7.4 Government Services and a Disparity of Support

The degree to which we live safe lives is directly related to the access we have to resources that provide well-being. In addition to effective health care, those resources include reliable and safe housing, fresh and culturally relevant food, clean water, physical and mental stimulation, a secure home life, and connection to our surroundings and communities.

Reread what was listed in the previous paragraphs and note what you currently have access to within your own life as well as what you don’t. Take another moment and survey internally how much each of those necessities currently costs. How much does it cost you annually to access all or some of these? What feelings come up when you are thinking about this?

If you feel anxiety, fear, sadness, or anger, you are unfortunately not alone. It is rare, both internationally and nationally, for people to have the ability to secure all of what is necessary to achieve a holistic state of health, safety, and security? This is due to systems in place that create inequality and disparities among us. While most of us are familiar with these injustices, they often show up differently and at varying levels of severity depending on our social location.

Government is the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that the society needs. In “The Study of Healthcare as an Institution” we introduced how a sociological study of health can examine how well government addresses our health needs.

Government ideally provides other benefits for their citizens. It can provide indirect benefits such as economic stability and enforcement of national borders. Government also provides direct benefits such as education, transportation infrastructure, and support for people experiencing poverty or hardship. Those benefits are guided by laws and policies which can support or deny granting safety and security to residents. As decisions are made to pass them or block them, and the manner in which they are enforced, the values and prejudices of policy makers are revealed.

This section will focus on how the U.S. government addresses some basic safety and security needs beyond healthcare for residents. We’ll first offer a brief summary of the criminal justice and public assistance systems in the United States. Then with some examples we’ll explore the question, “How does class, race, gender, and sexual orientation influence the ability to receive the security and safety that government is asked to provide?”

This chapter will not discuss questions of diverse experiences related to citizenship status; however, that is also an important aspect to consider when evaluating the overall well-being of life in the United States. We’ll cover experiences related to immigrant status in Chapter 8 as we discuss education, and in Chapter 10 as we explore social movements.

The U.S. Criminal Justice and Public Assistance Systems

The U.S. government, like all industrialized countries, controls a criminal justice system. It is an organization that enforces the laws and legal codes of the United States. There are three branches of the U.S. criminal justice system: law enforcement, the judicial system, and the incarceration system. Police enforce laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level. Federal officers operate under specific government agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI); the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

The U.S. judicial system is divided into federal courts and state courts. As the name implies, federal courts (including the U.S. Supreme Court) deal with federal matters, including trade disputes, military justice, and government lawsuits. The incarceration system, more commonly known as the corrections system, is responsible for removing individuals from the public who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offense.

While the U.S. military is not formally a part of the U.S. criminal justice system, scholars and activists have identified it as a major component of the criminal justice system. For example, the Coast Guard branch of the military can be utilized to enforce federal laws or restrictions.

The U.S. government is also in control of many social service systems. The largest take the form of public assistance and welfare (such as food stamps, Medicaid, and unemployment). Like many countries, in the U.S. social services are paid for by the taxes and labor of those residing within the country. When working well, they promote the health and well-being of individuals by helping them to become more self-sufficient; strengthening family relationships; and restoring individuals, families, groups, or communities to successful social functioning.

Fundamentally, if as an institution, it is the government’s role to care for the safety and security of a society then it must contend with inequalities and inequities of that society. Let’s look at a few that are more evident in the U.S.

Class Inequality

In Chapter 3, we introduced class as the set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation. Your class can have a profound impact on your life. It allows or restricts the opportunities and resources available to you. For example, class differences, exacerbated by increasing systemic wealth inequality, have created massive disparities between people’s ability to access healthy and culturally diverse foods, have a healthy workload, and acquire reliable shelter.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) states that 30 to 40 percent of the food supply in the United States is wasted (USDA n.d.). While concurrently, we know that 13.5 percent (18.0 million) of U.S. households were food insecure at some time during 2023. We also know that single parents, Black people, and Latinx people experience food insecurity at substantially higher rates (USDA 2021).

What’s important to note with these data is that “food security” simply means access to food; it does not include access to culturally relevant and healthy food (figure 7.8). If we include this criterion in our ideas of health, then many families within the United States struggle to obtain true food security (USDA 2015).

While mental and physical stimulation is necessary for a well-rounded life, the United States currently has a problem with overworking. Colleagues at Stanford University researched the question of overwork and found that pre-COVID people working long hours are two and a half times more likely to experience depression than those who work an eight-hour day. Working that much particularly increases your likelihood of having coronary heart disease. They also found that work-family conflict increases the odds of reporting poor physical health by 90 percent (Schulte 2022).

