10.4 Stages of Social Movements

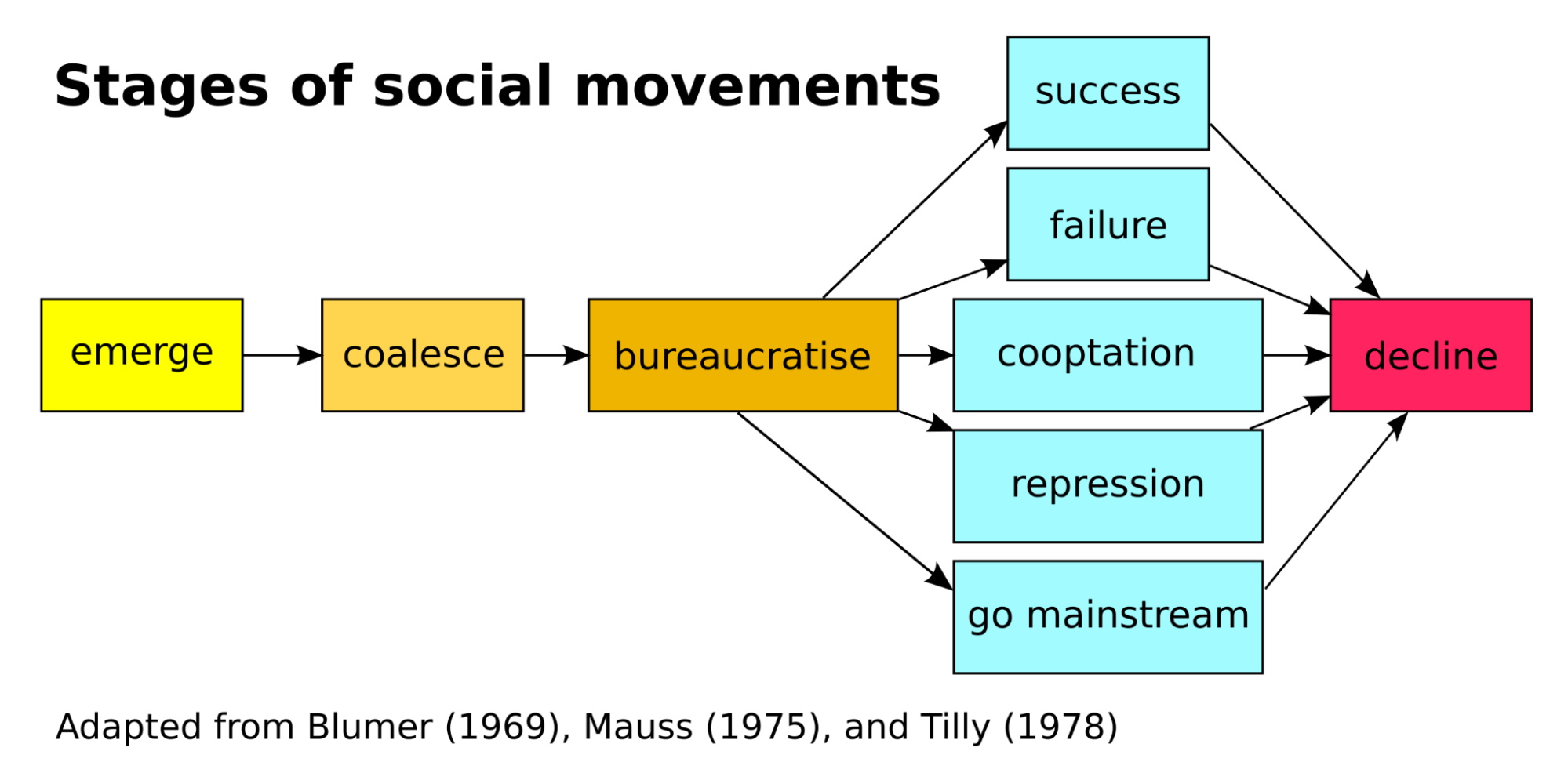

Sociologists also study the lifecycle of social movements—how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Each movement takes on a unique life cycle as strategies shift and the world responds. Herbert Blumer (1969) and Charles Tilly (1978) outline a four-stage process (figure 10.15). In the emergence stage, people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage, when people join together and organize to publicize the issue and raise awareness.

