5.5 Mixed Impacts of Foreign Assistance, Humanitarian Aid, and Development

The combined efforts of foreign assistance, humanitarian aid, and development since the 1960s is immense. Since the 1970s U.S. assistance has helped cut in half the number of preventable deaths of children under five, people living in poverty, and the number of children and adolescents unable to attend school (Interaction n.d.).

The average lifespan increased by 24 years between 1960 and 2017 (Norris 2021). Extensive campaigns against cholera, smallpox, malaria, and polio have been very successful, with polio nearly eradicated and smallpox abolished entirely. Campaigns have also successfully shifted economic circumstances to allow millions of girls access to a basic education and offered family planning programs that give women and men a chance to choose smaller families.

In 2020, the United States sent about $63 billion in foreign assistance to other countries (a considerable amount, but less than 1 percent of the federal budget). The total global aid (humanitarian and foreign assistance) since 1960 has been about $4.7 trillion, calculated as a combination of cash and in-kind and personnel support and taking inflation into account (Barder 2014).

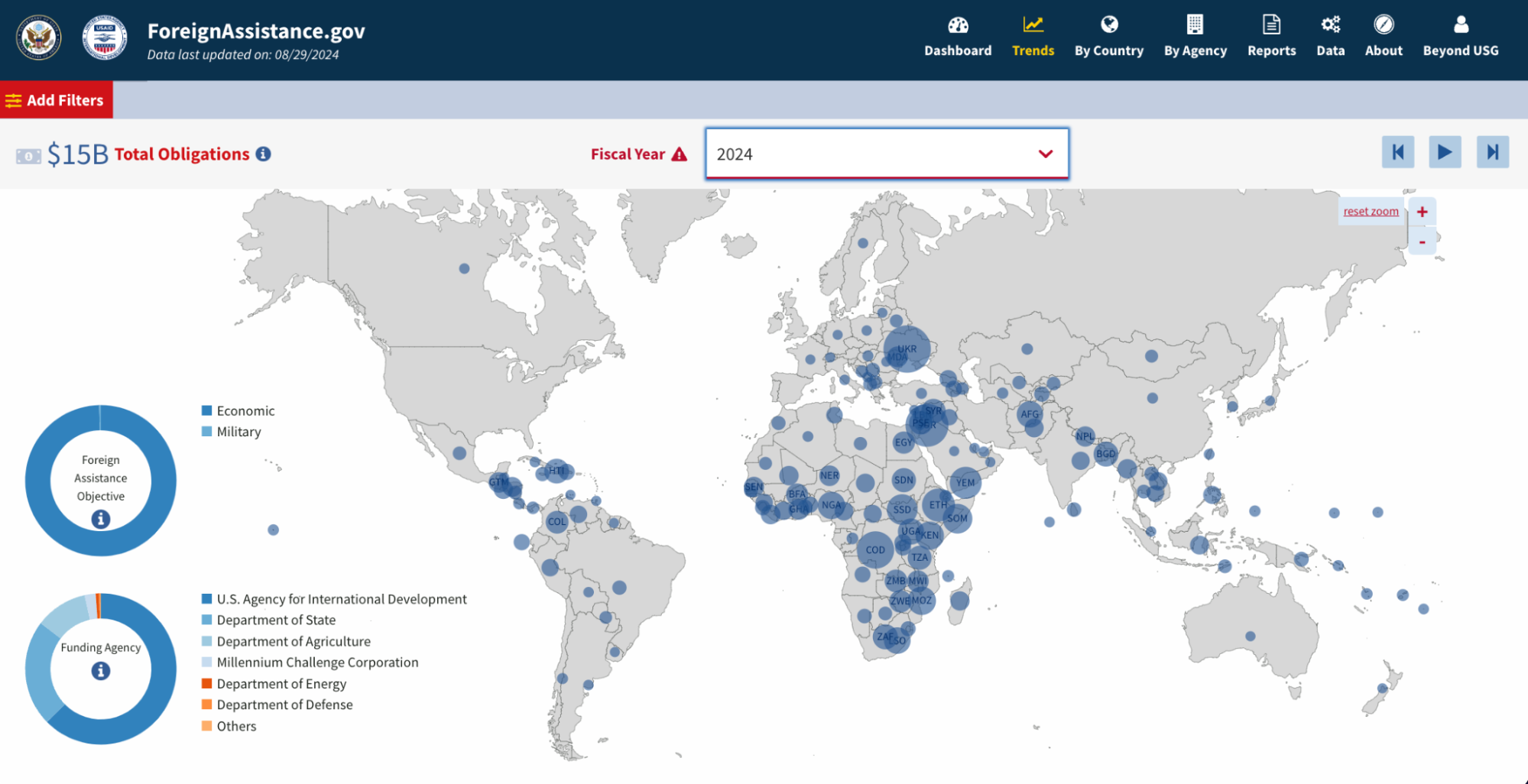

Take a brief look at this interactive map of the USAID [Website] (figure 5.8) that documents trends in U.S. foreign assistance. Set the year to 1946, press play, and watch where dollars were obligated to foreign countries through the decades until today. What overall changes do you notice? What connections can you make between political, historical, and environmental events that might account for the funding priorities for some of those years?

Does Humanitarian Aid Work?

Depending on the circumstances, it can be challenging or straightforward to evaluate how well foreign assistance, humanitarian aid, and development work to achieve their stated goals, especially humanitarian aid. Recipient organizations and governments are often criticized for not demonstrating the effectiveness of the programs for which they receive funding. Some goals, such as sustainable development, are more difficult to show outcomes for. It can also be challenging to show shifts in society’s wellbeing over the short term (Council on Foreign Relations 2023).

There are some circumstances where it is easier to track and report the impacts that aid has created. The Council on Foreign Relations points to a good example:

As of 2020, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has delivered care to more than 17 million people (including 6.7 million children) and provided training for 290,000 health workers in sub-Saharan Africa. When the program launched in 2003, less than 50,000 people in Africa had access to any antiretroviral treatment (Nakkazi 2023) (Council on Foreign Relations 2023).

There are countless projects like PEPFAR that distribute humanitarian assistance and make marked inroads in treating disease, bringing water to homes, or other tangible initiatives. However, even among these direct missions, it is important to consider the challenging circumstances that members of recipient nations face (that is, after all, why they are targeted to receive funds). The image in figure 5.9 from USAID introduces midwives in Ethiopia, trained to track HIV status in mothers and HIV-exposed babies.

USAID shares:

These women may have long distances to travel to the health center and no address or phone number to follow up. Other issues such as staff turnover have a huge effect on quality of care. When health center staff are assigned to remote areas, there is a high chance that they will want to transfer somewhere else at the first opportunity. With turnover comes gaps in training and inconsistency when it comes to tracking and reporting on HIV positive patients (USAID Ethiopia 2013).

It is also important to consider cultural differences between the countries that send funds and those that receive support. Recipients may not be prepared to meet the specific cultural expectations for reporting outcomes that members of donor nations have.

Critical Responses to Foreign Assistance, Humanitarian Aid, and Development

As a global community, what did we learn from 60 decades of foreign assistance and development action? We’ve learned how to respond to conflicts related to war, natural disasters, and famine. We’ve also learned how to measure, monitor, and improve severe levels of poverty, lack of education, and severe global health emergencies such as pandemics. We’ve also developed a rapid and encompassing global emergency response system.

Alongside these developments, in the mid-1990s, we began to see a watershed of scientific and grassroots critique of foreign assistance and development applied by many large-scale organizations. Today, some see that these models are responsible for soaring international and local financial indebtedness, exacerbation of human rights crises, depleted soils, threats to native seeds and biodiversity, erosion of knowledge and skills of local people, and loss of local cultural expression.

