1.3 The Art of Sociology

Sociology is a science guided by the understanding that “the social matters: our lives are affected not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension” (The Health of Sociology 2007).

Sociologists study the culture of societies as we did in the Chapter Story. They explore how social groups shape our identities and behaviors. They also study how society is organized. They focus on the structures of society, such as how institutions—large-scale social arrangements that are stable and predictable, are created and maintained to serve the needs of society. We’ll introduce more of the structure of society in Chapter 2.

Lived Experiences of Social Change

In the previous section, we laughed along with the revelers in Lumière’s “Snowball Fight [Streaming Video],” and you may have been inspired to learn about the social realities that were present during its filming. With some research and some sociology, the setting and story expand, allowing us to ask more questions.

Late 1800s France was the center of the Belle Époque, or “Beautiful Era,” of Europe. It was a time of optimism; regional peace; economic prosperity; and technological, scientific, and cultural innovations. The life expectancy of children rose. Mass transit was new, and education was more available to many people. Literature, music, theater, and the visual arts flourished, especially in Paris. Daily news publications and advertising were expanding immensely. Running water, gas, electricity, and sanitary plumbing were more available to the middle class.

Disposable incomes were plentiful enough to enjoy luxurious items such as fashionable clothing and travel. The quality and quantity of food had improved, with the purchase of spirits increasing by 300 percent and sugar and coffee by 400 percent. Historians think of this era as full of hedonism, sexual liberation, and the fading of social barriers.

At the same time, tension and trouble existed in France, as in all places exploding with change. The French feminist newspaper La Fronde (The Slingshot) was first published in Paris in 1897, the same year that “Snowball Fight” was filmed. The struggles of female workers in match factories inspired Fronde’s founder, who was disheartened by how they were portrayed in the mainstream or “masculine” press. La Fronde publications covered issues of working conditions and equal pay for women. Its articles presented women as knowledgeable and opinionated on topics traditionally only assigned to men (Faiers 2021; Roberts 2002).

Politics became more divided, with the extremes of the left and right gaining support. Some groups viewed cultural changes afoot as decadent and immoral. While some members of the lower classes experienced improved living conditions, most urban poor still lived in cramped homes, received low wages, and faced terrible working conditions and poor health. The government still delivered capital punishment publicly with the guillotine. Society, including politicians, challenged the status of the Catholic Church at this time, and anti-Catholic laws were passed restricting religious instruction in all schools. There was a push to require civil (rather than church) marriages. Divorce emerged in the mainstream consciousness as an option for unhappy unions.

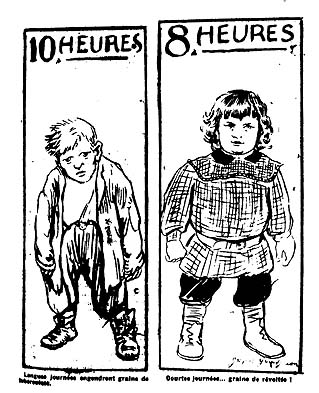

Tuberculosis was a dreaded disease, causing 100,000 deaths annually (Mitchell 1988) and changing society in many ways. Citizens battled over laws regarding health services, the registration of people who had the disease, and the mandate of quarantines. Tuberculosis was still a concern in the early 1900s, when the newspaper, La Voix du Peuple (The Voice of the People) published the two cartoons in figure 1.6. One image shows a sickly worker underneath the words “10 hours” with the caption: “Long days breed the seed of tuberculosis.” The other image shows a much healthier individual underneath the words, “8 hours.” This image clearly identified the dual sentiment of fear of tuberculosis and the campaign for workers’s rights at the time (Barnes 1995).

How might these social circumstances have shaped the lives of the rowdy crew of Lyons? For example, considering the progressive representations of women in the media, was it liberating for them to ice-brawl with men in the street? Cinematography had just been made possible. How might this brand-new recording format have shaped their experience that day? Most medical professionals at the time agreed that one was vulnerable to tuberculosis if deprived of air, sunlight, and exercise (Mitchell 1988). Was fear of tuberculosis a partial driver of their participation? How might other social circumstances have shaped the experiences of these snowball fighters?

