7.3 The Study of Healthcare as an Institution

The World Health Organization defines health as not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (“WHO Remains Firmly Committed” n.d.). Health is the extent of a person’s physical, environmental, emotional, mental, and social well-being. This emphasizes that health is a complex concept that involves not just the soundness of a person’s body but also the state of a person’s mind and the quality of the social environment in which they live. The quality of the social environment can affect a person’s physical and mental health, underscoring the importance of social factors for both these aspects of our overall well-being. Our healthcare systems are designed to provide care to members and support these aspects of well-being.

As an institution, healthcare refers to the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services. So sociologists will study the problems, worldviews, and policies related to the goals of providing health. To examine healthcare in the United States, we can group our healthcare systems into three parts. One part of that system includes community care, the care that members of society offer for each other, such as parents and community members providing for a sick child at home. A second part involves health care providers delivering conventional care and services, often through private insurance companies. The care via insurance is delivered to individuals and families directly, through employers, or as a public service. The third part involves alternative care. Practitioners are most often naturopathic doctors and acupuncturists. They usually provide care outside of our national system, but laws are changing to include them in insurance plans.

Sociologists examine how well healthcare as an institution serves the needs of society. In this section, we’ll illustrate two ways they engage in that inquiry: through policy evaluation and through the social construction of illness with medical sociology.

Policy Evaluation

When sociologists examine U.S. health care provided through private insurance companies, they tend to assess how well certain policies meet health needs. For example, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (usually referred to as the ACA) was enacted in 2010 with the aim of ensuring that all U.S. citizens have access to affordable health insurance. Considerable studies have been conducted on how well it accomplished that goal. The ACA can give us a snapshot of how sociologists would inquire about and evaluate policy related to healthcare.

Dr. Wendy Hellerstedt, professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota, outlines key reasons why the ACA was needed:

Compared with other countries, the U.S. has a much stronger focus on diagnostic and treatment-related technology than on primary prevention. Many believe that this focus has translated into our high rates of potentially preventable causes of morbidity and mortality, such as obesity, and explains our poor international ranking in infant survival and in life expectancy. We also have deep social disparities in health outcomes.…Such disparities have complex [causes] that may not have been completely addressed by medical care (Hellerstedt n.d.).

ACA policies provided public preventative health care that, in the long term, was expected to reduce disparate health outcomes among economically and socially vulnerable citizens. The ACA also expanded Medicaid, the joint federal and state program that helps cover medical costs for some people with limited income and resources. Finally, it lowered the cost of health care in general.

The ACA also changed some of the ways insurance companies can operate. It prevents insurance companies from turning you down or drastically hiking your rate for pre-existing medical conditions. The policy ensures that you can’t be turned down for any reason, and costs are expected to be contained. The ACA marks a significant change to the healthcare system in the United States.

So, what do we know about how the ACA impacted health outcomes, particularly across social locations? The ACA has dramatically improved health insurance coverage across the United States (Kessler 2015). Researchers at the National Health Interview Survey found that the overall number of U.S. residents without health insurance dropped to a record low of 7.7 percent in the first three months of 2023 (Tsai 2023). We also know that the ACA likely prevented an estimated 50,000 patient deaths between 2010 and 2013 (National Health Interview Survey 2016).

