2.6 Society and the Natural Environment

At first glance, the environment does not seem to be a sociological topic. The natural and physical environment is something that meteorologists, oceanographers, and other scientists should study, not sociologists. However, the environment is very much a topic for the sociological study of social change for at least five reasons:

- Human activity is the cause of our worst environmental problems. Like many human behaviors, this activity is a proper topic for sociological study.

- Environmental problems significantly impact people, as do the many other social problems that sociologists study.

- Solutions to our environmental problems require changes in economic and environmental policies, and the potential impact of these changes depends heavily on social and political factors.

- Many environmental problems reflect inequality based on social class, race, and ethnicity. As is the case with many issues in our society, low income people and people of color often fare worse when it comes to the environment.

- Efforts to improve the environment, often called the environmental movement, constitute a social movement and are worthy of sociological study.

Human-made impacts on the environment have been discussed for many decades. Social and scientific leaders from all walks of life have also discussed ways to lessen humans’ effects on the environment and worked to understand how our changing environment impacts humans and societies.

Fifty years ago, in 1972, the first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment took place in Stockholm, Sweden. It resulted in what is often seen as the first step toward a global understanding of the importance of a healthy environment for people and the development of international environmental law. In 2021, the United Nations held the conference Stockholm+50: A Healthy Planet for the Prosperity of All—Our Responsibility, Our Opportunity to provide leaders with an opportunity to draw on the 50 years of multilateral environmental action to do what is needed to secure a better future on a healthy planet (figure 2.23).

Optional: Watch this 3:10-minute video, “Stockholm, 1972 – When Environmental Protection Was Born” [Streaming Video] (figure 2.23) for a history of those discussions, as well as a look at the efforts being implemented at the global level to support human existence in our changing environmental world. As you do, what initiatives do you see have been put in place to serve society facing environmental risks?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9zOSRqa-h3Q&t=185s

Environmental Sociology

So many sociologists study the environment that their collective study makes up a subfield in sociology. Environmental sociology is the study of the interaction between human behavior and the natural and physical environment. Environmental sociology assumes “that humans are part of the environment and that the environment and society can only be fully understood in relation to each other” (McCarthy and King 2009:1). An underlying tenet in the field of environmental sociology is that people are responsible for the world’s environmental problems. Therefore, we have both the ability and the responsibility to address them.

Environmental sociologists further our understanding of how society interacts with and impacts the environment in a number of arenas. For example, their research might focus on how people’s opinions and values shape their relationship to the environment and their environmental behaviors. Or research might be related to how human behavior drives climate change. Environmental sociologists might also study how social structure affects climate change (such as how politics in the corporate sector relates to emissions.) As we’ll cover well in this text, studying the environment through a sociological lens also includes making inquiries about climate justice across diverse experiences, and the effects of climate change on our relationship to nonhuman species (Nagel, Dietz, and Broadbent 2010).

