5.6 New Perspectives and Movements for Global Change

Aimee Samara Krouskop and Ben Cushing

Many scientists, development professionals, and global activists have been applying what we learned from the decades of aid and development. But there remains significant tension against the priorities of many development organizations and global economic institutions. For example, many continue to learn from the downfalls of the Green Revolution. They acknowledge that such an exclusive focus on technology to address the complex intersections of poverty, farming, food, and management of natural resources is problematic. However, many of these methods continue today.

During the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit, a powerful counter-mobilization effort was led by farmers and scientists, as well as civil society groups allied with Indigenous communities and small-scale food producers across the world. They voiced their concerns that leaders were framing our problems of food systems with such a focus on biotechnological interventions (Montenegro 2021). Let’s look at some perspectives that have emerged from these observations, as well as some movements arising from these tensions.

The Social Construction of Development

A good way to start examining the perspectives that are shifting in relation to foreign assistance, humanitarian aid, and development is to examine the assumptions and meanings we make. For generations, general knowledge in the United States has been that we live a healthier and more enjoyable existence than those of countries less prosperous than us. But, when we look closer, to what extent is this really true?

The United States has very high income and wealth inequalities. According to research conducted by the Pew Trust in 2019, public opinions of the economy are mixed. Those who report that the United States is in excellent or good economic condition are, by a majority, of the upper- and middle-income classes. Most of the people polled say the economy is only fair or poor. Their research also reveals some key experiences:

Two-thirds of lower-income adults (65%) say they worry almost daily about paying their bills, compared with about one-third of middle-income Americans (35%) and a small share of upper-income Americans (14%). The cost of healthcare is also a worry that weighs on the minds of many Americans, particularly those in the lower-income tier.

More than half of lower-income adults (55%) say they frequently worry about the cost of health care for themselves and their families; fewer middle-income (37%) and upper-income Americans (18%) share this worry (Igielnik and Parker 2019).

Indeed, 11.6 percent, or nearly 38 million people, in the United States live below the poverty line (Creamer et al. 2022). In 2023, the United States ranked 63rd in the world in life expectancy, sitting in the bottom rankings among the most high-income countries (“Data Page: Life Expectancy, aged 0” 2024). Finally, while the United States leads spending on health care around the world, 25.6 million residents were uninsured in 2022 (Tolbert et al. 2023). A multitude of NGOs work to fill in the gaps (figure 5.14).

The Social Progress Imperative is a global nonprofit that provides data on the social and environmental health of societies within and between countries. Their 2022 report shows that despite the United States scoring near the top for many economic indicators, its wealth and high levels of income do not translate into advancing levels of social development:

Since 2011, the United States has been declining in six of the 12 components, including Personal Rights …where it’s ranked 46th in the world and 33rd in Inclusiveness .…The steepest declines happened in the past 5 years. We also see stagnation in Nutrition and Basic Medical Care, Health and Wellness and a decline in Access to Basic Knowledge… (Green and Harmacek et al. 2022:1).

It seems that in the United States, we have lived with the notion that our lives are healthier and more enjoyable than in other countries, but in many ways, this is not true. What does this mean for global inequality, aid, and development?

The book of essays, The Development Dictionary, critically examined ideologies related to development by looking at the social construction of terminology applied to the industry. For example, Majid Rahnema writes that our general notion of poverty was created as a result of our societies becoming monetized and our global economy becoming based on export and import. After monetization, “…the poor were defined as lacking what the rich could have in terms of money and possessions” (Sachs 2009:175). This is important, Rahnema adds, because it frames the poor exclusively with a lens of lack or deficit. He poses some important questions:

…[W]hen poor is defined as lacking a number of things necessary to life, the questions could be asked: What is necessary and for whom? And who is qualified to define all that? …Everyone may think of themselves as poor when it is the television set in the mud hut which defines the necessities of life, often in terms of the wildest and fanciest consumers appearing on the screen (Sachs 2009:175).

The social construction of poverty (what it means to be poor) and its opposite, well-being (what it means to be well), have been more globally defined by rich countries like the United States. And that definition weighs heavily on whether or not a county’s citizens have money and possessions. The powerful influence of this social construction is even more evident when we see that, in many ways, our health and well-being rankings are not what we think they are.

The Dominance of Development

The way we socially construct development has consequences that can be seen in the actions of the development industry. The larger and more powerful development agencies, such as the World Bank and USAID, export the practical, economic, and cultural experience of the West to low-income countries. They do this by heavily relying on the economic measurements we introduced in Chapter 4 (such as GDP and GNI) to measure progress and prosperity. But, as we explored in Chapter 4, those indicators provide only a limited view of the human experience.