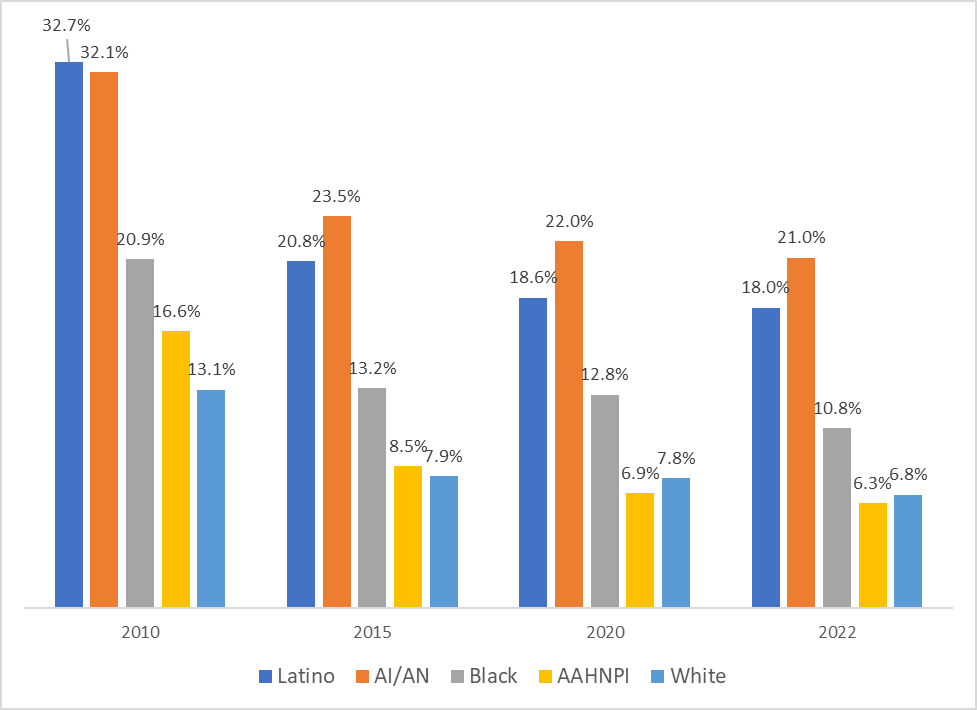

The ACA also addressed disparities in access to coverage. Prior to the ACA, the groups most likely to be uninsured were Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native populations (AI/AN in figure 7.4) and Asian-American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander populations (AANHPI in figure 7.4). The rates of insured improved for each of these groups at a rate much larger than other ethnic groups (Buchmueller 2024).

However, we also know that over 26 million people remain uninsured, and uninsured rates vary substantially between racial and ethnic groups. It’s also important to keep in mind that being insured does not necessarily mean that you are healthier. And reducing disparities among the insured is not sufficient for eliminating disparities in health outcomes.

Medical Sociology

If sociology is the systematic study of human behavior in society, medical sociology is the systematic study of how humans manage issues of health and illness, disease and disorders, and health care for both the sick and the healthy. Medical sociologists study the physical, mental, and social components of health and illness. Main topics for medical sociologists include the doctor/patient relationship, the structure and socioeconomics of healthcare, and how culture impacts attitudes toward disease and wellness.

This section will focus on those cultural aspects of health: the underlying societal beliefs that have shaped health institutions today. This is the social constructionist approach we introduced in Chapter 2, applied to health. At first glance, the concept of a social construction of health does not seem to make sense. After all, if disease is a measurable, physiological problem, then there can be no question of socially constructing disease, right?

Well, it’s not that simple. The social construction of health emphasizes the sociocultural aspects of the discipline’s approach to physical, objectively definable phenomena. In other words, “What we take to be the truth about the world importantly depends on the social relationships of which we are a part” (Gergen 2018:7).

We’ll explore what sociologists Peter Conrad and Kristin K. Barker have named as the main themes of study in this field: the cultural meaning of illness, the social construction of the illness experience, and the social construction of medical knowledge (Conrad and Barker 2010).

The Cultural Meaning of Illness

Cultural ideas play a significant role in how, as individuals, we experience illness. They also greatly influence the institution of healthcare in the United States. Many medical sociologists contend that illnesses have both biological and experiential components. The experiential component is in large part related to the cultural meaning we associate with illness. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

The first is that we establish and communicate the meaning of illness through labels. Society, through culture, determines which illnesses can receive the label of disability and which cannot. Society also decides which disabilities are deemed contestable. That is, some medical professionals, based on their perspectives, may find the existence of certain ailments questionable (Conrad and Barker 2010). Depending on the opinion of the medical professional, disorders like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome may be either true illnesses or only in the patients’ heads. This dynamic can affect how patients seek treatment and what kind of treatment they receive.