In the bureaucratization stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically with a paid staff. At this point, the movement can take several directions. It might successfully bring about the change it sought. Or it might result in failure to change the circumstances intended by members as people no longer take the issue seriously. It might be co-opted, it might meet repression, or it might go mainstream.

Beyond any of these five options, the movement will enter a decline stage, when people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or people no longer take the issue seriously.

Influence of Social Media

It is interesting to examine these stages by adding the role of social media to the analysis. Tarana Burke first used the phrase “Me Too” in 2006 on a major social media venue of the time, MySpace (figure 10.16). The phrase later grew into a massive movement when people began using it on Twitter to drive empathy and support regarding experiences of sexual harassment or sexual assault. Similarly, Black Lives Matter began as a social media message after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, and the phrase burgeoned into a formalized (though decentralized) movement in subsequent years. Today, social media is a widely used mechanism in social movements.

Social media has the potential to dramatically transform how people get involved in movements ranging from local school district decisions to presidential campaigns. Compared to movements of 20 or 30 years ago, social media can accelerate the emergence stages substantially. Issue awareness can spread at the speed of a click, with thousands of people across the globe becoming informed at the same time.

During the coalescence stage, social media can amplify the movement’s reach to find volunteers, publicize issues, and raise awareness. President Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign was a case study in organizing through social media. Using Twitter and other online tools, the campaign engaged volunteers who had typically not bothered with politics. Combined with comprehensive data tracking and the ability to micro-target, the campaign became a blueprint for others to build on.

In some cases, once a movement reaches the institutionalization stage, a formal organization might exist alongside the hashtag or general sentiment, as is the case with Black Lives Matter. At any one time, Black Lives Matter is essentially three things: a structured organization, an idea with deep and personal meaning for people, and a widely used phrase or hashtag. It’s possible that users of the hashtag are not referring to the formal organization. It’s even possible that people who hold a strong belief in Black Lives Matter do not agree with all of the organization’s principles or its leadership. And in other cases, people may be very aligned with all three contexts of the phrase.

Case Study: Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring

Occupy Wall Street (OWS) (figure 10.17) was a unique movement that defied some of the theoretical and practical expectations regarding social movements. However, it provides a good case study to examine Blumer and Tilly’s lifespan of social movements. Let’s look at how it emerged and coalesced, how globalization and the media influenced its reach, and whether or not it was a success or a failure.

Manuel Castells (2012) notes that the years leading up to the OWS movement had witnessed a dizzying increase in the disparity of wealth in the United States, stemming back to the 1980s. Wealth inequality (as we learned in Chapter 4) had become severe. The top 1 percent in the nation had secured 58 percent of the economic growth in that period for themselves, while real hourly wages for the average worker had increased by only 2 percent. The wealth of the top 5 percent had increased by 42 percent. The average pay of a CEO was at that time 350 times that of the average worker, compared to less than 50 times in 1983 (AFL-CIO 2014).

Many blamed the country’s leading financial institutions for the crisis. They were in trouble after many poorly qualified borrowers defaulted on their mortgage loans when the loans’ interest rates rose. The banks were eventually “bailed out” by the government with $700 billion of taxpayer money and dubbed “too big to fail.” According to many reports, that same year top executives and traders received large bonuses.

On September 17, 2011, the occupation began. About 1,000 protesters descended upon Wall Street, and up to 20,000 people moved into Zuccotti Park, only two blocks away, where they began building a village of tents and organizing a system of communication. The protest soon spread throughout the nation, and its members started calling themselves “the 99 percent.” More than a thousand cities and towns in the United States had OWS demonstrations.

As in most movements, OWS was sparked once a significant number of people reached a point of intolerance toward the status quo. As sociologist James C. Davies explained, when formerly prosperous people begin to have unmet needs and unmet expectations, they become disturbed and motivated to protest. Thus, change comes not from the very bottom of the social hierarchy but from somewhere in the middle (Davies 1962).

Many of the protesters were young students burdened with student loans and high tuition rates, facing uncertain futures due to the economic situation. For generations, residents of the United States had been able to expect that getting a college education would allow them to meet or exceed the economic class of their parents. However, students and former graduates were finding that reality no longer true. They blamed policy decisions and the financial systems as contributors to that shifting reality. This group, as well as others who had not attended college, found themselves in a new reality, working for very long hours for stagnating wages or subject to temporary work with no security.