Equally important is when economic development interventions reinforce the hierarchy of nations. That is, development projects can bolster the positions of rich or core countries so that poor or peripheral countries remain dependent upon them. For example, the strategy of importing genetically modified crops and other technologies, providing loans in exchange for structural adjustment, and overall strategies that focus on purely global economic indicators hold in their roots a colonialist model that relies on the theft of Indigenous land and the exploitation of farmers’ and food workers’ labor. For some, this evaluation, solely based on a country’s capacity to produce, is part of a predatory and dominant perspective. However, this dominance is becoming more commonly acknowledged.

After the Green Revolution

In the report “Global Development Disrupted,” 93 leaders share a list of new initiatives and directions in international development they are most excited about. They include:

- A focus on inclusion and inclusive growth rather than just poverty…

- Nonviolent civic action…

- More focus on climate change and sustainable business practices…

- More focus on holistic efforts to address climate and energy issues…

- …Giving communities more choice and voice in program design (Ingram and Lord 2019:34).

Those leaders also explained that they see a trend toward localization in the development industry. More specifically, they see that local governments, local civil society organizations, and private companies will play increasingly important roles in addressing needs in receiving nations.

Most strikingly, some leaders are witnessing a decline in development. They say the distinction between “developing” and “developed” is narrowing as countries of all income levels experience similar social, economic, political, and environmental problems. Global issues such as migration, conflict, climate change, inequality, polarization, marginalization, and corruption are becoming common to more nations, and we need to find solutions as a global community to address them (Ingram and Lord 2019).

We’re also seeing this change in perspective and strategy outside of the traditional development industry. Generally, there is a greater emphasis on initiatives that directly provide the poor with what they need to improve their lives on their own. For example, providing microloans has become a popular model to help people who have no means of supporting themselves.

