10.7 Shifts in Perspective and Practice

Movements for social justice and movements for protecting the environment have tended to exist independently of each other. However, more recently, as a result of our heightened environmental crisis, movements are arising that combine concerns of social inequity and the environment. This merging of movements represents a significant shift in perspective. In her TED Talk, Tania Roa expressed the values behind that shift this way:

When we separate humans from nature, we perpetuate the idea that we are…superior to other species, when in reality we are just as much a part of natural cycles and the Earth’s ecosystems as every other creature. It’s time we shift our mindset from compartmentalizing different causes to a more holistic perspective. Then, we can combine efforts to protect all people by addressing environmental injustices, and all living things (“How to Protect People and Planet” 2023).

In this section, we’ll look at some ways that perspectives are shifting to support social movements that encourage better care for the planet and better lived experiences for humans. But first, we’ll look at the influence that Indigenous wisdom has on these shifts.

Indigenous Wisdom

The traditions, languages, and beliefs of Indigenous Peoples vary tremendously across the world. However, there is a common worldview among Indigenous communities: that all parts of our ecosystem are connected and that humans, animals, plants, air, and rocks are dependent on one another for survival and ecological health. Indigenous lifeways represent traditions of living in balance with the natural world by preserving nature, using nature’s gifts in moderation, and respecting the interdependence of all living things.

For example, we can turn to the perspective of members of the Haudenosaunee nations. (The Haudenosaunee confederation consists of the five nations: Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, Onondaga, and Oneida. They follow the “Law of the Seventh Generation,” which takes into consideration those who are not yet born but who will inherit the world. The Haudenosaunee Confederation [Website] explains:

In their decision making Chiefs consider how present day decisions will impact their descendants. Nations are taught to respect the world in which they live as they are borrowing it from future generations (“Values” 2023).

Watch this 2-minute video, “The Relationship Between Humans and Nature” [Streaming Video] (figure 10.36). As you do, take note of a couple ideas: How do members of the Haudenosaunee Confederation view their relationship with the earth? And how did the Haudenosaunee people influence the U.S. Constitution? What teachings were omitted?

The holistic values and lifeways of the Haudenosaunee people and other Indigenous communities of North America have been conveyed via oral histories for centuries. They have been teaching those practices to the Western world since first encountering Europeans. The current shifts in the social-ecological perspectives of dominant North American culture reflect longstanding Indigenous values that hold society and nature as equal partners.

Biocentrism

One of those shifts relates to how humans interact in practice with the land and its offerings. Early European settlers in North America lived with an ethic that supported claiming land and rapidly consuming its natural resources (figure 10.37). After they depleted one area, they moved westward to new territory. This frontier ethic assumed that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere, or it was assumed that human ingenuity would find substitutes. This attitude sees humans as masters who manage the planet. The frontier ethic is completely human-centered, for only the needs of humans are considered.

Most industrialized societies have based their success on population and economic growth, assuming that infinite resources exist to support continued growth indefinitely. In fact, as we discussed in Chapter 4, it is common for economic growth to be considered as a measure of how well a society is doing. The late economist Julian Simon (1932–1998) suggested that (in his lifetime) life on earth had never been better and that population growth means more creative minds to solve future problems and give us an even better standard of living. In many ways, this ethic remains in dominant U.S. culture. However, now that the human population has passed 8 billion and few frontiers are left, many are beginning to question how well this supports society.

Aldo Leopold, a wildlife natural historian and philosopher in the United States (figure 10.38), advocated for a perspective in contrast to the frontier ethic. He introduced biocentrism to the conservation movement. It’s a philosophy that extends equal and inherent value to all living beings. At its core, biocentrism mimics Indigenous teachings.

However, Leopold translated those teachings to the Western world of law and ethics. He suggested that humans have always considered land as property, just as ancient Greeks considered slaves as property. He believed that mistreatment of land (or of slaves) makes little economic or moral sense, much as today, the concept of slavery is considered immoral. All humans are merely one component of an ethical framework.

