8.5 Genocide and Cultural Restoration

The institution of education is a powerful influence on the lives of members of society. One reason it is so powerful is that it teaches cultural norms and expression to young people as they are in their developmental stages. Education can help unify societies when it gives young people a chance to learn and practice their shared culture. Educational systems can also be a vehicle for violence, oppression, and the breakdown of societies through access to and control of young people.

The establishment of boarding schools for Indigenous children in the 1800s and 1900s was one part of the U.S. government’s history of genocide, which we defined in Chapter 1 as the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

In this section, we’ll look at the history of American Indian boarding schools (also known as Indian residential schools) in the United States. We’ll also look at how Tribal nations are exercising cultural resilience and recovery from this history. They are using education to fight back against oppressive policies of the past, reclaim their sovereignty, and restore the widespread practice of their ways of life.

Indian Residential Schools

In 2021, Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo, was sworn in as the first Native American Secretary of the Interior (figure 8.28). (Optional: Read more about the Laguna Pueblo [Website].) After her confirmation, she immediately launched a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. In her role as secretary, and as a Native American, she was uniquely positioned to introduce the history of the schools to the wider public:

Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate [I]ndigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of [I]ndigenous children were taken from their communities (Haaland 2021b).

The investigation reported that tragically, many children died while in the schools—a restatement of what many survivors of the schools have known (Beaumont 2021).

The report documents that at least 500 children were buried in 53 burial sites on residential school properties (Newland 2022). “The Department expects that continued investigation will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands” (Newland 2022, p. 93).

Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children died while in Canadian residential schools, which were run similarly to those in the United States (Montoya Bryan 2021). (Optional: Read more about First Nations, Inuit, and Métis [Website].)

The boarding schools were government-funded and often operated by churches. They were part of a three-pronged land acquisition strategy to make way for the expansion of the United States. First, that strategy included reorienting the practices of Indigenous Peoples so they could be forced to exist in smaller geographical areas. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous Peoples would make land available for colonists:

To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts (Jefferson 1803 in Newland 2022:21).

The boarding school system coincided with the direct removal of many Tribes from their ancestral lands. This is a concrete example of land grabbing, a practice you learned about in Chapter 4.

Second, that strategy included the disruption of the social fabric of Indigenous Peoples through the separation of families. Government records written at the time read, “If it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022:38). Sometimes their parents wrote letters asking for their children to be returned. Sometimes the children tried to run away (Hiruko 2023).

