9.6 Resilience, Resistance, and Justice

Feminist sociology, critical race, and queer perspectives reflect the realities of everyday lives. As perspectives, they also challenge society to rethink the status quo of dominant social structures. But finding ways to exist and organize against belief systems that are racist, patriarchal, and discriminatory against non-binary people is critical. Religion and spiritual belief can be powerful influencers for groups as they work for this kind of social justice.

This section will focus on ways that organized religion can both maintain oppressive social structures and dismantle them. Each example highlights how oppressed groups apply spiritual belief systems and the organization of religions to live with resilience, act in resistance, and dismantle harmful social structures.

Slavery, Civil Rights, and the Black Church

The harm of slavery is complex. White enslavers used Christianity to support the system of slavery in the United States. In this theology, they incorrectly asserted that men and women of African descent could not morally and ethically discern right from wrong. Enslavers believed that enslaved men and women were inherently sinful and morally inferior even after they converted to Christianity (Pierce 2015).

In these ways, the system of slavery was based on white supremacy. The doctrines of Christianity were twisted to shatter Black families and ensure the economic advantages of wealthy white slave owners. Some Christian churches even sponsored slave ships to capture and transport enslaved Africans to the states (Pierce 2015 in Weil 2019).

When enslavers permitted enslaved people to go to church, white enslavers or preachers taught the Christian lessons. Their religious messages typically glorified the “civilizing” paternalism of enslavers. They were based on proslavery theology that relied on a literal interpretation of the Bible to justify racially based slavery. This literal interpretation is a component of religious fundamentalism, which we discussed in the previous section.

For example, the King James Bible, widely printed during the slavery era (Cedarville University Digital Commons n.d.) reads: “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ” (Ephesians 6:5, King James Bible 1611). It is generally accepted that “servant” meant “slave.” Both the Old and New Testaments refer to slavery often.

Enslavers used these interpretations of Christianity as a means of social control. More directly, enslavers and preachers at the pulpit emphasized a scriptural message of obedience to white people and a better day awaiting enslaved people in heaven.