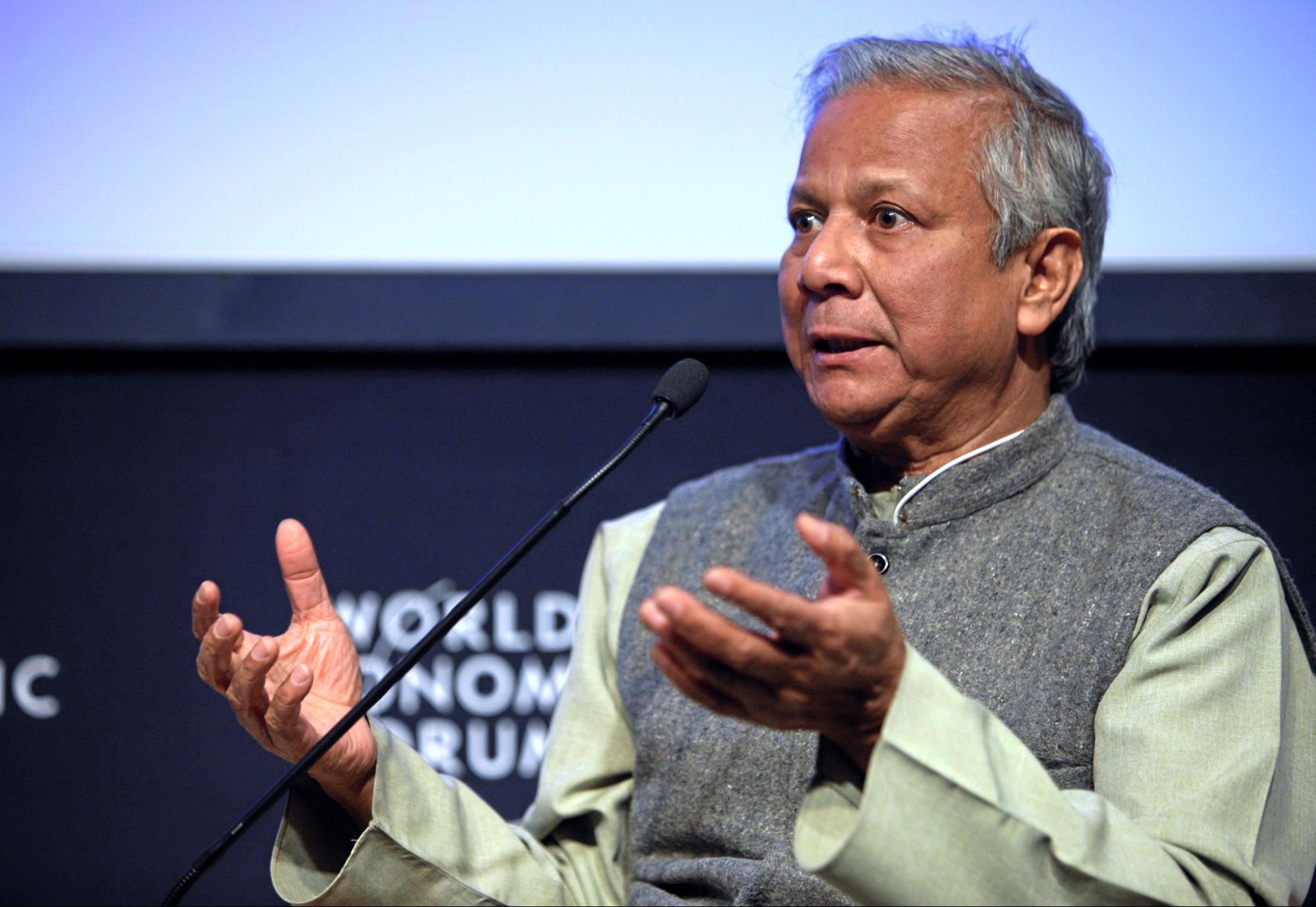

A grassroots version of the microloan strategy was popularized by the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh (founder Muhammad Yunus in figure 5.15). Through this project, mini banks are set up in villages that provide loans to groups of five people at a time. No collateral is required to receive a loan, and no written contracts are required between the bank and the borrowers; instead, the system works based on trust.

While the Grameen Bank began in the 1970s, it grew significantly between 2003 and 2007. It has loaned $2.1 billion to approximately 2 million people, 94 percent of whom have been women (Hazeltine and Bull 2003). Watch the 3:26-minute video “The Grameen Model: Technology + People” [Streaming Video] (figure 5.16) to hear how the Grameen Bank works in more detail. What do you notice is different about the Grameen strategy from the more traditional development approaches we’ve covered in this chapter?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ir6Z724Tvdg

Another example of people-centered poverty reduction lies in organic farming. Organic agriculture is “a method of production that forgoes the use of pesticides and chemicals in favor of practices that respect the health and purity of the land on which production occurs” (Bloechl 2018). As we described earlier in this chapter, the use of chemicals and pesticides can cause long-term damage to land that could otherwise produce valuable resources. When farmers are supported in returning to organic methods to fertilize and protect their crops, they can benefit in several ways.

With organic methods, farmers can earn higher incomes than with conventional farming, as there are lower costs of production and maintenance. Food insecurity is reduced, as organic farming allows farmers to grow a diversity of crops, relying on surviving crops if others fail in a given season. Farmers are able to have subsistence farms, living off their own production. And organic farming prevents a myriad of health issues that often arise with the use of pesticides and chemicals (Bloechl 2018).

Watch the 6-minute video “After the Green Revolution” [Streaming Video] (figure 5.17). It tells the story of the crisis in India but adds how the Green Revolution instilled a reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, sending farmers into a spiral of debt, poisoning the soil, and leading to decreasing yields (The Sustainability Institute 2015). As you watch, pay attention to how the main narrator, Dr. Kate, encourages academic scientists to work with village farmer-scientists to solve agricultural problems. How is the role of academic scientists portrayed in comparison to the farmers?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWptheft724

500 Years of Resistance to Colonization and Globalization

In many corners of the world, we can see resistance to the priorities of foreign assistance, humanitarian aid, and development that are harmful. Take, for example, the Zapatista uprising that began in 1994 in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Prior to the uprising, Mexico had undergone a decade and a half of austerity reforms under the direction of the IMF. The IMF required Mexico to eliminate food subsidies for basic foods like beans, tortillas, bread, and rehydrated milk (McMichael 2017).

Minimum wage was cut in half while the cost of basic necessities increased. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—a neoliberal trade deal between Canada, the United States, and Mexico—threatened to exacerbate these trends. And so it was on the day that NAFTA came into effect, January 1, 1994, that Indigenous people from Mexico’s poorest state, Chiapas, took up arms.