Most of us are familiar with the terms “side hustle,” which means additional jobs, and “grind culture,” or working as much and as often as possible to become financially stable. These terms come from an underlying issue with our class structure that forces us to work for fear of being in poverty, even if it is unhealthy for us (figure 7.9). NPR reports, “Between 2000 and 2016, the number of deaths from heart disease due to working long hours increased by 42%, and from stroke by 19%” (Chappell 2021).

You may have heard the phrase, “Housing is a human right.” This phrase holds truth—housing or shelter is not simply a commodity but in fact a requirement to survive. However, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development reported that in 2023, more than 650,000 people in the United States lack permanent shelter (figure 7.10). That’s the highest number since at least 2007 (Department of Housing and Urban Development 2023).

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many states mandated stay-at-home orders. But what happens when you do not have a home to shelter in place? The likelihood of becoming infected with COVID-19 was much higher for unhoused people than for those with secure shelter. Pandemic aside, people experiencing houselessness have lifespans shorter by about 17.5 years on average than those recorded for the general population in the United States (Perri et al. 2020).

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the main federal agency that works to address houselessness. (More frequently, the word houseless is used in place of homeless, to make the distinction between a house and a home. People described as without homes are not necessarily without homes.) HUD provides funding for emergency shelters, permanent housing, and transitional housing.

Why do the human needs of healthy food, a healthy work life, and shelter security remain elusive in the U.S.? The answers are complex, and opinions vary greatly. However, class inequality is a significant source of the challenge. This poses the fundamental question: What role does government have in providing policy and programs to counter such disparity in well-being? What options do governments have? Taking a closer look at shelter and insecurity in the U.S. can give a better idea of the kinds of programs and policies that could be put in place to address inequities of this kind.

Houselessness is a complex issue that requires multi-faceted solutions to address the myriad reasons that individuals may be unsheltered. However, many houselesss advocates claim that it will only be solved with the political will to install housing first programs. The housing first strategy provides permanent housing to people experiencing houselessess. It is guided by the belief that people need basic necessities like food and shelter before attending to anything less critical, such as getting a job, budgeting, or tackling substance use challenges.

Housing first programs require providing more up-front costs to implement than most programs currently in place. But they have proven to be less costly in the long run as they shorten stays in hospitals, residential substance abuse programs, nursing homes, and prisons. In short, there are solutions to houselessness; they just require the political will to fund them that the U.S. has not achieved.

In 2019 the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, Leilani Farha, announced some other ways government could do better in addressing houselesssness in the U.S. She pointed to policies that offer “financial supports” and tax breaks to companies to encourage investment in housing, but that don’t include investment in housing for the most vulnerable populations. She also notes that local governments have failed to enact legislation such as rent control and policies linking housing prices with minimum wage regulations (Farha 2019).

Some severe lived experiences are revealed when we look closely at class in the United States. Limited access to healthy and cultural foods, reliable shelter, and overworking are experienced by too many. Considering the severity of class inequality in the United States and the consequences related to basic human needs such as food, housing, and a healthy workload, it’s crucial to examine what the responsibility of the government is to address these hardships.

The Impact of Racism

In Chapter 3, we explored institutional racism and structural racism. Both refer to the unfair policies and discriminatory practices that exist to produce racially inequitable outcomes for people of color and advantages for white people. In the United States, we can trace some of those policies and practices to government systems. Three examples are the access people have to clean water, treatment by police, and the incarceration system.

The consequences of racism affect every area of our lives. As you read, ask yourself: What experiences listed in this section remind me of crises of racism that my community or I have faced? How did we get through them? In what ways did we come together or implement creative solutions?

Access to Clean Water

As discussed by Marccus Hendricks, an associate professor of urban studies at the University of Maryland, “The legacy of racial zoning, segregation, [and] legalized redlining have ultimately led to the isolation, separation and sequestration of racial minorities into communities [with] diminished tax bases, which has had consequences for the built environment, including infrastructure” (Costley and Pettus 2022).

One of the most necessary infrastructure needs is the provision of water. Unfortunately, access to clean and safe water is not the reality for all in the United States. This may be a scenario that you associate with countries of the global majority. However, systemic racism in the United States created an ongoing water crisis in Jackson, Mississippi.

After a river flooded from severe storms in 2022, the city’s largest water treatment facility failed, leaving approximately 150,000 residents without access to safe drinking water (Flavelle 2022). Hospitals, fire stations, and schools were also affected. The governor issued a state of emergency, and President Joe Biden declared it a federal disaster to trigger federal aid.

