4.6 Theories of Inequality Between Countries

The study of global stratification that focuses on inequality between countries compares the overall wealth, status, power, and economic stability across countries in the world. That study also focuses on change across time and the social forces that influence those changes.

For example, a classical sociological view observes that in the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution created an unprecedented jump in wealth for Western Europe and North America. Due to mechanical inventions and new means of production, people moved from farming and artisan work to employment in factories. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, industrial technology had raised the economic standard for many in those countries.

The Industrial Revolution also saw the rise of vast inequalities between countries that were industrialized and those that were not. As some countries embraced technology and saw increased goods and wealth, the non-industrialized countries fell behind economically, and the gap widened.

The Industrial Revolution perspective is one way of describing economic inequality at the global level. This section will explore some broader perspectives that attempt to make sense of why global stratification exists: modernization theory, dependency theory, and world systems analysis.

Modernization Theory

The Industrial Revolution perspective was a focus of the theory of modernization, an early framework that was introduced by German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920). Sociologist Talcott Parsons (1902–1979) developed later ideas that added to the perspective. According to modernization theory, low-income countries are affected by their lack of industrialization. They can improve their global economic standing through:

- an adjustment of cultural values and attitudes around work

- industrialization and other forms of economic growth (Armer and Katsillis 2010)

The perspective posits that with assistance, “traditional” countries can be brought to development in the same manner more developed countries have been.

Proponents of modernization theory claim that as countries modernize, they become wealthier and more powerful and their citizens enjoy a higher standard of living. For example, mobile broadband access can improve rates of education, and improved roads can accelerate the speed to which companies can deliver their products. Proponents point to data showing that modernized countries tend to have lower maternal and child mortality rates, longer lifespans, and less poverty, while in the poorest countries, millions of people die from the lack of clean drinking water and sanitation facilities.

Critics claim that modernization theory has an ethnocentric bias. That is, its followers view their own society and culture as superior, then determine standards based on that judgment. It supposes all countries have the same resources and are capable of following the same path. In addition, it assumes that the goal of all countries is to be as “developed” as possible. There is no room within this theory for the possibility that industrialization and technology are not the best goals. At the same time, the issue is more complex than the data on higher standards of living might suggest. Cultural equality, community, and local traditions are all at risk as modernization encroaches.

Dependency Theory

Scholars have criticized modernization theory since the 1970s. As a result, political theorists and sociologists have begun to explain global inequality in terms of power imbalances between countries. Dependency theory developed as a response to modernization theory as social change theorists began to investigate problems arising from development practices.

Dependency theory views global inequality as primarily caused by high-income countries exploiting middle-income and low-income countries. This creates a cycle of dependence (Hendricks 2010). Proponents of this theory point out that as long as low-income countries are dependent on high-income countries for economic stimulus and access to a larger piece of the global economy, they will never achieve stable and consistent economic growth.

Dependency theory argues that the concentration of resources held by certain countries significantly affects the opportunities of individuals in poorer and less powerful countries (Little et al. 2014). One direct example can be seen in how members of richer countries, through government or corporations, will acquire land in poor countries. Often, corporations from rich countries purchase land for production, or governments of rich countries purchase land to meet their food and energy requirements at home (Rulli et al. 2013:1). This primarily occurs in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Some of these deals are considered land grabs. According to the International Land Coalition, land grabs are “land acquisitions that are in violation of human rights, without prior consent of the preexisting land users, and with no consideration of the social and environmental impacts” (International Land Coalition 2011).

