibilities for creating a stable society might be created? An understanding of systems of power can help us answer these questions.

Systems of power are socially constructed beliefs, practices, and cultural norms that produce and normalize power arrangements in social institutions. For example, recall from Chapter One that patriarchy is a socially constructed system of power that normalizes power arrangements in families according to a gender-based hierarchy in which fathers maintain power over their intimate partners, children, and sometimes unpartnered siblings. In patriarchal societies, this heteronormative, hierarchical family structure is reproduced in religious, educational, and economic institutions to produce and normalize masculine dominance in society (figure 5.2).

This section describes how systems of power are socially constructed, four kinds of power, and how socially constructed intersectional identities determine individual access to power.

Four Domains of Power

The sci-fi film franchise The Matrix (Wachowski et al. 1999, 2003, 2003) is a fun action film that explores big ideas about power, gender, and the nature of reality. The series is set in a world where human beings are exploited as sources of power to feed a society of intelligent machines. These human batteries are not aware of their true condition because they are plugged into an artificial reality called “The Matrix.” A matrix is an interconnected structure that holds a system together or creates an environment. The matrix in the film is the artificially generated shared reality that humans experience. Another kind of matrix is the base of minerals from which crystals grow (figure 5.3). This idea of a matrix can also help us describe how systems of power are socially constructed.

The Matrix of Domination (figure 5.4) is a theoretical framework developed by Patricia Hill Collins (she/her) to describe how power is socially constructed. Hill Collins identifies four domains of socially constructed power, which arrange power and work together to create systems of power.

In Black Feminist Thought, Collins theorized that gender and other categories of identity exist within a complex Matrix of Domination, held together by four kinds of power, which Collins calls domains of power: structural power, disciplinary power, cultural or hegemonic power, and interpersonal power. Each domain is constructed by specific sources of power. For example, the structural domain of power is constructed with formal and informal organizational and institutional policies, laws, procedures, organizing principles, and leadership structures (Hill; Collins 1990).

| DOMAINS OF POWER | SOURCES OF POWER |

|---|---|

| Structural – The power to rule | Formal and informal organizational and institutional policies, laws, procedures, organizing principles, and leadership structures |

| Disciplinary – the power to punish and reward | Formal and informal organizational and institutional methods of policing and enforcement, disciplinary policies and procedures, and social structures |

| Hegemonic (Cultural) – the power to influence | Commonly held ideas, knowledge, values, customs, religion, folklore, social norms, art, literature, entertainment, popular and social media |

| Interpersonal – the power of self-determination | Social location (identity-based privilege and marginalization) Social status, internalized oppression, individual knowledge, lived experience, connectedness, autonomy, self-efficacy |

To better understand the domains and sources of power that maintain a Matrix of Domination, let’s return to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Have you ever wondered why survivors of IPV have a hard time getting away from their abusers? Have you ever known a survivor who couldn’t escape? Or did it take them a long time to be able to escape? A common question asked of people who are abused by an intimate partner is, “Why don’t you just leave?” Advocates and allies of survivors argue that this is the wrong question. Instead, we can ask, Why does an abusive person continue to harm their intimate partner? Or What are the structural and social barriers that keep someone from feeling like they can leave?

The reasons that abusive people can continue to abuse their partners can be identified as sources of power across the four domains of the matrix of domination). As we work our way through each domain, we will use the experiences of survivors of IPV to illustrate how power is constructed. We will also see how changes in each domain, in the form of changing policies, laws, culture, and interpersonal power, have changed some of the social norms around IPV and how much more remains to be changed.

Structural power is the power to rule. It is socially constructed with formal and informal institutional policies, laws, organizing principles, and leadership structures. Governments, religious institutions, business entities, and educational institutions are sites of structural power.

A long history of structural power has empowered people to use violence to control their intimate partners. Laws that explicitly grant men the right to hit their wives existed in Ancient Rome, in English Common Law, and in state and local laws in the U.S. These laws also have a long history of being contested. In 1882, Maryland was the first state to outlaw the practice. The first federal legislation that addressed IPV was the 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) (You learned about VAWA in Chapter Three). VAWA provides federal funding to states for legal and social services for survivors.

