10.3 Types of Social Movements

Social movements are major drivers of cultural change and social progress. Large-scale institutional changes that advance freedom or move the dial forward on social justice are rarely initiated by institutional leaders or political elites. Most social progress is instead the result of pressure applied from the bottom up by ordinary people who insist on change. They organize and engage in collective action that creates disorder outside the bounds of mainstream institutions.

These bottom-up actions make the participation of ordinary people possible. As people join efforts, it also becomes more probable that their actions will matter. So in turn, more people want to participate. Eventually, masses of individuals and organizations are represented, carrying out robust strategies online or in the streets. They express a groundswell of urgency that makes it impossible to ignore their calls to action and demands. This groundswell allows movements to push for systemic, structural, and cultural change. These are the dynamics of all social movements. However, between them, there’s a vast diversity that has been studied extensively by sociologists.

When considering social movements, the images that come to mind are often the most dramatic and dynamic. The Boston Tea Party; anti-war protesters putting flowers in soldiers’ rifles; hooded men posing as Guantanamo Bay prisoners to protest conditions there (figure 10.5). Or perhaps more violent visuals: burning buildings in Watts, Los Angeles; protesters fighting with police; a lone citizen facing a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square. But social movements also appear as less obvious and less dramatic series of actions and events. They defy the cultural standards of the dominant culture because they are hard to define, not linear, and don’t have one leader or spokesperson.

Sociologist David Aberle (1966) developed four categories that distinguish social movements based on what they want to change and how much change they want. He called them reformative, redemptive, revolutionary, and alternative.

Reform movements seek to change something specific about the social structure. Examples include antinuclear groups, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the Human Rights Campaign’s advocacy for marriage equality, and the DREAMers movement for immigration reform (figure 10.6). The DREAMers became prominent around 2000 when more than 1 million children and youths found themselves having migrated to the United States as children without any authorization and grew up without legal status. The name comes from the Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, national legislation proposed to provide a pathway to permanent residency and U.S. citizenship for qualified undocumented immigrant students.

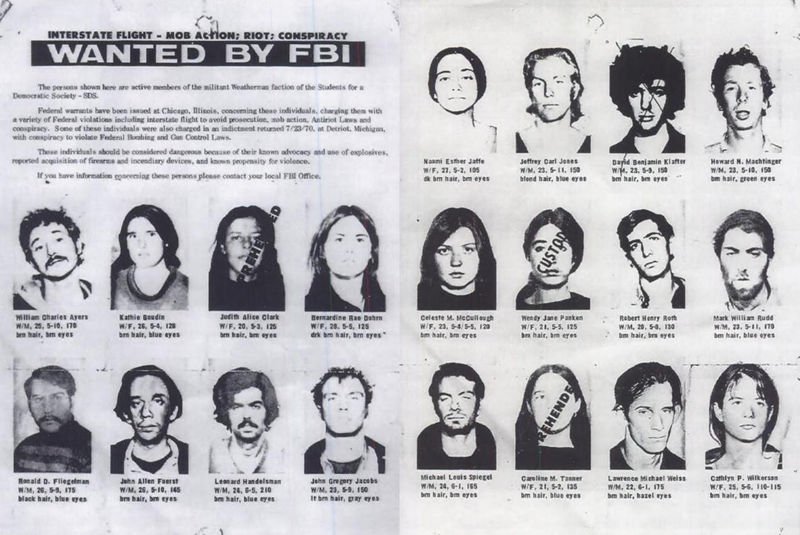

Revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of society. These include the 1960s counterculture movement, anarchist collectives, Texas Secede!, and the revolutionary movement associated with the group the Weather Underground (figure 10.7). The Weather Underground Organization was a famous far-left Marxist militant organization founded at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Active in the late 1960s and early 1970s, their political goal was to create a revolutionary party to overthrow the U.S. government in protest of its aggressive and colonialist policies around the world.

Redemptive movements are “meaning-seeking,” and their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals. Organizations pushing these movements include Heaven’s Gate, the Branch Davidians, and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, known colloquially as the Hare Krishna (figure 10.8). The Hare Krishnas hold a unique form of monotheistic core beliefs that are based on Hindu scriptures, the practice of vegetarianism, and the practice of Bhakti yoga. There are around 10 million followers worldwide.