Global Climate Change and Disasters

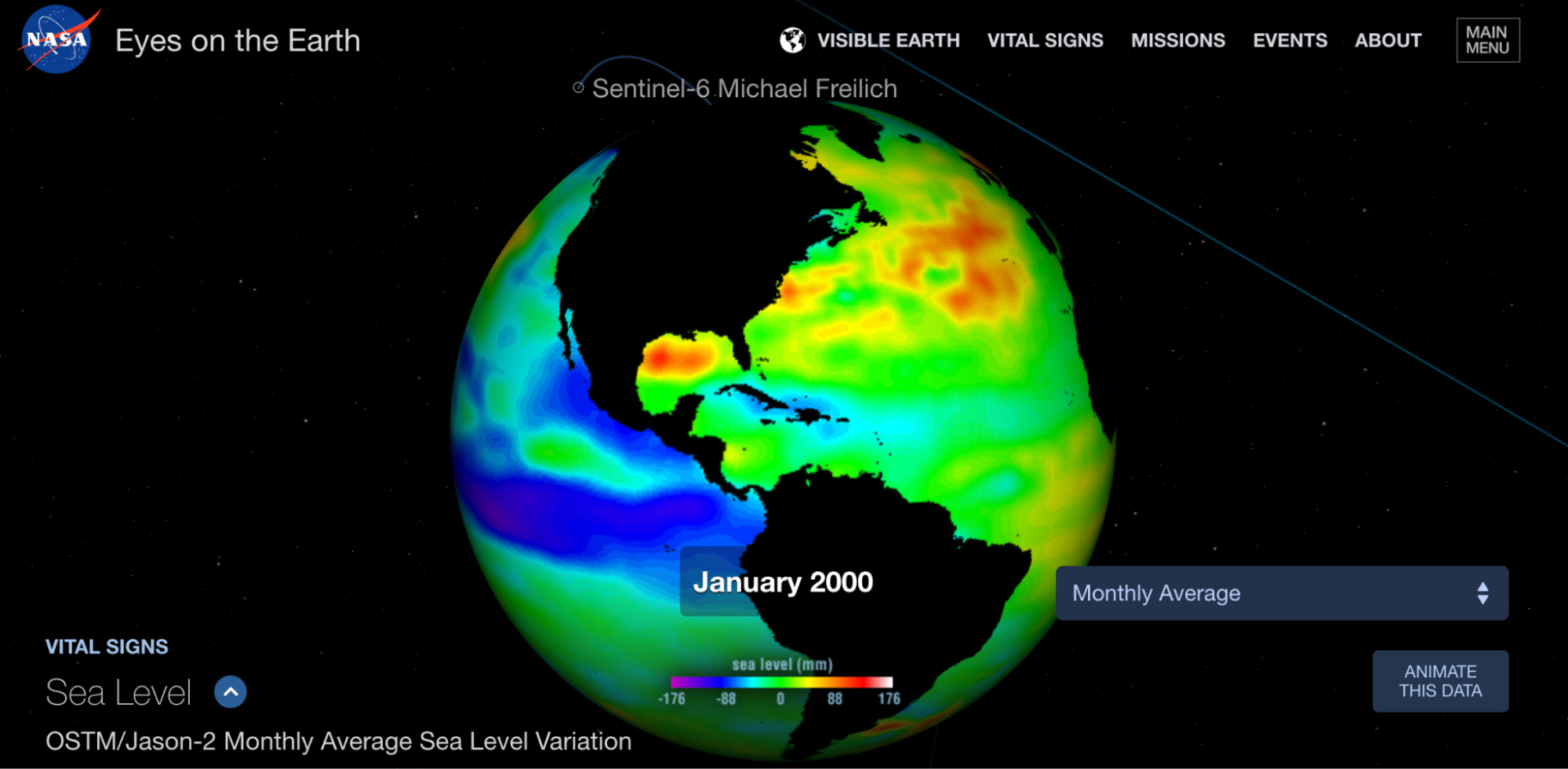

One of the most pressing issues we face is the rate of global climate change, the long-term shifts in temperatures due to human activity and, in particular, the release of greenhouse gases into the environment. Climate change is especially affecting the ecology of the Earth’s polar regions and ocean levels throughout the planet. Take a look at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) webpage on global sea levels [Website] (figure 2.24). You can also find animated data on other climate-related topics there. What have NASA’s sea level satellites revealed about global sea level changes over the last 30 years?

NASA provides some interpretation of these data:

…scientists estimate that every …1 inch of sea level rise translates into …8.5 feet of lost beachfront lost along the average coast. It also means that high tides and storm surges can rise even higher, bringing more coastal flooding (“Tracking 30 Years of Sea Level Rise” n.d.).

Over the past 50 years, climate change has prompted an increase in extreme weather and caused a surge in natural disasters. There are an increasing number of record-breaking weather phenomena, from the number of Category 4 hurricanes to the amount of snowfall in a given winter. In addition to the lives lost and people displaced, these extremes can cause immeasurable damage to crops and property.

Climate change threatens to produce a host of other problems, including increased disease transmitted via food and water, and malnutrition resulting from decreased agricultural production and drought. All these problems have been producing, and will continue to produce, higher mortality rates across the planet.

Climate change is a deeply controversial subject despite decades of scientific research and a high degree of scientific consensus that supports its existence. Until relatively recently, the United States was very divided on the existence of climate change as an immediate threat, as well as whether or not human activity causes or contributes to it. Now it appears that the United States has joined the ranks of many countries where citizens are concerned about climate change.

