6.5 U.S. Economic Change Over Time

Whatever the root causes of the rise of capitalism, it is clear that the capitalist economy has shaped the lives of the people who live within it. And as capitalism took on different forms within different time periods, lives changed. While economic inequality has been increasing in the United States for decades, it wasn’t always like this.

From 1945 to 1975, income inequality decreased in the United States (Noah 2013). In other words, the gap between the rich and the poor was shrinking. This can be explained partly by the booming economy after World War II, but more importantly also by the rise of a strong labor movement. The labor movement increased wages, benefits, and working conditions for most U.S. workers, even those who weren’t unionized.

Declining inequality was also enabled by the New Deal, a series of government initiatives installed between 1933 and 1938 during the Great Depression. The New Deal rapidly increased the number of well-paid government employees and put people to work building roads, bridges and other public works. It also created a social safety net via Social Security to unemployment insurance and subsidized housing. Finally, after the catastrophe of the Great Depression, the government began to increase regulations on corporations and banks designed to protect the public interest (Noah 2013).

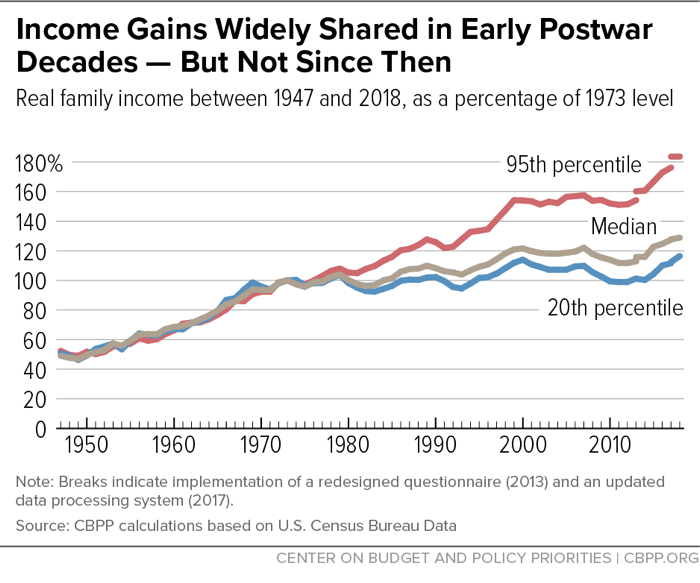

Inequality began to increase dramatically in the mid-1970s following a series of policy changes that began to reverse the New Deal (Noah 2013) (figure 6.7). Many conflict theorists argue that the economic and political changes that began in the early 1980s were orchestrated by the rich (specifically, corporation owners) against the working classes. Following the election of Ronald Reagan in 1981, the federal government began adopting neoliberal economic policies.

As discussed in Chapter 5, neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that emphasizes free trade, benefits of globalization, and a minimal government role in the economy, including spending. Confusingly, given its name, neoliberalism has been primarily advocated by the conservative and libertarian movements. However, it became so widespread that many liberal leaders (like Bill Clinton) also adopted it.

Neoliberalism calls for cutting back social services, loosening regulations on corporations and banks, lowering taxes (especially the taxes on the rich), and opening international trade. Known as “trickle-down” economics, these policies were passed in the name of boosting economic growth by creating a more business-friendly environment.

The decreased taxation of businesses resulted in fewer dollars to fund government programs for the lower classes. At the same time, business was able to undermine the already faltering labor movement. The major industries in the U.S. economy, which tended to be strongly unionized, were increasingly automated, and their production was moved offshore as business owners sought cheaper labor and looser regulations in the Global South.

In a short period of time, the U.S. economy transformed from a production economy to a service economy. Many working-class jobs in the 1960s (at lumber mills, meatpacking plants, auto factories, and the like) were unionized and usually offered relatively high wages and benefits. One worker could support a family and perhaps buy a modest home. Today, most working-class jobs are in the service sector (retail, food service, call centers, and so on). They pay minimum wage or slightly better, and offer minimal benefits. They tend to be part-time and temporary, with limited opportunities for promotion.

