3.2 Chapter Story

COLOMBIA: LAND, CONFLICT, AND INEQUALITY

In 2016 the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army (FARC-EP) signed a peace agreement that marked an official end to the oldest ongoing armed conflict in the Americas. The 50-year civil war generated the world’s second-largest population of internally displaced persons (people forced to leave their homes but who remain within their country’s borders). More than 220,000 died, most of them civilians. It’s hard to imagine how a country could sustain such a lengthy conflict. But looking closely, the story of Colombia’s civil war points to profound inequality as playing a major role. A central theme of that inequality is related to how land is unequally distributed.

Conflict in Colombia: A Brief History

Resting at the gateway north to Central America, Colombia boasts the second-highest biodiversity in the world, with 35 percent of its territory in the Amazon region (figure 3.1). Despite and in great part due to this richness, Colombia has long been wracked with division and violence.

During Colombia’s colonial period, the king of Spain assigned immense plots of land to the colonists. They forced Indigenous People and later Africans to work in mines, ranches, and agricultural projects that sent goods back to Spain. This social structure created a society based on widespread subordination and exploitation. Spaniards and their descendants in urban areas received economic and political advantages (Bossio 2018). The country’s economic and political society became a hierarchy based on racial distinctions.

This structure continued until 1928, when social inequalities came to a head. More than 1,000 banana plantation workers and their family members were massacred by the Colombian military while striking (White 2002). The workers, protesting the United Fruit Company (UFC, now Chiquita), were demanding better working conditions and payment in real dollars instead of credit from company stores.