Research conducted in 2020 and 2021 indicated that at least 60 percent of United States residents believe climate change is a real and immediate threat (Flynn and Yamasumi 2021; Bell and Baaumann 2023). Citizens are also more supportive of clean energy and participating in international efforts, such as the Paris Climate Accord and the United Nations Climate Change Conferences.

What has changed these opinions? It may be that younger people are more represented in these polls, and they tend to support climate change initiatives. It may be that the continued severity of weather and the costly and widespread impact have become more difficult to ignore. It also may be that green and renewable energy sources are more prevalent, available, and visible to the public (figure 2.25).

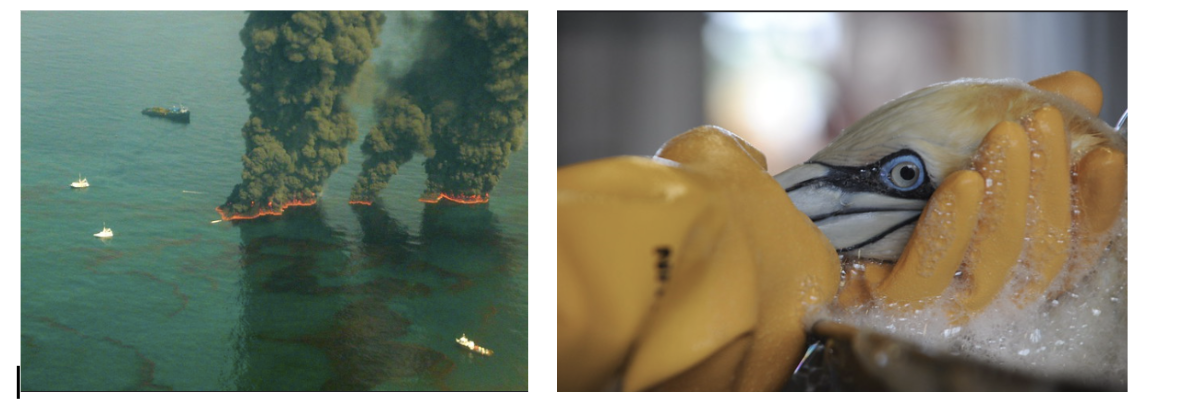

We know that changes in the natural environment lead to changes in society itself. We see the clearest evidence of this when a major accident or natural disaster strikes. The Deepwater Horizon disaster illustrates this phenomenon well. In April 2010, an oil rig operated by BP, an international oil and energy company, exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, creating what many observers called the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history. Its effects on the ocean, marine and animals will be felt for decades to come, as will the economies of states and cities affected by the oil spill (figure 2.26). As climate change is related to the extraction of resources, opinions may also be changing due to the effects of man-made disasters associated with extraction projects.

Environmental Health

Environmental sociology intersects with the study of environmental health. Environmental health is concerned with preventing disease, death, and disability by reducing exposure to adverse environmental conditions and promoting behavioral change. It focuses on the direct and indirect causes of diseases and injuries. Figure 2.27 gives a snapshot of health and safety issues and their environmental determinants, or the environmental factors that contribute to them.

| Underlying Determinants | Possible Adverse Health and Safety Consequences |

|---|---|

| Inadequate water (quantity and quality), sanitation (wastewater and etcetera removal), and solid waste disposal, improper hygiene (hand washing) | Diarrheas and vector-related diseases (e.g., malaria, schistosomiasis, dengue fever) |

| Improper water resource management (urban and rural), including poor drainage | Vector-related diseases (e.g., malaria, schistosomiasis) |

| Crowded housing and poor ventilation of smoke | Acute and chronic respiratory diseases, including lung cancer (from coal and tobacco smoke inhalation) |

| Exposures to vehicular and industrial air pollution | Respiratory diseases, some cancers, and loss of IQ in children |

| Population movement and encroachment, and construction, which affect the feeding and breeding grounds of vectors, such as mosquitos | Vector-related diseases (e.g., malaria, schistosomiasis, and dengue fever); may also help spread other infectious diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, Ebola fever) |