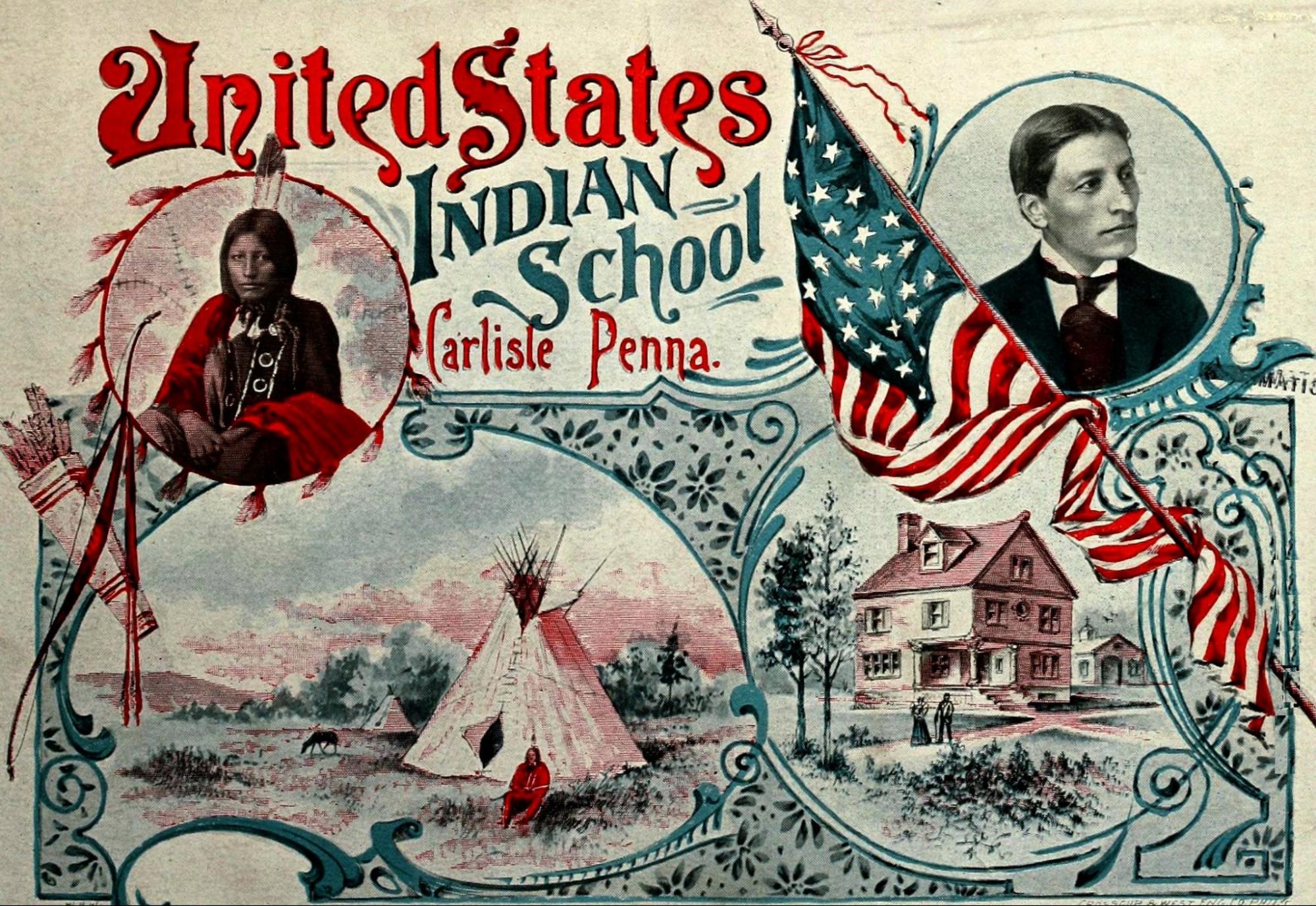

Third, that strategy included the disruption of the culture and belief systems of Indigenous societies. Secretary Haaland recounted the suffering in her own family: “My great-grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. The school’s founder coined the phrase ‘kill the Indian and save the man,’ which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021a).

The Indian schools stripped Native American children of their cultural heritage and indoctrinated them with the cultural values of white U.S. society (Newland 2022) (figure 8.29). This was a practice of cultural hegemony: “the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who shapes the culture of that society…so that the worldview of the ruling class becomes the accepted cultural norm” (Bullock et al. 1999).

Upon their arrival, Native children were given Anglo-American names and military-style clothing. Their hair would be drastically cut, as authors at The New York Times described: “A particularly cruel and traumatic step for those coming from cultures like the Lakota, where the severing of long hair could be associated with mourning the dead” (Levitt et al. 2023).

Students were required to learn English, agriculture, math, history, and trades that would make them marketable in U.S. society. Education emphasized U.S. values such as the concepts of private property and wealth through material possessions. Students were also forced to convert to Christianity. Boarding school staff punished them if they spoke their Indigenous languages or practiced their own spiritual practices. Lack of food, corporal punishment, sexual abuse, and shaming were all used to force children to conform (King 2008).

This system that required stolen Native children to adopt a different culture and belief system than their own was a form of forced cultural assimilation: a process by which a community with a dominant culture forces members of other groups to adopt their language, national identity, norms, customs, values, ideology, and way of life. Their food, shelter, and their avoidance of abuse hinge on their cooperation.