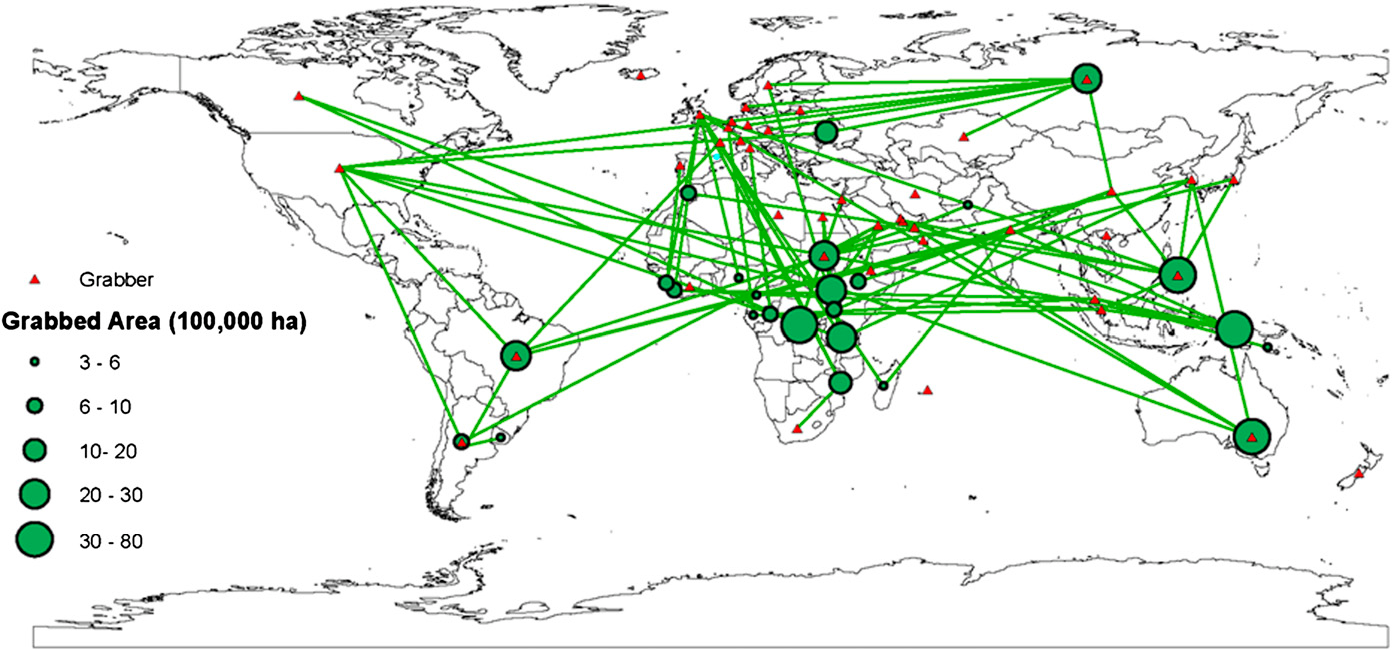

Often, land is taken away from local smallholders, especially in areas of the world where people have lived on the land for generations, maintaining community agreements about how they will use and share it. Property from land grabs tends to be used for large endeavors such as monocropping or generating hydropower. Land grabbers will gain control of areas in several ways. They might lease the land from governments, arranging for the farmers who reside on the land to sharecrop. Or they might actually purchase the land, forcing people into contracts that require them to use the land in a way that benefits the land grabber. Figure 4.9 shows a global land grabbing system documented in 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2NCNr2Brw8

It is difficult to track how extensive the issue of land grabbing is. As a global society, we have not yet determined a common definition or a good way of monitoring the practice. Also, many transactions are conducted in secrecy. However, author Fred Pearce estimates that land exceeding the size of Western Europe was grabbed from poor countries by rich countries’ corporations between 2000 and 2011 alone. In 2010, the World Bank estimated that 150 million acres of land were grabbed, and the humanitarian aid agency Oxfam estimated 560 million for the same time frame (Pearce 2021).

Watch the 2:20-minute video “Land Grabbing in Mali” [Streaming Video] for a good illustration of land grabs (figure 4.10). As you watch, pay attention to how land grabbing impacts Malian farmers, ranchers, and their families.

World Systems Analysis

Another way to look at power dynamics and global dependency is as a layered system. Sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein (1930–2019) introduced the world systems analysis framework. It describes the global economy as a complex system that supports an economic hierarchy. In other words, some countries are in positions of power with numerous resources, and others exist in a state of economic subordination. Those countries with less power face significant obstacles to competing in the economic hierarchy. World systems analysis places the world’s countries into three categories: core countries, peripheral countries, and semi-peripheral countries.