National Interests and Support to Foreign Nations

Key to understanding globalization and inequality is the fact that often national funds and the work of government-sponsored organizations are offered with the added purpose of serving the interests of their home nation. These interests might be straightforward. For example, nations might donate to poor countries to reduce possible negative spillovers of issues from poor nations. Avoiding infectious disease, environmental degradation, violence, and human trafficking are some examples.

Other interests may be more complicated. Governments of richer countries also have an interest in opening new trade markets and keeping current ones healthy. If they can donate to struggling nations, helping them avoid crises and become more prosperous, it means there are more people to buy their goods. To some thinkers, in this way, aid can perpetuate neocolonialism through trade agreements and corporate influence.

Other thinkers posit that when funds are vested in struggling countries for the interests of donor nations, more poverty and violence are created. Author John Norris lists some examples of U.S. assistance that have proven to create more problems than help. Support to Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, to Egypt in the 1980s and 1990s, and to Afghanistan and Iraq in the wake of September 11 has yielded disappointing and detrimental results. He adds, “Each of these settings involved high-profile national security priorities, where resources and manpower were almost unlimited but there was very little willingness to question how, or even if, development could work under such conditions” (Norris 2021).

A more current example is with the U.S. food aid program, an initiative of USAID. The program has required that food be supplied to poor nations from U.S. farms and transported on U.S. ships. Some see this arrangement as a “win-win,” as the U.S. farmers receive income for the food they provide. However, with this system, the program feeds far fewer people than it could if food were delivered from a closer region. It is also a considerably ineffective way of delivering aid. In 2018, members of Congress introduced changes to this system that would give the USAID the flexibility to use cash, vouchers, or locally purchased food when one of those would be faster and more effective in helping hungry people in need (Casey 2021).

There’s a long history of controversy surrounding the importation of food to poor nations, particularly when it is driven by powerful corporations. In the 1970s, the Swiss food company Nestlé faced international criticism for its marketing practices. Protesters claimed Nestlé’s promotion of their baby formula was causing infant illness and death in poor communities, as it encouraged mothers to abandon breastfeeding.

Controversy with Nestlé has continued since the 1970s (INFACT Clearinghouse 1978). In 2011, 19 NGOs based in Laos organized a boycott of Nestlé, criticizing the company for failing to translate labeling and health information into local languages and for offering incentives to doctors and nurses to promote the use of infant formula (“Aid Agencies in Laos Refuse to apply for Nestlé Cash” 2011).

Watch this 3:56-minute video produced by The New York Times, “How Junk Food Is Transforming Brazil” [Streaming Video] (figure 5.10), which describes how the Nestlé controversy shows up in Brazil. As you watch, consider that today, Nestlé is the largest publicly held food company in the world. It also provides donations to development organizations such as the World Health Organization Foundation (Igoe 2021) and is collaborating with the Swiss government on development efforts (Frederick 2020). What potential concerns and consequences can you see with powerful food companies working with governmental and international aid agencies?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cKUDIte2sk&feature=emb_imp_woyt

Militarism, Human Rights, and Regime Change

Some international military interventions and international organizations are controversial in the context of human rights, assistance, and development. An organization of the international military system that has come under great scrutiny is the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC).

Formerly called the School of the Americas, WHINSEC is a U.S. Department of Defense school. Since the school’s initial opening as the School of the Americas, the organization has trained over 64,000 Latin American soldiers in counterinsurgency techniques, sniper tactics, commando and psychological warfare, military intelligence, and interrogation tactics (Knapke 2019).

A number of graduates of the School of the Americas and WHINSEC have been accused and sentenced for human rights violations, genocide, crimes against humanity, and other criminal activity in their home countries (School of the Americas Watch 2007). Further criticism is related to training manuals used at the school, provided by the U.S. military, that referenced execution, torture, blackmail, false imprisonment, and other forms of coercion (Priest 1996). Other manual information referred to “potential insurgents” as “religious workers, labor organizers, student groups, and others in sympathy with the cause of the poor” (Quigley 2005), which is a violation of international humanitarian law.