Yet despite VAWA and other legal prohibitions against IPV, many formal and informal social structures continue to keep survivors trapped in abusive relationships, including laws and policies that disadvantage single parents (i.e., lack of childcare, workplace policies that do not flex to meet the needs of people fleeing violence or single parents more generally). Permissive gun laws that allow abusers to keep firearms are another example of socially constructed power that normalizes IPV.

Disciplinary power is the power to punish and reward. It includes formal and informal methods of policing and enforcement, disciplinary policies and procedures, and social sanctions like shunning. Disciplinary power enforces existing power structures and regulates who has access to power. In addition to law enforcement and the legal system, disciplinary power is held by teachers, parents, and managers.

More than 60% of all arrests for interpersonal violence are IPV arrests, and only a third of all IPV arrests result in a prosecution (Communicating with Prisoners Collective, n.d.). An unintended consequence has been that victims also get arrested in high numbers, and in cases where police are uncertain about who committed the assault, they will arrest both people (Hirschel 2008; Dichter 2013).

Cultural power, also called hegemony, is the power to influence and persuade. Hegemony is the influence or the authority that one dominant social group holds over others. It is created and reinforced by a society’s commonly held ideas, knowledge, values, morals, customs, religion, folklore, social norms, art, literature, entertainment, popular media, and social media that work together to convince people to either buy into or resist existing power structures. Cultural power is also deeply embedded in our shared cultural history.

We have already identified some of the ways cultural power is socially constructed to normalize IPV, like rigid gender norms and the shared acceptance of aggression as a reasonable way to control people. Like structural power, cultural power can normalize IPV or make it a problem.

Interpersonal power refers to our sense of power or agency to control our lives and the power dynamics between individuals. Interpersonal power is constructed by social location (we will cover this in the next section), individual knowledge, personal biases, lived experience, and motivation. Our sense of personal motivation to change is impacted by our sense of connectedness, autonomy, self-efficacy, and personal agency (Deci and Ryan 1985).

Classically recognized expressions of IPV, like bullying, gaslighting, isolation, threats, and physical violence, all chip away at a survivor’s connectedness, autonomy, and self-efficacy. IPV and coercive control are effective because, over time, victims become isolated, and their sense of personal power begins to erode. Peer support groups are helpful for survivors to overcome isolation by finding support from other survivors, learning to recognize coercive power dynamics, and reconnecting with their sense of autonomy and personal power (Tutty et al. 2006).

Individuals can support survivors by helping them create interpersonal safety. This can include listening to and believing survivors, helping them develop a safety plan, and helping them locate material resources and social support. Even if someone doesn’t feel like they can get away yet, planning to do so in the future can help people prioritize safety and begin to find their power.

LEARN MORE: Safety Planning for IPV

To learn more about how to help people who are at risk for IPV, check out this interactive safety planning tool [Website].

Social Identity + Privilege or Marginalization = Social Location

How do you describe yourself? How do others describe you? Are you a working class feminine-presenting white cisgender lesbian student who loves skateboarding and country music? Or are you a middle-class Jewish transgender man with autism who manages a restaurant and collects old tools? Maybe you are a straight white cisgender man whose ancestors immigrated to the Oregon Coast from Sweden four generations ago and who hosts a weekly classic rock radio show and is passionate about social justice.