Core countries are dominant capitalist countries. They are highly industrialized, technological, and urbanized. For example, the United States is a core nation, an economic powerhouse that can support or deny support to economic legislation with far-reaching implications. As a result, the United States can exert control over every aspect of the global economy and exploit less powerful countries. Free trade agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which in 1994 established a free trade zone for Mexico, Canada, and the United States, demonstrate how core countries utilize their power to secure the most advantageous position in global trade.

Peripheral countries such as Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, and Nepal have very little industrialization. What peripheral countries do have often represents the outdated castoffs of core countries or the factories and means of production owned by core countries. They are economically dependent on core countries for jobs and aid.

Semi-peripheral countries are in-between countries. They are not powerful enough to dictate policy, but nevertheless act as a major source of raw material and an expanding middle-class marketplace for core countries. Semi-peripheral countries also exploit peripheral countries. Mexico is an example of this. Mexico provides abundant cheap agricultural labor to the United States and supplies goods to the U.S. market. The United States dictates the market rate of goods, and Mexican workers go without the constitutional protections offered to U.S. workers.

Dependency theory and world systems analysis have been criticized for having an incomplete description of the socioeconomic conditions of poorer countries. Some thinkers argue that it makes too many broad generalizations without sufficient quantitative study to support the ideas. Others say that it wrongly assumes globalization and capitalism affect all regions.

Comparing Globalization Theories

For a summary of the connections between globalization, dependency, and modernization analysis, watch this 4-minute clip from the video, Khan Academy on globalization theories [Streaming Video] (figure 4.11). The video also introduces three globalization perspectives: hyperglobalist, skeptical, and transformationalist. Which perspective makes the most sense to you?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCZB6Xc42F0

Going Deeper

- To learn more about land inequality and land defenders, see the website of the International Land Coalition, the report “Custodians of the Land, Defenders of our Future: A New Era of the Global Land Rush” [PDF], and the report “Land Inequality at the Heart of Unequal Societies” [PDF].

- For more on land grabs, watch this 5:06-minute video, “New Film Exposes the Devastating Impact of World Bank Backing for Land Investments in Uganda,” and this 5:32-minute video, “‘Land-Grab’ for Food Security.”

Licenses and Attributions for Theories of Inequality Between Countries

Open Content, Original

“Theories of Inequality Between Countries” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The introduction paragraphs of “Inequality Between countries” are adapted from “9.3 Global Stratification and Inequality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang in Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Modernization Theory” and “World Systems Analysis” are adapted from Chapter 10: Global Inequality by William Little and Ron McGivern in Introduction to Sociology, 1st Canadian Edition, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The first two paragraphs of “Dependency Theory” are adapted from Chapter 10: Global Inequality by William Little and Ron McGivern in Introduction to Sociology, 1st Canadian Edition, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“World Systems Analysis” includes adapted content from “Global Stratification and Classification” in Rothschild’s Introduction to Sociology by Teal Rothschild, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.11. “Globalization Theories” by Sydney Brown, Khan Academy, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. This version has been clipped at 4:05.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 4.9. “A Global Map of the Land Grabbing Network” by Maria Christina Rulli, Antonio Saviori, and Paolo D’Odorico in their 2013 article “Global Land and Water Grabbing” by Inter Press Service (2021) is included under fair use.

Figure 4.10. “Land Grabbing in Mali” by GreenTV is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the unequal distribution of economic and social resources among the world's countries.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

a complex set of changes that take place in societies that move from traditional to modern practices as their economies become industrialized.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

land acquisitions that are in violation of human rights, without prior consent of the preexisting land users, and with no consideration of the social and environmental impacts.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

aid to alleviate suffering and mitigate the effects of disaster provided by governments and non-governmental organizations for a short-term period until longer-term help can be provided by local governments or other institutions.

the capacity to actively and independently choose and to affect change

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.