We can also see patterns between the Belle Époque in France and other social realities across time and place. For example, the United States is currently experiencing political polarization as well. In 2022, U.S. employees of Starbucks organized the company’s first unions, demonstrating that workers’ struggles are an ongoing social issue. We are reminded that U.S. and European societies have often struggled with how to deal with pandemics, as we have struggled with COVID-19. It may be universal that during each pandemic, some groups rebuke the mandates of social leaders (such as masks and quarantine) designed to curb the spread of disease.

These social realities of the late 1800s in France are snapshots of how society shifted in the country, Europe, and the world. These are examples of social change, or the transformations in human interactions and relationships that happen over time and transform cultural and social institutions. In this way, sociology also asks:

- How do societies change and why?

- In what ways do human interactions, behavior patterns, and cultural norms change over time?

Imagine yourself as an adult in France in 1897. How would the social attitudes, circumstances, and social changes have influenced your life at the time? How would they have influenced your life if you were a working-class Catholic man? An upper-class teenager? How would your family have been affected? How would the diverse communities of Lyons be influenced?

The Study of Social Change with an Equity Lens

Sociology also goes further to examine connections that may not be as easy to see, particularly not as easy to see by the white, upper-middle-class professionals who still make up the majority of sociologists today. A good sociological study of social change is done with an equity lens. An equity lens acknowledges that race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality are related to social inequality, the unequal distribution of power, resources, rewards, and positions in societies. Some examples of social inequality include a lack of representation of people of color in government, unequal access to safe homes, uneven access to quality health care, and income gaps between women and men.

Sociology done with an equity lens pays attention to how changing human interactions, behavior patterns, and cultural norms affect groups who live with less access to opportunities and services, experience discrimination, or are the targets of violence and oppression. Further, this lens informs action to identify and address systems of power, privilege, and oppression.

For example, the study of social change with an equity lens devotes attention to the impact of social change among Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). It inquires about the impact of social change among people who identify outside of the gender binary (the notion that gender is exclusive to being a man or woman). It examines how people living with disability, veterans, new immigrants, or those who practice a religion prone to discrimination experience social change. Social change can create improved circumstances for members of those groups, or it can exacerbate inequity and violations of civil and human rights.

At the same time, studying social change with an equity lens means being vigilant about identifying the (often hidden) role that members who identify within these groups play in influencing social change. Let’s see how we might expand our study of the Belle Époque with an equity lens.

Eurocentrism and the Belle Époque

We often read about the Belle Époque described through a Western and white lens. For example, an internet search of art from the Belle Époque reveals the gaiety, artistry, and playfulness of this time. One good example is the painting in figure 1.7 by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance.

However, it is not as easy to find images of people of color from this era in France. That’s because the work of white French artists has been elevated in museums and used to depict this time period. There is a noticeable absence of artistic representation by people of color in our accounts. This is one of many examples of Eurocentrism—a worldview, mindset, or communication that centers white European ways of knowing as sole, central, or superior to all others.

Painter Kehinde Wiley makes a statement about this Eurocentrism in his series A New Republic. He portrays contemporary African Americans using the conventions of traditional European portraiture, drawing attention to the absence of African Americans from historical and cultural narratives (figure 1.8).

We have to study deeper to learn how immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean, and North America lived in European cities at the time. For example, we know that many Black U.S. immigrants had come to France following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, when the United States acquired a large piece of land from the French. Suddenly, Black people went from living free in a French territory to living in a state with a policy of segregation and political, social, and economic discrimination against non-whites. Instead of enduring life under those circumstances, an estimated 50,000 free Black people chose to emigrate to France (Beardsley 2013).