The second way we establish and communicate the meaning of illness relates to stigmatization. (We introduced stigmatization in Chapter 3 as the labeling or spoiling of an identity, which leads to ostracism, marginalization, discrimination, and abuse.) Society constructs ideas of which illnesses are stigmatized and which are not. Then society decides what the sanctions will be against those carrying stigmas. Many assert that our society and even our healthcare institutions discriminate against certain diseases—like mental disorders, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), sexually transmitted infections, and skin disorders (Sartorius 2007).

The social stigma related to a disease may keep people from seeking help for their illness, making it worse than it needs to be. When they do get care, the stigmatization of illness often has the greatest effect on the patient and the kind of care they receive. Facilities for these diseases may be subpar or patients may be segregated from other health care areas or relegated to a poorer environment.

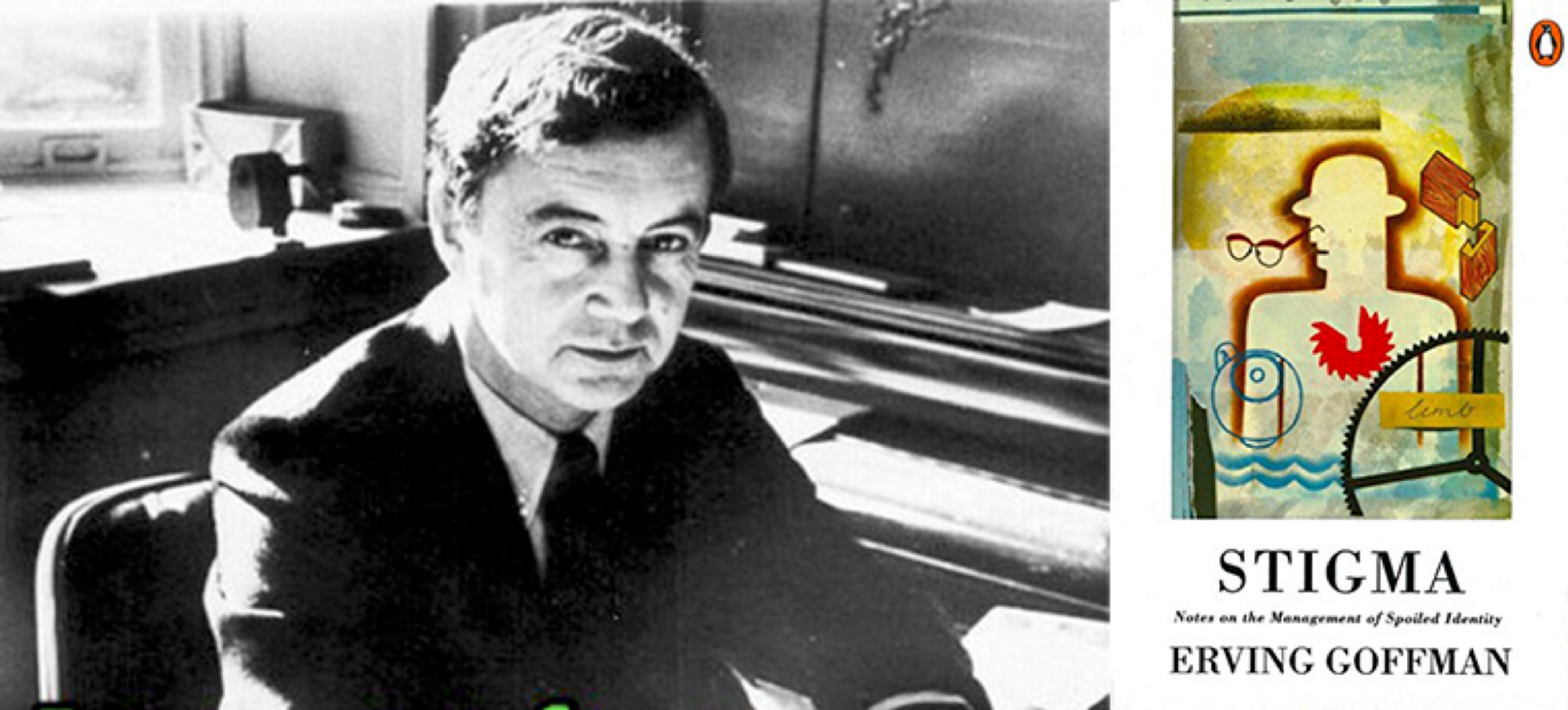

Sociologist Erving Goffman (figure 7.5) described how, due to this exclusion, social stigmas hinder individuals with illness from fully integrating into society. He believed that the stigmatization of illness also influences a person’s self-conceptions, and they become primarily concerned with the management of their identity.