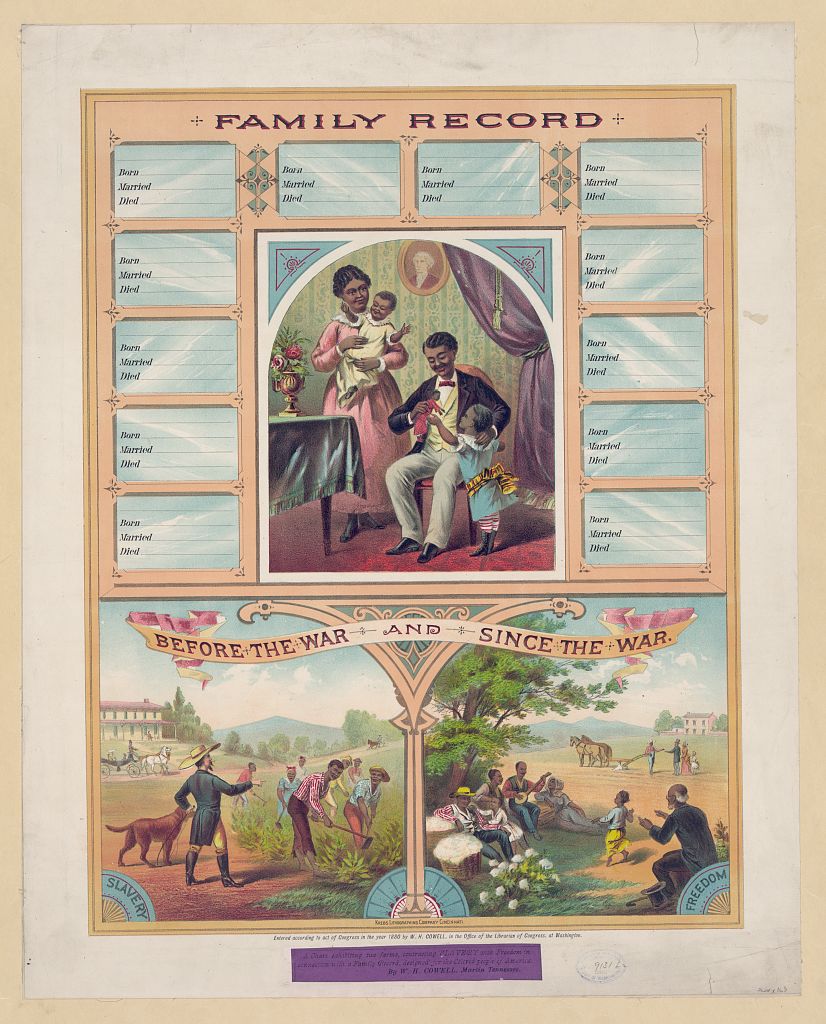

Obvious contradictions between God’s word and the cruelty of enslavers did not pass unnoticed by many enslaved African Americans. They created and practiced their own versions of Christianity, typically incorporating aspects of traditional African spiritualities or Islam. The rituals, dances, use of various plants by healers, naming patterns, and making of musical instruments created spiritual connections to their African past while also providing a sense of community and identity (figure 9.21). Other enslaved people resisted Christianity altogether by fully retaining their native African and Islamic practices.

Simultaneously, some enslaved people were attracted to the Methodist and Baptist church’s response to scripture and became preachers. As English literacy advanced for people in slavery, spiritual songs that referenced the Exodus (the biblical account of the Hebrews’ escape from slavery in Egypt), such as “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” allowed them to freely express messages of hope, struggle, and overcoming adversity. They focused on the uplifting message of being freed from bondage.

After slavery was abolished and Black U.S. residents were liberated from white-controlled churches, they were able to remake their religious worlds according to their own social and spiritual desires. Black people created their own churches and, within them, began to heal and develop their own social structures.

For example, these new churches supported the healing of family systems that had previously been under the control of slavery. For some, this meant opting for state and religious recognition, as many freed people rushed to get married in formal and legal wedding ceremonies (figure 9.22). New Black churches also became the foundation of state and national organizations that supported anti-racist politics.

Years later, Black churches provided the leadership and organizational structures that energized the civil rights movement. Many U.S. residents know Martin Luther King Jr. as an activist. Not everyone knows that he was a minister and had a doctorate in divinity. King was part of the social gospel movement, which emerged in response to the abuses of industrialism of the 20th century. Cheap labor bred poverty, hopelessness was prevalent, and the extreme wealth of business owners was evident (PBS n.d.). The social gospel perspective viewed racial and economic oppression as social evils that Christians had a moral duty to resist. The church was seen as instrumental to both individual and social salvation.

Sociologists often credit the social gospel movement and the organizational power of “the Black Church” as part of the civil rights movement’s success. It sustained activists during the civil rights era in the face of violence and emboldened individuals to stand up to a white supremacist system.

Optional: Watch the 3.5-minute video “The Role of the African-American Church in the Civil Rights Movement” [Streaming Video] for a summary of this history (figure 9.23). As you watch, please consider the specific ways that spiritual belief systems and religious organizations played a role in the social changes of the civil rights movement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLxddvkYmic

The Christianity practiced by white enslavers supported genocidal economic systems in the United States. That same Christianity, and at times the preservation of African and Islamic beliefs, supported resilience and resistance to slavery. Later, Christianity, as practiced by black freedom activists of the civil rights movement, drove a fight for social justice.

Syncretism and Día de los Muertos

The worship style of combining two religions, as enslaved people did in the United States, is seen globally and throughout history. It is known as religious syncretism, the process by which the beliefs and practices of one religion are fused with or assimilated into another spiritual belief system. In some parts of the world, syncretism has been a powerful way to resist colonization in plain sight.

One illustration of this is Día de los Muertos (“Day of the Dead”), an event to remember and connect with loved ones who have died. While the celebration likely originated with earlier practices of Indigenous groups, we know that Día de los Muertos was important to people who were part of the Aztec empire of the 1300s to 1500s in central and southern Mexico. Today, it’s observed by people of Mexican and Indigenous Mexican heritage.

Families create altars with photos of their ancestors, along with ofrendas, or offerings, intended to welcome the deceased to the altar setting. They add the food and drink that the person loved in life and other objects that capture their unique personalities. The altars are decorated with candles, religious statues, rosaries, and flowers—especially marigolds, whose fragrance is said to lead souls from their burial place to their family homes. Celebrations happen at home, public gatherings, and parades (figure 9.24).

The persistence of Día de los Muertos is impressive, considering the story of colonization that surrounded its origins. When the Spanish arrived in Mexico in 1519, they were awed by the complexity of the Aztec world. Tenochtitlán, founded in 1325, was the largest Aztec population hub and cultural center (now present-day Mexico City). Upon arriving, one conquistador wrote: “It was all so wonderful that I do not know how to describe this first glimpse of things never heard of, seen or dreamed of before” (Fredrick 2019) (figure 9.25).