However, the governor withdrew the state of emergency on November 22 of the same year. This crisis continues today. The Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights organization, points to local government for blame, “as Mississippi’s governor and white-dominated Legislature continue to block funds necessary to repair the system” (Mississippi City’s Water Problems Stem from Generations of Neglect 2023).

Watch the 2:33-minute video “Racism Seen as Root of Jackson Water Crisis” [Streaming Video] for the story (figure 7.11). As you do, pay attention to how the student organizers explain the reasons for the water crisis in their city.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tSPX01AkZSo

Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color frequently experience a lack of updated and efficient infrastructure in the United States. This can leave whole cities scrambling for solutions when their systems fail.

Discrimination, Law Enforcement, and the Incarceration System

Being cared for, protected, and treated fairly by state-sponsored systems is fundamental to a healthy and safe life. Regrettably, widespread police brutality and state violence stemming from prejudice, discrimination, and racism in the United States often means that these needs are unable to be met for many people of color, especially Black or African Americans.

We’ve explored institutional discrimination within the U.S. police systems and community response in several sections of this book. The 2020 George Floyd uprisings were one of the largest nationwide protests that the United States has experienced (Buchanan et al. 2020). The spark for the protests was the appalling murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by police in May 2020.

Police officers had apprehended Floyd over what was allegedly the use of a $20 counterfeit bill, during which Officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck and back for over nine minutes, suffocating him to death. The protests that this murder inspired continued well into the summer and, in some cities, throughout the year (see a mural and memorial to Floyd in figure 7.12). The police brutality that Black and African Americans experience on a daily basis has been a consistent issue since the end of slavery in the United States.

Related to discrimination within our criminal justice systems, another area that impacts safety is the U.S. incarceration system. The U.S. incarceration rate has grown considerably in the last 100 years. In 2008, more than 1 in 100 U.S. adults were in jail or prison, the highest benchmark in our nation’s history. And while the United States accounts for 5 percent of the global population, we have 25 percent of the world’s inmates, the largest number of prisoners in the world (Fair 2021). In 2021, 1,204,300 residents were behind bars in the U.S. (figure 7.13).

The U.S. incarceration system of today upholds the legacy of slavery. While Black people make up only about 12 percent of the population in the United States, they make up almost 40 percent of people who are incarcerated (“Inmate Race” 2024). Currently stated in the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution is the clause that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction” (United States Constitution).

By policing and imprisoning a significant portion of the population—a majority of whom are people of color—the incarceration system continues a legacy of exploitation and cheap or “free” labor. Watch the 2:33-minute video, “Mass Incarceration, Visualized” [Streaming Video] in figure 7.14 for an insightful discussion on U.S. incarceration rates, the inevitability of prison for certain demographics of young Black men, and how it’s become a normal life event. What trends do you see in incarceration rates, and what consequences do you notice?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u51_pzax4M0

The Impact of Sexual Orientation Discrimination

Like racism, gender and sexual orientation discrimination are things that many of us face in our daily lives. It can be discreet or overt, and embedded in cultural beliefs. Sometimes it can be hard to identify and unlearn. As in all institutions, gender and sexual orientation discrimination exist in the political structures of the United States, creating disparity in access to safety and security.

The U.S. legal system was built upon a religious framework that stigmatized and criminalized homosexuality. Historically, laws have been passed to restrict private sexual acts between consenting adults and to deny benefits and basic civil liberties to gay and lesbian individuals. Until 2020, discrimination against people who identify as LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual, and other identities) was legal in employment (Herek et al. 2007). While lawmakers are working on one, currently, there is no federal law that consistently protects LGBTQ+ individuals from housing discrimination.

When HIV/AIDS was declared a worldwide epidemic, discrimination became especially apparent. As we described earlier, the disease was at first incorrectly stereotyped to be a “homosexual” or “gay” disease, even though HIV/AIDS was and is diagnosed among people of all sexual orientations. ACT UP! was one of the first organizations to bring the mistreatment of people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS to the national political stage. They protested government agencies for a host of failures, including the high cost and lack of availability of HIV treatment, a lengthy drug approval process, and a lack of prioritizing diverse types of AIDS treatments (figure 7.15).

Same-sex marriages were illegal at the national level until 2015. Until then, same-sex couples were not able to receive the same federal benefits as heterosexual couples nor be entitled to the same legal protections. There are over 1,000 federal rights that protect married couples and their families. They include Social Security survivor and pension benefits, hospital visitation rights, medical decision-making rights, inheritance rights, family leave under the federal Family Medical Leave Act, and end-of-life decisions (ACLU n.d.).