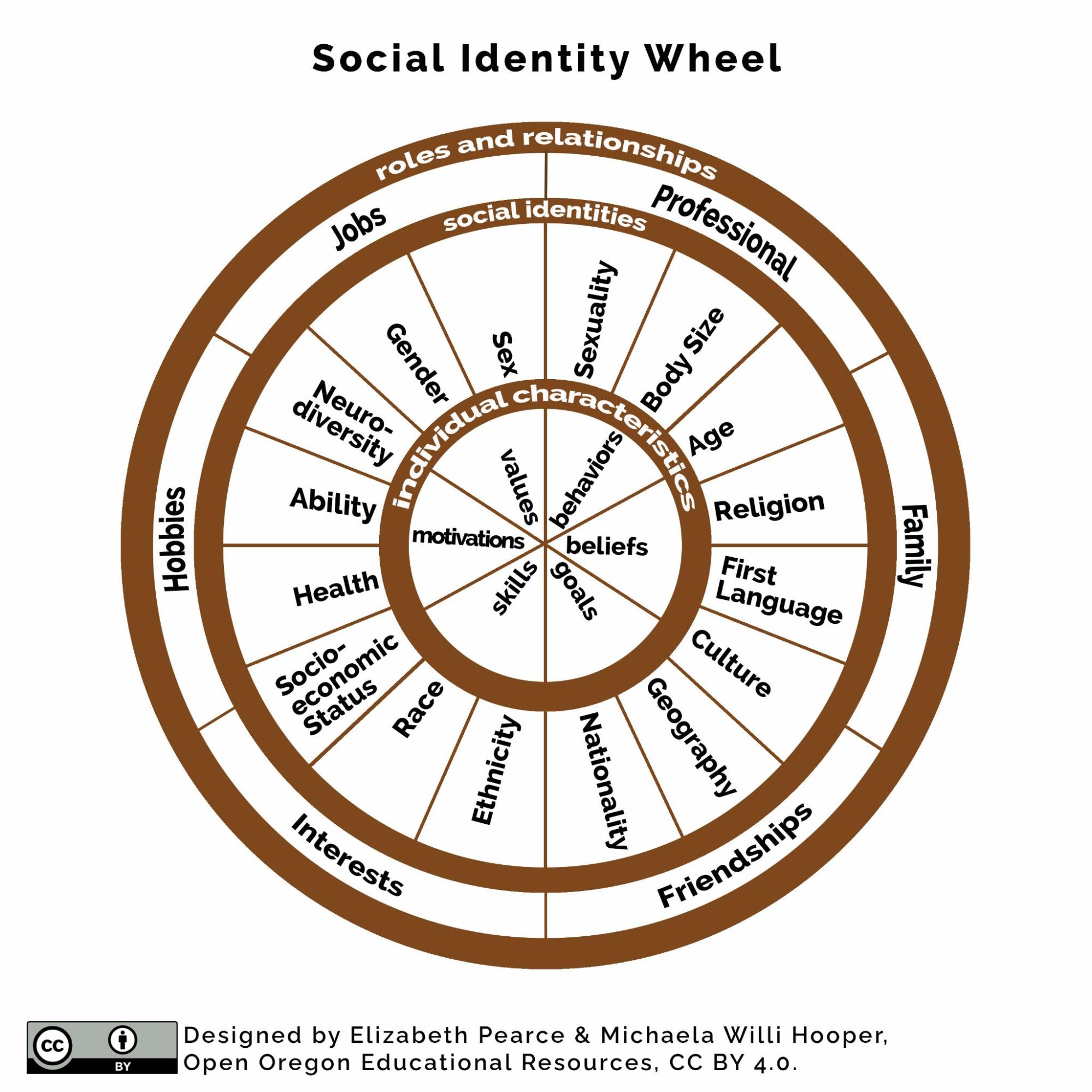

Each of us has a unique, complex personal identity. We also share individual aspects of our identity with other people, such as feminine-presenting people, people with autism, or people passionate about social justice. While our identities are individual and specific, each of the ways we describe ourselves that can be shared with others is also a social category or social identity (Figure 5.5).

Social identity consists of the combination of social characteristics, roles, and group memberships with which a person identifies. Social identity can be described as “the sum total of who we think we are in relation to other people and social systems” (Johnson 2014, p. 178). Our social identity includes:

- Social characteristics: These can be biologically determined and socially constructed and include sex, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, age, sexuality, nationality, first language, or religion, among other characteristics.

- Roles: These indicate the behaviors and patterns an individual utilizes, such as a parent, partner, sibling, employee, employer, etc., which may change over time.

- Group memberships: These are often related to social characteristics (e.g., a place of worship) and roles (e.g., a moms’ group), but could be more specialized as well, such as being a twin, a singer in a choir, or part of an emotional support group.

In unequal systems of power, some social identities, like lovers of country music or collectors of old tools, are relatively neutral. In contrast, others are consequential and associated with privilege or marginalization within a social system. We can tell when social identity determines power within a social system by identifying social inequalities. For example, 68% of LGBTQIA+ report feeling unsafe at school because of their gender identity or sexual orientation (GLSEN 2022). We know that gender identity and sexual orientation have a profound effect on how students experience school. Because we also know that bullying and peer victimization negatively impact educational outcomes (Ladd et. al. 2017), we can say that gender identity and sexual orientation are social identities that can determine whether people are privileged or marginalized in a social system.

Privilege is a right or immunity granted as a benefit, advantage, or favor. While privileges can be earned in some systems, privileges can also be unearned and based on social location. To describe unequal power arrangements in systems of power, we will be referring to those privileges that are “unearned advantages, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson 2001). The opposite of unearned social privilege is marginalization, a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday 2011).