The School of the Americas Watch is an organization dedicated to closing the school and monitoring officers known to have committed atrocities after graduating. They have documented atrocities including the assassination of Catholic bishops, labor leaders, women and children, priests, nuns, and the massacres of entire communities. The School of the Americas Watch has organized protests against WHINSEC that include direct action at the school itself (figure 5.11).

Over recent years, WHINSEC has received just under $10 million (approved by Congress) per year to run the Washington Office on Latin America’s Defense Oversight Program. The training of Latin American soldiers is important to members of the U.S. Department of Defense and some lawmakers because it is seen as critical to U.S. national security. In 2007, former U.S. Representative Phil Gingrey explained:

[The school]…may be the only medium we ever have to engage the future military and political leaders of these Latin American countries, who are America’s closest neighbors.…If we were not to engage with these nations…the void created would be filled by countries with different values than our own regarding democracy and human rights, countries such as Venezuela and China, whose influence in the region is growing (Grills 2011).

Modern U.S. national security interests related to countries with “different values than our own” goes back to the Cold War, the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence between Russia (then the Soviet Union) and the United States. The direct Cold War between the two countries began shortly after World War II. The Soviet Union supported the expansion of communist governments around the globe, and the United States supported anti-communist regimes. This conflict has manifested in the United States supporting a number of coups and other military interventions. In the case of WHINSEC, Panama’s former president Jorge Illueca described the school as the “biggest base for destabilization in Latin America” (Johnson 2004).

Concern about communist influence has waned considerably, but it still influences some U.S. policymakers today. After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, terrorism eclipsed communism as the major threat considered when prioritizing aid.