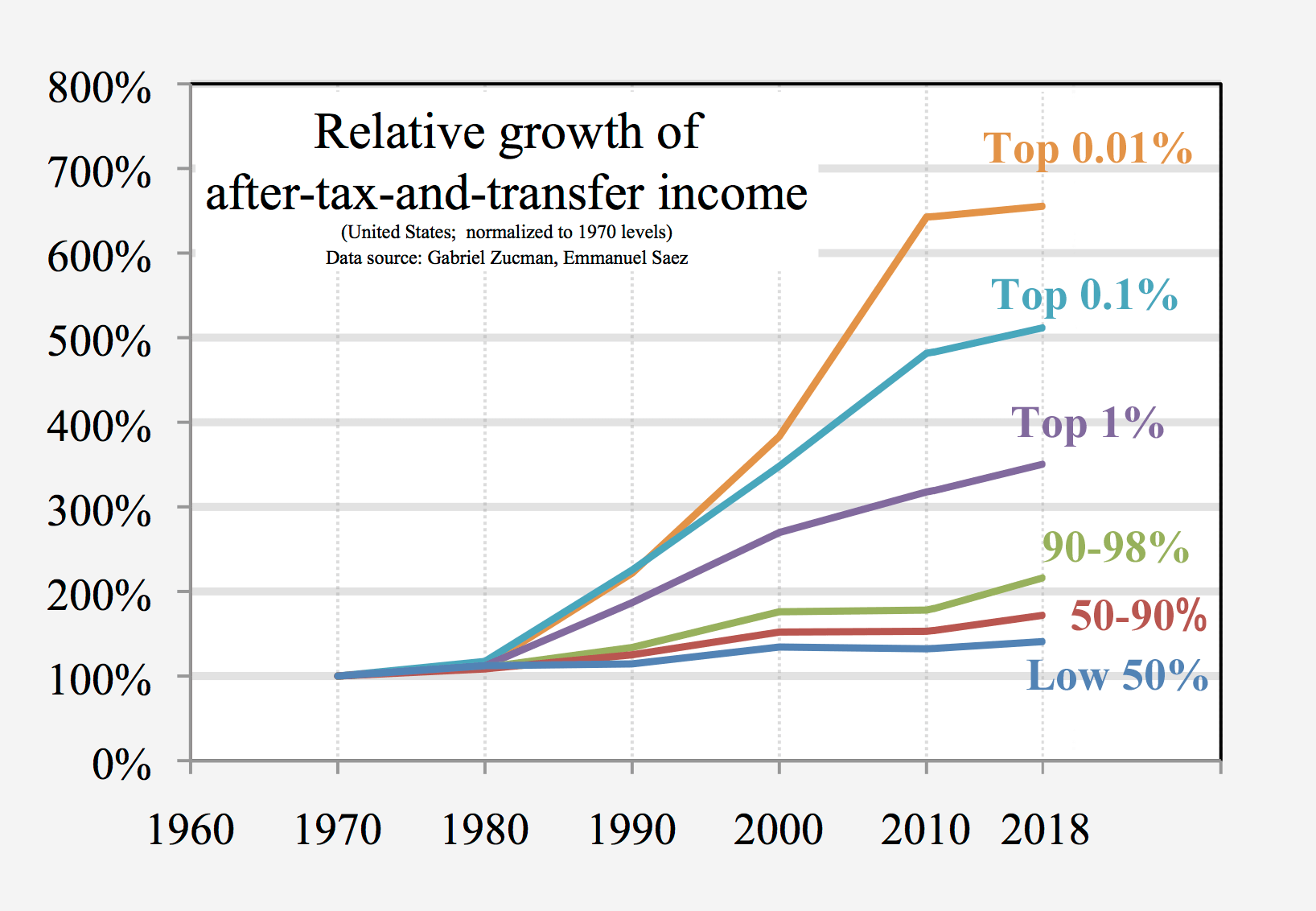

The effects of these economic changes have been striking. The rich have done marvelously well in the last few decades. They’ve seen their wealth and power increase markedly. However, the poor, working class, and middle class have seen their wealth and income shrink or stagnate (Noah 2013). In the graph in figure 6.8, notice that between 1970 and 2018, in the United States, most income growth had gone to the wealthiest members of society: the 1 percent, 0.1 percent, and 0.01 percent. We introduced the wealthiest 1 percent at the global scale in Chapter 4. The pattern is similar at the national level.

As we’ve seen, economic systems change over time. But what causes that change? There are certainly many answers to this question. We’ll explore two: technological change and class conflict.

Technology

The development of new technologies can transform an economy, altering not only the methods of production but also the human relationships and dynamics of power. Famously, industrial production was transformed in the early 20th century with the development of the assembly line.

First implemented in Ford’s car assembly plants, the assembly line increased economic efficiency by breaking the production process down to a series of small actions performed repetitively by workers. A single worker might spend 10 hours performing the same task as one car after another moves down the line in front of them, as shown in figure 6.9.

This new production system produced more vehicles per “man-hour,” meaning that a given number of workers could produce more cars in a single day. It also made labor increasingly monotonous (and often dangerous) for workers. So this new technology of production, the assembly line, created new efficiencies as well as new forms of labor and relations of power. And since these efficiencies increased the profits, business leaders implemented the assembly line in all kinds of industries, from fast food to fast fashion.

More recently, the development of massive data collection has enabled new economic opportunities and relationships of power. Harvard Professor Shoshana Zuboff argues in her book Surveillance Capitalism that the rise of big data marks a shift in the economy akin to the development of the assembly line. Entirely new markets have emerged that use surveillance data collected by various apps and websites to predict consumer behavior. For example, social media algorithms on sites like Facebook determine which ads they will show you. Zuboff warns that “surveillance capitalism” threatens to undermine our ability to function as a democratic society.