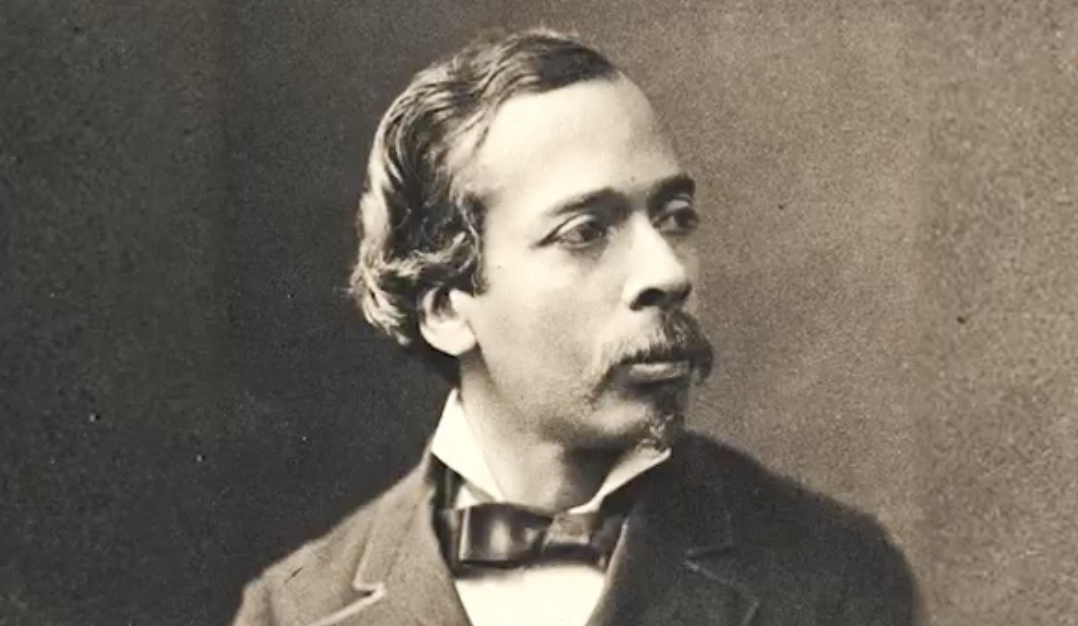

By the Belle Époque, Black people were working in domestic service or as laborers, seamen, musicians, dancers, and other entertainers (Childs and Libby 2017). There were also high-profile Black individuals of this era in France. While their presence is limited, some have been acknowledged in print. For example, Severiano de Heredia, a Cuban-born biracial politician, served in what was the equivalent of the mayoral post in Paris from 1879 to 1880 (figure 1.9). He was the first mayor of African descent of a Western world capital (Audureau 2020; Triay 2015a).

Heredia’s contributions to the progressiveness of the Belle Époque included initiatives to support universal and continuing education, libraries, and the environment. He favored the separation of church and state, a free press, women’s rights, and child labor reforms. He is noted for his response to a severe winter during his term, finding shelter for the unhoused and employment for 12,000 Parisians (Mayeur and Arlette 2001). Heredia also dedicated his work to the building and improvement of electric cars (Atisu 2019). However, he did not receive public recognition for his work until 2013, when a walkway was named in his honor in Paris (Triay 2015b).

The Belle Époque as an Algerian

What else can we learn about the experiences of people of color during the Belle Époque? We know that colonialism played a major role. Colonialism is the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

France has been a colonizing state since the 1600s. But by the Belle Époque France had recently taken over territories in Vietnam, Cambodia, China, Tunisia, and Gabon, adding to its colonial expansion (Chafer 2002). Immigrants fled from these countries due to the violence and destruction of their ways of survival, which is part of the colonization process. So by 1897, and the filming of “Snowball Fight,” immigrant groups from these countries also existed in France (House n.d.).