Similar to Charles Horton Cooley’s “looking glass self” theory, Goffman noted that people who are stigmatized assume this exclusionary perspective of society as they develop their identity. That is, their identities are shaped based on how they perceive society views them, leading them to see themselves as separate from “normal” society. How they manage this illness stigma—how they conceal it, disavow it, or claim a more favorable social identity—depends largely on such factors as the visibility of the stigma and how well they are able to control information about themselves.

One way to observe this stigmatization and exclusion is by looking closer at mental illness. In the United States, mental illness is severely stigmatized. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (“Criminalization of People with Mental Illness” n.d.), less than half of people with mental illness receive help for their disorders. People avoid or delay seeking treatment due to concerns about being treated differently or fears of losing their jobs and livelihood. Even more devastating, the stigmatization of mental illness often also leads to the criminalization of people when they are suffering from mental health crises. The National Alliance on Mental Illness reports:

People with mental illness are overrepresented in our nation’s jails and prisons. About 2 million times each year, people with serious mental illness are booked into jails. Nearly 2 in 5 people who are incarcerated have a history of mental illness (37% in state and federal prisons and 44% held in local jails).

Many people with mental illness who are incarcerated are held for committing non-violent, minor offenses related to the symptoms of untreated illness (disorderly conduct, loitering, trespassing, disturbing the peace) or for offenses like shoplifting and petty theft (“Criminalization of People with Mental Illness” n.d.).

While stigmatization exists in most parts of the world, there are communities that value mental illness differently. Malidoma Somé (1956–2021) was an Elder and spiritual leader from the nation of Burkina Faso. He was specifically from the cultural region of Dagara, which covers areas of Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Côte d’Ivoire.

In 2015, Somé spoke in a video about his experiences visiting a psychiatric hospital. He noted the stark contrast between how the patients there were treated and how people experiencing mental health challenges are treated in Dagara Land. Watch the 5:01-minute clip, “Answering the Healer’s Call” [Streaming Video] (figure 7.6). As you do, pay attention to the meaning that the Dagara people hold for mental and spiritual struggles and those who experience them.

In the United States, the same degree of stigma is applied to harmful drug use. The stigma of harmful drug use often carries connotations of character and morality. This is despite the efforts of drug and alcohol counselors and other support practitioners to convey it as an illness. Both those suffering from mental health challenges and those suffering from harmful drug use suffer discrimination based on these stigmas.

Construction of the Illness Experience and Medical Knowledge

Let’s look at two more ways we socially construct illness. The first is our experience with illness. We create meaning out of our personal struggles living with illness. For example, for some, a long-term illness can make their world smaller, more defined by the illness than anything else. For others, illness can be a chance for discovery and reimagining a new self (Conrad and Barker 2010).

An important observation of the illness experience relates to people with AIDS. When AIDS swept the world in the 1980s, it was labeled as the fault of gay men whose illness resulted from what was perceived as promiscuity (Isay 1987). As such, AIDS was originally termed “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRIDS) by the U.S. government, and it wasn’t renamed AIDS until 1983. It was also widely assumed that the gay men who suffered from the disease were largely white, while in fact, minorities suffered disproportionately from the disease (Royles 2017).

The racism prevented Black communities from recognizing the growing crisis sooner and from getting the care they needed. Similarly, homophobia obscured the fact that AIDS reached people in all social locations, preventing important outreach to people other than gay men (Royles 2017). For those who were part of groups vulnerable to AIDS, communications from the federal government and other stations of power drove a sense of shame and stigma for their illness experience.