Technological changes in the economy often come “from above.” In other words, economic elites develop and implement new technologies to serve their interests. However, there are also significant ways in which economies can be changed “from below.”

Organized Labor

Throughout the history of capitalism, the lower classes have consistently resisted economic arrangements they see as exploitative. Over the past century in the United States, workers have successfully redefined the economy in profound ways, from fighting for the 8-hour day and 40-hour week to pushing for worker-oriented legislation, like rules that support worker safety, minimum wage laws, and Social Security.

Today, many workers are fighting to retain these past gains and pushing for things like increased wages, predictable schedules, and healthcare benefits. Watch the 9-minute video, “The Fight to Make Bad Jobs Better” [Streaming Video], about the work experiences of many retail and food service workers (figure 6.10). As you watch, ask yourself: How do “flexible schedules” impact different groups differently: workers, owners, and consumers?

The Fight to Make Bad Jobs Better

How do workers, who appear to have little power within a workplace, successfully push for higher wages, benefits, and improved working conditions? Probably the clearest answer is through organizing collectively within a union.

A union is an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions. Workers and business owners typically have competing interests. Business owners have an interest in maintaining a low cost of production in order to maximize profits. That means that for the business owner, it is usually ideal to keep wages as low as possible and working conditions under their discretion.

However, workers usually have an interest in increasing their wages and establishing working conditions that maintain their safety at work and quality of life outside of work. In the current service industry, for example, workers often want higher wages and stable schedules, while owners often want lower wages and “flexible” schedules. So, as conflict theorists in sociology have often pointed out, there is a structural conflict between the interests of workers and owners within capitalism.

If the interests of workers and owners are structurally opposed, how do workers achieve their goals against the interests of their bosses? Since owners rely on the labor of workers, workers can pressure owners by threatening to collectively refuse to work. This is called a strike. A strike is a form of collective action when workers in a given workplace refuse to work until owners meet their demands (figure 6.11).