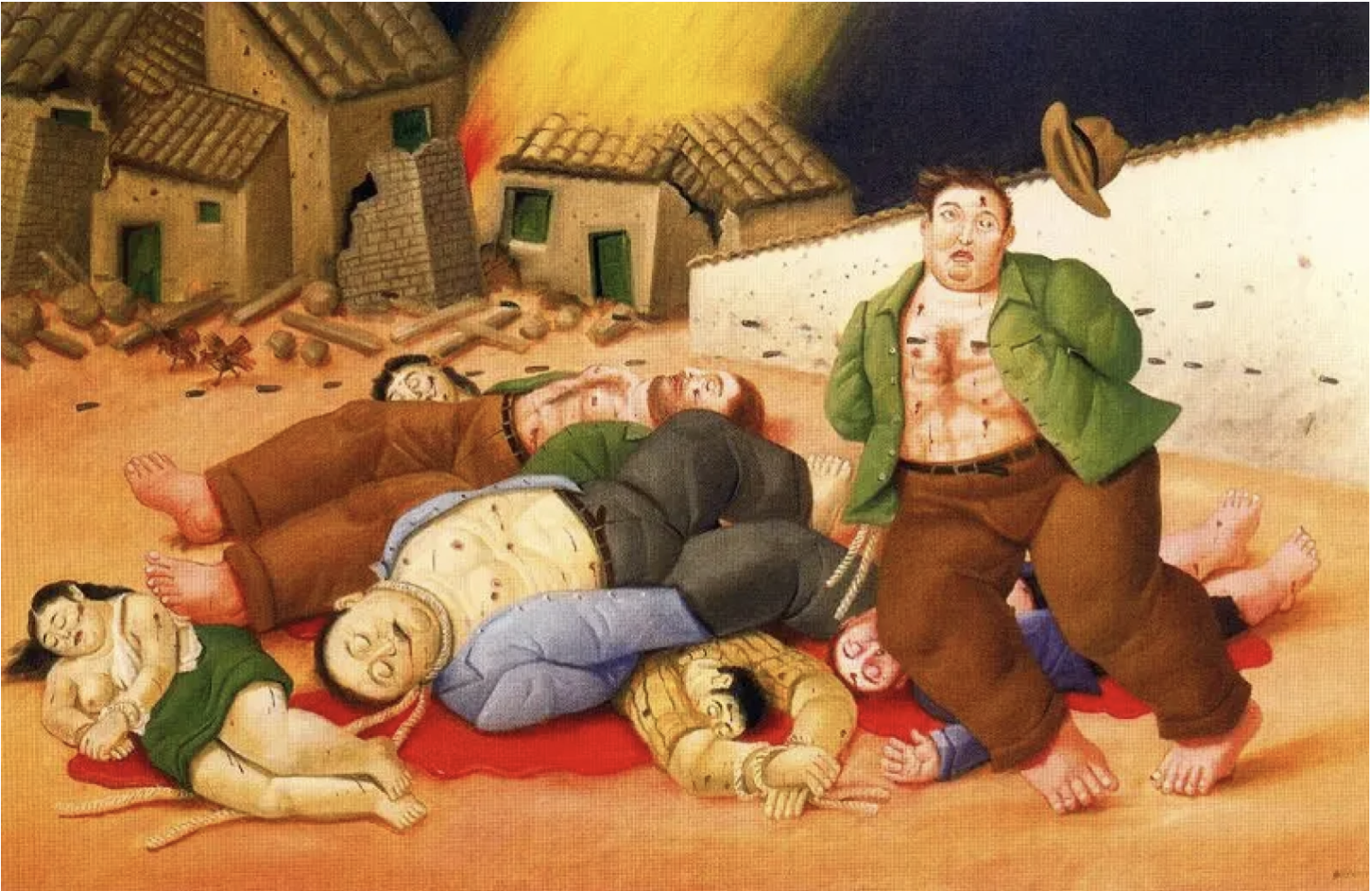

The UFC used its influence to pressure the Colombian government to suppress the strike. After weeks of unrest, workers gathered in the town square of Ciénaga, expecting to talk with company owners. Instead, the Colombian military was called in. They issued a five-minute warning for people to evacuate, by some accounts, closed off access streets (Carrigan 1993), and then opened fire into the dense crowd (figure 3.2). Later, it was revealed that the U.S. government played a role in events that day. The United States threatened to invade if Colombia’s government did not restore order, which was a strategy to protect its economic, political, and military interests in the region (Ramirez Cabal 2023).

The massacre contributed to divisions in Colombia that would ultimately lead to a decade of extreme political violence referred to as “La Violencia.” La Violencia was sparked by the assassination of presidential candidate Eliécer Gaitán in 1948. He was campaigning for political, social, and economic equality, including land reforms to diminish the concentration of land ownership among the elite (Sharpless 1978). These priorities were considerably controversial among the rich in Colombia, and many believed his death was organized by his opponents.

During the 1960s, poor farmers organized uprisings to call for many of the changes Gaitán promised. Armed insurgent groups emerged, hoping to establish more influence. In 1964, the FARC-EP formed a revolutionary armed movement. They organized to fight against the staggering levels of inequality in Colombia; for the rights of the poor, especially in the countryside, and for protection from state-sponsored violence aimed at driving them off their land. They promoted education and healthcare and fought against multinational corporations’ monopolization of Colombia’s natural resources. They became the conflict’s largest rebel group (and later, at some points, controlled 40 percent of the Colombian territory).

In response, the Colombian government authorized the arming of civilians to fight FARC-EP and other guerrillas. This provided more opportunity for paramilitary groups that had been originally organized to provide protection for wealthy landowners and business leaders. The FARC-EP (and other guerrilla groups), the Colombian military, and paramilitary groups fought for control over rural territory.

Residents suffered violence from all armed actors (figure 3.3). With a strong presence in the countryside, the FARC-EP wielded significant and often violent control over communities. In some regions, they deposited land mines. They often issued fees, or a “war tax,” on all commercial enterprises within their controlled territories.

Observers and researchers attribute the majority of human rights violations, such as executions, disappearances, and torture, to paramilitary groups. They often conducted these acts in conjunction with Colombia’s police and military. The police would either participate in paramilitary abuses and massacres directly or deliberately fail to take action (Rochlin 2011).