Leopold suggested that land be included in an ethical framework, calling this the “land ethic”:

The land ethic simply enlarges the boundary of the community to include soils, waters, plants and animals; or collectively, the land. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow members, and also respect for the community as such (Leopold 1949).

Leopold maintained that our relationship with nature must be based upon more than just economic necessity. Species with no discernible economic value to humans may be an integral part of a functioning ecosystem. The land ethic respects all parts of the natural world regardless of their utility, and decisions based upon that ethic result in more stable biological communities.

Cosmocentrism

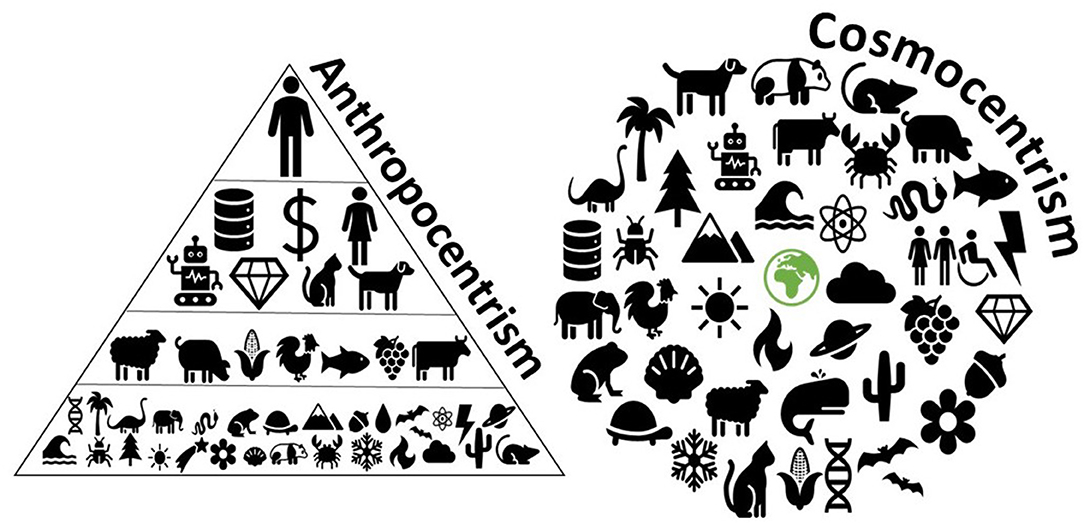

Another emerging shift in perspective is related to anthropocentrism, a concept we introduced in Chapter 9. Anthropocentrism is the belief that humans are the central and most important existence in the universe. There is a considerable change afoot with this paradigm, as many are encouraging it to be replaced by one that supports better care for both the planet and humans.

Cosmocentrism is a worldview that instead puts the planet at the center of our existence. It’s an acknowledgment that the world is a web of interrelationships among all beings (human, animal, plant, rock, etc.) that share the same level of hierarchy. Figure 10.39 illustrates the contrast between these two points of view.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a botanist, author, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation (Optional: Read more about the Potawatomi Nation [Website].) She adds more insight to this perspective in her book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants:

In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top—the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation—and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as “the younger brothers of Creation.”

We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn—we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance. Their wisdom is apparent in the way that they live. They teach us by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out (Kimmerer 2103:9).

Cultural historian Thomas Berry (1914–2009) was integral in introducing the concept of cosmocentrism to the field of conservation. According to his biography, he “urged humans to recognize their place on a planet with complex ecosystems in a vast evolving universe. He sought to replace the modern alienation from nature with a sense of intimacy [with other species] and responsibility [to protect and preserve them]” (The Thomas Berry Foundation, 2024).

Environmental Sustainability

A number of movements evolved from these shifts in ethics and perspective. One is centered around the notion of environmental sustainability. At its core, sustainability is a worldview that Indigenous Peoples have lived and practiced for centuries. It’s estimated that from around 1000 BC to 1000 CE, Indigenous communities in North America have applied what we now call sustainable agriculture (Minderhout 2009).

