5.3 Foundations of Global Inequality

What has led to the patterns of inequality that shape and divide this world? Why are some places and peoples so wealthy and others so poor? There are no simple answers to questions that extensive. However, good answers would probably start with some history.

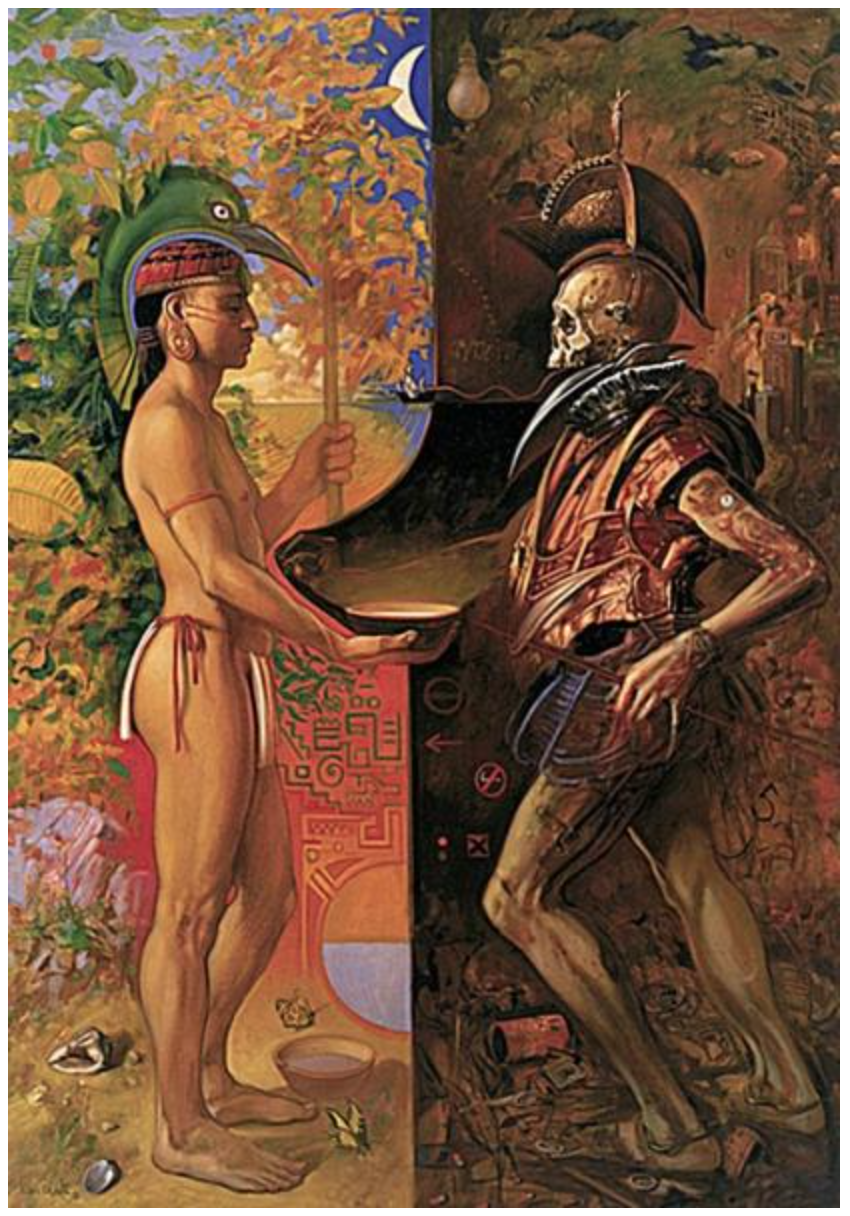

The painting in figure 5.3 titled Encuentro (in English, “Meeting” or “Encounter”) was created by Jaime Zapata in 1992. It represents a meeting between an Indigenous person and a conquistador (an early Spanish colonizer). The Indigenous person is presented as living in good health, with an abundance of nature, offering a bowl to the conquistador. The conquistador is depicted with deathly imagery and examples of a destructive modern civilization. It’s a powerful illustration of the start of a long series of events driven by the colonial system that dramatically shaped the modern world.

