2.5 Patterns and Process of Social Change

Aimee Samara Krouskop

In Chapter 1, we referred to social change as the ways that human interactions, behavior patterns, and cultural norms change over time. In other words, social change is the change in society created through social movements and external factors. Essentially, any disruptive shift in the status quo, be it intentional or random, human-caused or natural, can lead to social change.

Here, we’ll focus on institutions, culture, technology, modernization, population, and social conflict as drivers of social change. Alone or in combination, these drivers can disturb, improve, disrupt, or otherwise influence society. When we look at social change through the lens of society’s components, we can see reciprocal relationships. That is, each of these drivers of social change is also affected by social change in society.

Institutions as Drivers of Social Change

As we introduced previously, a main framework developed by functionalists is the concept of institutions. Researcher and author, Jim Woodhill, describes social change as “a complex dynamic of social structure and individual action.” He adds, “Institutions essentially create incentives, both positive and negative, for individuals and groups to act in particular ways. People behave either to reinforce or undermine an institution” (Woodhill 2008). When members of society determine that an institution no longer serves them well, they will undermine or create shifts in that institution.

Each change in a single social institution leads to changes in all social institutions. For example, once the U.S. economy became industrialized, there was no longer the same need for large families to produce enough manual labor to run a farm. Further, new job opportunities were in close proximity to urban centers where living space was at a premium. The result is that the average family size shrank significantly (figure 2.19).

This same shift toward industrial corporate entities also changed the way we view government involvement in the private sector, provided new political platforms, and even spurred new religions and new forms of worship. It has also informed the way we educate our children, as originally schools were set up to accommodate an agricultural calendar so children could be home to work in the fields in the summer. A shift in one area, such as industrialization, means an interconnected impact across social institutions.

Culture and Technology

Culture and technology are other sources of social change. Changes in culture can change technology. Changes in technology can transform culture. Changes in both can alter other aspects of society (Crowley and Heyer 2011). The car and the computer are two good examples, from either end of the 20th century, that illustrate the complex relationship among culture, technology, and society.

The car was still a new invention at the beginning of the 20th century. Automobiles slowly but surely grew in number, diversity, speed, and power. People built roads and highways. Pollution increased. Families began living farther from each other and from their workplaces. Tens of thousands of people started dying annually in car accidents. These are just a few of the effects of the invention of the car. The car altered the social and physical landscape of the United States and other industrial nations as few other inventions have.

The development of the personal computer has also had an enormous impact. Anyone old enough will remember having to type long manuscripts on a manual typewriter. They will easily say how computers have changed many aspects of our work lives.

E-mail, the internet, and smartphones have enabled instant communication and made the world a very small place. Tens of millions of people now use Facebook and other social media. A generation ago, students studying abroad or people working in the Peace Corps overseas would send a letter back home, and it would take up to two weeks or more to arrive. It would take another week or two to hear back from their parents. Now, even in low-income parts of the world, access to computers and smartphones lets us communicate instantly with people across the planet (figure 2.20).

As the world becomes a smaller place, it becomes possible for different cultures to have more contact with each other. This contact, too, leads to social change. Sometimes, one culture adopts some of the norms, values, and other aspects of another culture. For example, the rise of newspapers, the development of trains and railroads, and the invention of the telegraph, telephone, and later the radio and television allowed cultures in different parts of the world to communicate in ways not previously possible. Affordable jet transportation, cell phones, the internet, and other modern technology have taken such communication a gigantic step further.

Cultural lag is an important aspect of social change, a term popularized by sociologist William F. Ogburn (1922–1966). When one aspect of society or culture changes, this change often leads to or even forces a change in another aspect of society or culture. However, some time lapses before the latter change occurs. Cultural lag is the period of time between the introduction of new technological developments into a culture or society and the acceptance of the developments by institutions.

Discussions of examples of cultural lag often feature a technological change as the initial change. An example of cultural lag involves changes in child custody laws brought about by new reproductive technology. Developments in reproductive technology have allowed same-sex couples to have children conceived from a donated egg and/or donated sperm (figure 2.21).

If a same-sex couple later breaks up, it is not yet clear to all courts who should win custody of the couple’s child or children. Traditional custody law is based on the premise of a divorce of a married heterosexual couple who are both the biological parents of their children. Yet custody law is slowly evolving to recognize the parental rights of same-sex couples. Some cases from California illustrate this.

