9.3 Religion, Spiritual Belief Systems, and Power

Religions help answer questions that hold meaning for societies and communities. They might be, “What does it mean to be a good person?” or “What happens when we die?” Sociologically defined, religion is a communally organized and persistent system of beliefs, values, practices, and relationships concerning what is sacred or spiritually significant. For example, Christianity establishes codes by which members agree to live. It is also an organization that maintains places of worship and spiritual leaders, organizes spiritual education for children, manages wealth, and exerts political influence. We see these same structures repeated across time, place, and culture. Sociologists identify religion as one of the major social institutions we explored in Chapter 2.

Identifying spirituality and how it relates to religion and society is more complicated. It requires us to consider that it is groups in power that evaluate the diverse sets of beliefs and practices in the world. It also requires that we consider the consequences of classifying some beliefs and practices as legitimate and others as not.

Decolonizing “Religion”

In Chapter 1, we introduced the specific process of colonization implemented by France and the Catholic Church in the 19th century. As France colonized Algeria, it incorrectly defined Islam as backward and immoral. As Western Europeans colonized other parts of the world, they used their own concept of religion to similarly dismiss, denigrate, and suppress the spiritual practices of those in the land they were occupying. This was true for other organized religions like Islam and spiritual worldviews held by Indigenous groups.

Islam, like Christianity, has extensive origins. It is a monotheistic faith centered around belief in the one God (Allah) and traces its history back to the biblical patriarchs Abraham and Adam. Indigenous Earth-based spiritualities have sophisticated understandings of the interrelationship between people and the natural world. Nevertheless, European colonists saw their practices as incorrect and simple, believing people who practiced these ways needed to be converted to Christianity in order to be civilized. Religious conversion became a tool of colonialist power. Dr. Sarah J. King, a Canadian religious scholar, writes:

Through the colonial process, as European Christians moved around the world, they struggled to understand the diverse cultures and philosophies they encountered. They brought the category of “religion” with them, to help them order and understand the unfamiliar….

[I]ndigenous ways of life have been recast in Western terms, made into “actual religions,” in order to render them more familiar. Even the use of the word religion to describe the lives of [I]ndigenous people is a part of this process since the category of “religion” arises in Western (and not [I]ndigenous) epistemology (King 2013).

As you prepare to think about religion and social change, consider that the ways religions are acknowledged and approved depend on the people who are in positions of power. For example, the next section will introduce you to the ideas of Émile Durkheim, known for establishing the first formal, independent academic discipline of sociology. Durkheim’s ideas are presented in this text as foundational to how sociologists analyze the role of religion in society. However, Durkheim’s ideas on religion were developed in the context of the 19th-century British settlement of central Australia. They were informed by white supremacist ideas that framed the beliefs of other societies as disorganized and “primitive” in contrast to European religion (Nye 2019).