Take a moment to look at the photos taken at the Forest Grove Indian Training School in 1881 (figures 8.30 and 8.31).

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos, noting that the first photo (figure 8.30) is of new arrivals from the Spokane Tribe. The second photo of the group (figure 8.31) is dated seven months later. “In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck” (Francis 2019). Sadly, one girl is missing in the second photo. Martha Lot was about 10 years old, and historical records only indicate she suffered “a sore” on her side before passing away. Mike Francis reflects:

The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad—frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of [I]ndigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures (Francis 2019).

With this forced cultural assimilation, government leaders and missionaries produced a spiritual and emotional breaking of young people and an assault on their sense of Tribal identity. Alongside the separation of families and removal of Tribes from their ancestral lands, there was a severe rupture of previously intact communities.

Healing Generational Harm

The last American Indian boarding school closed in 1983 (Wertheimer et al. 2022). Like others, it was demolished (in 2007), to the relief of many former students and their families. However, as survivor Regina Gasco-Bentley shares, “…there’s part of it still there and there’s still a lot of memories. It’s right in the middle of our homelands and there’s people that have not been able to heal from the abuse they took in the school” (Ware 2022).

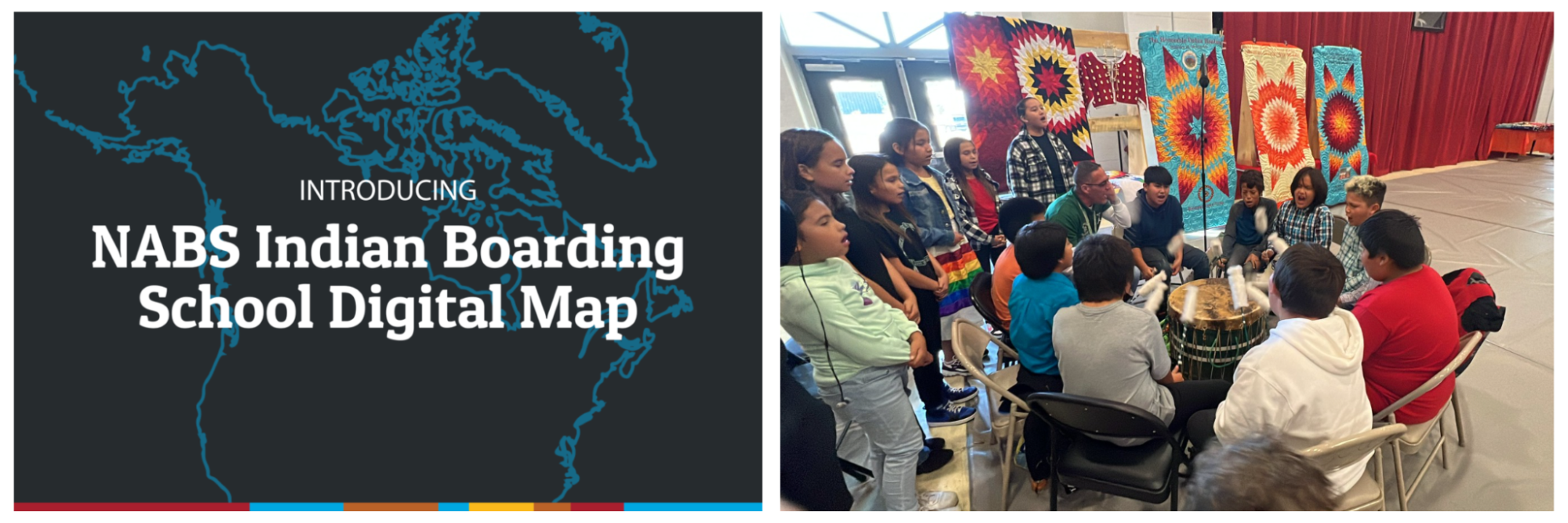

While there is much more to be done, there are recent efforts that acknowledge the horrors of the residential schools and offer to support the healing of survivors. For example, the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition was formed in 2011 to advocate on behalf of Native peoples impacted by American Indian boarding school policies. Among other goals, they focus on revealing the truth of the residential school system through research and education and providing opportunities for healing through programs and traditional gatherings. In 2023, they launched a database that allows Native Americans to search for information on relatives who attended American Indian boarding schools and an interactive digital map of American Indian boarding schools (figure 8.32).