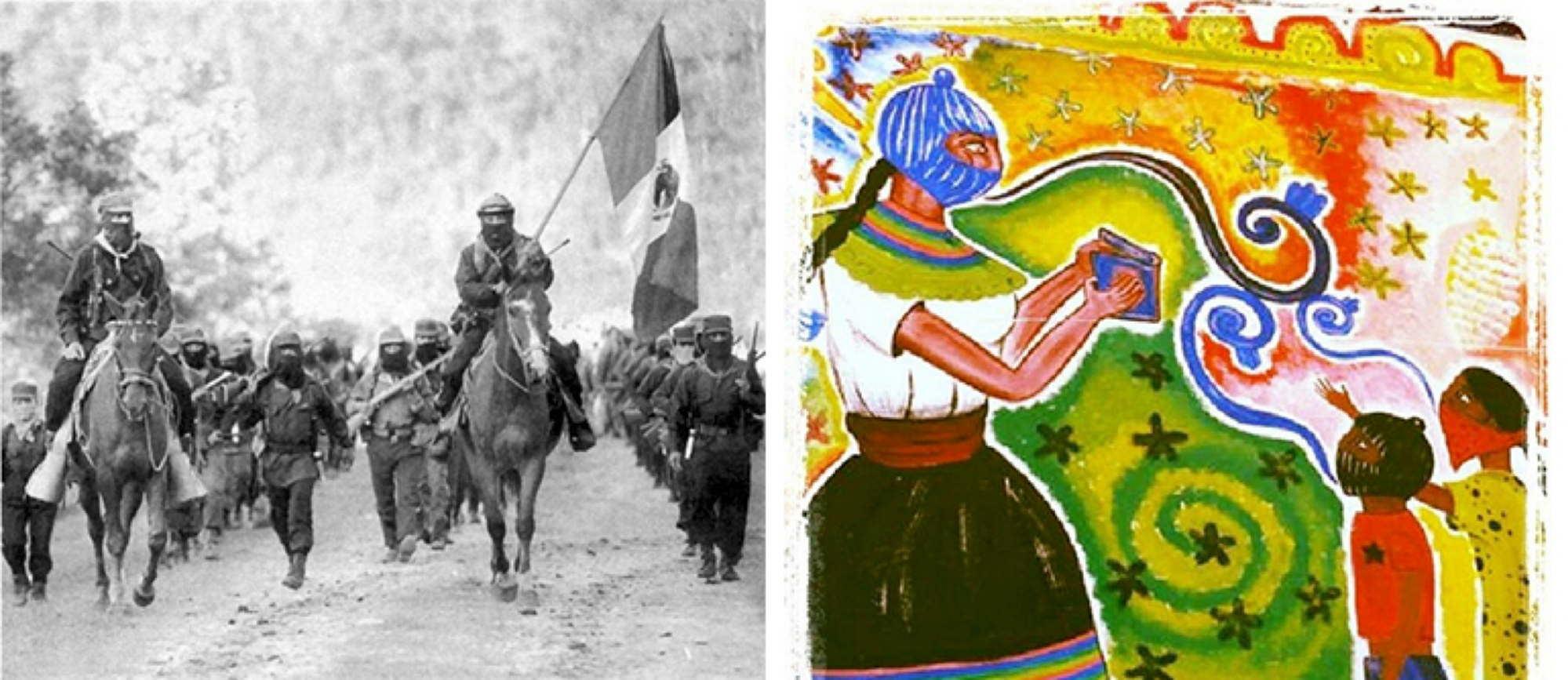

The Zapatistas would go on to transform resistance movements around the world for their generation (Holloway and Peláez 1998). They sought autonomy to build their own communities on their own radically democratic terms, but unlike most revolutionary movements in history, they didn’t seek state power or government office. As their spokesman Subcomandante Marco once said, “They do not understand that we are struggling not for the stairs to be swept clean from the top to the bottom, but for there to be no stairs, for there to be no kingdom at all” (Holloway and Peláez 1998:4).

The Zapatistas also didn’t seek recruits. Instead, they tried to forge a non-hierarchical network of communities in resistance to neoliberal globalization. As they put it, they were fighting against the one No and for the many Yeses. “We want a world in which there are many worlds, a world in which our world, and the worlds of others, will fit: a world in which we are heard, but as one of many voices” (Holloway and Peláez 1998:4) (figure 5.18).

The Zapatistas were partly responsible for inspiring the activists who organized the massive mobilization against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle, Washington, in 1999. There, a broad coalition of groups, from environmentalists to steelworkers, staged street demonstrations of 100,000 people with the goal of disrupting WTO trade negotiations. They succeeded, both preventing a new WTO agreement and pushing the arcane world of international trade policy into the realm of public debate. Over the past two decades, the “Battle in Seattle” has found its way into Pacific Northwest lore.

