7.6 Alternative and Decolonizing Models for Health, Safety, and Security

We’ve organized this chapter to discuss three main human needs that we rely on institutions to support: health, safety, and security. We expect the institution of healthcare to provide medical services to prevent, diagnose, and treat health problems. It’s probably safe to say that most people in the United States expect the institution of government to provide safety in the form of protection against crime and violence. Many expect the institution of government to play a role in ensuring its residents have security such as stable shelter.

As we’ve explored in previous sections, when it comes to equity for health, security, and safety our concepts and the institutions and systems we build for them can improve. But what are the options? Let’s look at a few alternative perspectives and models: decolonization of policing, models that redefine public safety, and universal and accessible healthcare.

Universal and Accessible Healthcare

The ACA passed in 2011. Considering health systems in other industrialized countries offer the same benefits to citizens (and often more), it is a stretch to call it an alternate model of healthcare. However, it was the first time in the United States that a national program was approved to ensure that all citizens have access to affordable health care. One important tension arose while the passing of the ACA statute was being debated, however. Some decried that it would bring us closer to a system of socialized medicine. Others felt it didn’t go far enough to provide universal healthcare.

Under a socialized medicine system, the government owns and runs the healthcare system of a country. It employs doctors, nurses, and other staff and owns and runs the hospitals (Klein 2009). A prime example of socialized medicine is in Great Britain, where the National Health System has provided healthcare to all its residents since 1948 (figure 7.20). As we mentioned in Chapter 6, many people in the United States have negative connotations of the idea of socialism after political leaders in the West stigmatized the term during the Cold War. However, the United States already contains a number of socialized systems.

One socialized system in the United States that addresses healthcare is the Veterans Health Administration. Funding for the Veterans Health Administration comes from the federal budget, and the government controls its operations, including employing the practitioners. The United States also has two systems related to health that are, in a sense, socialized. Medicare is a government-run health insurance program for everyone over 65 that has existed since 1965.

Medicaid is jointly funded and administered by federal and state entities. It provides free or low-cost health coverage to low-income people and families, pregnant women, and people with disabilities. All three programs offer no-cost care funded through tax dollars. The only thing that separates Medicare and Medicaid from the true definition of a socialist program is that the government does not administer the care.

With universal healthcare, the government doesn’t necessarily own and administer the healthcare system. It is simply a system that guarantees healthcare coverage for everyone. Germany, Singapore, and Canada all have universal healthcare. Often, healthcare is publicly funded and administered by the government, but the care itself comes from private providers. Private providers are the main difference between universal healthcare and socialized medicine.

The basic principle behind socialized medicine and universal healthcare is that health is a human right for everyone. We all will need medical care at points in our lives, and as a society, we have a collective obligation to care for those who are infirm or vulnerable. While Medicaid, Medicare, and ACA programs are well known, there are other lesser-known programs that have emerged from these principles.

One example is the People’s Free Medical Clinics (PFMCs), organized and funded by the Black Panthers. The Black Panthers were a powerful organization that grew from the Black Power movement in the 1960s. The Black Power movement emphasized Black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration into dominant white systems. Their strategy was to secure their human rights by creating political and cultural organizations that served their interests. Many people know the Black Panthers as a militant socialist organization. What is not widely known is that they created free and accessible health programs throughout the country (figure 7.21).

PFMCs were designed to address the systemic discrimination that many Black people receive in hospitals and private medical practices, leading to a lack of care. It was also designed to address health disparities that Black people and other people of color experience in the United States. Many of the Black Panthers’ health programs remain in some shape or form today. For more information on the PFMCs, watch the first 6:46 minutes of this video, “The Black Panthers’ Overlooked Health Programs” [Streaming Video] from TIME (figure 7.22). As you do, consider what the legacy (the long-lasting impact) is of the PFMCs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCGA4TLaq8g

Many consider organizations like Occupy Medical and CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) (figure 7.23) as part of the legacy of the PFMCs. Both organizations are located in Oregon and aim to provide free health care, including crisis assistance, to anyone in Eugene or Springfield. Their success is apparent in the growth of their collectives and the services they provide to all people, but especially marginalized community members such as the unhoused.

