8.6 Teaching That Transforms

Improving access to education through policy, bringing residential school survivor voices to the forefront, and restoring culture through language are all strategies that help change the institution of education so it works for everyone. Teaching itself also has the potential to transform when administrators and instructors listen to students (and former students) as they relay what they need. This section will look at some ways teaching approaches are changing to improve equity in education.

Community Cultural Wealth

One way of advancing equity in education involves examining our assumptions about what is valuable for success in life—that is, examining how we socially construct the resources we believe are needed to do well in school, care for ourselves and others, or thrive in society. Earlier in this chapter, we discussed how educational opportunities are unevenly offered in U.S. society due to differences in cultural capital. Through a social construction lens, we can see that the cultural capital valued in that framework is that of the dominant society.

In 2005, Dr. Tara Yosso introduced a different way of seeing and thinking about resources. Community cultural wealth is the “interdependent overlapping forms of knowledge, skills, abilities, and networks possessed and utilized by communities of color to survive and resist racism and other forms of subordination” (Yosso 2023). For individuals, this is the personal and community resources they have beyond their income or accumulated financial wealth. Often, they include skills such as resilience and social networks developed from navigating or resisting social bias and inequities.

As she presented the concept of community cultural wealth, Yosso critiqued the common idea that youth of color need to be taught dominant forms of “cultural capital.” Instead, she illustrated how they are already rich in various cultural wealth.

One component of community cultural wealth is familial capital. Yosso writes:

…Familial capital is nurtured by our “extended family,” which may include immediate family (living or long passed on) as well as aunts, uncles, grandparents, and friends who we might consider part of our familia. From these kinship ties, we learn the importance of maintaining a healthy connection to our community and its resources. Our kin also model lessons of caring, coping and providing (educación), which inform our emotional, moral, educational and occupational consciousness (Yosso 2005:79).

The family itself can help students succeed in school, and it can serve as a source of power for people of color to resist white supremacy and thrive despite economic and social inequality. Take a few minutes to look at the Cultural Wealth Wheel in figure 8.35. It’s an adaptation from Yosso’s model, but it describes the six specific types of cultural capital she introduced. In what area is your strongest cultural wealth?

Yosso’s model asks school administration and instructors to consider less how a person’s race, ethnicity, or class might lead them to have less cultural capital than white and middle- to upper-class students. Instead, she encourages them to focus on the wealth of cultural capital that is often unacknowledged and undervalued. When educators are able to make this shift in perspective, they can better serve students, and they can better serve a larger purpose of struggle toward social and racial justice.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Paulo Freire (1921–1997; figure 8.36) was a sociologist, activist, and educator in Brazil and internationally from 1940 to his death in 1997. He founded and ran adult literacy programs in the slums of northeast Brazil. When he taught reading and writing, he used everyday words and concepts that his students needed to know to live well, like terms for cooking, childcare, or construction. More revolutionary, though, was his idea that education could also be a force for liberation.

He believed that students and teachers could ask questions together about why things were the way they were in society. By arguing that the teacher was also a learner and that students were also teachers, he created classrooms in which students could feed their own curiosity and come to their own conclusions. Freire explored the practice of pedagogy: the art, science, or profession of teaching.

His most famous book is Pedagogy of the Oppressed. There, he condemns the banking model of education, which he defines as “the concept of education in which knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (Freire 1970). He argues that the banking model of knowledge is the most common but least useful form of education. He writes:

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat…but in the last analysis, it is the people themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system (Freire 1970:72).

As a response, Freire’s model of education emphasizes dialogue, action, and reflection. Each person contributes from their own experience and knowledge. This combination of engaging in the world and then reflecting on what you learned, or praxis, is the true goal of education. He writes, “It is not enough for people to come together in dialogue in order to gain knowledge of their social reality. They must act together upon their environment in order critically to reflect upon their reality and so transform it through further action and critical reflection” (Freire 1970). Freire’s institute still influences educators and thinkers worldwide about how to use education to promote social justice.