Social Class and Land Inequality

Since the 2016 signing of the peace agreement, the peace process has continued to move forward. Soldiers have been returning to civilian life, and opportunities are expanding for civilians who previously struggled to survive during the war. However, despite efforts at reconciliation between groups and programs to integrate former armed actors into civilian life, conflict in Colombia continues. Some communities report that they’ve experienced more violence or coercion since the peace agreement was signed (Tackling Colombia’s Next Generation in Arms, 2022). Since 2016, members of the Peace Community of José de Apartadó, introduced in Chapter 1, reported an increase in paramilitary activity in their area. They continue to be targeted, threatened, and killed.

Why do peace and safety remain so elusive in Colombia? Some guerrilla groups have yet to establish peace agreements with the government and remain active. Political leadership didn’t fulfill all the agreements made in the peace accords, leading some FARC-EP fighters to decide not to demobilize. Also, the protections promised by the government have proven to be unreliable.

But more significantly, demobilizing can mean loss of vocation. The most likely reason members join paramilitary groups is that they simply want a job to survive, and the paramilitaries pay better than other groups. Similarly, the FARC-EP recruited or sometimes forced members from poor rural families to join. They often recruited youth with little life experience outside of the war. For members of both groups, giving up their means of income is precarious. The government has targeted both FARC-EP and paramilitaries to receive funds for creating income-generating projects. However, there are delays in the process (United Nations Refugee Agency 2005).

Watch the 7:27 minute video, “A Deadly Peace in Colombia as FARC Disarms” [Streaming Video] (figure 3.4) for a better understanding from FARC-EP members themselves about what demobilization has been like for them. As you listen, apply your sociological imagination to consider: What influenced these former FARC-EP combatants to spend years fighting against the state of Colombia? Why are the men and women in the video concerned about returning to civilian life?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lp4GN_zneIE

There are clear connections between inequality and conflict around the world (Bahgat et al. 2017). In Colombia’s case, severe inequalities contributed to the civil war. The most obvious inequality is related to social class, the set of people who share similar social circumstances based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation. Social class divisions in Colombia are particularly about land ownership. As political scientist Charles D. Brockett exclaims, “The most explosive situations arise when peasants believe that they have been ‘unjustly’ dispossessed of land” (Brockett 1992 as cited in Gillin 2015).

During the war, the theft of land and extreme violence displaced many rural Colombians. According to Oxfam, as a whole, small landholders eventually lost up to 8 million hectares, leaving 80 percent of the land in the hands of just 14 percent of Colombians (Oxfam 2013). Much of the land theft that has occurred in the country is connected to landowners and multinationals seeking to acquire and/or expand their landholdings.

Today, most Colombians live politically and economically marginalized, especially in rural areas (Bossio 2018). It is this unequal land distribution that shapes rural poverty and extreme class inequality. And it is this inequality that, in large part, perpetuates violence in Colombia today, despite the massive efforts toward peace.

In this chapter, we’ll examine how the social construction of identity and our social place, (also defined as social locations), contribute to inequality, inequity, and the lived consequences that result. Colombia’s story focused on divisions and consequences related to social class, but the lived impacts of social inequality across race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation can be equally severe. We’ll also look at how social location and power contribute to systems of oppression. This chapter will encourage you to ask questions about ways that our interactions create inequity and the consequences of that inequity.

- How do our lived experiences differ based on our race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, social class, and colonized history?

- How do multiple social characteristics intersect to produce privilege?

- How do multiple social characteristics intersect to produce disadvantage?

Going Deeper

To learn more about the role of land in Colombia’s conflict, read the illustrated booklet “What’s Land Got to Do With It?” [Website].

Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Story

Open Content, Original

“Chapter Story” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 3.1. “United States of Colombia” by Milenioscuro is licensed under CC BY SA 3.0 (left). “The mountainside in Cocora, Salento, Quindío, Colombia” by Robin Noguiers is licensed under Unsplash License (right).

Figure 3.3. “Small-plot farmers in Antioquia, Colombia” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.2. Masacre en Colombia by Fernando Botero is included under fair use.

Figure 3.4. “A Deadly Peace in Colombia as FARC Disarms” by The New York Times is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

a form of collective action when workers in a given workplace refuse to work until owners meet their demands.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

the capacity to actively and independently choose and to affect change

the set of people who share similar social circumstances based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.