Occupy Medical’s website states, “We believe that everyone, regardless of income or status, should have access to medical care without the fear of financial burden or being considered unimportant by their caregivers. We strive to listen to everyone who comes to our clinic, to build a positive culture in the community, and to give the best care possible at no cost to the city and the people” (“What is Occupy Medical?” n.d.).

Similarly, CAHOOTS describes itself as “a mobile crisis intervention team, designed as an alternative to police response for non-violent crises. CAHOOTS provides mobile crisis intervention 24/7 in the Eugene-Springfield Metro area. They provide services to stabilize patients who have urgent medical or psychological needs or require an assessment, information, referral, or advocacy. CAHOOTS also provides transportation for patients to their next location for treatment” (White Bird Clinic n.d).

Health, Resilience, and Resistance

Our orientation to nature, our economic systems, and our systems of health care are intertwined. Indigenous or First Nations economic systems generally have not relied on exponential growth and consumption to lead a healthy lifestyle. Many journals from early colonists describe the Americas as places with lush and ample resources. Indigenous Peoples had consistently managed and stewarded the land using techniques perfected throughout generations. Today, over 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity is currently stewarded by Indigenous Peoples (Raygorodetsky 2021). This is true, only because Indigenous Peoples have fought, resisted, and created new systems for protecting the land, its inhabitants, and their cultures.

Good health relies on a healthy environment. However, we all struggle with the loss of the natural environment because of five centuries of colonization that persists today. Because Indigenous identity is deeply connected to place and territory, the destruction of ancestral land is especially detrimental to the health and safety of Indigenous communities. Generally speaking, Indigenous cultures are rooted in place, tradition, and stewardship of the land. Because there are Indigenous Peoples on every acre of land that is habitable or has been habitable by humans, each act of destruction to the environment or peoples is also an act of destruction for the Indigenous Peoples who are from there.

A popular example of Indigenous resistance in the United States was the #NoDAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline) protests, otherwise known as Standing Rock (“No DAPL” 2021). The #NoDAPL movement began when the Standing Rock Sioux peoples decided to fight the construction of an oil pipeline that would be built on their ancestral land, destroy cultural resources, and violate century-old treaties made between the Tribe and the U.S. government. (Optional: Read more about the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe [Website].)

This led to intense protests where Indigenous Peoples, allies, and community members from all over the world came to occupy and resist the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. More than 300 people were injured, and hundreds were arrested by the U.S. government during these protests (Montare 2018). While the Dakota Access Pipeline is still in commission, the #NoDAPL movement paved the way for many contemporary Indigenous resistance movements in North America, such as #StopLine3.

First Nations in the United States, such as the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, as well as many others, have been resisting a Canadian oil company named Enbridge for nearly two decades and continue to do so today (“Stop Enbridge’s Line 5” n.d.). Figure 7.24 shows one protest sign of many. Line 3 and Line 5 are both massive pipelines that have already endangered critical ecosystems and ways of life in Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron. These pipelines break centuries-old treaties between the U.S. government and Tribes. They also endanger the wild rice, or manoomin, which is crucial for the health and spiritual identity of many Indigenous Peoples of that area (“Stop the Line 3 Pipeline” n.d.)

Indigenous Peoples’ resistance to colonialism, their displacement from ancestral lands, and the destruction of nature have occurred around the world since the arrival of colonists. These campaigns of resistance serve as a crucial reminder that the foundation of our health is reliant on the health of the environment.

Decolonization of Policing

In “The Impact of Racism” presented earlier, we explored how the U.S. policing and incarceration system is too often entangled with racialized practices. That is, racial disparities in policing persist, particularly in the threat or use of force (Wang 2022), and the incarceration system upholds the legacy of slavery (an extension and tool of colonization).

To many thinkers, these practices are built on a foundation of a colonial mindset. We described some aspects of that mindset in the Colonized vs. Indigenous Worldviews section. They include a prioritization of the individual and wealth, prioritization of people’s laws over the natural world, and an assumption that our safety needs to be controlled by the state.

To respond, a body of knowledge is being developed around ways of decolonizing many justice-related systems. Those systems include the courts, prisons, mental healthcare, the study of law and criminology, and policing. People from many professions, such as academics, social service practitioners, and elected government officials, are putting critical thought into damaging colonial worldviews that permeate these systems.