Alternative movements are focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behavior. These include trends like transcendental meditation, macrobiotic dieting, and participation in the activities of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (figure 10.9). AA is a global peer-led organization that supports people in recovery from alcoholism.

Resistance movements seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure. The Ku Klux Klan, the Minutemen, the pro-life movement, and the American Indian Movement (AIM) fall into this category. AIM is an American Indian grassroots movement founded in 1968. Members work to resist systemic poverty, discrimination, and police brutality against American Indians. They also work on treaty rights, American Indian representation in education, and the preservation of Indigenous cultures. A more recently emerged Native American resistance movement is Idle No More. It started in 2012 as First Nations Peoples in Canada began to protest how the Canadian government was dismantling environmental protection laws (figure 10.10).

Other helpful categories that sociologists use to distinguish between types of social movements include type of change, targets, methods of work, and range.

Type of Change: A movement might seek change that is either innovative or conservative. A conservative movement seeks to preserve existing norms and values, such as a group opposed to genetically modified foods, while innovative movements want to introduce or change norms and values, like moving towards self-driving cars. The movement for marriage equality is an example of a movement seeking an innovative type of change (figure 10.11).

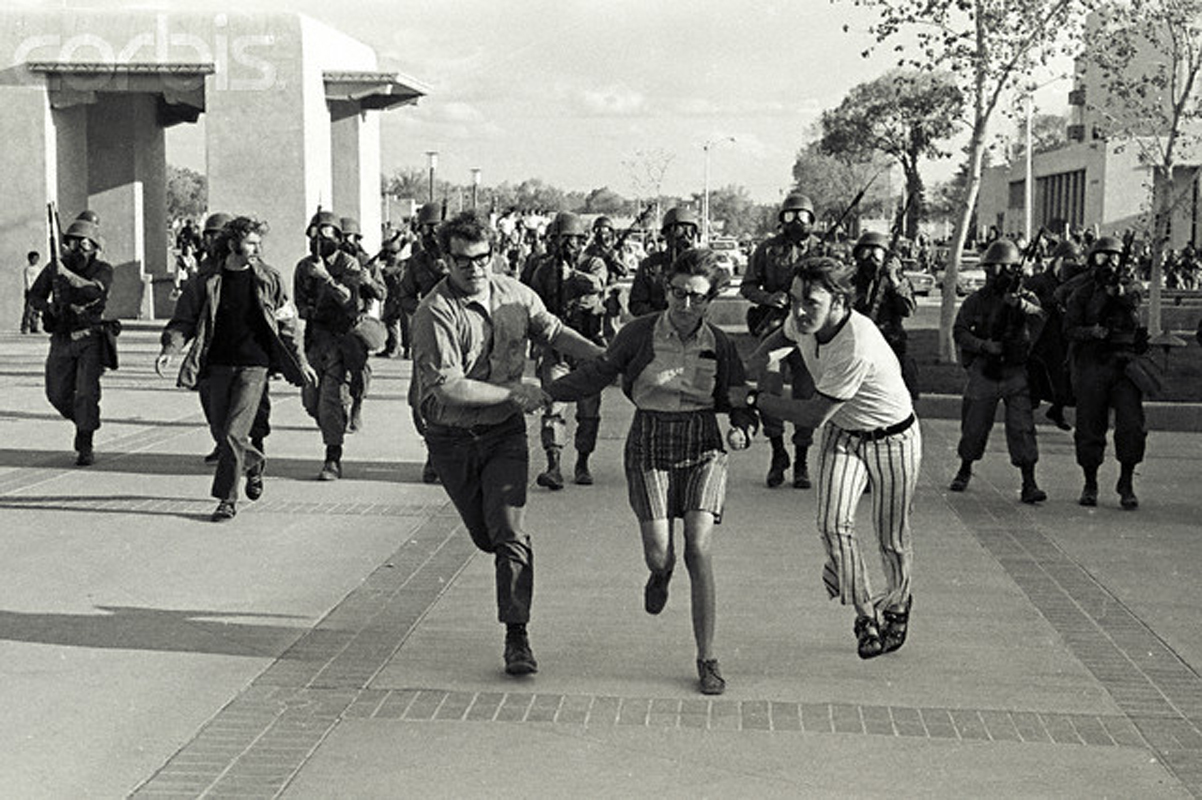

Targets: Group-focused movements focus on influencing groups or society in general—for example, attempting to change the political system from a monarchy to a democracy. An individual-focused movement seeks to affect individuals. The anti-Vietnam War movement targeted members of the U.S. government in an attempt to convince them to end U.S. involvement in the war (figure 10.12).