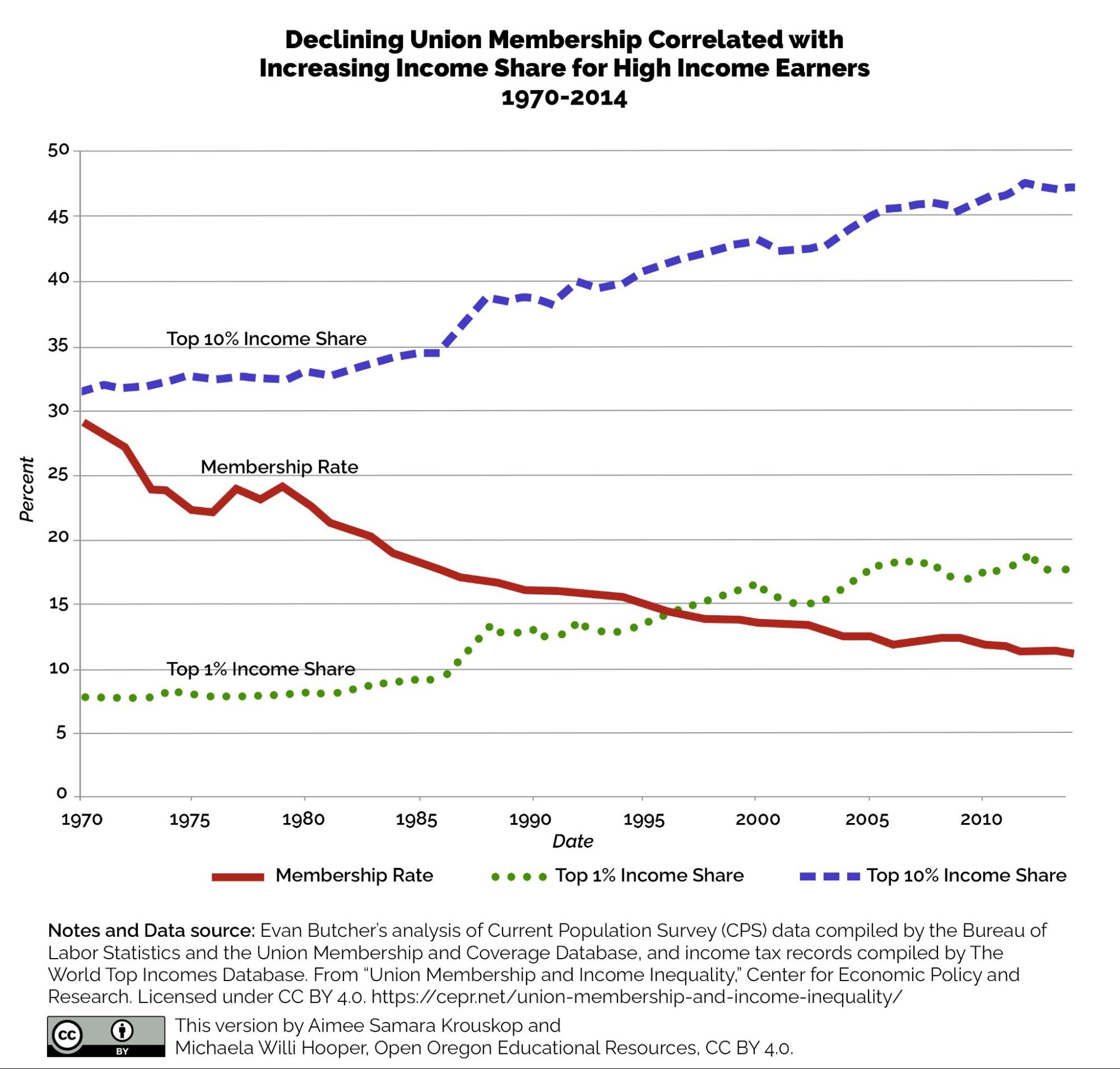

Over the past century, the relative power of the labor movement has significantly impacted workers’ wages and working conditions. Workers in unions usually earn higher wages than non-unionized workers. But a high level of union membership can even lead to higher wages for non-unionized workers, since they lift the overall wages of the labor market.