Considering what we’ve learned about the racialization of law enforcement, what does decolonization mean in the context of that system? Some thinkers focus on reform. They might look for better Indigenous and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) representation within police forces (figure 7.25). Others ask that we look toward alternative policing models and “community empowerment” (Porter 2016:561). They ask that agencies better reflect cultural and historical understanding and awareness of the communities in which they police. They see potential in community-based policing programs for building trust between communities and officers.

Reform strategies also might attempt to share authority with communities. Programs that involve First Nations and Inuit policing, and Indigenous patrols in Canada are examples of that model of policing. (Optional: Read more about Inuit communities [Website].) They strive to engage in meaningful collaboration with Indigenous communities in order to incorporate the current ideas and voices of those community members in their policies and practices.

Going further, reform might mean handing over full responsibility. For example, Canada implemented a First Nations Policing Policy (FNPP) in 1991. With that program, agreements are negotiated among First Nations and Inuit communities, provincial or territorial governments, and the federal government. Under such agreements, communities are responsible for managing their own police service, which is primarily staffed by officers of First Nations or Inuit descent (First Nations Chiefs of Police Association n.d.).

However, this reform only goes so far toward decolonization. First, there are significant limitations to these reforms. The primary limitation is in the fact that power remains in the same social structures and population that oppressed the communities involved. In addition, funding is a great challenge for these programs, and they rely on government budgets (What Does Defund the Police Mean? 2024). While programs like the FNPP are thought to give autonomy and self-governance to Indigenous communities, they continue to be restricted through excessive government control (Kiedrowski et al. 2017). Furthermore, these reform programs continue to be built within the framework of the same policing systems.

Because reform measures for policing only go so far toward decolonization, some police accountability groups might lobby for policing to be defunded (figure 7.26). Defundthepolice.org explains defunding as the redirection of funds “from institutions that kill, harm, cage, and control our communities, and investing in violence prevention and interruption, housing, healthcare, income support, employment, and other community-based safety strategies that will produce safer communities for everyone” (“What Is Defund the Police?” n.d.).

This worldview is reflective of decolonizing practices. First, it calls us to diminish our investment in a system that is built on harmful colonial values. For example, it acknowledges that our law enforcement systems are built within a white supremacist culture and history of slavery. Second, it’s a protest against the colonial value of prioritizing the individual. This value prevents us from acting for the well-being of others. Third, it counters the assumption that our safety needs to be controlled by the state.

Redefining Public Safety

The ideas about decolonizing policing through defunding also reframe the way we think about what public safety means. That is, it shifts our notion of creating public safety from punishment, violence, imprisonment, and control to providing care for peoples’ basic needs—especially those who are in crisis or vulnerable. As the Police Brutality Center describes, “…redirecting funds from police departments to social services and public health agencies better-qualified to address some public safety concerns eliminates the need for punitive policing by addressing the root causes of violent crime” (“What Is Defund the Police?” n.d.).

As we mentioned, some thinkers and activists take the question of our police systems another step further and call for abolition, or ending the practice and institutions of punishment. During the George Floyd uprisings, two main messages rose to the surface: 1) “Black Lives Matter,” and 2) “Abolish the Police.” People across the country rallied and joined each other in the streets to decry the violence that people of color, particularly Black people, experienced at the hands of the police. This movement was widespread because of the abolitionist work that had been happening on smaller scales for decades. These movements are more thoroughly reframing what public safety means.

Organizations like Critical Resistance (figure 7.27), Interrupting Criminalization, Transform Harm, and the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective have held these movements. They have created containers where communities build systems of safety that are not founded on racism, violence, or punishment. Coined and practiced by these collectives, some of the processes that are used are called “transformative justice” and “community accountability.”

Mia Mingus is the founder of the organization SOIL: A Transformative Justice Project. She defines transformative justice as a “political framework and approach for responding to violence, harm, and abuse.” It begins with a belief that oppression is at the root of all forms of harm, abuse, and assault, and it works to address and confront that oppression.