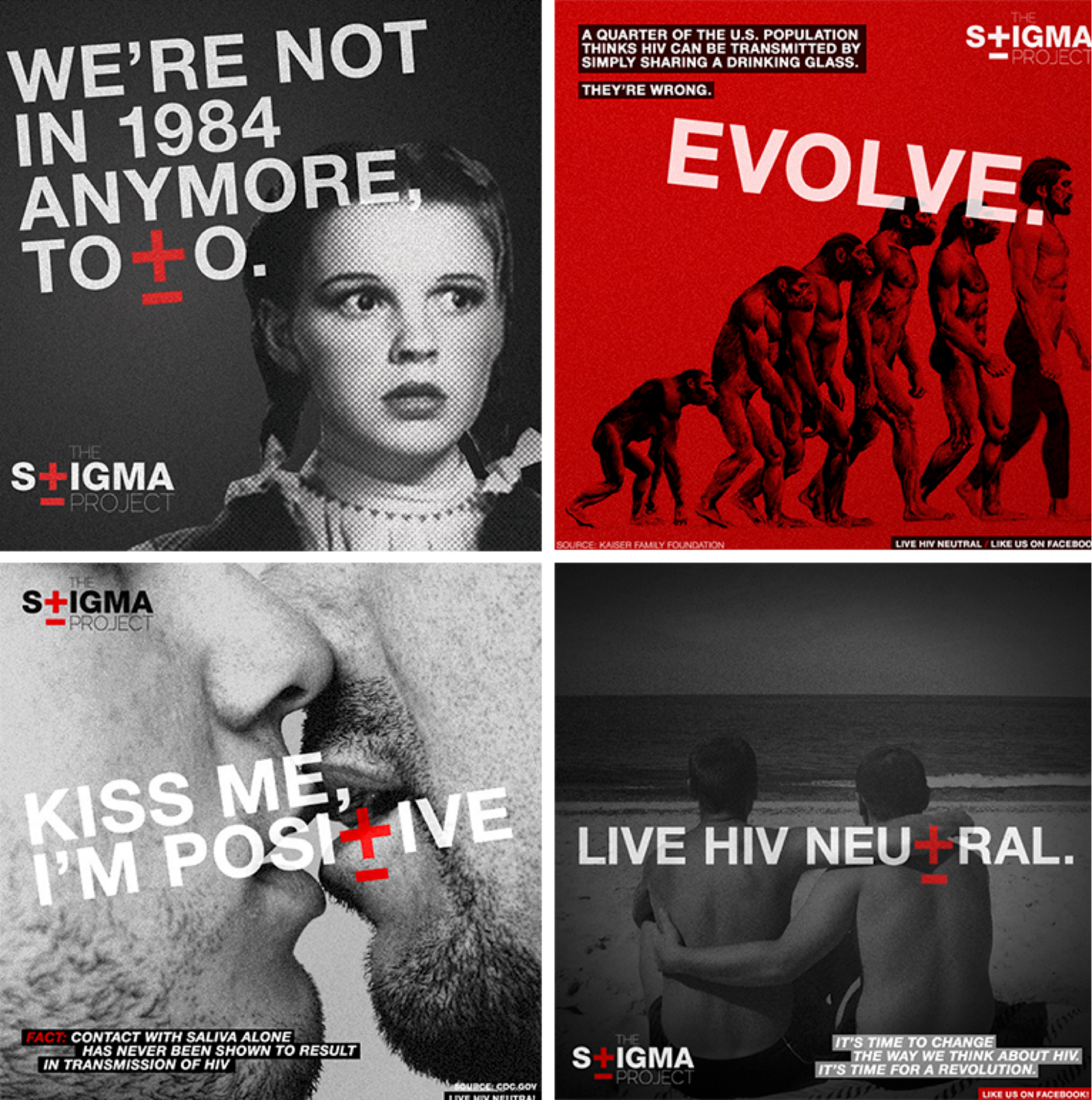

Over time, attitudes have shifted. This is in part due to organizations like the Stigma Project, which uses social media and advertising to promote shifts in attitudes around human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS (figure 7.7).