This section will introduce the kinds of colonialism and the ideologies of colonialism as they existed during the era of Zapata’s Encuentro. It will also explore how those ideologies and actions of colonialism have transformed into systems of power that exist today.

Colonialism

The modern system of inequality has grown in great part out of the colonial system that governed much of the world over the past several centuries. We introduced colonialism in Chapter 1 as the policy of military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. Colonization is the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the Indigenous people of an area.

European colonialism has reordered the global map, often waging wars of physical and cultural genocide on people, from West Africa to the Pacific Northwest. So if our question is about the roots of contemporary global inequality, our attention should focus a good deal on European colonialism. After all, it is not an accident that the wealthy countries in the world today are also former colonial powers, while most of the poor countries are former colonies.

European colonialism can be divided into two main forms:

- Colonies of rule are colonies governed by a relatively small population of colonial administrators, usually for the purpose of extracting resources and wealth. England’s colonization of India would be considered a colony of rule.

- Colonies of settlement are colonies in which the colonial power sends a large number of its domestic population to settle the colony, thus displacing the Indigenous population. The English colonies in North America offer one important example of this. Colonies of settlement tend to be even more violent than colonies of rule, as they often involve the forced removal or mass murder of Indigenous Peoples.

So how did colonialism create the patterns of wealth and inequality that make up our world today? As a political-economic system, colonialism enabled the colonial powers to extract wealth from colonized societies, often in the form of agricultural products (like cotton, tobacco, or sugar) or mineral resources (like gold, silver, or oil). People were enslaved either from within conquered countries or brought in to serve in the extraction and production of goods. In the Americas, colonists also benefited from the encomienda. Also called the hacienda system, this was a labor system whereby the Spanish Crown rewarded conquerors with the labor of conquered non-Christian peoples.

Colonialism simultaneously enriched the colonial elite and impoverished the colony by extracting wealth from the colony and concentrating it within the colonial power. Thus, it formed an economic relationship that resulted in the enrichment of one party by way of the impoverishment of the other. The wealth of the wealthy and the poverty of the poor are ultimately two sides of the same coin—two sides of a relationship of extraction (McMichael 2017).

To create these relations of economic extraction, colonial powers attacked and restructured the social and economic lives of colonized peoples. To establish new colonial economies, most aspects of Indigenous life had to change. Local agriculture, with all of its cultural significance and nutritional complexity, was often transformed into export-oriented monocrop agriculture. Family and gender systems were often transformed, as European patriarchal traditions limited women’s access to land and other resources (Waylen 1996). And colonial elites oversaw various assaults on Indigenous language, culture, and spirituality.

The U.S. government, in collaboration with the Catholic Church, orchestrated a sustained campaign to destroy Native American cultures and identities. One part of this campaign was the development of residential schools for Native American children. We’ll discuss more about this campaign in Chapter 8 in the context of education. For a piece of this story now, you can find a 13:41-minute video in the Going Deeper section.

Ideologies of Colonialism

European colonialism involved genocide, enslavement, displacement, and impoverishment. But like most systems of power, it was legitimized by a host of ideologies. Ideology refers to the collection of ideas that form a person’s worldview and help them make sense of the society in which they live. Colonial ideologies made colonialism appear legitimate, inevitable, and desirable in the minds of many of the people who carried it out.

The colonial powers almost universally presented their rule as a “civilizing force” that would ultimately benefit colonized people. The civilization mission has been articulated in different ways in different times and places, but it invariably frames colonized people as backward and in need of some “superior” society to intervene to improve their lives. It is a mix of dominance and paternalism—presenting colonization as serving the best interests of colonized people.

