10.5 Perspectives on Social Movements

A branch of the study of social movements is social movement theory. Thinkers in this field attempt to explain many phenomena, such as: Why does social mobilization happen? How does it manifest, and what are the potential consequences? Why do certain people form or become members of a social movement? And how do people behave within movements? The following three theories are but a few of the many classic and modern theories developed by social scientists to explain how social movements function.

Resource Mobilization

McCarthy and Zald (1977) define resource mobilization theory as a way to explain movement success in terms of the ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals. Resources are primarily time and money, and the more there is of both, the greater the power of organized movements. Numbers of social movement organizations, which are single social movement groups with the same goals, constitute a social movement industry. Together they create what McCarthy and Zald (1977) refer to as “the sum of all social movements in a society.”

An example of resource mobilization is the activity of the civil rights movement between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s. Social movements had existed before, notably the women’s suffrage movement and a long line of labor movements. The civil rights movement had also existed well before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. Her arrest triggered a public outcry that led to the famous Montgomery bus boycott, which launched what we now think of as the “civil rights movement” (Schmitz 2014).

Mobilization had to begin immediately. Boycotting the bus made other means of transportation necessary, which was provided through carpools. Churches and their ministers joined the struggle, and the protest organization In Friendship was formed as well as the Friendly Club and the Club From Nowhere. A social movement industry was growing.

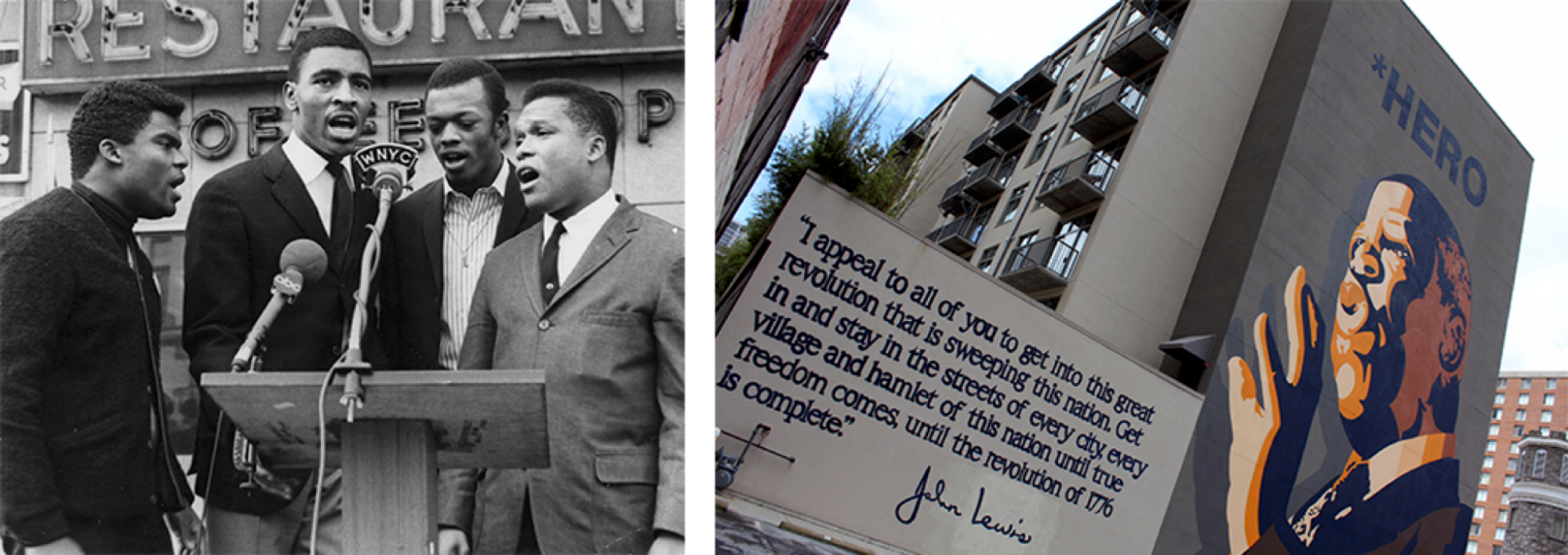

Martin Luther King Jr. emerged during these events to become the charismatic leader of the movement, gaining respect from elites in the federal government. Mobilization was then aided by even more emerging social movement organizations, such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) (figure 10.23) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), among others.

With each of these steps, a social movement sector developed, and several social movement industries developed. Although the movement in that period was an overall success and laws were changed (if not attitudes), the “movement” continues. Several organizations that began in the 1950s and 1960s exist today. So do struggles to keep the gains that were made, even as the U.S. Supreme Court has recently weakened the Voting Rights Act of 1965, once again making it more difficult for Black Americans and other minorities to vote.

Political Opportunity Theory

Another influential perspective is political opportunity theory. According to this view, social movements are more likely to arise and succeed when political opportunities for their emergence exist or develop. For example, when a government that previously was repressive becomes more democratic or when a government weakens because of an economic or foreign crisis (Snow and Soule 2010).

When political opportunities of this kind exist, discontented people perceive a greater chance of success if they take political action, and so they decide to take such action. As Snow and Soule (2010:66) explain, “Whether individuals will act collectively to address their grievances depends in part on whether they have the political opportunity to do so.” Applying a political opportunity perspective, one important reason that social movements are so much more common in democracies than in authoritarian societies is that activists feel freer to be active without fearing arbitrary arrests, beatings, and other repressive responses by the government.