Twelve years later, in 2006, 70,000 teachers walked out on strike in Oaxaca, Mexico (figure 5.19), a neighboring state to Chiapas. They demanded better resources, wages, and working conditions. Teachers created a protest camp, erecting tents and community spaces within the Zócalo, the city’s central plaza, a tactic that would later be used in Cairo, Egypt, during the Arab Spring and Portland, Oregon, during Occupy Wall Street.

On June 14, 2006, in the middle of the night, police violently raided the teachers’ camp, beating and arresting strikers and burning their tents and supplies. The next morning, the city erupted. Tens of thousands of people from various walks of life marched back into the Zócalo, pushed the police out, and held the camp for the remainder of the summer. Massive protests transformed the city, and community members formed a kind of alternative congress called the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca, which was organized according to an Indigenous democratic practice known as usos y costumbres (literally translated as “customs and traditions”).

Both the Chiapas and Oaxaca protests occurred during eras of neoliberal austerity. But the roots of protesters’ concerns have a historical basis. They are part of a centuries-long process of resistance to colonialism and globalization. While resistance has been ever-present, it has varied widely in terms of tactics used and goals pursued.

Today, resistance to colonialism and globalization continues to take many forms, from the Standing Rock fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline to the Sunrise Movement’s youth mobilizations against the perpetrators of the climate crisis. Perhaps we could think of it as a kind of “movement of movements.” Each of these movements has its own history, identity, and goals, but they also exist within a network of other movements, with at least some shared values and some common antagonists. One common thread runs through many resistance movements: people haven’t just been fighting against imposed forms of power and exploitation, they have also been fighting for innumerable alternative ways of life.

In all their diversity, these movements not only seek to challenge the injustices of the dominant paradigm established for international relations. They also uplift alternative ways of knowing, relating, and living in community. In doing so, they remind us that the social world is made, and that it could be made differently. As the slogan of the World Social Forum puts it, “Another world is possible.”

Going Deeper

- For more information on the Grameen Bank, watch this 9:44-minute video, “Pennies a Day” [Streaming Video].

- Watch this 2:44-minute video, “Vivir Bien” [Streaming Video] to make connections between Indigenous values, development, and Buen Vivir.

Licenses and Attributions for New Perspectives and Movements for Global Change

Open Content, Original

“New Perspectives and Movements for Global Change” except for “500 Years of Resistance to Colonization and Globalization” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“500 Years of Resistance to Colonization and Globalization” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.14. People’s Health Clinic in Portland, Oregon is posted from the Operation Nightwatch Portland Facebook page and included under fair use (left). Poster for Community Care Night is posted from the Sisters of the Road Facebook page and is included under fair use (right).

Figure 5.15. “Muhammad Yunus” is on Flickr by World Economic Forum and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 5.18. “Members of the Zapatista army” is on Flickr by Javier Martin Espartosa

and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (left). Twenty years of Resistance. Zapatista Uprising. 1994-2014 by @tatismami97 is on Flickr by Pedro and licensed under CC BY 2.0 (right).

Figure 5.19. “Teacher’s Strike in Oaxaca, Mexico 2006” by R4che1 is on Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.16. “The Grameen Model: Technology + People” by Grameen Foundation is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.17. “After the Green Revolution” by The Sustainability Institute is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

an initiative to increase the global food supply and reduce world hunger by the use of chemicals and engineered crop varieties.

the communities, groups, and organizations that function outside of government to provide support and advocacy for certain people or issues in society.

aid given by a national government to countries in need.

aid to alleviate suffering and mitigate the effects of disaster provided by governments and non-governmental organizations for a short-term period until longer-term help can be provided by local governments or other institutions.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

a statistical estimate based on averages, of the number of years a person can expect to live in a certain region.

the government agencies, non-governmental organizations, philanthropic private businesses, individuals, and their actions, working to address poverty and inequality at a global scale.

the laws and practices that requires disabled students be included in mainstream classes - not separate rooms or schools.

a process of decentralization—shifting economic activity into the hands of millions of small and medium-sized businesses instead of concentrating it in mega-corporations.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure.

mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to completely change every aspect of society.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.

a form of collective action when workers in a given workplace refuse to work until owners meet their demands.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

a set of ethics that balance quality of life, democracy, giving inherent value to all living things, and collective well-being.