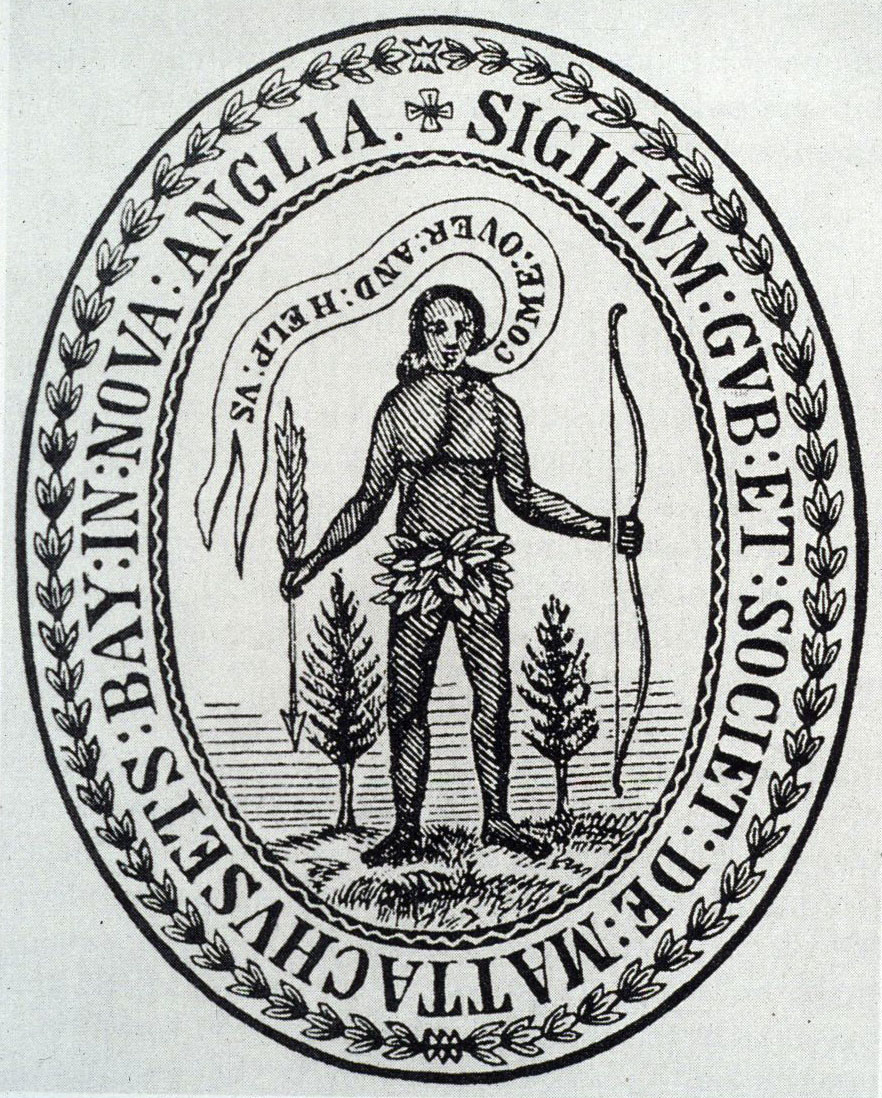

Take, for example, the 1629 Massachusetts Bay Colony seal (figure 5.4). As a symbol of the recently established British colony, it depicts a Native man, naked except for leaves over his groin, with a scroll emerging from his mouth that reads, “Come over and help us.” The image depicts Native people as living in an Edenic state of nature, in need of salvation and civilization.

While the civilization mission has been deployed throughout all periods of European and U.S. colonialism, it has been articulated in different ways. By the late 19th century, it had become highly racialized. The British poet and author Rudyard Kipling coined it “the white man’s burden” in his 1899 poem by that name. It reads in part:

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

The white man’s burden became popular as a framework for interpreting colonial expansion—framing colonized people as simultaneously childlike and dangerous, while framing agents of colonial power as stern and wise parents.

The social theorist Edward Said argued in his classic book Orientalism that European colonialism constructed and rested upon a certain view of the world (Said 1978). That worldview divided “the West” or “the Occident” from “the East” or “the Orient.” In doing so, it separated various cultural groups into these two broad categories, erasing their actual cultural complexities and histories and forging a clear sense of “us” and “them.”

It also assigned each group certain characteristics. The so-called “West” represented the so-called “East” as, among other things, static, sensual, perverse, mystical, and despotic. In doing so, the “West” represented itself as the opposite: progressing, rational, moral, scientific, and liberal. From Said’s perspective, colonialism rested on a discourse of power—a certain way of seeing and organizing the world. He called that discourse “Orientalism.”