While the nexus of the OWS movement occurred in the United States, globalization played a significant role in its inspiration, reach, and endurance. Once the movement was underway, protests resonated across the world, motivating thousands to voice their anger at financial and social inequality. Some protests merged with existing anti-government protests. In October 2011, demonstrations took place in more than 80 countries all under the name of a global “Day of Rage.”

Globalization also played a part in the origins of the OWS movement. Before the protests, on July 13, 2011, the Canadian-based organization Adbusters posted on its blog, “Are you ready for a Tahrir moment? On September 17th, flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street” (Castells 2012). The “Tahrir moment” was a reference to the Arab Spring, a series of pro-democracy, anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions that began in 2010 in response to corruption and economic stagnation.

The Arab Spring began after the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, a fruit and vegetable vendor in the town of Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia. Bouazizi had suffered extensive abuse by the local police because he was working without a permit. They would demand bribes, sometimes confiscating his merchandise or all he had earned in a day. On December 17, 2010, a police officer confiscated the scales he used to weigh his produce. He went to complain to the provincial government but was refused. Having reached a point of sheer desperation, as protest, Bouazizi set himself alight on the street outside, dying of his injuries two and a half weeks later (Lageman 2020).

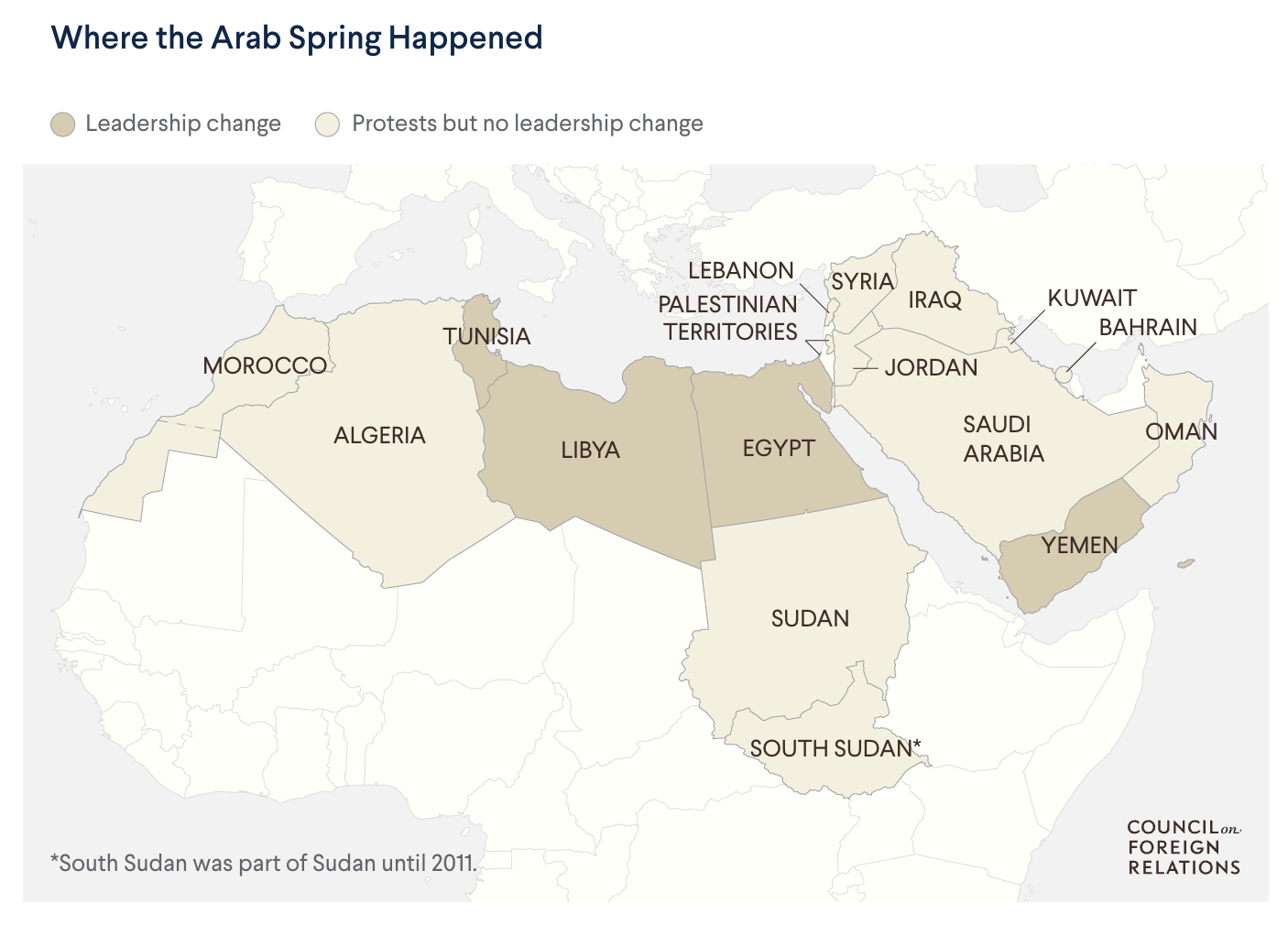

Bouazizi’s death sparked mass protests in Tunisia among a civilian population that had been experiencing extended economic hardship, lack of opportunity, and the corruption of their security personnel and government. The protests resulted in the then-dictator and Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali stepping down. Soon, protests spread throughout the Middle East and North Africa, including Bahrain, Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Egypt’s Tahrir Square in Cairo (figures 10.18 and 10.19), with other rulers deposed.