Black Liberation

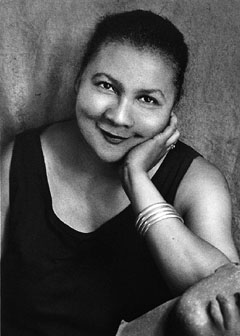

Author and educator bell hooks (1952–2021; figure 8.37) used lowercase letters for her name to encourage more focus on her works than her personal qualities (Alhumaid 2019). She joins the work of Paulo Freire and feminist theorists to expand on ways that education can transform society, specifically for Black liberation and for Black women. In her book, Teaching to Transgress, she writes:

Almost all our teachers at Booker T. Washington were black women. They were committed to nurturing intellect so that we could become scholars, thinkers, and cultural workers—black folks who used our “minds.” We learned early that our devotion to learning, to a life of the mind, was a counter-hegemonic act, a fundamental way to resist every strategy of white racist colonization. Though they did not define or articulate these practices in theoretical terms, my teachers were enacting a revolutionary pedagogy of resistance that was profoundly anticolonial.

For black folks teaching—educating—was fundamentally political because it was rooted in antiracist struggle. Indeed, my all-black grade schools became the location where I experienced learning as revolution (hooks 1994:2).

Hooks names the classroom itself as a space of resistance and a place to create social justice. She takes an intersectional lens to describe how Black women have unique experiences of inequality in society. Through feminist critical education, they can challenge the ideas of white women who define their experience as universal. They can challenge the ideas of Black men, who also universalize their experiences as Black. She writes:

I am deeply committed to black liberation struggle and want to play a major role in re-articulating the theoretical politics of this movement so that the issue of gender will be addressed, and feminist struggle to end sexism will be considered a necessary component of our revolutionary agenda (hooks 1992:112).

Not only does Black liberation need to include issues of gender, but feminism needs to include issues of race and ethnicity. From this perspective, she encourages engaged pedagogy, a style of teaching and learning that combines personal experience and academic learning to think critically about the world and act to change society. Education itself must be revolutionary in its approach and its outcomes. Like Freire, she argues that a classroom is a community. Social justice occurs within a community of engaged learners when they act to change the world.

Culturally Responsive Education

Culturally responsive education is another framework that educators are applying to better serve a diversity of students. Professor Gloria Ladson-Billings introduced the term in the mid-1990s, describing it as “a pedagogy that empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (Ladson-Billings 1994:382). With this methodology, teachers make content and curricula accessible to students and teach in a way that students can better understand in the context of their lives.

A star in this field is Chris Emdin, a professor at Columbia University’s Teachers’ College. He challenges educators to embrace and respect each student’s culture and to use culturally relevant strategies. In his own teaching of science, he applies hip-hop music and call-and-response to connect to the experiences of urban youth.

Watch the 2:14-minute video in figure 8.38, “Dr. Christopher Emdin: Hip Hop Ed in the Classroom.” It highlights the culturally responsive methods of Professor Emdin and how he weaves hip-hop into his curriculum. As you do, consider: Why are his methods effective for the students present in the video?

Decolonization and Indigenization

Another perspective and set of tools for social transformation within schools is decolonization and indigenization (sometimes called re-indigenization). They work together to acknowledge and begin the long process of healing the effects of colonization, including systematic, extended effects like the intergenerational damage of residential schools.

Decolonization of knowledge is the process of examining and undoing colonial ideologies that frame Western thought and practices as superior. A topic in academia since the 1970s, a significant contribution came from Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano (1928–2018; figure 8.39). Quijano explored coloniality and power and argued that if knowledge is colonized, then one of the most important tasks ahead is to find ways of decolonizing that knowledge (Quijano 2000).

