10.11 Conclusion

Social movements reflect responses to a myriad of social problems. This chapter first provided a broad introduction to social movements in the United States and how sociologists examine them. We turned our focus to some specific social problems related to our increasing ecological challenges, such as environmental racism and environmental inequity. Then we examined the worldviews and actions that are currently shaping environmental social movements.

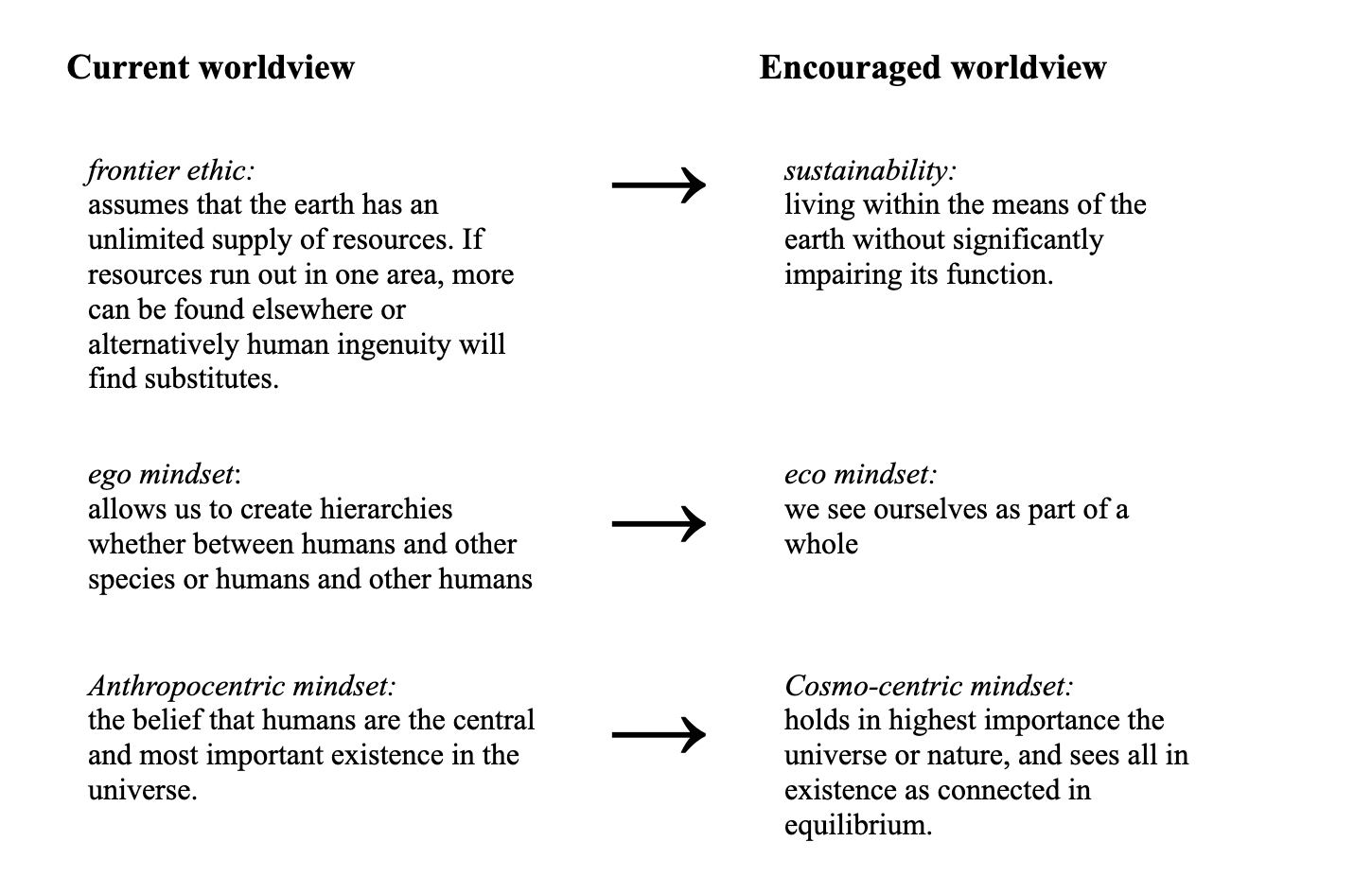

Figure 10.54 gives a summary of that discussion. There, you can see the current, dominant, worldviews and the worldviews that members of social-environmental movements encourage us to develop. They encourage us to replace an “ego” mindset with an “eco” mindset. They encourage us to replace frontier ethics with a sustainability worldview. Added to figure 10.54 is the anthropocentric view of life that was introduced in Chapter 9, which is encouraged to be replaced by a cosmocentric worldview. There are similarities among these calls for shifts in worldview. How would you describe the similarities that you see?

Finally, we took a close look at Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous-led environmental protection movements. Indigenous knowledge has greatly influenced the development of the Encouraged worldviews in figure 10.55. Indigenous-led environmental movements are protecting the natural world and, in turn, Indigenous ways of life that support human existence as environmental changes advance.

Review of Learning Outcomes

This chapter has offered you the opportunity to:

- Explain how sociologists identify the types and stages of social movements.

- Discuss sociological perspectives on social movements.

- Describe how environmental changes and our responses to those changes exacerbate inequity.

- Examine how environmental movements reshape perspectives and improve lived experiences for members of societies.

- Illustrate how environmental justice movements correct injustice and support social and environmental resilience.

- Explain the role and importance of Indigenous-led environmental movements in environmental justice.

Key Terms

alternative movements: the mobilization of large numbers of people focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behavior.

biocentrism: a philosophy that extends equal and inherent value to all living beings.

bureaucratization stage: a phase of social movements when the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically with a paid staff.

coalescence stage: a phase of social movements when people join together and organize to publicize the issue and raise awareness.

decline stage: a phase of social movements when people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or people no longer take the issue seriously.

emergence stage: a phase of social movements when people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge.

environmental inequity: the fact that low-income people and people of color are disproportionately likely to experience the impacts of environmental problems.

environmental justice: the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income concerning the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

environmental racism: a form of systemic racism created by policies and practices that deliberately target communities of color for residence in areas more vulnerable to disaster. It also includes the targeting of those residences for toxic waste disposal and the location of polluting industries.

environmental sustainability: the sociopolitical, scientific, and cultural practice of living within the means of the Earth without significantly impairing its function. Additionally, the conservation of natural resources and protection of global ecosystems are crucial for supporting health and wellbeing.

frontier ethic: a worldview that assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere, or alternatively, human ingenuity will find substitutes.

redemptive movements: mobilization of large numbers of people who are “meaning-seeking.” Their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals.

reform movements: mobilization of large numbers of people who seek to change something specific about the social structure.

resistance movements: mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure.

resource mobilization theory: a perspective that explains movement success in terms of the ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals.

revolutionary movements: mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to completely change every aspect of society.

Comprehension Check

Licenses and Attributions for Conclusion

Open Content, Original

“Conclusion” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 10.55. “Current Worldview and Encouraged Worldview” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Key terms, resource mobilization theory and revolutionary movements are taken from “Key Terms” in “Introduction to Social Movements and Social Change” of Introduction to Sociology 3e.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a form of systemic racism created by policies and practices that disproportionately force communities of color to live near toxic waste and airborne matter, burdening them with health hazards.

the fact that low-income people and people of color are disproportionately likely to experience various environmental problems.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, concerning the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.