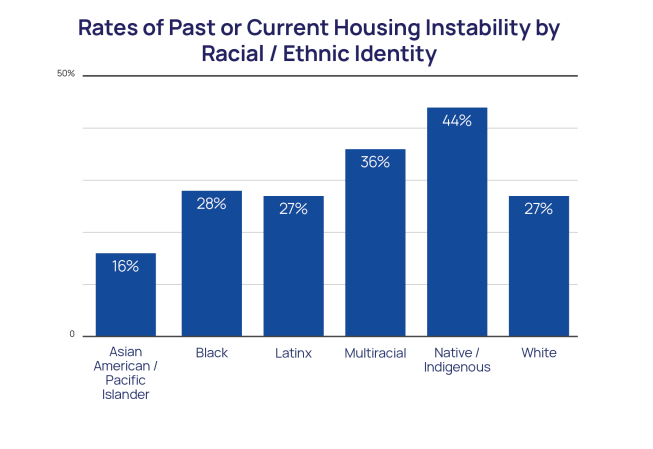

In addition to discrimination, people who identify as LGBTQIA+ often experience compounded challenges from resource inequality. According to the Trevor Project, in 2021, 28 percent of LGBTQIA+ youth in the United States experienced houselessness or housing instability at some point in their lives (DeChants et al. 2021). Examining the intersecting social locations of LGBTQIA+ and race/ethnicity reveals more of the picture. For example, in 2021, nearly half (44%) of Native/Indigenous LGBTQ youth had experienced homelessness or housing instability at some point in their life (The Trevor Project 2022). See more rates of housing instability for LGBTQIA+ youth by race and ethnicity in figure 7.16.

These rates are staggering and can have life-threatening or deadly consequences. Statistics are often more severe for youth who identify as transgender. Watch the 2:23-minute film “A Road to Home” [Streaming Video]. It’s a trailer for a documentary that follows the journeys of six unhoused young LGBTQIA+ people over the course of 18 months (figure 7.17). What unique challenges do you notice the youth profiled in the video face?

There have been some significant gains in human rights protection for people who identify as LGBTQIA+. The granting of legal marriage rights was an enormous achievement. However, efforts at legislation that legitimize and legalize discrimination against people who identify as LGBTQIA+ continue. In 2023, over 520 anti-LGBTQIA+ bills were introduced by the legislature. This is more than has ever been introduced in the U.S. (Cullen 2023). Most of these recent bills target the basic freedoms of transgender people, particularly transgender youth.

Unfair policies and discriminatory practices are deeply embedded within the structure of government. This section only introduces a few examples of how those policies and practices create negligent and dangerous circumstances for people of color and for people who identify as LGBTQIA+. Ultimately, it requires civil society to monitor discriminatory laws and policies, counter initiatives that violate human rights, and fill in the gaps where government fails to provide services for safety and security for all.

Licenses and Attributions for Government Services and a Disparity of Support

Open Content, Original

“Government Services and a Disparity of Support” by Avery Temple is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Aimee Samara Krouskop contributed to content on houselessness.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 7.8. “Waiting in line for the freshest – and cheapest – produce on the street!” by Brian Godfrey, is on Flickr, and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 7.9. A man working late at night by Muhammad Raufan Yusup is on Unsplash and licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 7.10. “Homeless Veteran on the Streets of Boston, MA” is on Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Figure 7.12. “The George Floyd mural outside Cup Foods” by Lorie Shaull is on Flickr and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 7.13. “Number of Prisoners Per 100,000 People Around The World” is created by @theWorldMaps, published by https://brilliantmaps.com/ and is included under fair use.

Figure 7.15. “ACT UP 30th Anniversary March” is on Flickr, by Elvert Barnes, and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 7.11. “Racism Seen as Root of Jackson Water Crisis” by Stephen Smith, Associated Press, is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.14. “Mass Incarceration, Visualized” by Bruce Western, The Atlantic, is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.16. “Rates of Housing Instability for LGBTQ youth, by Race and Ethnicity” published in “Homelessness and Housing Instability Among LGBTQ Youth,” by The Trevor Project, is included under fair use.

Figure 7.17. “A Road To Home – Trailer” by Lumiere Productions is licensed under the Vimeo License.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the capacity to actively and independently choose and to affect change

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the labeling or spoiling of an identity, which leads to ostracism, marginalization, discrimination, and abuse.

the communities, groups, and organizations that function outside of government to provide support and advocacy for certain people or issues in society.