4.5 The Classification of Countries

Social scientists have devised a number of ways to categorize countries based on the sets of economic measures we’ve discussed here. These classification methods can be important in understanding economic differences among countries and identify trends in other areas. However, it’s important to look critically at the ideology that supports those categorizations.

A major concern when discussing global classifications is how to avoid an ethnocentric bias as we describe economic differences among countries. The language that social scientists have used in the past to classify countries originated from the perspective of colonizing countries. Over time, these terms have shifted to make way for more inclusive language. The following sections will describe these changes in more detail.

First, Second, and Third Worlds

The “First World,” “Second World,” and “Third World” framework is one of the first typologies for the classification of countries. It came into use after World War II to distinguish between capitalist democracies, communist countries belonging to the Soviet Union, and all the remaining countries. This classification was primarily a political one, rather than a way to identify countries based on economic stratification.

Eventually, the First and Third Worlds became related to economic development and standards of living. Capitalistic democracies such as the United States and Japan were considered part of the First World. The Third World included most of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The Second World was the in-between category: countries not as limited in development as the Third World, but not as well off as the First World, and having moderate economies and standards of living, such as China or Cuba.

Although still used by many people, First, Second, and Third World terminology has fallen out of favor because it connotes a sense of superiority and inferiority. It also fails to acknowledge the role that colonization has played in determining economic and social inequality between countries.

Watch this 2.5-minute Al Jazeera video, “How The Term ‘Third World’ Is an Outdated Term” [Streaming Video], for a good explanation of the issues with the term “Third World” (figure 4.6).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPTNlB1_WCQ

Later, sociologist Manuel Castells (1998) added the term “Fourth World” to refer to stigmatized minority groups that were denied a political voice all over the globe. These groups include Indigenous minority populations, prisoners, and unhoused populations.

Developed, Developing, and Undeveloped Countries

Another popular categorization applies the concept of development to countries. “Developed” and other derivatives are used, such as “developing” and “undeveloped.” More-developed countries have higher wealth, such as Canada, Japan, and Australia. Less-developed countries have less wealth to distribute among populations, including many countries in central Africa, South America, and some island countries.

These terms emerged during the 1950s and 60s, alongside the notion that richer nations have a responsibility to provide foreign aid to “lesser-developed” countries, thereby raising their standard of living. Although this typology was initially popular and is still widely used, calling countries “developed” denotes a label of superiority in comparison to developed countries. The terms assume that members of less-developed countries want to be like those who’ve attained post-industrial global power. They also imply that unindustrialized countries must improve to participate successfully in the global economy, when in many cases this arrangement provides more benefit for the richer countries.