As a practice, it seeks to respond to violence without creating more violence. Some practitioners think of this process as a way of getting in “right relation,” or creating justice together. Responses and interventions don’t rely on law enforcement or the criminal legal system, and they actively invest in what we know prevents violence: healing, resilience, and providing safety for all (“Transformative Justice and Community Accountability” n.d.).

Related to transformative justice is community accountability. It’s a community-based strategy, rather than a police/prison-based strategy, to address violence within our communities. The organization INCITE! explains community accountability as a “process in which a community—a group of friends, a family, a church, a workplace, a neighborhood, etc.—works together to transform the conditions that reinforce oppression and violence. They might provide safety and support to community members who are violently targeted. Or they might address community members’ abusive behavior, creating a process for them to account for their actions and transform their behavior” (“Transformative Justice and Community Accountability” n.d.).

Watch the first 2:05 minutes of “What Is Transformative Justice?” [Streaming Video] (figure 7.28). You can hear more from Mingus there. How do you notice the practitioners define the scope and potential of transformative justice? (Optional: If you have time, it’s worth watching the entire video for a broader understanding of transformative justice.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-_BOFz5TXo

Both transformative justice and community accountability address harm in communities by focusing on healing the person who was harmed. Simultaneously, they work to fix the conditions that made the harm possible in the first place. In other words, these abolitionist programs work toward public safety in the United States by addressing the root causes that result in harm.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

In Chapters 3 and 8, we referred to Indigenous knowledge in the context of decolonization. As we decolonize practices and worldviews, the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples have room to be more valued in society. One way to refer to knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples is Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

TEK encompasses the wisdom, intelligence, innovations, and practices of Indigenous and local communities that have been passed down through generations. TEK focuses on the relationship of living beings with one another and with their environment. While not new to institutions in the United States, TEK is increasingly being considered as crucial for whole understandings of healthy human and environmental systems.

TEK Inclusion

In December 2022, a team from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy submitted a blog to the White House website. It announced a marked intention in shifting our colonial-based worldviews of health, security, and safety. The blog provided a definition of TEK and explains its value:

(TEK) applies to phenomena across biological, physical, social, cultural, and spiritual systems. Indigenous Peoples have developed their knowledge systems over millennia, and continue to do so based on evidence acquired through direct contact with the environment, long-term experiences, extensive observations, lessons, and skills.

This familial intimacy with nature enables the ability to detect often subtle, micro-changes and to base decisions on deep understanding of patterns and processes of change in the natural world of which people are a part. The information and summative historical and cultural ecology contained within Indigenous languages, practices, values, place names, songs, and stories hold data and knowledge that are relevant today (Daniel et al. 2022).

The blog also introduced new guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies to incorporate TEK in their work (figure 7.29). Created at a White House Tribal Nations Summit, the guidance recognizes that in order to make the best scientific and policy decisions possible, the federal government should value and find ways to respectfully include Indigenous knowledge. This was the first guidance document of its kind drafted by members of White House offices (Daniel et al. 2022).

The number of people with institutional power who recognize the need for Indigenous participation appears to be growing. They are often those who see limitations and concerns with our current systems, especially with those systems related to healthy human and environmental systems. One of the institutions illustrating this recognition is the government.