Sustainability proponents see the Earth as having limited resources and strive to put limits on human activities (e.g., uncontrolled resource use) that may adversely affect the natural world. A sustainable ethic assumes humans must use and conserve resources in a manner that allows their continued use in the future.

This value system also assumes that we are affected by natural laws and exist as part of the natural world. We suffer when the health of a natural ecosystem is impaired. Therefore, it is best that we live as part of the Earth, share the Earth’s resources with other living things, maintain the integrity of natural processes, and cooperate with nature rather than attempting to be managers of it.

Now, outside of Indigenous communities, sustainable and organic methods of farming have become an integral component of many government, commercial, and nonprofit research efforts, and it is beginning to be woven into agricultural policy. A recent framework for sustainable agriculture is regenerative agriculture, a set of farming and grazing practices that reverse climate change by rebuilding soil organic matter and restoring degraded soil biodiversity. This results in both carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere and improving the water cycle (figure 10.40). (Optional: Watch this 7-minute video, “What Is Regenerative Agriculture?” [Streaming Video]. What do you hear farmers share about its origins and what it means to them?)

Going Deeper

For more information about the Haudenosaunee Confederation [Website], see their website and this 2:38-minute video, “The Haudenosaunee” [Streaming Video].

For more information on the value of restorative practices, read “Climate Healing: Allying with the Ecosystem to Restore Natural Hydrological and Atmospheric Cycles” [Google Doc].

In this final podcast, Tracing the Roots of the Climate Crisis, “Chapter 4: Dreams” [Podcast], Ben Cushing reflects on the dreams we have as a society and their consequences (figure 10.41). For example, the American Dream is built in the context of colonial settlement and capitalist exploitation. It has created many of our crises today. The solutions to our problems will have to come from outside the framework of modernity and capitalist Eurocentric culture.The good news is that there are multiple transformative dreams taking root and flourishing. OWS modeled a radically democratic process and invited people to understand themselves and others in another way. Black Lives Matter built networks of local community members and organizations and fostered community ties. Indigenous-led social movements are focused on being in relation with one another and the earth. In this time of unprecedented crisis, how can we cultivate our capacity to dream for transformation? (Cushing 2021).

Licenses and Attributions for Shifts in Perspective and Practice

Open Content, Original

“Shifts in Perspective and Practice” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Cosmocentrism” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Biocentrism” is adapted from “1.4 Environmental Ethics” in Environmental Biology by Matthew R. Fisher and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Photos added.

Figure 10.37. American Progress by John Gast is found on Wikipedia and in the public domain.

Figure 10.38. “Aldo Leopold with Quiver and Bow Seated on Rimrock Above the Rio Gavilan” is on Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The first two paragraphs of “Environmental Sustainability” are adapted from Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 10.39. “Ego vs. Eco Anthropocentrism vs. Cosmocentrism” by J. Gonzalez Cruz and L.J. Lucero in Reconceptualizing Urbanism: Insights from Maya Cosmology is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.41. Summary adapted from transcript of, and Tracing the Roots of the Climate Crisis, “Chapter 4: Dreams” is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.36. Clickable image to “The Relationship Between Humans and Nature” is found on the same PBS Learning Media page and published here under fair use.

Figure 10.40. Screenshot from, and video, “What Is Regenerative Agriculture?” is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a state where "everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life.”

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

a worldview that assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere or alternatively, human ingenuity will find substitutes.

a philosophy that extends equal and inherent value to all living beings.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the worldview that makes humans central to decisions about ethics and daily life. It is built from the belief that humans are the most important existence in the universe.

the sociopolitical, scientific, and cultural practice of living within the means of the Earth without significantly impairing its function. Also: the conservation of natural resources and protection of global ecosystems to support health and wellbeing.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.