6.3 What Is an Economy?

An economy is a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society. That’s a bit of a mouthful; let’s look at an example.

Imagine again that you’re still in that coffee shop we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. It is pretty remarkable to consider how many people’s work went into your experience. For one thing, people had to grow that coffee, then harvest it, process it, roast it, ship it, grind it, and brew it. All along that line of production, other people had to contribute to the process, manufacturing tractors, roasting equipment, shipping containers, and ships. Some folks had to drill for oil, while others refined it. Others logged the forests that ended up in the napkin on your table. That entire complex web of relationships forms the economic system.

Since most people in the world live in a capitalist economy, most of the people doing that labor are wage workers—employees of various businesses. Each of those companies are competing to make profits for the owners of the businesses—the central goal of all capitalist enterprises.

Consider for a moment the number of social issues entangled within these economic relationships. Any list would have to include the wages and working conditions of all the people from seed to espresso. It would surely include the environmental impacts of coffee plantations, global shipping, and mass consumerism. It might even entail questions of corporate power and its effects on democracy. The economy, in short, is entangled with nearly every social issue we face.

Types of Economic Systems

The two major economic systems in contemporary societies are capitalism and socialism. In practice, no one society is purely capitalist or socialist, so it is helpful to think of capitalism and socialism as lying on opposite ends of a continuum.

Capitalism, as introduced in the previous section, is an economic system in which the means of production are privately owned. By means of production, we mean everything—land, tools, technology, and so forth—that is needed to produce goods and services (figure 6.2). Advocates of capitalism argue that this economic system enables individual freedom and that the desire for profit incentivizes innovation and economic prosperity.

Socialism, on the other hand, is an economic system in which the means of production and natural resources are collectively owned, usually controlled by the government (figure 6.3). Whereas the United States has several airlines that are owned by for-profit airline corporations, a socialist society might have one publicly owned and funded airline tasked with providing air travel to the population at little or no cost. Advocates for socialism argue that public ownership enables economic activity for the common good, not just the wealthy, thus providing a higher living standard for most people and a more stable economy.

Communism is often considered a type of economy, but many thinkers disagree. That is, following its full and classical definition, not a single state has ever been communist. For example, the Soviet Bloc countries saw themselves as socialist and still on the road to communism. German philosopher and economist Karl Marx (1818–1883) is usually credited with the development of communism as an ideology. We will discuss more of his ideas in the next section.

At the least, most agree that communism is a philosophical and economic ideology within the socialist framework. Like socialism, it advocates for public rather than private ownership, especially of the means of production.

During the Cold War, the meanings of communism and socialism were blurred by political leaders in the West. In order to stigmatize Soviet Bloc countries that dared to follow the Soviet model, they amplified the term “communism” as a pejorative (Kamusella 2021).

Societies’ economies mix elements of both capitalism and socialism in varying degrees. Some societies lean toward the capitalist end of the continuum, while other societies lean toward the socialist end. For example, the United States is a capitalist nation, but the government still regulates many industries to varying degrees and provides free public K-12 education. In another example, while China is formally communist, its economy is better described as state-managed capitalism, with a massive manufacturing industry catering to multinational corporations.