In 2005, the California Supreme Court issued rulings in several cases involving lesbian parents who ended their relationship. Generally, the court granted same-sex parents all the legal rights and responsibilities of heterosexual parents. The change in marital law that is slowly occurring because of changes in reproductive technology is another example of cultural lag. As the legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights said of the California cases, “Same-sex couples are now able to procreate and have children, and the law has to catch up with that reality” (Paulson and Wood 2005:1).

Modernization

Modernization is a complex set of changes taking place in societies that move from traditional to modern practices as their economies become industrialized. During this process, societies create a greater variety of more specialized institutions. For example, due to the creation of other specialized institutions, the family has lost some of its functions. Education and health systems, for example, now serve purposes that families used to provide. The modernization process also involves an increase in a society’s specialization of labor.

Sociologists debate about whether the modernization process is positive or negative for a society. Proponents of modernization claim that modern states are wealthier and more powerful and that their citizens are freer to enjoy a higher standard of living. They have produced scientific discoveries that have saved lives, extended lifespans, and made human existence much easier than imaginable in the distant and even recent past.

But the development of modern societies has also required the destruction of Indigenous cultures, polluted the environment, engaged in wars that have killed tens of millions, and built up nuclear arsenals that still threaten the planet. Modernization, then, is a double-edged sword. It has given us benefits, but it has also made human existence very precarious. We’ll discuss the modernization debate more in Chapter 4.

Population Growth and Composition

Populations are changing at every level of society. Births increase in one nation and decrease in another. Some families delay childbirth while others start bringing children into their folds early. Population changes can be due to random external forces, like an epidemic, or shifts in other social institutions. But regardless of why and how it happens, population trends have a tremendously interrelated impact on all other aspects of society.

In the United States, we are experiencing an increase in our senior population as Baby Boomers (people born from 1946 to 1964 during the postwar “baby boom”) retire, which will change how many of our social institutions are organized. For example, there is a massive shift in the need for elder care and assisted living facilities, and growing incidences of elder abuse. Retiring Boomers may also lead to labor or expertise shortages, and healthcare costs will become a larger portion of our economy.

Social Conflict: War and Protest

Social change also results from social conflict, including wars. The immediate impact that wars have on societies is obvious. For example, the deaths of countless numbers of soldiers and civilians over the ages have affected not only the lives of their loved ones but also the course of whole nations. The defeat of Germany in World War I led to a worsening economy during the next decade, which in turn helped fuel the rise of Hitler.

One of the many sad truisms of war is that its impact on society is greatest when a war between states takes place within the society’s boundaries. For example, the Iraq war that began in 2003 involved two countries more than any others: the United States and Iraq. Because it took place in Iraq, many more Iraqis than United States residents died or were wounded. The war affected Iraqi society, including its infrastructure, economy, natural resources, and so forth—far more than it affected the society of the United States. Most U.S. residents continued to live normal lives, whereas most Iraqis had to struggle to survive the many ravages of war.

War can change a nation’s political and economic structures. One example occurred during the American Civil War, when the deaths of so many soldiers left many wives and mothers without their family’s major breadwinner. Their poverty forced many of these women to turn to prostitution to earn an income, resulting in a rise in prostitution after the war (Marks 1990). Another example is when a winning nation forces a new political system and leadership on the losing nation.