Another example of working to repair generational harm occurred in 2022, under Secretary Haaland’s leadership, when U.S. Department of the Interior officials commenced a Road to Healing tour. It was a year-long initiative that invited former boarding school students from Native American Tribes, Alaskan Native villages, and Native Hawaiian communities to share their stories as part of a permanent oral history collection.

Secretary Haaland shared, “It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal American Indian boarding school policies but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous Peoples can continue to grow and heal” (Fonseca 2022). With both of these initiatives, education is being applied to heal generational harm.

An obvious question emerges as the United States begins to grapple with its residential school history: How well does the education system in the United States serve Native Americans today? Researchers point to the fact that Indigenous students have the lowest educational attainment of any group in the United States (Martinez 2014). This is in great part due to limited access. But it’s also no wonder, considering the kidnapping, violence, forced assimilation, and abuse that Native Americans have experienced in the U.S. educational system.

It’s important to think critically about the negative value overall that a U.S. model of education would hold for many Native Americans due to this history. It also remains that credentials and a certain degree of formal education are important to navigate and survive in U.S. society. How can this be reconciled?

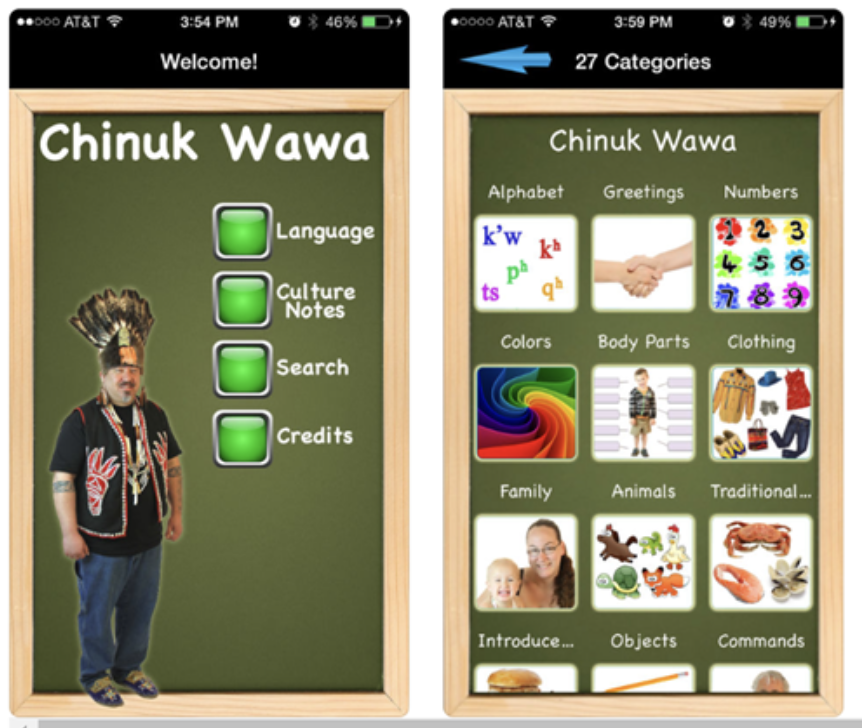

One important way is through language. As mentioned earlier, one of the strategies for forcibly assimilating Indigenous children at the boarding schools was to forbid them from speaking their own languages. There is a movement underway in the United States to weave Indigenous languages into school offerings. The Native American Languages Act was passed in 1990. It established a federal policy to allow the use of Native American languages for instruction in schools. It also affirmed the right of Native American children to express themselves, be educated, and be assessed in their own Native language.