OWS was a reaction to the continuing financial chaos that resulted from the 2008 market meltdown; it was not a political movement. However, the Arab Spring was its catalyst, and there were similarities to the movements.

OWS baffled much of the public and certainly the media, leading many to ask, “Who are they, and what do they want?” Castells dubbed OWS “a non-demand movement: The process is the message.” Using Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and livestreamed videos, the protesters conveyed a multifold message with a long list of needed reforms and social change. They included addressing the rising disparity of wealth, the influence of money on election outcomes, our corporatized political system, political favoring of the rich, and rising student debt.

Both the Arab Spring and OWS were driven by mostly young, educated people whose promises and expectations were thwarted by corrupt, autocratic governments. The protesters exploited the power of social media to enhance communication. In an interview with the newsreel Al Jazeera, Ali Bouazizi shared that despite the evident dangers of criticizing the regime, he decided to publish a video on Facebook of protests in front of the provincial government building. “Of course, I was terrified when I posted that video.…But I felt I couldn’t back down now, for the sake of my children and family. This was a God-given chance, and I had to take it” (Lageman 2020).

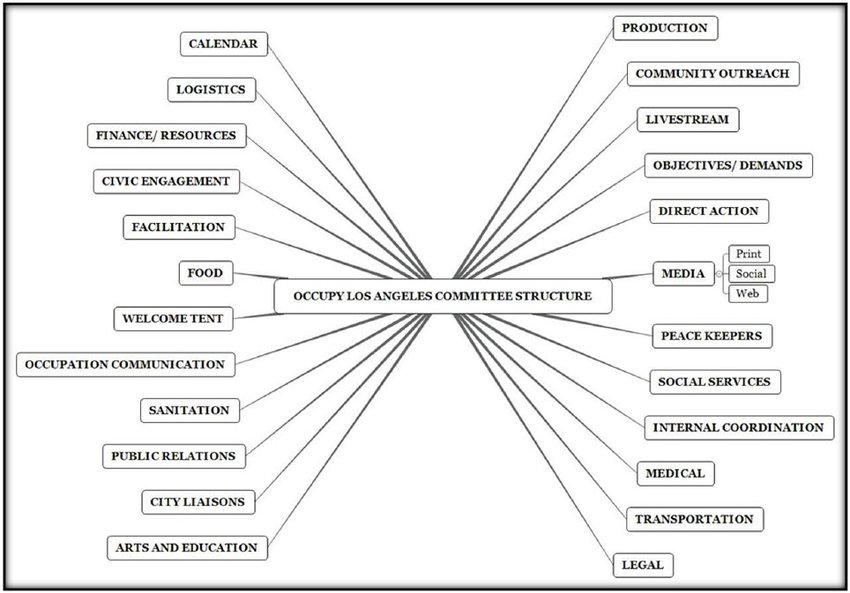

Following the life cycle prediction of Blumef and Tilly, OWS did not bureaucratize. It did not become a formal organization with paid staff, widely respected and recognized by the dominant culture. However, during the weeks of the protests, a formidable and complex organization was formed within many of the camps (figure 10.20).