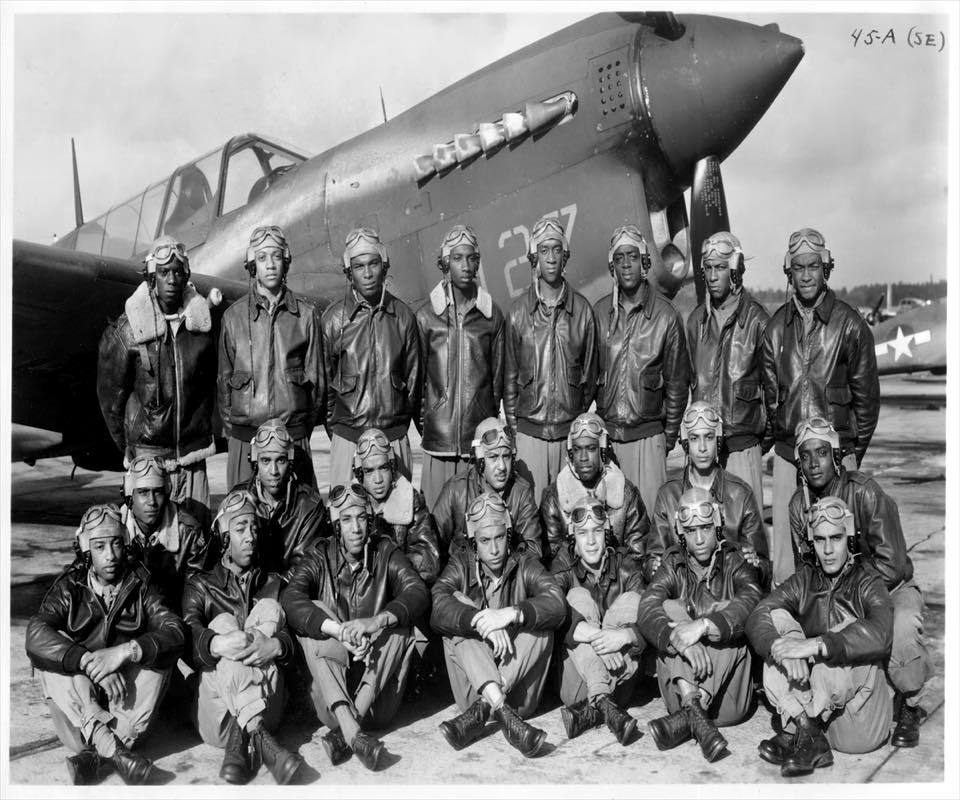

War can also shift racial and ethnic interactions. For example, the involvement of many African Americans in the U.S. armed forces during World War II helped begin racial desegregation of the military (figure 2.22). This change is widely credited with helping spur the hopes of African Americans in the South that racial desegregation would someday occur in their hometowns (McKeeby 2008).

Social Movements

Social movements mobilize large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem. These groups might be attempting to create change (such as Occupy Wall Street or the Arab Spring), resist change (such as the anti-globalization movement), or provide a political voice to those otherwise disenfranchised (such as civil rights movements). Social movements create social change.

While most of us learned about social movements in history classes, we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused—and we may be completely unfamiliar with the trend toward global social movements. But from the anti-tobacco movement, which has worked to outlaw smoking in public buildings and raise the cost of cigarettes, to uprisings throughout the Arab world, contemporary movements create social change on a global scale. We’ll discuss more about social movements in Chapter 10.

Licenses and Attributions for Patterns and Processes of Social Change

Open Content, Original

“Patterns and Process of Social Change” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Institutions as Drivers of Social Change” from “Reading: Social Change and Modernization” by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.19. The Haymakers by Théophile Deyrolle on WikimediaCommons is in the public domain (left). Untitled Painting ca. 1933–1943 is in the public domain. Courtesy of The Smithsonian (right).

“Culture and Technology” is adapted from “20.2 Sources of Social Change,” from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA, “Reading: Social Change and Modernization” by Lumen Learning, and “20.2 Sources of Social Change,” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include minor edits and addition of photo (figure 2.21).

Figure 2.20. “An Early Personal Computer, the Commodore PET” by the Department of Energy – Oakridge is in the public domain (left). “Apple” by Hernán Piñera on Flickr is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (right).

Figure 2.21. “A Couple in Thailand” by Prachatai on Flickr is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“Population Growth and Composition” is adapted from “Reading: Social Change and Modernization” by Lumen Learning, licensed under CC BY 4.0 and “20.2 Sources of Social Change” from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, abridged content and minor edits.

“Social Conflict: War and Protest” is adapted from “20.2 Sources of Social Change” from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, abridgment and minor edits.

Figure 2.22. “All African American 100th Pursuit Squadron” is in the public domain. Courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service.

“Social Movements” is adapted from sections of “Chapter 21 Social Movements and Social Change” in Introduction to Sociology: 1st Canadian Edition, by William Little and Ron McGivern, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, include reorganization and abridgement.

transformations in human interactions and relationships that transform cultural and social institutions.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

a complex set of changes that take place in societies that move from traditional to modern practices as their economies become industrialized.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the period of time between the introduction of new technological developments into a culture or society and the acceptance of the developments by institutions.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.