Decolonization of education is the process of confronting and challenging the colonizing practices that have influenced education in the past and which are still present today. It is an approach that recognizes how worldviews rooted in colonization, in and out of the classroom, perpetuate systems of inequity, violence, and separation. It also involves valuing and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge and approaches, and weeding out Western biases or assumptions that have impacted Indigenous ways of being.

Non-Indigenous educators who practice decolonization acknowledge different ways of knowing and examine the knowledge they hold and how they acquired it (Antoine et al. 2018). They will include scholars or knowledge keepers in their curriculum who have been overlooked. They will try to reflect broader global and historical perspectives. The decolonizing approach also reflects carefully on the goal of education, often revealing that the motives of mandated, state-sponsored education are rooted in colonialist policy (Centre for Youth and Society n.d.).

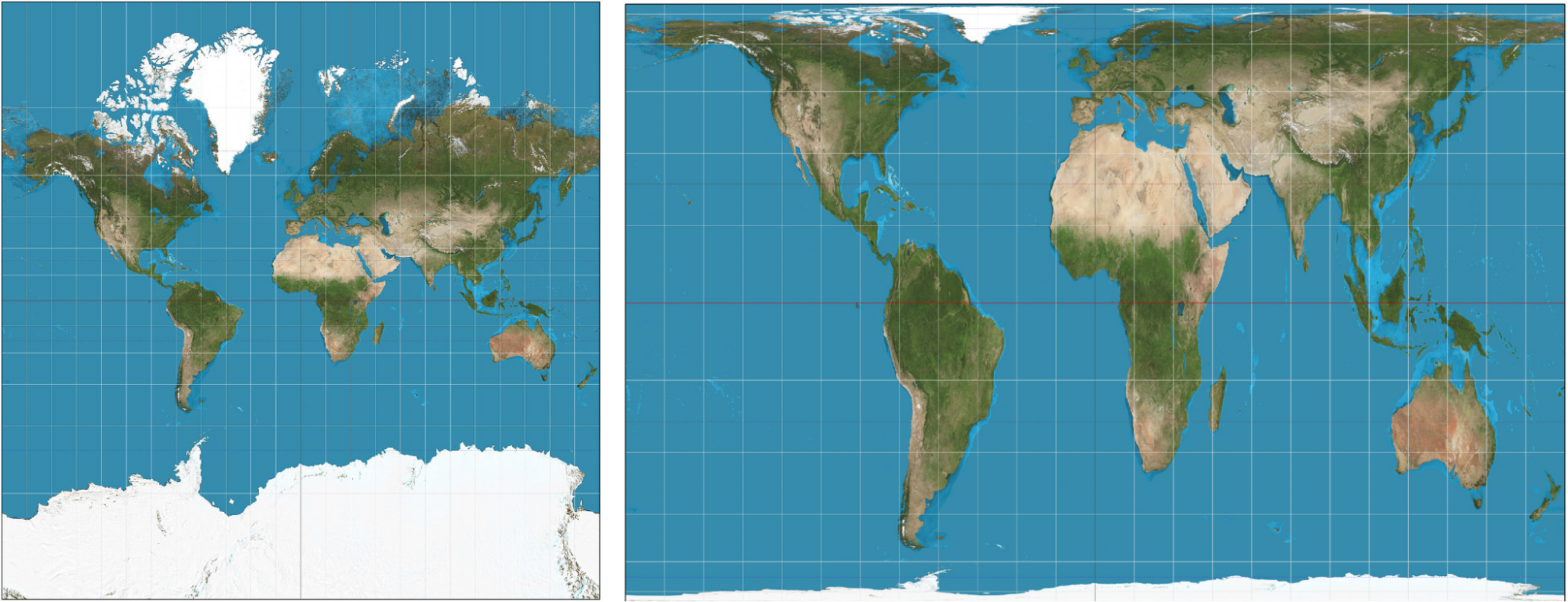

One way to visualize the decolonizing of knowledge is to consider the map of the world most commonly introduced to students: the Mercator projection (figure 8.40). This is how the image of our flattened world has been generally accepted since the 1500s.