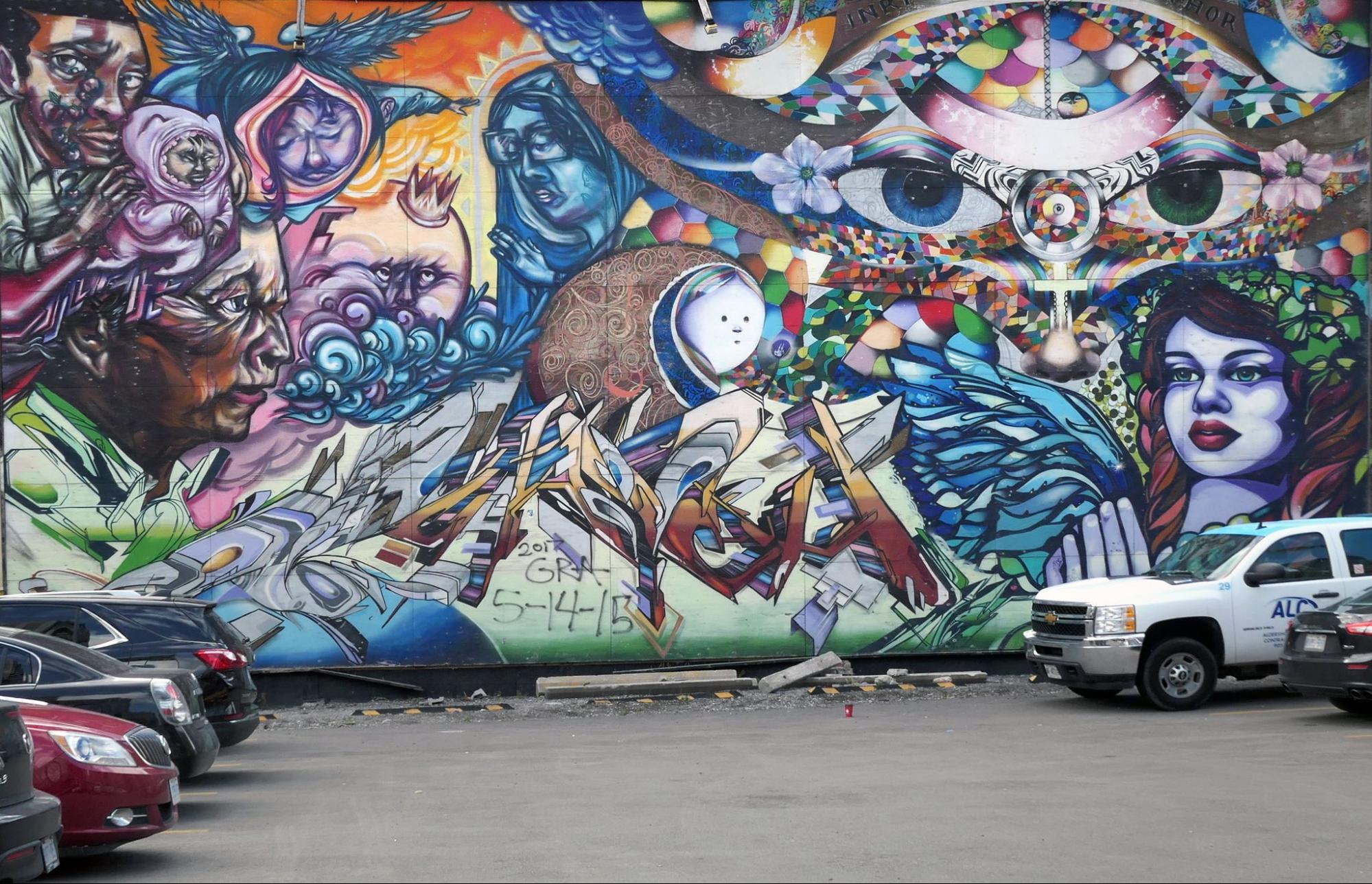

While plenty of religious organizations today recognize the value of other faiths and practices (figure 9.5), many of these supremacist perspectives remain. Therefore, examining religion and social change requires challenging these ideas of correct or incorrect beliefs. It’s important to think critically about how these ideas influenced the treatment of communities that did not practice the endorsed religions of the European world. It is equally important to frame these ideas in the context of power and colonization, as they exist today.

To decolonize our study, we will explore how religion as an institution can be used to subjugate and ostracize people who live outside of the power structures of dominant organized religion. We also acknowledge that “religion” as a term is not adequate. It does not universally define the myriad cultural ways societies connect to what they find sacred. It omits beliefs that are not part of the religious framework defined by colonial power structures. While religion includes the experience of spirituality, participation in organized religion is not a universal human experience. We’ll use the terms “spirituality” and “spiritual belief systems” in this chapter to include societies and communities that do not define themselves using the language of religion.

The Cultural Universal of Spirituality

What then is spirituality, and what is a spiritual belief system? Psychologist Kenneth Pargament defined spirituality as “the search for the sacred” (Pargament 1999:12). As a psychologist, his focus was on the personal and individual experience that all humans have with what is divine, mystical, or transcendent to them.

Applying a sociological lens, spirituality may be a label that groups use to define their own traditions. For example, author Christopher Peters calls his tradition “Earth-based spirituality.” He is a member of the Pohlik-lah (Yurok) and Karuk Tribes in Northwestern California. (Optional: Read more about the Karuk Tribe [Website].) He shares, “Our primary purpose in life is to heal and renew the Earth. We are put here for no other reason” (Peters 2012). Other people may refer to their beliefs as interspiritual. Mystic Wayne Teasdale calls interspiritual the idea that “beneath the diversity of theological beliefs, rites, and observances lies a deeper unity of experience that is our shared spiritual heritage” (Teasdale 2003).

Medical educator Christina Puchalski defines spirituality as “the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred” (Puchalski et al. 2014). This definition combines the individual and social experience.

However, there is also a more structural aspect to spirituality in societies. In Chapter 2, we referred to a system as a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior. When members of societies interact and create meaning out of shared spiritual beliefs, they develop a system of beliefs and practices together. In fact, Durkheim referred to religion as a “unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things” (Durkheim 1912:62). But if we look at those beliefs and practices with a universal lens not based in white supremacy, those beliefs are not necessarily organized into religions.

Building on Puchalski’s definition, we’ll call a spiritual belief system: a series of related beliefs and practices of a society that help members seek and express meaning and purpose. This system is what allows members to experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.

Going Deeper

To learn more about spirituality in the United States, read key findings from a report by the Fetzer Institute: “What Does Spirituality Mean to Us?” [Website]. As you review this research, you will see art from many people. Using images or drawings to gather responses [Website] is a unique but powerful way to gather sociological data.

Licenses and Attributions for Religion, Spiritual Belief Systems, and Power

Open Content, Original

“Religion, Spiritual Belief Systems, and Power” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.5. “Paint Your Faith Mural in Toronto” is on Flickr, by Bernard Spragg. NZ and in the public domain. Mural by the United Church of Canada and artists Siloette, Elicser, Mediah, and Chor Boogie.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

a series of related beliefs and practices of a society that help members seek and express meaning and purpose.

the belief, theory, or doctrine that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups, and are therefore rightfully the dominant group in any society.