New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory was developed by European social scientists and attempts to explain the surge of postindustrial and postmodern movements. It’s a perspective that revolves around understanding contemporary movements overall, as they relate to politics, identity, culture, and social change. The primary difference is in their goals, as the new movements focus not on issues of materialistic qualities such as economic well-being but rather on issues related to civil and human rights.

Some of these more complex interrelated movements include ecofeminism and the transgender rights movement. Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism that focuses on the patriarchal society as a source of environmental problems. Because both women and nature have been devalued, we are seeing harmful conditions for both the planet and women. The transgender rights movement promotes the legal status of transgender people and the elimination of discrimination and violence against transgender people (figure 10.24). Sociologist Steven Buechler (2000) suggests that we should be looking at the bigger picture in which these movements arise—shifting to a macro-level, global analysis of social movements.

The movement to legalize marijuana is an example of a phenomenon that new social movement theory examines. The marijuana legalization movement focuses on changing the culture of the United States by transforming the legality of a substance from something illegal into something people could legally use in their everyday lives. As marijuana is made legal, those actions create a new norm for what is considered deviant in society.

Social Movements in Theory and Action

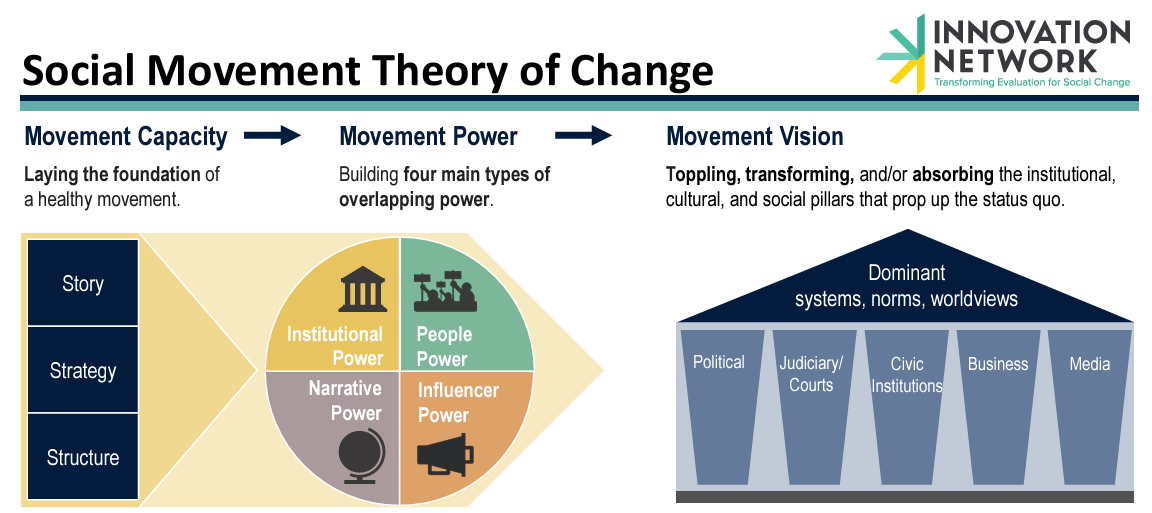

Sometimes social scientists contribute to theories of change for specific movements. These theories are often based on observations of what makes social movements effective. For example, Innovation Network’s Social Movement Learning Project outlines a map for creating change and for evaluating change through social movements. Take a look at their visual in figure 10.25. They describe how movement capacity, movement power, and movement vision are all necessary for change. Similarly, the map outlines how institutional power, influencer power, people power, and narrative power are all key elements of successful social movement-making:

- Institutional power is the power to influence who makes decisions and how decisions are made.

- Influencer power is the power to develop, maintain, and leverage relationships with people and institutions with influence over and access to critical social, cultural, or financial resources.

- People power is the power to build, mobilize, and sustain large-scale public support.

- Narrative power is the power to transform and hold public narratives and ideologies and limit the influence of opposing narratives.

The basic sociology of social movements includes an examination of the types and stages of social movements and analyzes social movements through the lens of theoretical perspectives. The rest of this chapter will explore the social movements associated with the environmental crisis. We’ll begin by exploring how sociology observes our environmental challenges so we can better understand the social response.

Licenses and Attributions for Perspectives on Social Movements

Open Content, Original

“Perspectives on Social Movements” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Resource Mobilization” is adapted from “Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology Lumen/OpenStax, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Images added.

Figure 10.23. “Members of the SNCC Freedom Singers” is on Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0 (left). “Mural in Honor of Civil Rights Hero John Lewis” is on Flickr under CC BY 2.0 (right).

“Political Opportunity Theory” is adapted from “Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“New Social Movement Theory” is adapted from “Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements” in Introduction to Sociology Lumen/OpenStax, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Minor edits made and image added.

Figure 10.24. “Transgender Day of Visibility in Melbourne (2023)” is on Flickr, by Matt Hrkac and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.25. “Social Movement Theory of Change” is found at Innovation Network and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a perspective that explains social movements’ success in terms of their ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals (3e)

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.