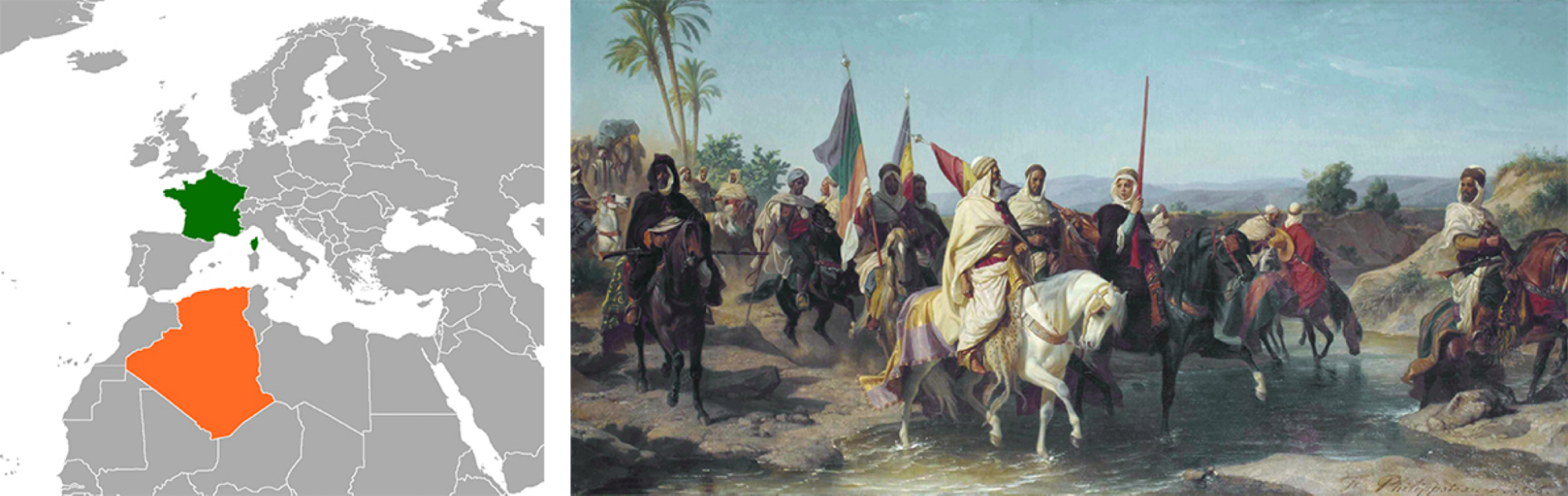

The French military invaded Algeria in 1830. Because Algeria had many more settlers than other colonies and was close geographically, the French government invested great effort in maintaining its power and resources there. After France conquered Algeria’s military, they spent 40 years squashing Tribal rebellions with campaigns and scorched-earth colonization operations, a tactic that destroys or steals all resources and assets (figure 1.10).

As a result, Algeria suffered land grabs, wealth extraction, massacres, deportations, famines, and epidemics for 40 more years. Eventually, 825,000 Indigenous Muslims were killed (Phipps 2021). This level of death and oppression is considered genocide, the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

The colonization and genocide of Algeria was supported by ideas spread by the Catholic Church that cast Algerians as racially inferior and socially undeveloped. Muslim practices such as women wearing veils and the separation of genders were touted as backwards and in need of intervention, particularly to “save” the Muslim women. The idea was that a morally and benevolent French rule could modernize and improve their lives. With this rationalization, tens of thousands of Algerians were sold as enslaved people or brought to France to work in mines (Phipps 2021).

Knowing these bits of history, it is possible to find images of Islamic Algerians under French rule. Many, taken later in the Belle Époque, are photographs that had been taken for postcards in occupied Algeria and sent back to France for sale. Frequently, women were depicted in a way that catered to the romanticized notions that French citizens held of Algerian habits and culture. As author and critical theorist Sarah Sentilles writes, “…they imagined them: lounging in harems, smoking hookahs, trapped in the prison of their own homes, topless, sexually available” (Sentilles 2017).

While this was far from reality, and most Algerian Muslim women wore veils in public, the photographers capitalized on the opportunity to provide images suited to these stereotypes. Sentilles writes:

They hired models, often from the margins of society, and paid them to pose and to wear costumes. In their studios, the photographers used props and backdrops to create bedroom interiors, decorated spaces with hookahs and coffee pots and rugs to look like harems, and placed bars on windows to produce a sense of imprisonment. If Algerian women would not take off their veils voluntarily, the photographers would pay them to do so (Sentilles 2017).

Figure 1.11 is a good example of hundreds of staged photographs taken of Algerian women under French occupation during the 19th century.

With this background, it’s easier to shape an informed idea of what living in Algeria would have been like after France invaded. It’s also easier to understand what living in France as an Algerian might have been like. Most likely, we would have emigrated by force or economic need. In all cases, our lives and the lives of our families and community would have been dramatically affected by the social changes that developed due to the occupation.