Wealthy, Middle-Income, and Low-Income Countries

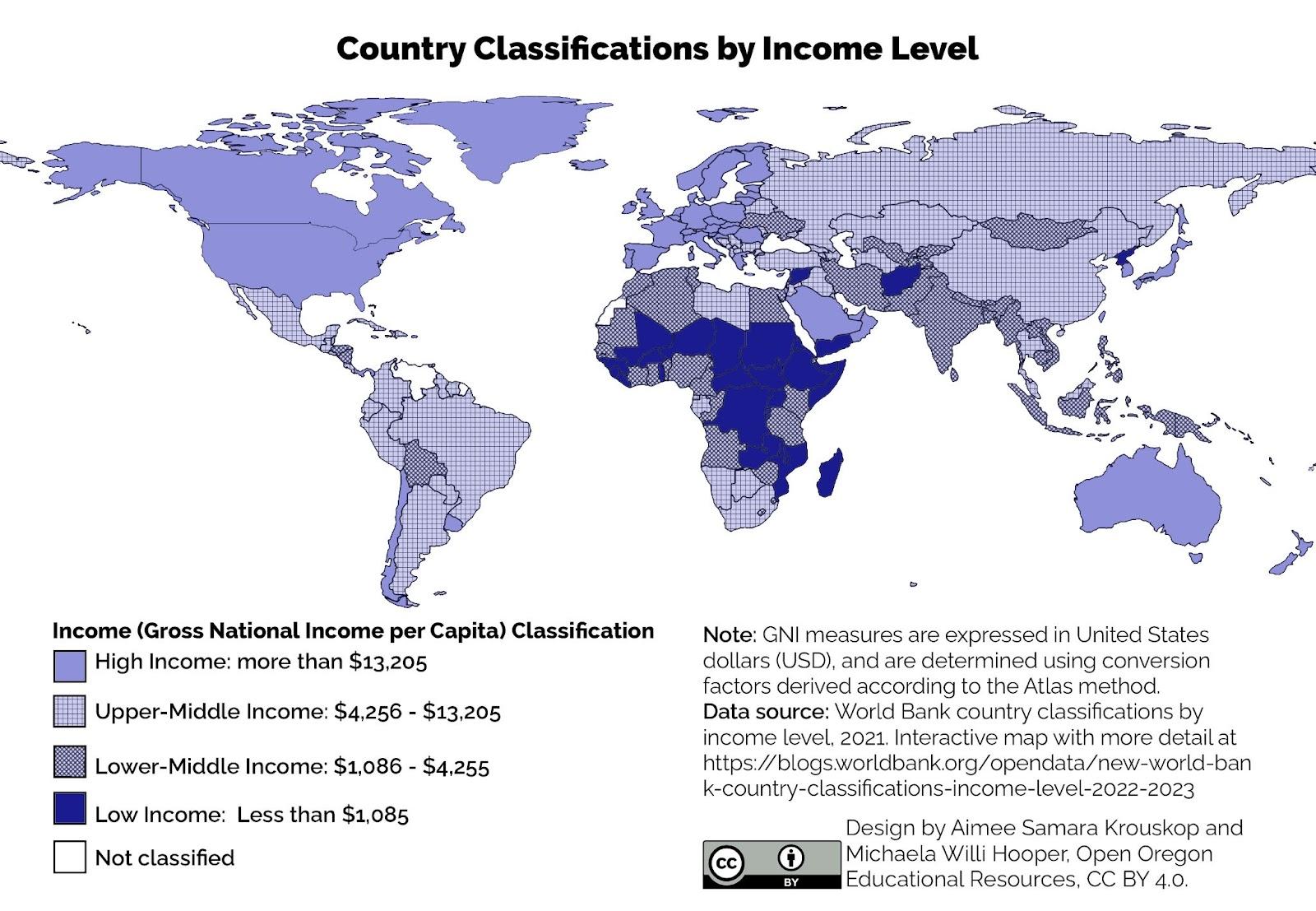

Today, a popular typology simply ranks countries into groups called wealthy (or high-income) countries, middle-income countries, and poor (or low-income) countries, based on measures such as GDP per capita. This typology has the advantage of emphasizing what many researchers consider the most important variable in global stratification: how much wealth a nation has. The other important differences among the world’s countries are considered to stem from their degree of wealth or poverty. Figure 4.7 depicts these categories of countries for 2021 (with the middle category divided into upper-middle and lower-middle levels).

Categorizations based on GDP per capita or similar economic measures are very useful, but they also have a significant limitation. Countries can rank similarly on GDP per capita (or another economic measure) but still differ in other respects. One nation might have lower infant mortality, another might have higher life expectancy, and a third might have better sanitation. Recognizing this limitation, organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) use typologies based on a broader range of measures than GDP per capita.

While the World Bank is often criticized for its policies, it is still a common source for global economic data. Along with tracking the economy, the World Bank tracks demographics and environmental health to provide a complete picture of whether a nation is high income, middle income, or low income. We’ll include World Bank data here to illustrate differences between countries with this typology.

The wealthy or high-income countries are the most industrialized countries. They consist primarily of the countries of North America and Western Europe; Australia, Japan, and New Zealand; and certain other countries in the Middle East and Asia. They are the leading countries in industry, high finance, and information technology, and they exercise political, economic, and cultural influence across the planet. As the global economic crisis that began in 2007 illustrates, when the economies of just a few wealthy countries suffer, the economies of many other countries in the world can suffer too.