| Exposure to naturally occurring toxic substances | Poisoning (e.g., from arsenic, manganese, and fluorides) |

| Natural resource degradation (e.g., mudslides, poor drainage, erosion) | Injury and death from mudslides and flooding |

| Climate change, partly from combustion of greenhouse gases in transportation, industry, and poor energy conservation in housing, fuel, commerce, industry | Injury/death from extreme heat/cold, storms, floods, and fires. Indirect effects: spread of vector-borne diseases, aggravation of respiratory diseases, population dislocation, water pollution from sea level rise, etc. |

| Ozone depletion from industrial and commercial activity | Skin cancer, cataracts. Indirect effects: compromised food production, etc. |

As climate change advances, environmental sociologists generally expect the underlying determinants in the table to become more prevalent. Many work to tap resources inside and outside the healthcare system to help improve health outcomes.

Emerging Diseases

Emerging and re-emerging diseases are infectious human diseases whose occurrence has substantially increased or threatens to increase in the near future. COVID-19 is our era’s most globally devastating example. Other examples of emerging and re-emerging diseases include the Ebola virus, West Nile virus, Zika virus, sudden acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1 influenza, swine and avian influenza, and HIV. The 2014 Ebola epidemic was the largest Ebola outbreak in history, with over 28,000 cases and 11,302 deaths. The outbreak affected the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Liberia, the Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Uganda. The HIV/AIDS epidemic has spread with ferocious speed and has infected more than 60 million people worldwide.

A variety of environmental factors may contribute to the re-emergence of diseases, including temperature, moisture, and human food or animal feed sources. It seems likely that a wide variety of infectious diseases have affected human populations for thousands of years, emerging when the environmental conditions were favorable.

Expanding human populations have increased the potential for transmission of infectious diseases due to the increased likelihood of humans being in “the wrong place at the right time.” Natural disasters or political conflicts can add to the potential for transmission. Global travel also increases the potential for a disease carrier to transmit infection thousands of miles away in just a few hours.

There’s a wealth of discussion regarding how COVID-19 has affected us socially. But have you considered if the transmission of COVID-19 is related to how we interact with the environment? Scientific American outlines how human encroachment into natural areas and wildlife habitats brings us into closer contact with animals and plants that may harbor diseases, increasing the likelihood of transmission to humans:

…a number of researchers today think that it is actually humanity’s destruction of biodiversity that creates the conditions for new viruses and diseases like COVID-19.…In fact, a new discipline, planetary health, is emerging that focuses on the increasingly visible connections among the well-being of humans, other living things, and entire ecosystems.

We cut the trees; we kill the animals or cage them and send them to markets. We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it (Vidal 2020).

Watch this 2-minute video, “It’s Time to Bail Out the Planet” [Streaming Video], that describes the encroachment of human activity into the natural world as a cause of the COVID-19 pandemic (figure 2.28). As you do, consider: What does the narrator call us to do to prevent pandemics?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0guuB34MKM&t=20s

The producers of the video in figure 2.28 suggest that COVID-19 is not a random event. It is a symptom of a global economic system that is destroying the living planet and destroying wildlife. Through the lens of sociology, we can view our environmental challenges in relation to public opinion, values, behavior, carrying capacity, and inequality. As prompted by COVID-19, we can also see how environmental issues are related to humanity’s relationship with the planet.

Civil Society and Environmental Movements

Social movements are proving very important in addressing environmental challenges due to climate change and biodiversity loss. In addition to global efforts by large organizations like the United Nations, much has been accomplished by smaller organizations around the world. Environmental movements have emerged as one of the most successful forms of sociopolitical mobilization to influence how as humans we respond to environmental changes (Anderson 2016).

Crucial to this, and to all movements, is civil society, the communities, groups, and organizations that function outside of government to support and advocate for certain people or societal issues. They include non-governmental labor unions, Indigenous groups, charitable organizations, faith-based organizations, professional associations, and foundations.