The Spanish conquistadors had to work hard to conquer such a complex and organized society. The Spanish formed alliances with Indigenous empires that rivaled the Aztecs, aiming to seize their land for the Spanish crown and plunder gold and other resources. Between the violence, disease contracted by exposure to the Europeans, and Spain’s advanced weaponry, the Aztec empire lost power in 1521. A century later, after more waves of disease, the Aztec population plunged from what was once 5 to 6 million at its peak, to around 1 million (Callaway 2017).

As part of this conquest, Spanish missionaries worked with conquerors to destroy the belief systems and practices of the Aztecs, while forcing their conversion to Catholicism. They forbade rituals and celebrations and burned temples, books, and other sacred objects, or appropriated them to be part of local Catholic rituals. For example, baptisms were conducted in basins traditionally used for sacrifices. Catholic churches were built on top of destroyed temples (Sherry n.d.). They also appropriated spiritual symbols, incorporating them into their own, such as adding Indigenous symbols to Christian crosses. This was cultural genocide (a term we first introduced in Chapter 1).

The Aztec people had a complex belief system around death, the afterlife, and the divine that was at least 5,000 years old. For example, they recognized many layers of the underworld. One is the final destination for all people who have died of natural causes. Another is for warriors who died in combat, people sacrificed to the sun, and women who died while giving birth for the first time. Yet another layer is for those whose death was caused by the water element and for infants who died while still nursing from their mothers (University of New Mexico Latin American and Iberian Institute n.d.).

Their practices included using ancestor mortuary bundles, particular ways to wrap dead bodies. They also worshiped Mictecacihuatl and Mictlantecuhtli (figure 9.26), the goddess and god of the underworld. In Aztec stories, Mictecacihuatl and Mictlantecuhtli meet the souls of the dead and preside over the afterlife.

Spanish conquerors could not convince the Aztec people to stop practicing these rituals, which were essential to their worldview and their connection to the underworld. The Spanish witnessed the power of these beliefs and practices to stabilize society. So they changed the dates of the festivities celebrating the dead to early November, to coincide with the three-day Christian observance related to All Souls’ Day. This succeeded in connecting worship of the underworld to Catholicism, but many of the Aztec practices and beliefs remained (Farah n.d.).

Later, the celebration became known as Día de Los Muertos (Nutini 1988). Optional: Watch the 5-minute video “Día de los Muertos: Lake Pátzcuaro” [Streaming Video] (figure 9.27) that shows how one community in Mexico practices for the Day of the Dead celebration. As you watch, see if you can notice symbols from Catholicism that are filmed. What aspects of this celebration do you imagine prompt solidarity and stability for the people who celebrate?

Over time, many Indigenous Peoples have blended Catholicism with their own customs and ancestral worldviews as a means of resistance. Evidence remains today of religious syncretism throughout Latin America. It is common in several countries, for example, to make offerings of food, drinks, candles, or flowers to entities that are both deities from Indigenous traditions and saints from Catholicism. According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2013 and 2014, about half of Mexican Catholics reported “medium” to “high” levels of engagement with Indigenous beliefs and practices. About 80 percent of Mexicans identified as Catholic, but many practiced a unique version of Catholicism that includes pre-Hispanic traditions (Pew Research Center 2014).

This longstanding and vibrant celebration is not just a mixture of Indigenous and Spanish traditions. It is also a profound example of Indigenous resistance to 500 years of colonialism (Felipe Ramos 2018). As Roberto Cintli Rodríguez writes, it is an example of how Indigenous Peoples “accepted Christianity into their cosmovision for purposes of cultural survival” (Rodríguez 2014 in Felipe Ramos 2018).

Liberation Theology

Hundreds of years after colonizing the Aztec territories, the Catholic Church hosted a movement that brought some acknowledgment to the harm it sponsored in the Americas. The liberation theology movement was a religious movement of the 1960s and 1970s that combined Christian principles with political activism to enact social change.

Scholar and social ethicist Sharon Welch describes liberation theology as “concerned with political and social transformation and the role that religion plays both in fostering liberation and in maintaining oppression” (Welch 2017:15). Its inspiration came from the rapid changes of industrialization and the inequalities it fostered. Business owners were able to amass riches. But for workers, industrialization meant long work hours, dangerous child labor, and a sharp decline in buying power.