Members of wealthy countries live a much more comfortable existence than those in middle-income and poor countries. People in wealthy countries are healthier and more educated, and they enjoy longer lives. Many of these countries were the first to become industrialized, starting in the 19th century, which contributed to the great wealth they enjoy today. It is also true that many Western European countries were wealthy before they industrialized. This is because, as colonial powers, they acquired wealth from the resources of the lands they colonized.

Although wealthy countries constitute only about one-sixth of the world’s population, they hold about four-fifths of the world’s entire wealth. At the same time, wealthy countries use up more than their fair share of the world’s natural resources, and their high level of industrialization causes them to pollute and otherwise contribute to climate change to a far greater degree than is true of countries in the other two categories.

Middle-income countries are generally less industrialized than wealthy countries but more industrialized than poor countries. They consist primarily of countries in Central and South America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Africa and Asia. They constitute about one-third of the world’s population. Many of these countries have abundant natural resources, but still have high levels of poverty, partly because political and economic leaders sell the resources to business owners of wealthy countries and keep much of the income from these sales for themselves.

There is much variation in income and wealth within the middle-income category, even within the same continent. In South America, for example, the GNI per capita in Chile in 2022 was $24,431, compared to only $7,987 in Bolivia (UNDP 2024). Not surprisingly, many more people in the latter countries live in dire economic circumstances in Bolivia than in Chile.

Poor or low-income countries are the least industrialized and most agricultural of all the world’s countries. They are primarily found in Asia and Africa (Hamadeh et al. 2023), where most of the world’s population lives. For example, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and Yemen are considered low-income countries. Many of these countries rely heavily on one or two crops, making them vulnerable to fluctuations in weather and global economic conditions.

By any standard, the majority of people in poor countries live a desperate existence in very challenging physical conditions. Many suffer from deadly diseases; live on the edge of starvation; and lack indoor plumbing, electricity, and other modern conveniences that most people in the United States take for granted. Women are disproportionately affected by poverty, and much of the population lives in absolute poverty, where household income is so low that it is impossible for individuals or families to meet basic needs of life.

Countries’ classifications often change as their economies evolve and, sometimes, as their political positions change. Nepal, Indonesia, and Romania all moved up to a higher status based on improved economies. Sudan, Algeria, and Sri Lanka moved down a level. A few years ago, Myanmar was a low-income nation, but now it has moved into the middle-income category. With Myanmar’s 2021 coup, the massive citizen response, and the military’s killing of protesters, its economy may go through a downturn again, returning it to the low-income nation status (figure 4.8).

Licenses and Attributions for The Classifications of Countries

Open Content, Original

“The Classifications of Countries” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.7. “Country Classifications by Income Level” by Aimee Samara Krouskop and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data from New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2022–2023.

Figure 4.8. Where Is a Place for Me to Sleep in Peace? on Flickr by Ars Electronica is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“First, Second, and Third Worlds” and “Developed, Developing, and Undeveloped Countries” are adapted from “10.1. Global Stratification and Classification” in Chapter 10 Global Inequality by William Little and Ron McGivern in Introduction to Sociology, 1st Canadian Edition, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include additions of video, “How The Term ‘Third World’ Is an Outdated Term (figure 4.6).

“Wealthy, Middle-Income, and Poor Countries” is a remix of sections from “Classifying Global Stratification,” “Chapter 9.1: The Nature and Extent of Global Stratification,” in Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, and Introduction to Sociology: First Canadian Edition Chapter 10 Global Inequality, published by BC Campus with CC Attribution 4.0 International license, found here. Global stratification map (figure 4.7) and image of Where Is a Place for Me to Sleep in Peace? (figure 4.8) added.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 4.6. “How The Term ‘Third World’ Is An Outdated Term” by Maximum Impact with Jay Cameron is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

figures, extents, or amounts of phenomena that we are investigating.

an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

the unequal distribution of economic and social resources among the world's countries.

a statistical estimate based on averages, of the number of years a person can expect to live in a certain region.

a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.