Capitalism and Socialism: Critical Comparisons

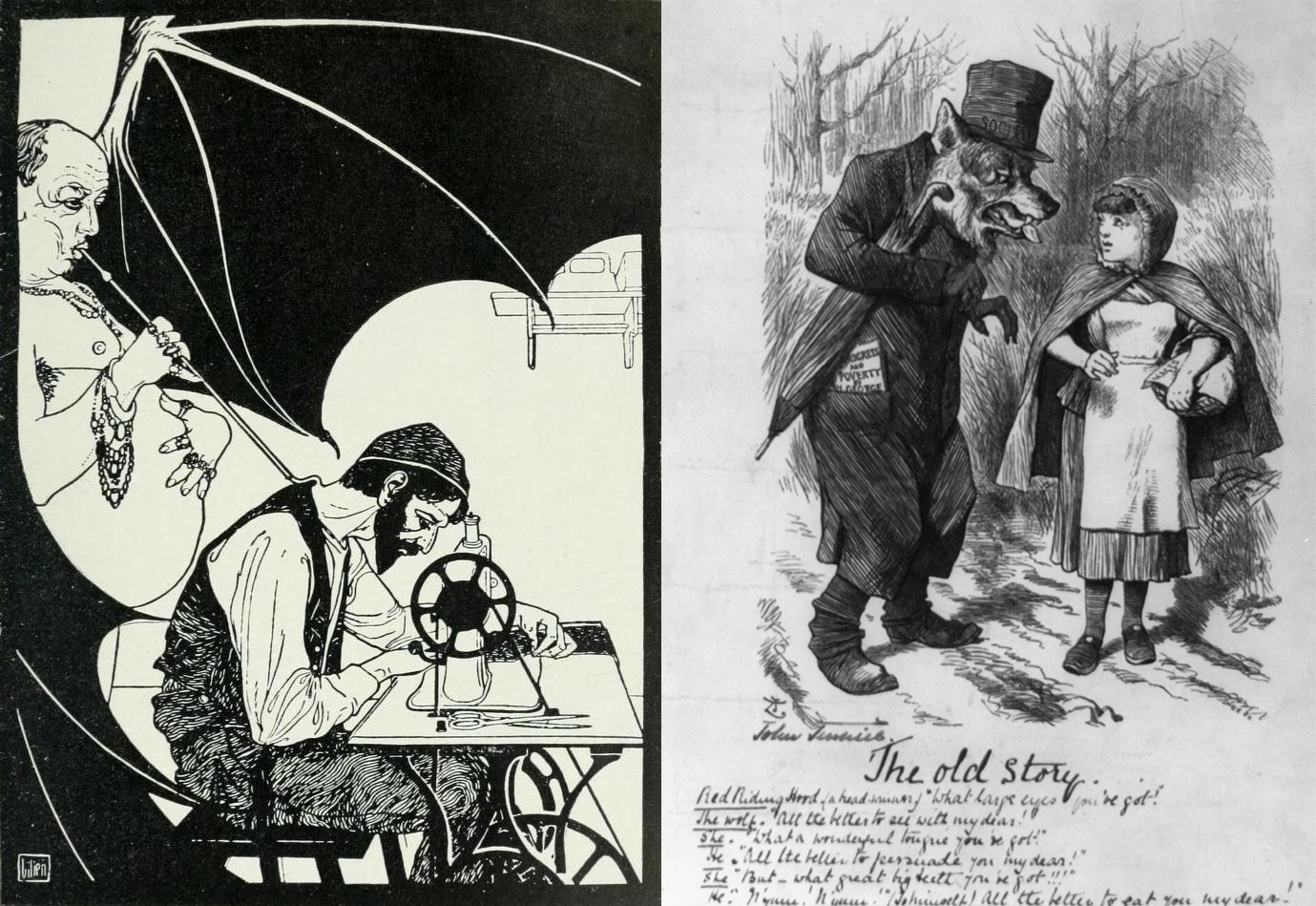

Capitalism and socialism, as ideologies and economic systems, have been debated for over a century (figure 6.4). Let’s examine some criticisms of each to better understand them. Take a look at the ideas below. What do you notice about the critiques?

Critique of Capitalism

Exploitation: “Capitalism fosters exploitative relationships between workers and owners of production.”

Alienation: “Workers are unable to determine their own destinies, define relationships with other people, nor own items, goods, and services produced by their own labor. This creates a feeling of estrangement from aspects of their human nature.”

Economic inequality: “A small minority benefit at the expense of many.”

Anti-democratic: “Capitalism leads to an erosion of human rights.”

Incentivization for war: “New markets and resources are required for capitalism to exist. This motivates nations to enter into war.”

Critique of Socialism

Equality: “Socialism does not protect equity across social locations. The establishment of an equal society would have to entail strong coercion.”

Rights: “Political, economic, and human rights need to be curtailed to achieve socialism.”

Freedom: “Socialism infringes upon private ownership of the means of production.”

Organizing a complex economy: “The means of production are controlled by a single entity, so approximating prices for capital goods is not possible.”

Technology: “Socialism slows or stagnates advances in technology due to reduced incentives.”

Licenses and Attributions for What is an Economy?

Open Content, Original

“What Is an Economy?” by Ben Cushing and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

The opening section of “Types of Economic Systems” is adapted from “Types of Economic Systems” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by the University of Minnesota, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Excerpts made, and edited for consistency.

Figure 6.2. Automobile Industry by William Gropper is on Flickr by Smithsonian American Art Museum and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 6.3. Our Life by Walter Womacka is on Wikimedia Commons and licensed under CC BY 3.0 US.

Figure 6.4. The Vampire, by E. M. Lilien is on Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain (left). 1884 cartoon by John Tenniel is found at the Library of Congress with no known restrictions (right).

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

a type of economic and social system in which private businesses or corporations compete for profit. Goods, services, and many beings are defined as private property, and people sell their labor on the market for a wage.

an economic system in which the means of production and natural resources are collectively owned, usually controlled by the government.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a philosophical and economic ideology within the socialist framework that advocates for public rather than private ownership, especially of the means of production.