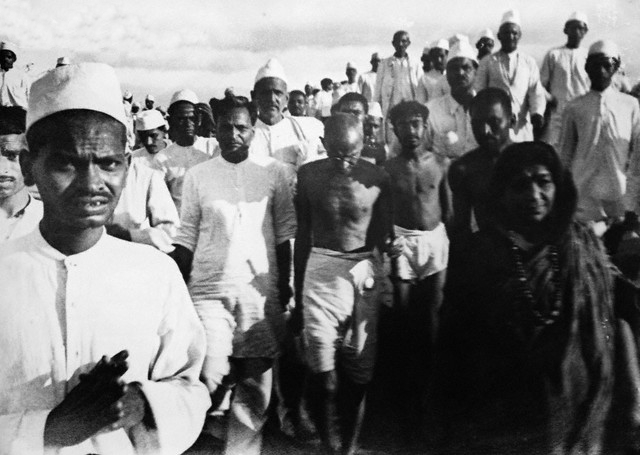

Methods of Work: Violent movements resort to violence when seeking social change. In extreme cases, violent movements may take the form of paramilitary or terrorist organizations. Peaceful movements utilize techniques such as civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance. Mahatma Gandhi is widely known for his nonviolent resistance, which garnered a mass following in the movements he led in Colonial India.

One campaign, known as the Salt March, protested laws imposed by the British government that were designed to support the monopolization of salt by the British East India Company. Taxation of salt and laws that made it illegal to collect and manufacture salt were a hardship for the poor of India. In 1930, Gandhi began a 24-day walking demonstration that included the breaking of those laws (figure 10.13).

Range: Global movements, such as political uprisings throughout the Arab world, have transnational objectives. National-level movements such as the push to end drunk driving tend to focus on federal policy to make change. Local movements focus on neighborhood, town, or city-level objectives, such as preserving a historic building or protecting a natural habitat. For example, the urban regreening movement works at the local (town or city) level. Members take action as environmental stewards by improving the quality and quantity of green spaces and by recognizing and preserving nature and biodiversity in cities (figure 10.14).

Licenses and Attributions for Types of Social Movements

Open Content, Original

“Types of Social Movements” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Types of Social Movements” is adapted from “21.2 Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology 3e, licensed under CC BY 4.0 and “Types and Stages of Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology Lumen/OpenStax. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, include elaboration on specific movements with photos.

Figure 10.5. “Close Guantanamo” by Debra Sweet is on Flickr and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.6. “The Dreamers Movement” by Molly Adams is on Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.7. “1970 FBI poster” is published on KeyWiki under the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3.

Figure 10.8. “Hare Krishna Street Show – Moscow, Russia, 2009” by Anneli Salo, on Wikipedia, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 10.9. “Alcoholics Anonymous Convention, 1990” by King County is on Flickr and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 10.10. “Statue of Christopher Columbus During George Floyd Protests” on Wikipedia, by Tony Webster, is licensed under CC BY 2.0 (left). “Idle No More” is on Flickr, by Daniela Kantorova, and licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 (right).

Figure 10.11. “A Marriage Equality Decision Day Rally” on Wikimedia Commons, by Elvert Barnes, is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.12. “May 1970, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA” is on Flickr by TommyJapan1 and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.13. “The Salt March on March 12, 1930” by an unknown author is on Wikipedia and in the public domain.

Figure 10.14. Pavement deconstruction image is created by Depave, published on the Depave Facebook page, used by permission, and licensed under CC BY 4.0 (right).

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.14. Logo of Depave is found on the Depave website and included under fair use (right).

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a state where "everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life.”

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

mobilization of large numbers of people who seek to change something specific about the social structure.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to completely change every aspect of society.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

mobilization of large numbers of people who are “meaning-seeking.” Their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals.

the mobilization of large numbers of people focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behavior.

mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.