Civil society often serves society by “filling in the gaps” where government and the private sector do not serve the needs of communities. Members working in civil society might advocate for policies at the governmental or in the private sector and hold institutions like the government accountable. Because civil society is distinct from government and business, it is an “intermediary institution.” They might be professional associations, religious groups, labor unions, or citizen advocacy organizations that give voice to various sectors of society and enrich public participation.

One powerful civil society organization is the Sunrise Movement [Website] (figure 2.29). Their website states that they are:

…building a movement of young people across race and class to stop the climate crisis and win a Green New Deal. We will force the government to end the reign of fossil fuel elites, invest in Black, brown and working class communities, and create millions of good union jobs. We’re on a mission to put everyday people back in charge and build a world that works for all of us, now and for generations to come (“We Are the Climate Revolution.” n.d.).

The Sunrise Movement’s efforts have significantly impacted policy in recent years. In 2020, they forced Democrats running for president to outline their plans for cutting U.S. fossil fuel emissions. They have also moved forward with the Green New Deal, a set of policies to address climate change.

Climate change and the ecological crises we face have prompted sociologists to include the environment in their questions, conversations, and research. We know that our environmental challenges are human-made; they impact people, and solutions require changes to multiple social institutions. The worldview that we introduced in the Chapter Story can be described as an environmental social movement. It is one of many initiatives, built by determined people, that are introducing ways for society to shift and address the environmental challenges we face. In Chapter 10, we’ll introduce other grassroots initiatives as we discuss environmental social movements in more depth. Also in Chapter 10, we’ll explore how sociology can help us track and address environmentally related social inequities based on social class, race, and ethnicity.

Going Deeper: Environmental Focus

Sociology instructor Ben Cushing has created a series of podcasts called Tracing the Roots of the Climate Crisis (figure 2.30). Within each recording, Ben applies some ideas we introduce in this text to the social roots of the environmental challenges we face. The podcasts can help you make connections between the intersecting themes we introduce in this textbook.In this first, 11-minute podcast, “Chapter 1: Systems,” Ben makes connections between social systems we introduced in this chapter and the roots of our climate crisis. He asks, “How do certain systems produce certain outcomes for people and the land?”

Licenses and Attributions for Society and the Natural Environment

Open Content, Original

“Society and the Natural Environment” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The first paragraph of “Society and the Natural Environment,” the section “Environmental Sociology,” and content in “Global Climate Change and Disasters” are adapted from 20.3, The Environment and Society, in Sociology by University of Minnesota, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Summary of content created. Added: National Aeronautics and Space Administration content, images of solar cookers and wind turbine “jackets.”

“Environmental Health” and the first three paragraphs of “Emerging Diseases” are adapted from sections in “6.2 Environmental Health” in Introduction to Environmental Sciences and Sustainability by Emily P. Harris, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.25. “Women test a solar cooker in India – 2009” is provided by UN Photo and published on Flickr under CC BY-NC 2.0 (left). “Nigg Energy Park with wind turbine ‘jackets’” is provided by Glen Wallace and published on Flickr under CC BY-SA 2.0 (right).

Figure 2.26. “Aerial view of oil being burned from the BP Deepwater Horizon incident in the Gulf of Mexico, May 2010” (left) and “An oiled gannet is cleaned at the Theodore Oiled Wildlife Rehabilitation Center” (right) are both provided by Deepwater Horizon Response, published on Flickr under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 2.27. “Typical Environmental Health Issues: Determinants and Health Consequences” is replicated from “Introduction to Environmental Sciences and Sustainability” by Emily P. Harris and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.29. “Chicago Sunrise Movement Rallies for a Green New Deal Chicago Illinois 2-27-19” on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain.

Figure 2.30. Tracing the Roots of the Climate Crisis. “Chapter 1: Systems” [Podcast] is produced by Ben Cushing, published by Podbean, and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 2.23. Screenshot from video, “Stockholm, 1972 – When Environmental Protection Was Born” by the UN Environment Programme is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 2.24. Screenshot of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) page on global sea levels is included under fair use.

Figure 2.28. “It’s Time to Bail Out the Planet” by openDemocracy is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

the set of people who share similar social circumstances based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

the study of the interaction between human behavior and the natural and physical environment.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

the communities, groups, and organizations that function outside of government to provide support and advocacy for certain people or issues in society.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.