What did OWS and the Arab Spring accomplish? Despite headlines at the time mocking OWS for lack of cohesion and lack of clear messaging, the movement is credited with bringing attention to income inequality and preferential treatment of financial institutions accused of wrongdoing. Many financial crimes are not prosecuted, and their perpetrators rarely face jail time. It is likely that the general population is more sensitive to those issues than they were before OWS and related movements made them more visible.

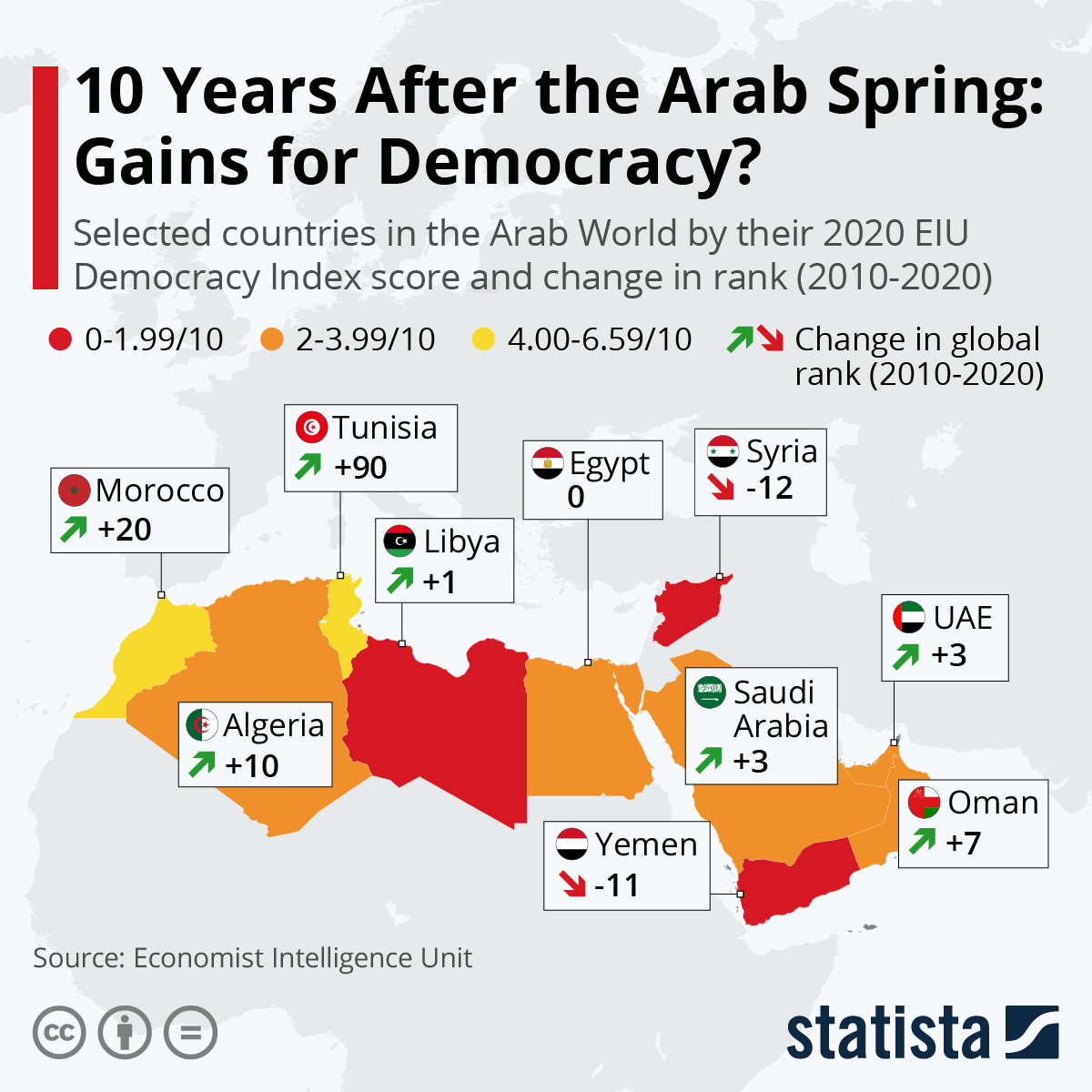

At first glance, from the lens of news and politics, the uprisings of the Arab Spring may appear to be a failure. But if we study the social changes experienced in Arab Spring-affected societies through a sociological lens, the story becomes more whole.