Some Catholic leaders wanted to support the status quo in order to remain part of the economic systems in place. Similar to the way Christianity was used to legitimize slavery in the United States, these leaders found biblical and theological justifications for the oppression that this structure and the people within it caused (Singer n.d.). But, eventually, the Catholic Church began to grapple with how to respond to this new economy and the harm it brought.

Colonial-era messages that the Catholic Church was delivering to the poor included a promise of eternal salvation. Followers of liberation theology found this kept the poor subdued as they waited for a better afterlife. In contrast, they wanted the church to assume the responsibility of liberating the poor from oppression and suffering on earth. They demanded that the church move beyond simple charity work toward a more active role in promoting social justice (figure 9.28).

In 1965, structural reforms provided an institutional foundation for liberation theology in the Catholic Church. During Vatican II, a large conference of Roman Catholic leaders, Pope John XXIII established a new platform built on the idea of the church as a servant of the people rather than a partner with governments in asserting power over them (Tombs 2002). He made reforms designed to reposition the church away from a socially privileged institution. Vatican II changed the rules so Mass could be celebrated in everyday language instead of in Latin. The altar was turned so priests faced the people and spoke directly to them. The council also added more biblical texts to the Mass and encouraged people to read the Bible (Guardado 2022).

Small groups of lay people (non-clergy) were organized to serve smaller municipalities. They provided food, water, sewage disposal, and electricity to communities. They taught basic literary skills and religious teachings and encouraged civilians to participate in civil society. These efforts were to empower the poor to better question their own conditions, question society, and organize politically (Singer n.d.).

Liberation theology was further influenced by missionaries and other members of the church who were awakening to the harmful impacts of globalization, acknowledging the impacts of colonialism. The people in the Global South were becoming poorer, and the people of the Global North were exploiting them to get richer. Especially in Latin America, priests and others in leadership began to link poverty with dependency perspectives (introduced in Chapter 4) as they explained economic inequality.

The term institutionalized violence emerged at this time, a form of violence in which some social structure or social institution may harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs. Church leaders sensitive to these realities began asking what their faith had to do with these struggles (Guardado 2022).

Liberation theologians brought support and solidarity to the social and political struggles of Latin America and the world. As civil protest and demand for change increased in the 1970s and 1980s, governments of Latin America began to adopt repressive measures to establish social control. Many of these military actions were backed by U.S. funds, which fueled further solidarity from followers of the liberation theology movement, now on a political international scale (Tombs 2002).

Two Catholic leaders became forerunners in this movement. Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino was critical of both the social and economic injustice he believed to be responsible for poverty in Latin America. He was also critical of the clergy within the Catholic Church that supported those systems. He prioritized his work on education, research, engaging with lawmakers, and collaborating with grassroots organizations.

St. Oscar Romero also worked to protest poverty and dismantle the structures that supported injustice. He worked in El Salvador as a priest during the country’s civil war of 1979 to 1992. During this era, 57 percent of the usable land in the country was controlled by 2 percent of the population. Sixteen families in El Salvador owned an exorbitant amount of land, the same amount used by 230,000 of the poorer families.

This impacted Romero greatly, as did the political and economic violence in El Salvador during the war. Military and paramilitary death squads murdered tens of thousands of men, women, and children to quell the government‘s fears of communism, under the guise of “law and order.” In 1977, a right-wing paramilitary group forced all Jesuits to leave the country or be executed.

Romero was assassinated while presiding at a memorial Mass in 1980: a punishment for his work with the poor to help them organize and secure self-determination. In 1981, he posthumously won a Nobel Peace Prize, and he was canonized (made a saint) by the Catholic Church in 2018 (The Kellogg Institute for International Studies n.d.) (figure 9.29).

Eventually, the Vatican became alarmed by the radical changes influenced and supported by liberation theology. Opponents argued it could lead to disunity and excessive focus on material success (Lynch 1994). By the 1990s, under a new pope, the church had begun to curb involvement in the movement, mostly by appointing conservative bishops in Latin America. The Vatican and more traditional sects of Catholicism proposed a watered-down version of liberation theology that avoided the disruption that liberation entailed (Singer n.d.).