Partly for these reasons, periods of high union membership (like the 1940s to the 1970s) are associated with higher wages for most workers, while periods of lower union membership (like the late 1970s to the present) have seen declines in wages for most workers, when adjusted for inflation. As seen in Figure 6.12, union membership has been declining since 1970, while the income shares of the top 1 percent and top 10 percent have increased.

Currently, workers around the United States have been increasingly organizing, winning union representation at companies like Starbucks and Amazon. Whether the labor movement will reverse the trend of declining real wages remains to be seen.

May Day: A Labor Movement Case Study

The year 1886 is arguably the most revolutionary in U.S. history (Brecher 1997). U.S. workers were facing a new form of labor—industrial wage labor—and many of them saw it as un-American. Many even referred to it as wage slavery. Work days were long and dangerous, and low wages left most workers in poverty.

Some of the more radical organizers within the labor movement called for a general strike on May 1, 1886, to demand the eight-hour workday. A general strike is a strike of all workers within a society, not just the workers at one workplace or in one industry. It is perhaps the most powerful tool available to the working class (Brecher 1997).

When May 1, 1886, arrived, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike across the country. The movement for the eight-hour day was especially concentrated in Chicago, where tens of thousands of strikers marched through the streets, calling on their fellow workers to set down their tools, walk off the job, and join the strike. The city’s ruling class prepared for the strike by deputizing and arming thousands of men to put down the strike effort.

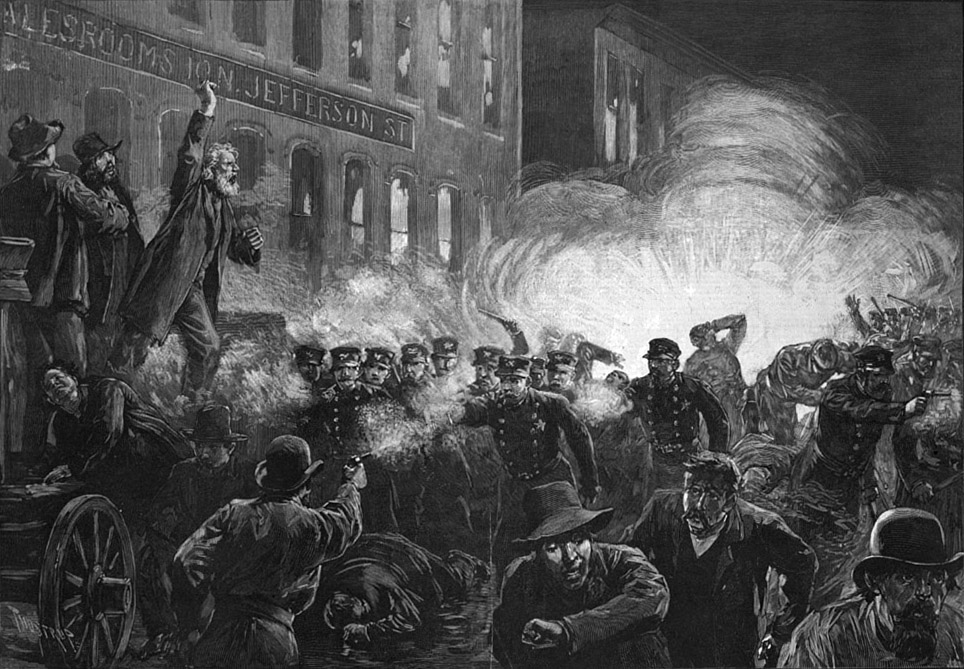

On May 4, anarchist organizers held a rally in Haymarket Square to protest the violent death of workers the previous day. The details of the events that followed are disputed by historians, but it is clear that after police began to push workers out of the square, someone threw a bomb toward the police, which exploded, resulting in the deaths of seven police officers (figure 6.13). After the bombing, the police then began shooting into the crowd of workers, killing at least four people.