For more on the ideologies of colonialism, you can listen to the podcast “The Walls Built in Our Minds,” which was introduced in Chapter 3.

Neocolonialism

When did the colonial period end? That question is more difficult to answer than it might seem.

Throughout the colonial period, colonized peoples organized innumerable campaigns of resistance, from Indigenous uprisings to slave revolts to independence campaigns led by colonial settlers. The first successful expulsion of a colonial power was the Haitian Revolution. In 1791, formerly enslaved people in Haiti rebelled against their French colonial administrators and won formal independence in 1804. However, the majority of colonies around the world did not gain their independence until much later.

World War II (1939–1945) marked the beginning of the end of formal colonialism. In the period just following the war, anti-colonial forces successfully took advantage of the weakened state of the colonial powers. Independence movements spread around the world, and former colonies became independent nation-states. So one could argue that the colonial period ended between the 1940s and 1960s.

However, many scholars suggest that the colonial period hasn’t ended at all, only changed. Neocolonialism is a new form of colonialism in which the colonial powers maintain their economic and political dominance over former colonies through debt, trade agreements, and corporate influence but without formal political control.

Following formal decolonization, many newly independent states found themselves under significant pressure from the wealthy nations, particularly the United States and the Western European powers. That pressure was discussed in 1961 during an All African People’s Conference, an event organized by a movement of political groups from countries in Africa that opposed colonial rule.

There, neocolonialism was described as “the deliberate and continued survival of the colonial system in independent African states, by turning these states into victims of political, mental, economic, social, military and technical forms of domination carried out through indirect and subtle means that did not include direct violence” (Mentan 2018:280). While Africa is not the only continent that is subject to neocolonialism, its states experience a profound and pervasive form of this domination.

An African state that staunchly resisted neocolonialism at this time was Ghana, with leadership coming from Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister and president of the country (figure 5.5). He is a central thinker in our understanding of neocolonialism and was one of the first to coin the term. In his book Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonisation, Nkrumah critiqued that aid, trade, finance, and security interventions would be used as a tool by foreign powers to keep African former colonies economically and politically subordinate to their interests. “The cajolement, the wheedlings, the seductions and the Trojan horses of neocolonialism must be stoutly resisted, for neocolonialism is a latter-day harpy, a monster which entices its victims with sweet music” (Nkrumah 1964:105).

Going Deeper

- For more on the U.S. residential schools, watch the video “How the U.S. Stole Thousands of Native American Children” [Streaming Video] (13:41).

- To learn more about the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, watch this 11:28-minute video, “Why Are the IMF and World Bank So Controversial?” [Streaming Video].

- To watch more on how colonialism affects societies today, watch the 25:18-minute Al Jazeera video “How Does Colonialism Shape the World We Live in?” [Streaming Video]. Also, a 25:26-minute follow-up video is “Colonialism: Have We Inherited the Pain of Our Ancestors?” [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for Foundations of Global Inequality

Open Content, Original

“Roots of Global Inequality” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.3. Encuentro by Jaime Zapata is on Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.4. “Massachusetts Bay Colony Seal (1629)” by unknown author, is on Wikipedia and in the public domain.

Figure 5.5 “Kwame Nkrumah” by Boris Chaliapin, is on Wikipedia and in the public domain (left).

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.5. Mural of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana by Ray Black, PhD, Associate Professor, with the Race, Gender, and Ethnic Studies Department of Colorado State University is included with permission (right).

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

colonies governed by a relatively small population of colonial administrators, usually for the purpose of extracting resources and wealth.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

colonies in which the colonial power sends a large number of its domestic population to settle the colony, thus displacing the Indigenous population.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

a perspective that frames colonized people as backward and in need of some “superior” society to intervene to improve their lives.

a framework for interpreting colonial expansion - framing colonized people as simultaneously childlike and dangerous, while framing agents of colonial power as stern and wise parents.

a newer form of colonialism in which colonial powers maintain their economic and political dominance over former colonies through debt, trade agreements and corporate influence but without formal political control.