Oregon Tribes were provided funding to develop curricula specific to their culture and location. For example, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde developed a curriculum for fourth graders that teaches students about Chinuk Wawa, the trade language used by many Tribes who lived up and down the Pacific coast. Students may learn in an app if they choose, and the language is becoming revitalized for the entire community (figure 8.33).

Language is important to families and communities because it serves as the vehicle for cultural expression and heritage. Languages often convey knowledge about life and the natural world known by communities that can only be expressed in their own tongue.

Incorporating language and culture into educational offerings is also important to creating equity. Dorothy Lazore, who teaches immersion Mohawk, observes: “For Native people, after so much pain and tragedy connected with their experience of school, we finally now see Native children, their teachers and their families, happy and engaged in the joy of learning and growing and being themselves in the immersion setting” (Lazore as cited in Johansen 2004:569).

Scholars at the Bureau of Indian Affairs write:

…Language revitalization is a core aspect of cultural continuity, protecting traditional knowledge and practices, and resisting assimilation.…revitalization efforts increase the visibility and prestige of Indigenous culture and can be used deliberately and strategically by speakers to combat cultural and linguistic hegemony (Bureau of Indian Affairs 2023:24).

Watch the 4.53-minute video “Boarding School Healing Voices [Streaming Video]” (figure 8.34) to hear from Elder survivors about their experiences. As you do, consider: Why is educating people about the boarding schools important to them?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjUto-mQrfQ

The genocide of people and culture that occurred as colonists established Indian residential schools created wounds that remain unhealed today. At the same time, Indigenous people are reclaiming the bones of their children, their languages and ceremonies, and sometimes the spaces where schools stood themselves.

Going Deeper

For more information on the history of genocide in the United States, read “Genocide and American Indian History” [Website].

For more on Indian boarding schools:

- Read sections written by authors of this chapter in Chapter 5 and Chapter 14 of Contemporary Families [Textbook].

- See the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report [Website] mentioned in this chapter.

- Watch “How the U.S. Stole Thousands of Native American Children” [Streaming Video], “Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools” [Streaming Video], and “The Forest Grove Indian Training School, 1880–1885” [Streaming Video].

Read more about the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition [Website] advocacy on behalf of Native peoples impacted by American Indian boarding school policies.

Licenses and Attributions for Genocide and Cultural Restoration

Open Content, Original

“Genocide and Cultural Restoration” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Indian Residential Schools” by Kimberly Puttman in “Violence and Oppression: Indian Residential Schools” in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adapted to focus on social change.

Figure 8.28. Deb Haaland, sworn in as U.S. Secretary of the Interior is on Flickr, by U.S. Department of the Interior and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (left). Deb Haaland, portrait is on Wikipedia and in the public domain (right).

Figure 8.29. “Commemorative booklet of the United States Indian School” is on Flickr, by Midnight Believer and in the public domain.

“Healing Generational Harm” includes content from “Healing Generational Harm” in Contemporary Families by Aimee Samara Krouskop.

Figure 8.32. “Road to Healing South Dakota” is on Flickr, by the U.S. Department of the Interior and in the public domain (right).

Figure 8.33. Screenshot of the “Chinuk Wawa Book and App Image” by the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde is in the public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.30. “Image” from A Tragic Collision of Cultures is in the public domain. Courtesy of Pacific University Archives. Caption by Mike Francis is included under fair use.

Figure 8.31. “Image” from A Tragic Collision of Cultures. Courtesy of Pacific University Archives. Caption by Mike Francis is included under fair use.

Figure 8.32. “Screenshot of NABS Indian Boarding School Digital Map” by National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition is included under fair use (left).

Figure 8.34. “Boarding School Healing Voices” by Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

"dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class that shapes the culture of that society …so that the worldview of the ruling class becomes the accepted cultural norm."

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

a process by which a community with a dominant culture forces members of other groups to adopt their language, national identity, norms, customs, values, ideology, and way of life.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.