Have you ever felt marginalized in a social setting? In general, people who are privileged in a social setting have an advantage that comes from an unspoken knowing that they belong and that they can be successful if they give their best effort. On the other hand, people who are marginalized in a social setting may feel like they have to prove their right to be there at all. It is common for people who have been marginalized to feel like the social environment was not created for them. Like social inequality, the existence of privilege and marginalization can be demonstrated in inequitable outcome disparities, such as 78% of LGBTQIA+ students reporting that they have avoided school functions or extracurricular activities (78.8%) because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable (GLSEN 2021).

Many people find it challenging to reconcile the idea that power is unfairly distributed in the U.S. with the idea that we are a “land of opportunity,” where each person has a shot at success no matter how they identify, and privilege must be earned by hard work and determination. But if privileges are deserved because they are earned, does that mean people who are marginalized who are marginalized deserve that status? And how do we account for people who hold privileged status because of the success of their parents, grandparents, or even distant ancestors?

This idea of a system of equal opportunities for success or failure is based on meritocracy. Meritocracy is a hypothetical system of power in which social status is determined by personal effort and merit. The concept of meritocracy is an ideal because no society has ever existed where social standing was based entirely on merit. Rather, multiple factors influence social standing, including processes like socialization and the realities of inequality within economic systems.

While a meritocracy has never existed, sociologists see aspects of meritocracies in modern societies when they study the role of academic and job performance and the systems in place for evaluating and rewarding achievement in these areas. Still, a true meritocracy can be hard to achieve when it exists within a larger system of unequal power arrangements.

It can be harder to see our privilege than it is to see our marginalization. This is because we are socialized not to see it. That, too, is a privilege (Johnson 2001). Because we value the idea of meritocracy, we are also socialized to feel guilty about having unearned privilege, especially as we begin to understand the harms experienced by people who are marginalized by the same systems of power that privilege us.

Those feelings of guilt are tricky because they can reinforce unequal systems of power by keeping us from acknowledging our unearned privilege. Discovering that we benefit from unearned privilege is nothing to be ashamed of, and it doesn’t mean we haven’t worked hard to earn other privileges. We don’t have to feel guilty. Instead, we can use our knowledge and power to be in solidarity with people who are marginalized to construct a more equitable and just system of power.

LEARN MORE: Privilege

Learn more about how unearned privilege works to sustain unequal systems of power in these books:

Privilege, power, and difference. Allan G. Johnson. (2001).

White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Robin J. DiAngelo. (2018).

And in this TED Talk from Peggy McIntosh: “How Studying Privilege Systems Can Strengthen Compassion” [Streaming Video].