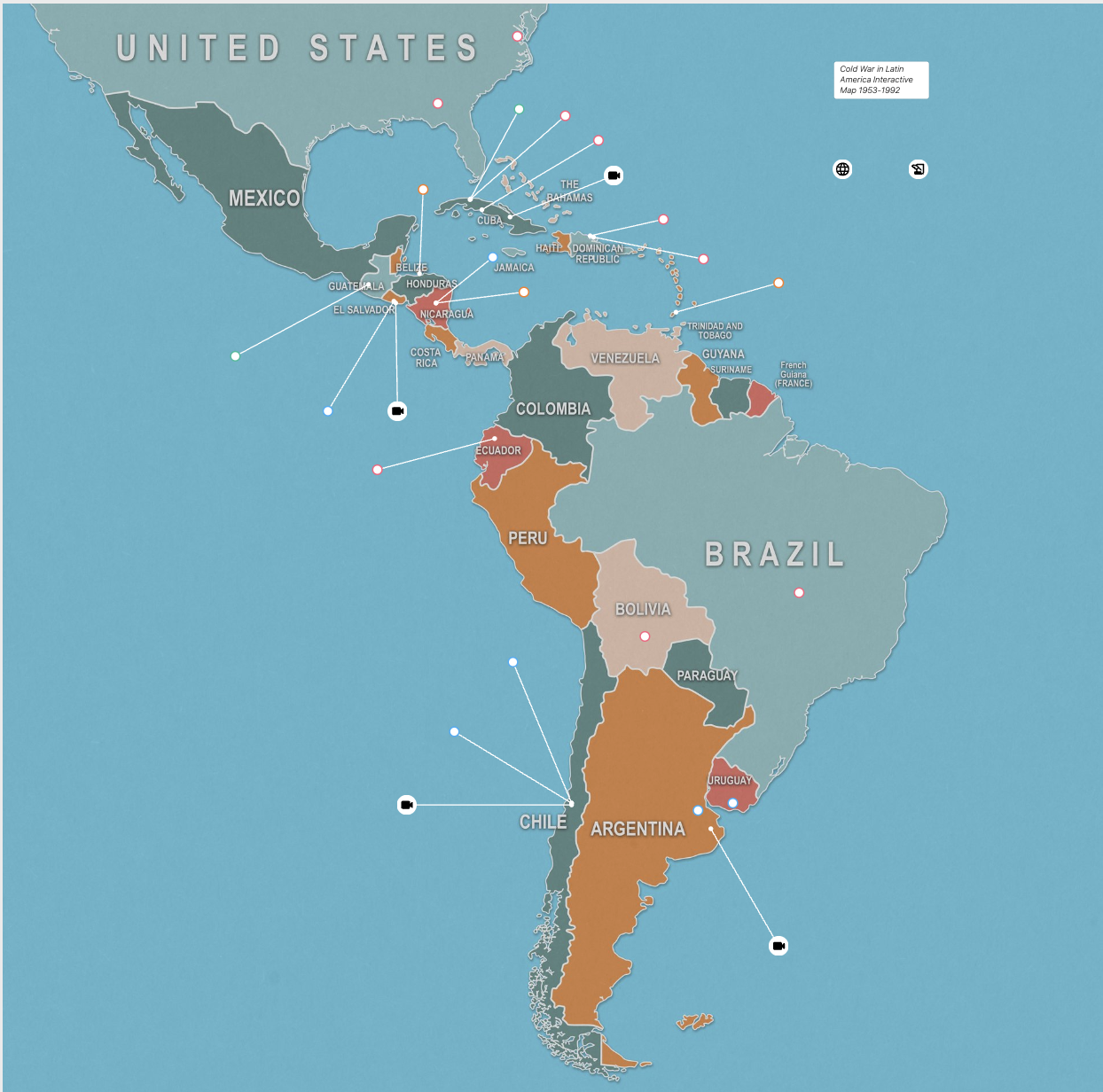

Take a few minutes to browse this Cold War in Latin America Interactive Map [Website], created by David Olson, for a snapshot of military interventions between 1953 and 1992 (figure 5.12).

What is your first impression of the map? What do you notice? What questions come to mind?

The Green Revolution Program

Perhaps the best case study to examine the critique of large-scale international development projects is the Green Revolution program. Beginning in the 1960s, the Green Revolution was an initiative to increase the global food supply and reduce world hunger by the use of chemicals and engineered crop varieties. Programs were supported by scientists, development professionals, and Western leaders concerned that such hunger would make countries vulnerable to communism.

The strategy of the Green Revolution was to introduce irrigation, mechanization, fertilizers, pesticides, and genetically modified high-yield varieties of food grain to increase production in poor countries. Rice and wheat were the forerunners in this experiment. These crops replaced smaller subsistence farming, especially in India, Mexico, Pakistan, and the Philippines.

Dependence on Overseas Solutions

Production did increase significantly. The production of maize, wheat, and rice almost doubled between the 1960s and 1990s, and fewer people experienced hunger (Conway 1998).

However, in order to achieve these high yields, farmers were required to apply imported varieties of pesticides and fertilizers, give additional nutrients to plants, and develop more efficient irrigation and crop management techniques. These methods created or increased poor people’s dependence on technological solutions created in the faraway laboratories and factories in the United States and other industrialized nations.

For example, the Indus Valley along the border with India and Pakistan became the breadbasket for wheat in India. However, the new high-yielding crop varieties were reliant on water, fertilizers, and pesticides. As in many other parts of the world, only farmers with more capital (and larger plots of land) were able to gain access to the money needed to buy the fertilizer, buy the pesticides or herbicides, and obtain water access. Therefore, instead of improving the lives of small-crop farmers, these programs often displaced them from their land. As time went on, those fertilizers and pesticides also polluted the soil and water in the area (Ahmad et al. 1973).

Dependence on Foreign Loans

Green Revolution funding was in part provided by the philanthropist organizations the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation, as well as the U.S. government (Patel 2013). In many cases, funding that governments needed to implement Green Revolution farming methods came from organizations like the World Bank. Those loans required that countries provide local farmers access to products from the donor nations.