Anarchism—a popular current within the labor movement at that time—is a political philosophy advocating for the elimination of all or most forms of hierarchy, including the abolition of the state. Many anarchists are committed to a basic set of principles, including mutual aid (the sharing of resources), the use of political protest to achieve a goal, and horizontalism (a non-hierarchical organizational system in which decisions are made by consensus).

It is important to note that anarchism is not inherently related to violent protest. Like with all political philosophies, its followers vary in thinking and action. They include those who support violence in the face of unjust acts as well as those who reject all forms of violence. Many also fall in between (Anisin 2019). However, the events at Haymarket Square—and the media reaction to it—resulted in a new stereotype of the bomb-throwing anarchist.

The Haymarket Massacre, as it has come to be known, provided a pretext for authorities to criminalize the labor movement across the country. At least 50 union halls and worker hangouts were raided nationwide. In Chicago, eight prominent anarchist organizers were arrested on false charges of planning the bombing. Despite no evidence linking them to the bombing, four were hanged and one was violently killed while behind bars. The survivors were later pardoned by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, who stated that “the judge [who ordered the hangings] conducted the trial with malicious ferocity” (Brecher 1997).

The eight-hour day campaign is commemorated around the world as “May Day,” or International Workers’ Day (Linebaugh 2016). However, most U.S. workers don’t remember it. Why is that?

In 1894, President Grover Cleveland and conservative union leaders declared a federal “Labor Day” in September, effectively distancing the labor movement from the more radical tradition of May Day. In 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower declared May 1st “Law Day.” Over the years, May Day was largely forgotten by most U.S. workers. In the past two decades, however, May Day has begun to re-enter mainstream political consciousness in the United States. This is the result of workers from outside the United States, who have a tradition of celebrating May Day, migrating to the United States and bringing that tradition back home, so to speak.

For example, on May 1, 2006, immigrant workers in the United States organized a general strike, dubbed “A Day Without Immigrants” (figure 6.14). Over a million people participated in immigrant rights protests across the country. In doing so, they reminded the broader U.S. working class of a piece of its own history.

Memory matters. When workers lose the memory of past movements, such as the May 1st general strike, what else do they lose?

The U.S. Labor Movement Today

Since 2019, workers in the United States have achieved several victories. Labor improvements have been gained for Hollywood actors and writers, nurses, emergency room techs, airline pilots, autoworkers, and delivery drivers. Many industries saw successful union organizing for the first time. In 2022, workers at an Amazon warehouse in New York City voted to become the first to create a union at the company.

Achieving a union at Amazon was significant because it is the second-largest employer in the United States, and organizers were faced with considerable obstacles. Watch the 5:36-minute video, “Inside Amazon Labor Union: How Workers Took on Amazon and WON” [Streaming Video] that explores workers’ organizing efforts at Amazon (figure 6.15). What challenges have they faced? How did they attempt to overcome them?

Workers at Starbucks have also achieved major historic gains in their organizing efforts. They successfully organized a union (Starbucks Workers United, or SWU) in Buffalo, New York, in 2021. This was something many saw as nearly impossible, but the workers did so, despite aggressive and illegal union-busting actions from Starbucks. Those actions included monitoring, disciplining, and firing employees engaged in organizing; promising new benefits to workers and adding workers to stores to discourage union support; refusing to bargain; and engaging law enforcement to discourage the gathering of workers (Sanders 2023; Scheiber 2023).