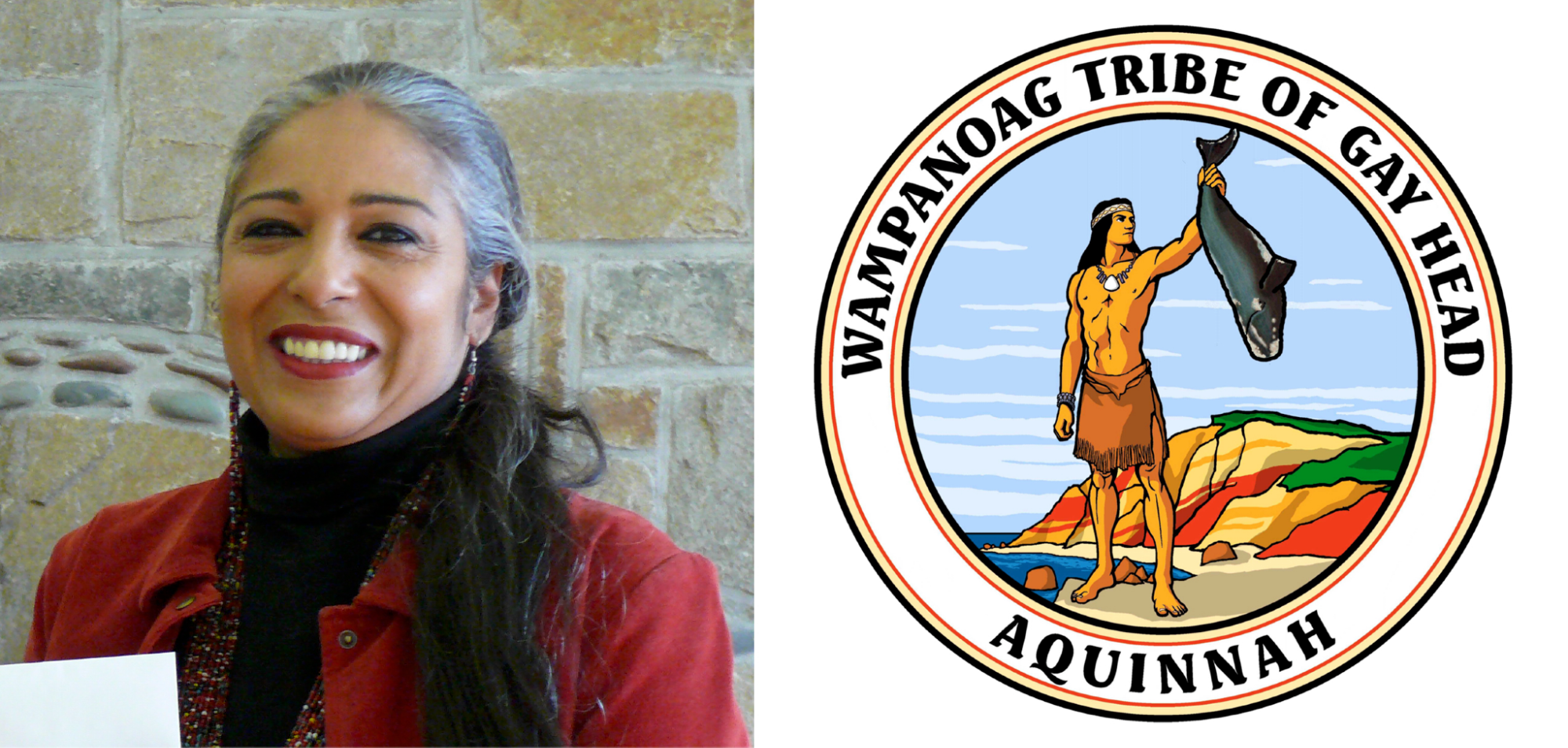

The increased respect for TEK in government reflects a couple of ways we are redefining our notion of health, safety, and security as a society. One, there is growing acknowledgement of the relationship between our environmental crisis and colonial worldviews and practices. During White House consultations with Tribes, Chairwoman Cheryl Andrews-Maltais of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) (figure 7.30) shared:

Had our traditional cultural practices and ceremony not been outlawed and had our information keepers been listened to over the centuries, we probably would not find ourselves in the position we are today—with the losses and extinction and contamination we face as our global community. This is a valuable component of being able to face not only climate change but the preservation and protection of all of our resources (Daniel et al. 2022).

With climate change, our health, safety, and security are increasingly related to our vulnerability in our changing environment. Redefining health, safety, and security in this context means having a deeper understanding of living systems and humans’ impact on their balance.

Two, if redefining public safety involves providing care for peoples’ basic needs—especially those who are in crisis or vulnerable—it is important to acknowledge that our environmental crisis is creating disproportionate hardship for the poor, Indigenous, and people of color.

Decolonization of Health

In this chapter’s Colonized vs. Indigenous Worldviews section, we noted some priorities of an Indigenous worldview on health: 1) taking responsibility for your own health and wellness, 2) knowing traditions, culture, and medicine, and 3) acknowledging that land is what sustains us physically, emotionally, spiritually, and mentally. The increased respect for TEK in society means more people have access to this perspective. It also reflects ways that health is becoming decolonized.