Critics argue this benefited the donors more than the recipients and put poor farmers at risk when they become dependent on new technologies and then fail to earn enough with their crops to pay rising prices for seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Farmers in developing nations (figure 5.13) have been encouraged with generous loans to invest in expensive capital equipment they cannot afford to purchase or replace machinery parts when the loans disappear.

Crisis in India

An epidemic of suicides among farmers in India began in the 1970s and still exists today. The National Crime Records Bureau of India reported that a total of 296,438 Indian farmers committed suicide between 1995 and 2013 (Parvathamma 2016). Many attribute these deaths to farmers’ inability to escape the cycle of debt created by their involvement in high-tech agriculture.

While it is difficult to track reasons for suicide, and suicide is often prompted by more than one life circumstance, some data collected by the Institute for Social and Economic Change do point to debt and high-tech agriculture as a main cause. Their survey of 528 farming families found that while unmet expectations of more credit and failure to get better crop prices contributed to many suicides, farm indebtedness was considered the major triggering factor in most of the cases (Manjunatha and Ramappa 2017).

As colonialism remains in the form of neocolonialism, the effects of the Green Revolution remain in the form of lingering multinational corporate control over production processes and resources needed for this kind of farming. In the 1990s, this control became more pronounced as patent protections began to be granted to private companies that develop and market genetically modified seeds. For example, the company Monsanto developed genetically modified corn and soy varieties that produce higher yields, but they require the use of Monsanto’s herbicide, forcing farmers to be dependent upon Monsanto products. With this change, the Green Revolution became a “Gene Revolution” (Food First n.d.).

Going Deeper

- For more information on the School of the Americas/WHINSEC, watch the two videos “School of Assassins 1/2” [Streaming Video] and “School of Assassins 2/2” [Streaming Video].

- To learn more about the Latin American Cold War, watch this 6:29-minute video, “Dictators and Civil Wars: The Cold War in Latin America” [Streaming Video], and see other resources by Retro Report 8 [Website]. Find a transcript of the video here [Website].

Licenses and Attributions for Mixed Impacts of Foreign Assistance, Humanitarian Aid, and Development

Open Content, Original

“Mixed Impacts of Foreign Assistance, Humanitarian Aid, and Development” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.8. “Screenshot of USAID’s Interactive Map of U.S. Foreign Assistance” by ForeignAssistance.gov is in the public domain.

Figure 5.9. Hardworking midwives at the Dila Health Center in Ethiopia is on Flickr, by USAID Ethiopia, and licensed under CC by 2.0.

Figure 5.11. “A Protestor, Dressed for a Staged Funeral Procession” by Steve McFarland is on Flickr and licensed under the CC BY-NC 2.0 license (left). “A Group of Protestors Staging Civilian Victims” by Caravan 4 Peace is on Flickr and licensed under CC by 2.0 (right).

Figure 5.12. “Screenshot of Cold War in Latin America – Interactive Map” by David Olsen (modification: overlay of “Interactive icon” by Thomas Shafee) is licensed CC BY.

Figure 5.13. “Woman Tobacco Farmer” by Adam Cohn is on Flickr and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.10. “How Junk Food Is Transforming Brazil” by The New York Times is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

aid given by a national government to countries in need.

aid to alleviate suffering and mitigate the effects of disaster provided by governments and non-governmental organizations for a short-term period until longer-term help can be provided by local governments or other institutions.

the people at the top of the income and wealth distributions in the world

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions.

a philosophical and economic ideology within the socialist framework that advocates for public rather than private ownership, especially of the means of production.

the government agencies, non-governmental organizations, philanthropic private businesses, individuals, and their actions, working to address poverty and inequality at a global scale.

an initiative to increase the global food supply and reduce world hunger by the use of chemicals and engineered crop varieties.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

a newer form of colonialism in which colonial powers maintain their economic and political dominance over former colonies through debt, trade agreements and corporate influence but without formal political control.