In addition to tackling societal stigma about HIV and AIDS, the Stigma Project aims to redirect the personal experiences of those who are HIV positive. They developed a campaign they call “HIV Neutral”:

To truly live “HIV Neutral,” we must begin shifting towards a new way of thinking about HIV/AIDS. Moving away from thoughts full of death and sadness and towards thoughts of life and hope for the future.

“HIV Neutral” is a state of mind regardless of your status, in which you are informed and aware of the constantly evolving state of HIV/AIDS.…Because HIV is now classified as a chronic manageable condition, treatment is now focused on people living full and healthy lives (“The Stigma Project” n.d.).

A second way we socially construct illness relates to medical knowledge. We decide as a society which health experiences need professional or product support and which do not. This meaning-making often happens with the influence of people in power in the medical and pharmaceutical world.

For example, medicalization occurs when human problems or experiences become defined as medical problems. Some diagnoses become accepted as medically valid and are used to define and treat patients. Women often find their natural reproductive functions (e.g., pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation) to be medicalized (Barker 1998; Riessman 1983; and Riska 2003 as cited in Conrad and Barker 2010).

People who are gay are also subject to their sexual expressions being medicalized (Conrad and Schneider 1992). When the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was first published in 1968, it listed homosexuality as a mental disorder. Today, all of the major medical organizations agree that homosexuality is not an illness or disorder, but a universal form of sexual expression. However, it was not completely removed until 1987 (Mayes 2005). In Chapter 9 we’ll discuss conversion therapy, a practice that strives to change peoples’ sexual orientation that is still promoted today.

The way that we socially construct illness influences the institution of healthcare. And the way our healthcare system is built shapes our personal experiences with our health. It shapes how well we are cared for when we are sick or have a disability, whether or not we are able to remain an integral part of society, and how safe we are. Each of these experiences is also influenced by our social location.

Going Deeper

To better understand how mental illness is criminalized in the United States, watch the 22:18-minute video “Mental Illness in America” [Streaming Video].

Also see the National Alliance for Mental Health infographic “Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System” [Website].

Licenses and Attributions for The Study of Healthcare as a Social Institution

Open Content, Original

“The Study of Healthcare as a Social Institution” by Avery Temple and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Medical Sociology” is a remix of “The Social Construction of Health” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns in Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax and Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, which are licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Avery Temple are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include minor revisions and expansion.

The first six paragraphs of “The Cultural Meaning of Illness” are adapted from “The Social Construction of Health” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns, Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include minor revisions and expansion, with photo added.

“Construction of the Illness Experience and Medical Knowledge” is adapted from “The Social Construction of Health” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns, Introduction to Sociology 2e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include minor revisions and expansion, with photo collage added.

Figure 7.7. Image (Toto) “We’re Not in 1984 Anymore, Toto” by The Stigma Project is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. “Evolve” by The Stigma Project is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. “Kiss Me” by The Stigma Project is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. “Live Neutral” by The Stigma Project is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 7.4. Uninsured rates by race and ethnicity from 2010 to 2022 is published by Health Affairs and included under fair use.

Figure 7.5. “Erving Goffman” is on Wikipedia, and included under fair use (left). Image of Stigma:Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity by Erving Goffman is on Wikipedia, and included under fair use (right).

Figure 7.6. Malidoma Patrice Somé is published on the “Answering the Healers Call w/ Malidoma Somé” Facebook page and included under fair use (left). Screenshot of What a Shaman Sees in A Mental Hospital is from an image published by Academia (right) and included under fair use. Video “Answering the Healer’s Call” by Zayin Cabot is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the study of how humans manage issues of health and illness, disease and disorders, and healthcare for both the sick and the healthy.

a statistical estimate based on averages, of the number of years a person can expect to live in a certain region.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the labeling or spoiling of an identity, which leads to ostracism, marginalization, discrimination, and abuse.

the set of characteristics by which a person is recognizable or known by the society in which they live.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.