8.2 Chapter Story

CULTURAL RESTORATION AND THE WISDOM OF INDIGENOUS-DESIGNED LEARNING

In southwest Colombia, members of the Indigenous Inga Tribe are creating a university with the intention of radical social and ecological transformation. Panamazonic Biocultural Pluriversity AWAI is located in the Putumayo region, where the Amazon and Andes meet. It centers on teaching Indigenous traditional knowledge and aims to address solutions to challenges the Inga people experience. While the university conveys the Inga way of life to their youth, it is also a model that values knowledge from multiple cultural sources. The term “Pluriversity” distinguishes it from colonialist models of education that teach cultural supremacy (the idea that some cultures are more advanced or more valuable than others).

Of great importance to the organizers is teaching how to best preserve their culture and how to best protect and nurture the biodiversity of their territories (figures 8.1 and 8.2). To the Inga people, raising awareness of the interconnectedness between human lives and biodiversity is key to this protection. The Pluriversity is also a model of education that incorporates the values of sumak kawsay, Buen Vivir, and “good living” we learned about. In this way, it is part of a larger social movement.

Hernando Chindoy, a leader of the Inga community, has taken a lead role in creating the Pluriversity. Watch this six-minute interview: “Hernando Chindoy – Two Questions” (figure 8.3) to hear why he believes an Indigenous university is important and some guiding values that inform the project. As you watch, consider what Hernando means by “we learn and reproduce that which is not ours.” Consider what he means by the “imposed layers” that need to be dismantled or transformed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1FT-7TCX3pk

Hernando shares that the project will “reaffirm” their community “as Inga,” in great part by amplifying the use of their language. (Optional: Read more about the Inga Tribe (Spanish Language) [Website].) They also hope to “educate a new generation of Indigenous youth to be prepared for a professional future in their territories and beyond.” It’s a powerful example of cognitive justice, the right for different traditions of knowledge to coexist (Devenir Universidad 2021).

Education in Bolivia: A Very Brief History

Projects similar to Panamazonic Biocultural Pluriversity AWAI have emerged in South America over the last several decades. But they are the fruit of considerable resistance and organizing by Indigenous communities over generations. While the experiences are similar across the continent, let’s look to Bolivia’s story to better understand this history.

When colonizers from Spain arrived in South America, they insisted on teaching the Spanish language and customs. They set up schools led by Catholic missionary priests and brothers, putting pressure on local families to assimilate (Gertostado n.d.). In Bolivia, early colonial education was mostly reserved for the wealthy. However, missionaries would teach Indigenous groups enough language to convert them (Hudson et al. 1991).

In the 1900s, Indigenous communities organized underground schools to educate their children with freedom and autonomy (Jiménez Quispe 2011). As Spanish rule continued to take hold, restricting education was one method of restricting access to power. Then, in the early 1950s, during a national revolution and despite resistance from wealthy landowners, the Bolivian government mandated universal education.

Part of the goal of this government-led education was to separate Indigenous people from their cultural practices. Spanish continued to be required. And practices considered “superstitions” were replaced by more “scientific” education. This was an education that put local Indigenous culture at risk (Contreras 1999).