At the same time, there is a resurgence of traditional medicinal practices in Indigenous communities in the United States. For example, the Public Broadcasting System introduced the story of how Indigenous Peoples in California are practicing herbalism with traditional gathering and processing practices to provide for all of their food and medicinal needs.

Watch the 11:35-minute video “Gathering Medicine | Tending the Wild” [Streaming Video] (figure 7.31). It describes TEK in relation to health, and it shows some of the ecological knowledge that members of Indigenous Nations in California keep and apply. As you watch, consider: What do the people in the video consider important for healthy living?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbbcok8Lzs0

In order to provide good health, safety, and security for our communities as climate change advances, it is essential that we better understand the world and include Indigenous knowledge for our well-being. Scientists, environmentalists, and activists are turning to TEK for better ways of living with and managing ecosystems. Many Indigenous communities continue to live close to the Earth, understanding how to act within Earth’s systems for survival. In Chapters 3 and 8, we referred to Indigenous knowledge in the context of decolonization. That is, as we decolonize embedded practices and worldviews, the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples have room to be more valued in society.

Licenses and Attributions for Alternative and Decolonizing Models for Health, Safety, and Security

Open Content, Original

“Alternative and Decolonizing Models for Health, Safety, and Security” by Avery Temple and Aimee Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Decolonization of Policing” includes content from the “Introduction” by Muhammad Asadullah, and from “Decolonization and Policing” by Stephanie Dyck in Decolonization and Justice: An Introductory Overview by Muhammad Asadullah; Charmine Cortez; Geena Holding; Hamza Said; Jenna Smith; Kayla Schick; Kudzai Mudyara; Megan Korchak; Nicola Kimber; Noor Shawush; and Stephanie Dyck, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Aimee Samara Krouskop are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and include content reframed to add reform language and to apply to U.S. law enforcement systems, and added image.

“Universal and Accessible Healthcare” includes adapted content from “19.4 Comparative Health and Medicine” in Introduction to Sociology, 3e.

Figure 7.20. Aneurin Bevan with nurses and a patient at Park Hospital on Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 7.21. “Women of the Black Panther Party” is on Flickr and licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 (left).

Figure 7.23. “Occupy Medical” on Wikimedia Commons, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 7.26. “‘Defund the Police’ projections at a Seattle protest” is on Flickr and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 7.29. Press release “White House Releases First-of-a-Kind Indigenous Knowledge Guidance for Federal Agencies” is published on the U.S. White House website and included under public domain.

Figure 7.30. Chairwoman Cheryl Andrews-Maltais of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) is on Flickr and in the public domain (left).

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 7.21. “The Black Panther Party’s Franklin Lynch Peoples’ Free Health Center in Boston, ca. 1970” is published in the article, Black Panther Party’s Free Medical Clinics (1969-1975) by Diane Pien and included under fair use (right).

Figure 7.22. “The Black Panthers’ Overlooked Health Programs” by TIME is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.24. “Stop Line 5/Stop Line 3” by Keri Pickett is published in the “Tribes, activists from across U.S. gather up north in solidarity of Line 5 + LINE 3 fight” article by Laina G. Stebbins, on the Stop Line 3 website and included under fair use.

Figure 7.25. Qalipu First Nation Pre-Cadet Training Program with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police published by Qalipu First Nation is included under fair use.

Figure 7.27. The Facebook banner of Critical Resistance is posted on the “Critical Resistance” Facebook page and included under fair use.

Figure 7.28. “What Is Transformative Justice?” by Barnard Center for Research on Women is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.30. The logo of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head is found on the Tribe web site and included under fair use (right).

Figure 7.31. “Gathering Medicine | Tending the Wild” by KCET is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the system of norms, rules, and organizations established to provide medical services.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

"the mechanism that will allow for restoration and conciliation of colonized groups who have had their power stolen."

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a healthcare system that is owned and run by the government

a system that guarantees healthcare coverage for everyone.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

mobilization of large numbers of people that seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

figures, extents, or amounts of phenomena that we are investigating.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

a political framework and approach for responding to violence, harm, and abuse. It seeks to respond to violence through harm reduction, or without creating more violence.

a community-based strategy, rather than a police/prison-based strategy, to address violence within communities.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.