As maps are tools that dramatically guide understanding of our social world, they have considerable power. However, this map projection distorts the relative sizes of global regions. It is drawn with parallels of latitude as horizontal lines spaced farther and farther apart as their distance from the Equator increases. This presents landmasses such as Greenland and Russia as far larger than they actually are relative to landmasses near the equator, such as central Africa. It also presents Europe and North America as larger than they are relative to Africa and South America.

Compare the Mercator projection to a map drawn with the Gall-Peters projection (figure 8.41). Africa, South America, and Australia take on a whole new shape as this map represents the sizes of countries in a far more accurate manner. In comparison, we can see how the Mercator projection exaggerates the size of colonizing powers, prioritizing them and reflecting a Eurocentric and North America-centric view of the world.

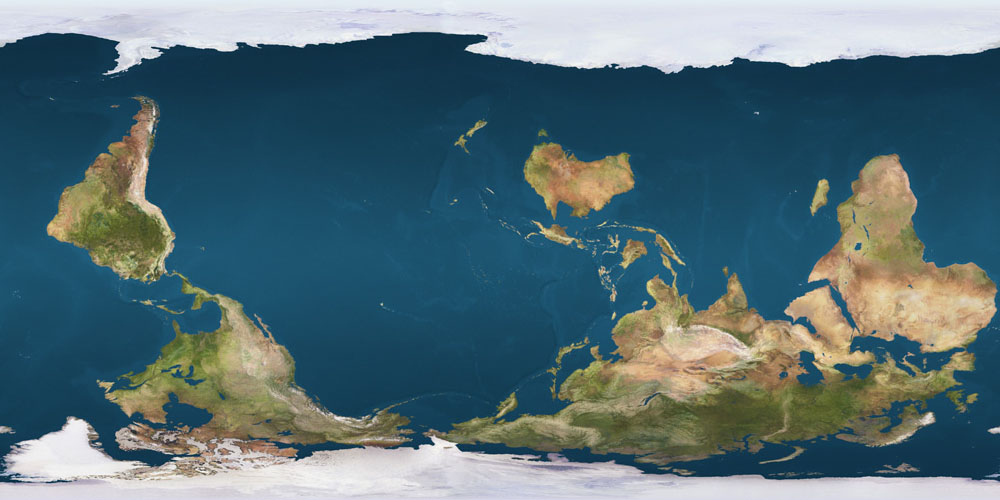

Another way to undo the predominant placing of nations is with inverted maps. Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949), an Uruguayan modernist painter, offered one of the first inverted maps as a political statement in 1900 (De Armendi 2009). The modern and popular McArthur’s Universal Corrective map (figure 8.41) is as accurate as the Gall-Peters projection, but it turns the north-south placement of land masses on their heads. This orientation places colonizing nations at the bottom of the map and the southern hemisphere more centrally.

Making these alternative maps available is a powerful way of decolonizing knowledge in the classroom. Recently, maps based on the Gall-Peters projection have been promoted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). They’ve become widely used in British schools and have been adopted as the standard in the Boston public school system in the United States (Higgins 2009; Walters 2017).

Indigenization is a process of making Indigenous knowledge systems evident, prevalent, and available. In the educational setting, this means recognizing that Indigenous knowledge systems are embedded in a relationship to specific lands, cultures, and communities. So when educators practice indigenization, they will prioritize learning experiences that are place-based and that help Indigenous students access their cultural knowledge. As they do so, other forms of education and knowledge systems are acknowledged, appreciated, and incorporated into the dominant education system.