Tracing History’s Impact on the Present

Another task crucial to the art of sociology with an equity lens is understanding how social circumstances and social changes in the past influence social dynamics of the present. For example, in France today, full facial veils are banned in public spaces. Likewise, religious head coverings are illegal in schools and government buildings. Proponents say these laws are intended to dampen religious “extremism,” while critics say they unfairly target the country’s minority Muslim population.

In 2021, the French Senate voted to ban girls under 18 from wearing the hijab in public spaces. The vote also gave administrators of public swimming pools the right to ask women not to wear burkinis, the whole-body swimwear worn by some Muslim women. The amendment sparked a social media campaign, including the Instagram image in figure 1.12 posted by model Rawdah Mohamed. Her hashtag #HandsOffMyHijab trended widely.

In 2021, Catherine Phipps wrote an article that relates France’s colonial past to the country’s increased restrictions on Muslim women wearing veils. She refers to imperialism, the practice of a nation forcefully imposing its rule or authority over other nations, and makes these connections:

These efforts to “liberate” Muslim women reiterate attitudes about women’s bodies and religious symbols that are rooted in the history of French imperialism. They echo French justifications for imperialism abroad, which was framed as a “civilizing mission” that masked widespread colonial violence. Such attitudes are rooted in centuries of beliefs of racial superiority and a need to “protect” Muslim women. By recognizing this historical tie, we can see how the overt violence inherent in imperialism is still influencing the daily lives of many Muslim women in France today (Phipps 2021).

In many ways, the attitudes, power structures, and discrimination known during Colonial France continue today. Applying an equity lens, what other historical social circumstances and changes can you imagine may have influenced the lives of people in France during the “Snowball Fight” of 1897?

Going Deeper

- For more connections between French colonialism and current life in France, watch this 13:59-minute video: “France’s Colonial Past and Race Relations Today” [Streaming Video].

- To learn more about the staged images of women in Algeria, see Zara Choudhary’s article “Unveiling the Algérienne: French Colonial Photography” [Website].

- To read more on how the visual arts imagined Black Europeans during the 19th century, read about an exhibition titled “The Black Figure in the European Imaginary” in the article “The Black Figure in European Art” [Website].

- To hear more about Kehinde Wiley and his work, watch “Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic” [Streaming Video].

- For more on Rawdah Mohamed’s story, see her Instagram page.

- To learn about the resistance efforts of Algerians during the Algerian War (1954 – 1962), which led to Algeria’s independence, watch “The Battle of Algiers” [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for The Art of Sociology

Open Content, Original

“The Art of Sociology” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.6. “Cartoons printed on page 3 of La Voix du peuple” is in the public domain. Courtesy of David Barnes/University of California Press.

Figure 1.7. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, French – At the Moulin Rouge-The Dance,” on Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain. Courtesy of the Google Art Project.

Figure 1.8. Painting by Kehinde Wiley, in the series: “A New Republic” on Flickr by Garrett Ziegler is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (left).

Figure 1.9. Screenshot of Severiano de Heredia is from the video, “Memoria de la Habana 167 Severiano de Heredia” by Ramon Fernandez Larreacanal, and licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 1.10. “Map indicating locations of Algeria and France,” on Wikipedia, is in the public domain. “Chérif Boubaghla and Lalla Fatma n’Soumer, by Félix Philippoteaux,” Kiddle encyclopedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 1.11. “Unveiling the Algérienne: French Colonial Photography” is in the public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.8. Screenshot of Kehinde Wiley is from the video, “Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic” by the Brooklyn Museum and licensed under the Standard YouTube License (right).

Figure 1.12. “Hands off my Hijab” is found on Instagram and is included under fair use.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

a statistical estimate based on averages, of the number of years a person can expect to live in a certain region.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

recognition that we do not all receive the same power and resources in society. This informs action to identify and dismantle systems of power, privilege, and oppression.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

a worldview, mindset, or communication that centers white European ways of knowing as sole, central, or superior to all others.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

land acquisitions that are in violation of human rights, without prior consent of the preexisting land users, and with no consideration of the social and environmental impacts.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the practice of a nation forcefully imposing its rule or authority over other nations