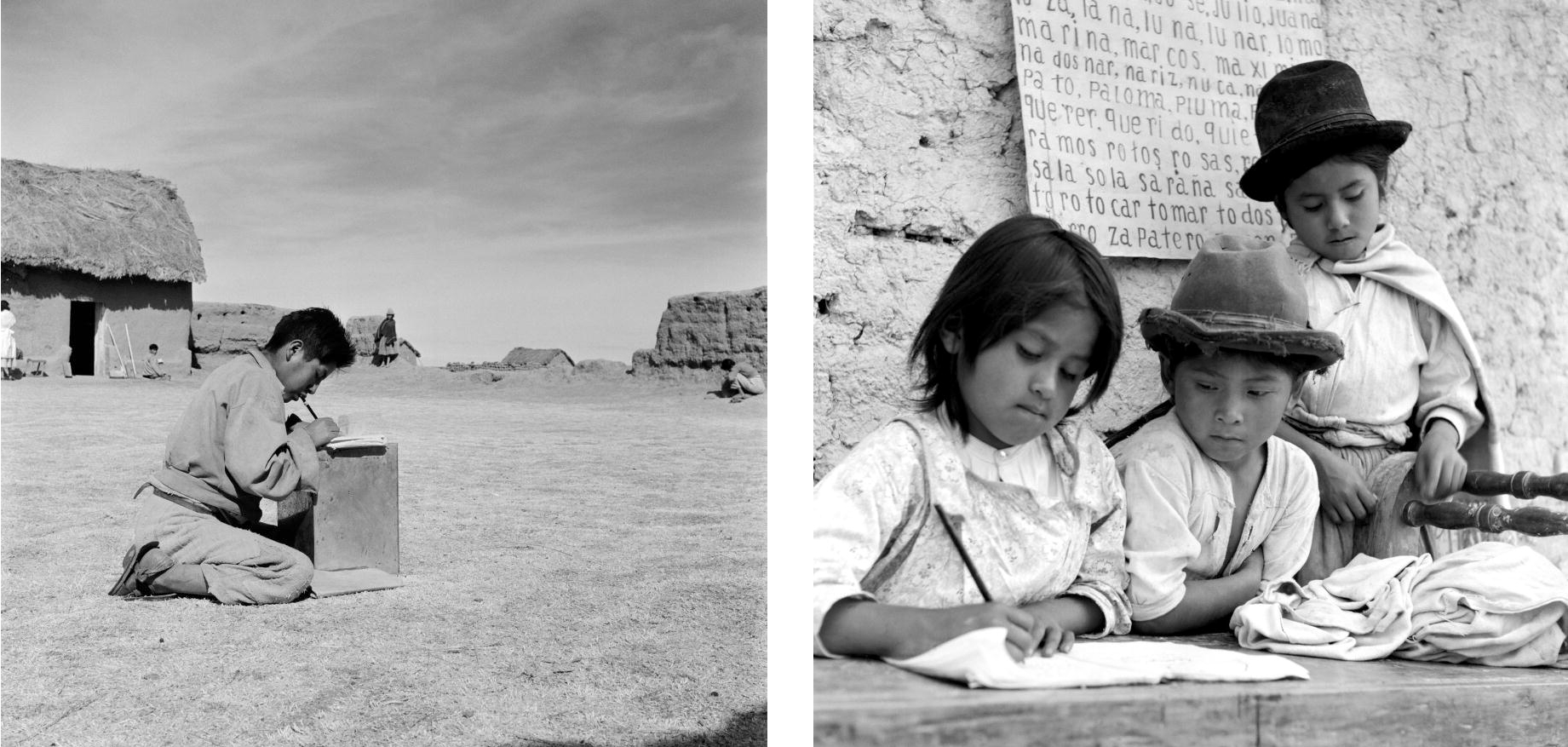

Despite this “castellanización,” the turning of a society’s language and culture into Spanish form, nationalized education had become crucial for survival in Bolivian society. So many Indigenous communities in Bolivia welcomed the opportunity to send their children to school to learn to read and write in a “modern” Bolivia (figure 8.4).

However, many Indigenous students in this era applied their education to advance the Indigenous movement (Jiménez Quispe 2011). This included their right to education based on their own cultural practices. For example, this statement was written by students in 1973:

Excerpt from the Tiwanaku Manifesto

We, Quechua and Aymara farmers…feel economically exploited and culturally and politically oppressed. In Bolivia there has not been an integration of cultures but rather only a layering and domination, maintaining us in the lowest and most exploited stratum in the social pyramid.

The education [we receive] not only seeks to convert the Indian into a species of mixed person without definition or personality, but it also pursues his assimilation into the western and capitalist culture (Jiménez Quispe 2011 in Rivera Cusicanqui 1986).

Policy and Indigenous Autonomy

This legacy of resistance to colonial education continued in Bolivia. Indigenous education projects began to prioritize Indigenous knowledge. These changes came hand in hand with increasing human rights violations against Indigenous Peoples in Bolivia. Because they live on land that armed groups often want to control, Indigenous lives became particularly at risk (figure 8.5).

Indigenous education projects also began to incorporate Western education to prepare students to make change for their communities from within Western institutions. Eventually, Indigenous leaders found their way to spaces of power, such as the government, where they began to win policy changes that better served their communities.

Bolivia’s Constitution of 2009 was a significant achievement for education. It recognized the country as a plurinational state. That is, it acknowledged the country is made up of many Indigenous Tribes with their own languages and customs. It dictates that, in addition to Spanish, education must be provided in the Indigenous languages of students (The Constitute Project n.d.).

Equally important are the Constitution’s articles that uphold Indigenous autonomy, acknowledging Indigenous Peoples’ rights to decide how to educate their children. Education is an agent of social change. When communities and students question authority to fight for the kind of education they need, education can be a force for social justice.

In this chapter, we’ll explore how education can be used as a tool to reinforce inequality historically, currently, and worldwide. We’ll also examine how education serves as a medium for resistance against that inequality. It will encourage you to ask questions about how education, as a conveyor of culture, influences your life experiences and the experiences of others.

- How does our access to certain cultural practices and knowledge play a role in educational inequality?

- How can education be a vehicle to impose a culture upon another society and advance cultural genocide?

- How can education support social justice and cultural restoration?

Going Deeper

For more information on the Indigenous University (Panamazonic Biocultural Pluriversity AWAIP), watch more of the video with Hernando: “Hernando Chindoy – Indigenous University” [Streaming Video] (starting with 6:02). Also, see the website of Devenir Universidad, the Swiss project that is partnering with the Inga organizers.

For a snapshot of the state of Bolivia’s education system today, watch “Indigenous Bolivians Learn to Read and Write” [Streaming Video].

Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Story

Open Content, Original

“Chapter Story” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.1. “A Graffiti Wall in Mocoa, Putumayo” by Ocean Malandra is published on Mongabay and licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.

Figure 8.2. “Boy and Farm” is on Flickr, by KyleEJohnson, and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.4. “Combined Effort Aids Indigenous Population in Bolivia” is on Flickr by United Nations Photo and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (left). “Sharing Skills” by United Nations Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (right).

Figure 8.5. “Misión de Monitoreo Final Proyecto” by Ocha Colombia is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (left). “Escuela Mixta Indígena” by Mauricio Romero Mendoza is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (right).

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.3. “Hernando Chindoy-Two Questions” is an excerpt of “Hernando Chindoy – Indigenous University” created by Ursula Biemann at Devenir Universidad. The excerpt is hosted on the Open Oregon Educational Resources YouTube page, and included with permission.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

a set of ethics that balance quality of life, democracy, giving inherent value to all living things, and collective well-being.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a state where "everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life.”

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.