Community involvement is crucial to this model of education, as it connects students to their support system and allows them to place knowledge in context (Centre for Youth and Society n.d.). Professor Rowena Arshad offers a good example:

…In astronomy when we discuss life, universe, planet and stars, we can open up discussions on how different perspectives might understand these topics. How might different [I]ndigenous communities understand and talk about stars? Would it be in the language of exploration and conquest of space or in terms of navigation and survival? (Arshad 2021)

Elder Albert Marshall from the Eskasoni Mi’kmaw First Nation (2012) describes this approach as etuaptmumk, “two-eyed seeing.” It’s a way to learn to appreciate both Indigenous and Western knowledge and ways of knowing. He contends that by fostering an active engagement with both ways of seeing, we are providing all students (not only Indigenous students) with support systems to move toward a decolonized academy.

Finally, indigenization of education includes addressing the social injustices and racist policies to which Indigenous Peoples have been subjected. The history and current situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and the United States differ in significant ways from that of immigrants and minority settlers. These differences must be acknowledged to form respectful relationships.

Going Deeper

For more reading on cultural capital, read Yosso’s article, “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth” [Website].

To learn more about Paulo Freire, watch “Paulo Freire and the Development of Critical Pedagogy” [Streaming Video]. To listen to Paulo Freire speaking about his work, watch “Conversation with Paulo Freire” [Streaming Video].

To hear more about feminism and critical education theory, watch “bell hooks on Paolo Freire” [Streaming Video]. You can also hear more from bell hooks on violence and race in “bell hooks Interview” [Streaming Video].

For a take on how the television series The West Wing introduced the Mercator projection, Gall-Peters projection, and McArthur’s Universal Corrective map into an episode, watch this scene [Streaming Video].

For more about two-eyed seeing by Elder Albert Marshall, you can read the paper “Two-Eyed Seeing – Elder Albert Marshall’s Guiding Principle for Inter-Cultural Collaboration” [Website].

Licenses and Attributions for Teaching that Transforms

Open Content, Original

“Teaching that Transforms” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Pedagogy of the Oppressed” by Kimberly Puttman from Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adapted to focus on social change.

Indigenization content in “Decolonization and Indigenization” includes content adapted from Indigenization, Decolonization, and Reconciliation and “The Need to Indigenize” in Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers by Asma-na-hi Antoine; Rachel Mason; Roberta Mason; Sophia Palahicky; and Carmen Rodriguez de France is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 8.36. “Painel Paulo Freire” by Luiz Carlos Cappellano is in the public domain (right).

Figure 8.37. “Photo of bell hooks” is on Flickr, by Kevin Andre Elliott and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 8.39. “Aníbal Quijano” is on Wikimedia Commons by Cancillería del Ecuador and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (left).

Figure 8.40. “Mercator Projection Square” is on Wikimedia Commons by Strebe and licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (left). “Gall-Peters Projection SW” by Strebe is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (right).

Figure 8.41. “Reversed Earth Map” is on Wikimedia Commons, by Poulpy is in the public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.35. “Cultural Wealth Wheel” by Alexandria Gurley, UNT Digital Library, is included under fair use.

Figure 8.36. “Brazilian Activist and Educator, Paolo Freire” by FisicalBook is included under fair use (left).

Figure 8.38. “Dr. Christopher Emdin: Hip Hop Ed in the Classroom” by AccuTrain is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 8.39. “Aníbal Quijano Memorial” published on Red Latina sin fronteras by Olver Quijano Valencia is included under fair use (right).

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the cultural knowledge and items that help one navigate a society.

"the interdependent overlapping forms of knowledge, skills, abilities, and networks possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist racism and other forms of subordination"

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the belief, theory, or doctrine that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups, and are therefore rightfully the dominant group in any society.

the unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in societies.

a critical term for a type of education in which “knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (Freire 1970).

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

a state where "everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life.”

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

"a pedagogy that empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes."

a process of making Indigenous knowledge systems evident, prevalent, and available.

the process of examining and undoing colonial ideologies that frame Western thought and practices as superior.

"the mechanism that will allow for restoration and conciliation of colonized groups who have had their power stolen."

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.