Alicia Flores is a former employee of a Starbucks in Portland, Oregon, who played a leadership role in organizing a union at her store. She was fired in June 2023 after working for Starbucks for seven years, following similar circumstances to those experienced by workers in Buffalo. Watch the 6-minute video, “Alicia Flores and Starbucks Workers United” [Streaming Video] to hear how and why she began organizing within her workplace (figure 6.16). As you watch, consider the issues Starbucks workers face. Have you experienced similar issues in your own work life? Why do you think Starbucks management responded to Flores’ organizing in the ways they did?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fR2u0mh1_8M

Since Flores told her story in this video, Starbucks has been accused of illegally closing 23 stores nationwide to discourage union activities. The complaint came from the National Labor Relations Board, which is demanding that the company reopen all locations and pay for lost wages (“Starbucks Ordered to Reverse Closures After Shutting Down 23 Stores for Alleged Union Busting” 2023).

How is Flores’s experience connected to the broader structure of the economy, particularly the dynamics of the food industry? Does the response of her managers support or refute the theory that class conflict is built into the structure of the workplace?

Flores suggests that all workers would benefit from organizing in their workplaces. Many union leaders, like Flores, are first-time organizers, but they find themselves moved to change the unfair working conditions that their coworkers and they experience. For direction, they rely on projects such as the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee [Website], which is dedicated to creating a “distributed grassroots organizing program to support workers organizing at the workplace.”

Going Deeper

For more information on surveillance capitalism, watch this revealing interview with Shoshana Zuboff, “High Tech Is Watching You” [Website], conducted by John Laidler (2019) (about a 10-minute read). Consider these questions:

- How do surveillance and data enable new profits?

- How do surveillance and data create new forms of power?

For more on Starbucks union organizing, watch the 8:20-minute video “Why Starbucks Workers Fought to Unionize” [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for U.S. Economic Change Over Time

Open Content, Original

“U.S. Economic Change Over Time” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Image 6.11 and content on anarchism added by Aimee Samara Krouskop.

Figure 6.16. Alicia Flores and Starbucks Workers United by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 6.8. “Relative Income Growth by Percentiles” is on Wikimedia Commons, by RCraig09 and licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 6.9. “Ford Assembly Line” is on Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain.

Figure 6.13. “The Haymarket Riot” by Harper’s Weekly, on Wikipedia, is in the public domain.

Figure 6.14. “A Day Without Immigrants March” by Jonathan McIntosh, on Wikipedia, is licensed under CC BY 2.5.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.7. “Income Gains Widely Shared in Early Postwar Decades—But Not Since Then” by

Center on Budgets and Policy Priorities is included under fair use.

Figure 6.10. “The Fight to Make Bad Jobs Better” by Vox is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 6.11. “(35325) Local 174 Mural, “Untitled” 1937” © Elizabeth Clemens, Walter P. Reuther Library is included with permission.

Figure 6.12. “Declining Union Membership Correlated with Increasing Income Share for High Income Earners, 1970–2014” is adapted from “Union Membership and Income Inequality” by Evan Butcher, CEPR, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from Current Population Statistics, BLS, Union Membership and Coverage Database, and The World Top Income Database. Modifications: Redesigned for accessibility by Aimee Samara Krouskop and Michaela Willi Hooper.

Figure 6.15. “Inside Amazon Labor Union: How Workers Took on Amazon and WON” by More Perfect Union is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

a series of government initiatives under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, during the Great Depression. They focused on strengthening the economy by employing workers for public works and creating a social safety net with programs such as social security.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.

a political and economic ideology that emphasizes free trade, benefits of globalization, and a minimal government role in the economy, including spending.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the people at the top of the income and wealth distributions in the world

the structural antagonisms built into economic relationships.

a way for employers to increase economic efficiency by breaking the production process down to a series of small actions performed repetitively by workers.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

a form of collective action when workers in a given workplace refuse to work until owners meet their demands.

a strike of all workers within a society, not just the workers at one workplace or in one industry.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

a philosophical and political tradition advocating the abolition of all or most forms of hierarchy, including the state.