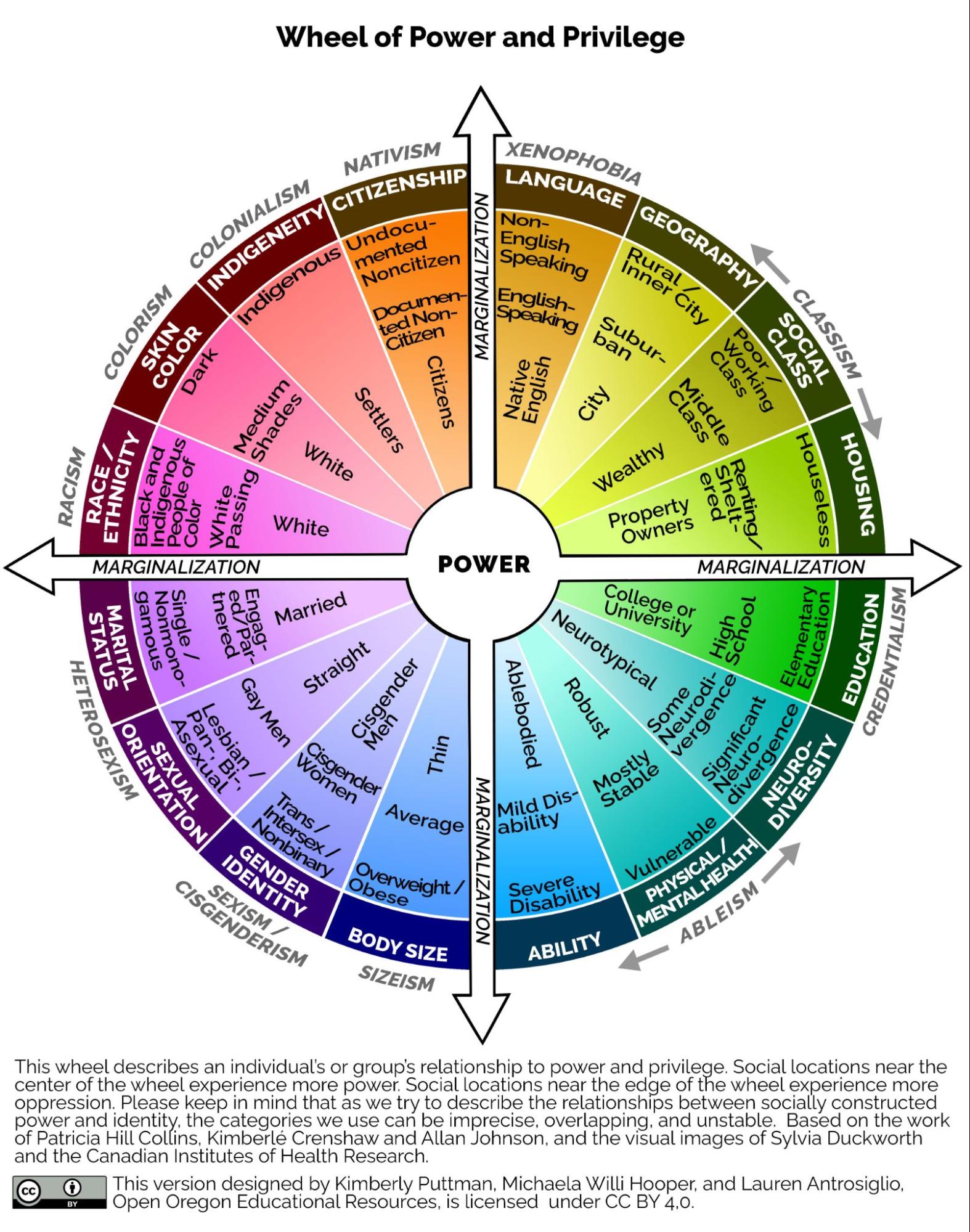

Aspects of social identity, like race, gender, or sexuality that are either privileged or marginalized in social systems determine our social location. Social location describes the relationship between social identity and social power. The Wheel of Power and Privilege (figure 5.6) uses social locations to demonstrate that gender identity and sexuality are two of many aspects of identity that are constructed to identify who is privileged or marginalized by systems of power in the U.S.

To read the Wheel of Power and Privilege, start with the word power at the center of the circle. Each socially constructed category of identity listed outside of the wheel determines how identity connects to power to produce marginalization or privilege within that system. People with characteristics near the center of the circle, such as White, non-disabled, property owners, have more privilege and, therefore, access to more social power. People in the center are also known as people in the dominant group. Non-dominant or marginalized groups are located toward the outside of the wheel. People in marginalized groups have less access to power.

Since all of us have multiple identities, we each navigate multiple systems of power with specific experiences of privilege and marginalization. In the next section, we will consider how multiple forms of privileges and marginalization can work together to situate people within complex social hierarchies (Hill; Collins 1990).

Intersectionality: Complex Hierarchies of Privilege and Marginalization

Social identity and social location are not just about who you are—they influence how much power you have in society. As we will see in this section, intersectionality is about more than describing diversity. Intersectionality is about power, which translates to wealth, health, and opportunity. Intersectionality shows us that socially constructed identities are also social constructions of power, which are organized into complex social hierarchies of power and domination.

Intersectionality describes how multiple social locations overlap and influence each other to create complex hierarchies of power and oppression and that overlapping social identities produce unique inequities that influence the lives of people and groups (Crenshaw 2015).