North Africa and Middle East Arab societies have redefined their political space since the Arab Spring. Protests emerged in Lebanon and Iraq. Largely peaceful mass demonstrations began across Algeria in 2019, opposing then-president Abdelaziz Bouteflika. They later demanded political reforms and further freedoms (figure 10.21).

Even in Egypt, which saw a return to severe authoritarianism after 2011, is seeing more protests. A majority of citizens are now taking action with more hope that those in power can be removed. Authorities now view protests and public demonstrations as more than a challenge to their authority. They are indicators of another potential uprising, or even a revolution (Adraoui 2021).

Has the United States changed the way it manages inequality? Certainly not with any immediate policy. In the United States, income inequality has generally increased. However, looking closer, there are lingering shifts. Astra Taylor and Jonathan Smucker believe that OWS helped usher in “a social-movement renaissance across a range of issues, including racial justice, climate change, debt cancellation, and organized labor” (Taylor and Smucker 2021).

They also point to the way OWS created space for a generation of organizers to develop strategic discipline and practice collective action. It also helped that generation better understand power within social structures and the importance of building institutions.

There are also evident shifts within some institutions. For example, a loan forgiveness initiative that became wide enough to be a movement focused on forgiving student loan debts for U.S. students (figure 10.22 [left]). And Jubilee 2000 was a campaign that led ultimately to the cancellation of more than $100 billion of debt owed by 35 of the poorest countries (Pettifor 2000) (figure 10.22 [right]).

The debt relief allowed countries to invest in poverty-reduction, health, and educational programs. The campaign also led to a global awareness of the immensity of the debt, helping activists challenge the corruption behind many debt-related practices (Pettifor 2000).

Licenses and Attributions for “Stages of Social Movements”

Open Content, Original

“Stages of Social Movements” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Stages of Social Movements,” except for “Case Study: Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring” is adapted from “21.2 Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology 3e, licensed under CC BY 4.0, and “Stages of Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology Lumen/Openstax, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include edits for brevity and context. Images of Tarana Burke added (figure 10.16). Preliminary stage changed to emergence stage to be consistent with infographic.

Figure 10.15. “Stages of Social Movements” is on Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

Figure 10.16. “Tarana Burke, Activist from New York City” is on Flickr by TED Conference and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (left).

“Case Study: Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring” is adapted from “Introduction to Social Movements and Social Change” and “Social Movements” sections of Chapter 21, “Social Movements and Social Change” found in Introduction to Sociology 3e and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include content added on Mohammed Bouazizi, globalization, long-term impacts of the movements, images, map: “Where the Arab Spring Happened,” “Committee structure of the Occupy Los Angeles General Assembly,” and “Ten Years After the Arab Spring” (Figures 10.19, 10.20, 10.21).

Figure 10.17. “Occupy Wall Street Protester” is on Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.18. “Tahrir Square Protest” is on Wikimedia Commons, by Jonathan Rashad and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.20. “The Committee Structure of the Occupy Los Angeles General Assembly” by Joan Donovan is licensed under CC BY-NC.

Figure 10.21. “Ten Years After the Arab Spring: Gains for Democracy?” by Statista is licensed under CC BY ND.

Figure 10.22. “Members of OccupySF” is on Flickr, by jjinsf94115, and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (left). “Cancel Greek Debt” is on Flickr, by Global Justice Now, and licensed under CC BY 2.0 (right).

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.16. “Unbound Book Cover” is included under fair use (right).

Figure 10.19. “Where the Arab Spring Happened” by Council on Foreign Relations is included under fair use.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a phase of social movements when people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge.

a phase of social movements when people join together and organize to publicize the issue and raise awareness.

a phase of social movements when the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically with a paid staff.

a phase of social movements when people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or when people no longer take the issue seriously.

a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities.

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.