The term intersectionality was coined in 1989 by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (she/her) to describe how race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of social location are experienced simultaneously and how meanings of different social locations influence one another. Intersecting marginalization becomes its specific category, which we can only understand when we look at how cisgenderism, classism, and racism work together to make transgender people who are Black more vulnerable to sexual violence, poverty, and homelessness. Transgender people who are Black also report encountering barriers to seeking help legal, medical, and social services (United States Transgender Survey 2017). You can hear the actress Laverne Cox, who identifies as transgender and Black, share her intersectional analysis in figure 5.7.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-6ExSIoGU0

With intersectionality, Crenshaw exposed how gender and race have been historically divided into separate fields of study. Because of this division, “race” ends up referring to the experiences of men of color, the universal racial subject. Meanwhile, in studies of “gender,” White women are perceived as the universal female subject. However, we know that Black women have different experiences of discrimination and oppression than Black men or White women (Figure 5.8). Crenshaw writes, “Intersectionality is…a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power. Originally articulated on behalf of Black women, the term brought to light the invisibility of many constituents within groups that claim them as members but often fail to represent them” (Crenshaw 2015).

To better understand how your intersectional positionality shapes your experience of power, take another look at both the Wheel of Power and Privilege (figure 5.6) and the Matrix of Domination (figure 5.4). When you consider your intersecting social locations, can you identify some domains of power where you experience privilege or marginalization? Returning to the intersectional notion of coalitional politics from Chapter Four, how can you support, advocate for, or build solidarity with people who are marginalized where you are privileged (Oluo 2018)?

In the next section, we turn our attention to how intersectional systems of power impact individuals and how individuals respond to them.

Learn More: Intersectionality

To learn more about Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work to develop a legal framework based on intersectionality, check out her 2017 TED Talk, in which she applies intersectionality to police violence against Black Women: The urgency of intersectionality [Streaming Video].

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Gender in Unequal Systems of Power

Open Content, Original

“Gender in Unequal Systems of Power” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.8. “Intersectionality Graphic” by Mindy Khamvongsa, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Gender in Unequal Systems of Power Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Meritocracy” definition by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang from “9.1 What is Social Stratification“, Introduction to Sociology 3e, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The third paragraph of “Intersectionality: Complex Hierarchies of Privilege and Marginalization” is adapted from “Unpacking Oppression, Intersecting Justice: Acting Intersectionally” by Kimberly Puttman, “Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice“, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.3. “White and brown stone fragment photo” by J Yeo is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 5.5. “The Social Identity Wheel” by Elizabeth Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.6. “The Wheel of Power and Privilege” by Kimberly Puttman, Michaela Willi Hooper, and Lauren Antrosiglio, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Intersectionality” definition Crenshaw (1989) is included under fair use.

“Marginalization” definition by Chandler & Munday (2011) is included under fair use.

“Matrix of Domination” definition by Hill Collins (1990) is included under fair use.

“Privilege” definition by Johnson (2001) is included under fair use.

“Social identity” definition Johnson (2014) is included under fair use.

Figure 5.2. “Thanksgiving grace 1942” by Marjory Collins for the Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.4. “The Matrix of Domination” is adapted from Hill Collins (1990) by Nora Karena, Open Oregon Educational Resources, and is included under fair use.

Figure 5.7. “LAVERNE COX on Issues facing the Transgender Community | Bent Lens | In Conversation” by TIFF Originals is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender.

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

literally the rule of fathers. A patriarchal society is one where characteristics associated with masculinity signify more power and status than those associated with femininity.

a theoretical framework developed by Patricia Hill Collins (she/her) to describe how power is socially constructed. Hill Collins identifies four domains of socially constructed power, which arrange power and work together to create systems of power (Hill Collins, 1990).

describes the relationship between social identity and social power.

describes people who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth.

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

consists of the combination of social characteristics, roles, and group memberships with which a person identifies. Social identity can be described as “the sum total of who we think we are in relation to other people and social systems” (Johnson, 2014, p. 178).

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

a right or immunity granted as a benefit, advantage, or favor. While privileges can be earned in some systems, privileges can also be unearned and based on social location. For the purpose of describing unequal power arrangements in systems of power we will be referring to those privileges that are “unearned advantages, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson, 2001).

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people; often used to signify the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender identities to which a person is most attracted (Learning for Justice 2018).

a hypothetical system of power in which social status is determined by personal effort and merit. (Conerly, et al. 2021).

the process of learning culture through social interactions.

describes how multiple social locations overlap and influence each other to create complex hierarchies of power and oppression, and that overlapping social identities produce unique inequities that influence the lives of people and groups (Crenshaw, 1989).

any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion by any person, regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting (WHO 2022).

refers to political association with those who have differing identities, around shared experiences of oppression (Taylor, 2017).