It would be interesting to hear what Marx and Weber thought about the impact of liberation theology, had they been alive in those years. Weber would likely have been interested in the cultural changes that liberation theologians promoted and how they influenced criticism of the economic status quo. Marx would likely have been interested in the vast social and economic changes that liberation thought introduced. They turn his perspective of religion controlling the masses on its head. Liberation theology rethought the power structures of Latin American society and showed that belief, economic analysis, and activism could dramatically change the roles and function of religion.

Protesting Gender-Based Violence

The liberation theology movement of Latin America has several related schools of thought. Paulo Freire (introduced in Chapter 8) applied principles of liberation in his revolutionary work of educating the poor. Black theologies of liberation and Islamic theologies of liberation see organized religion as a means of changing the material conditions of marginalized and oppressed groups. Queer theologies of liberation examine society’s definitions of gender and sexuality, with the goal of revealing the social and power structures at play in our everyday lives.

Feminist liberation is also part of this school of thought. It began in the 1960s as well and seeks to free women from oppression and male supremacy. A central concern of feminist liberation theory is gender-based violence, harmful acts directed against a person because of their gender and expectations of their role in a society or culture (The United Nations Refugee Agency n.d.) (figure 9.30). In examining gender-based violence, we can see how it is both supported and challenged by religious organizations.

Gender-based violence is a relatively new area of research in social science. Researchers acknowledge that religion is not the only institution that supports gender-related abuse. However, this kind of violence often happens in families, and religious communities can cover up abuses due to their view of the sanctity of the family. In these instances, the family is considered a divinely ordained institution, and its preservation takes precedence over denouncing domestic violence (Nason-Clark et al. 2018; Nason-Clark 2000).

The ability of families and religious organizations to hide violence makes gender-based violence a challenging topic to study globally. In the West, this violence is difficult to study because of the legal separation of church and state. The laws give religious institutions exemption from some legal responsibilities, so churches are not required to report cases of abuse to state authorities (McPhillips and Page 2022).

However, since the 1980s, there have been ample studies that shed light on the extent and severity of gender-based violence in Western religious communities (Aune and Barnes 2018). Recent scandals in both the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations in the United States have revealed some disturbing facts on the extent and cover-up of sexual violence (Hidalgo and Doyle 2007; Plante 2020).

Gender-based violence takes place at three levels: physical, legal, and social. For example, child marriage is internationally recognized as a form of gender-based violence. It puts girls at increased risk of sexual, physical, and psychological violence throughout their lives. Nevertheless, it is a legal practice in some countries. In other countries, women are considered property of men or need to be under the care or control of a male guardian.

Gender-based violence in some Islamic societies is also a subject of inquiry. Shari’a is the overall way of life in Islam, according to traditional, early interpretations. For many Muslims, the penalties outlined in scripture for deviating from Shari’a were designed for a specific historical context. They are inapplicable to the very different modern world. Most Muslim-identifying governments do not allow severe penalties.

However, countries like Iran, Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia have established laws based on those stricter Shari’a interpretations with severe penalties (Abdullahi n.d.). Sometimes women who are disobedient or viewed as dishonoring their families are beaten or killed by their family members. These forms of gender-based violence may be endorsed by more extremist Islamic leaders. In some cases, due to religious, cultural, and legal constraints, victims cannot or are unwilling to come forward to register their cases (Naciri 2018).

Protection and Resistance in Iran

Iran has a poignant story of struggle with gender-based violence. For decades before the revolution of 1979 (figure 9.31), women rallied for progressive changes to family law to protect their human rights. Their efforts culminated in the Family Protection Law of 1967, which, according to Neeki Memarzadeh, “put Iran into the forefront of the movement for law reform in the Muslim World” (Hinchcliffe 1968:517).

This law took many family disputes and regulations out of the hands of Shari’a law, the body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. Women could then navigate family concerns in secular courts. The Family Protection Law also expanded women’s rights to seek divorce and extended mothers’ rights to custody of their children (Memarzadeh 2023). These changes emboldened women to seek attention from courts in the event of domestic abuse.

After the revolution, Iran became an Islamic Republic. It was built to enforce laws compatible with Shari’a. Thus, it has a theocratic government, one where religious leaders rule in the name of God or gods and interpret their holy texts as law. The new government suspended the Family Protection Law and implemented many laws that diminished the rights and protection of women. The age of marriage for girls was reduced from 18 to 9. Only men could seek a divorce. The hijab became mandatory in public. If women did not wear one, they could be punished with 60 lashes from a whip (Esfandiari 2020).

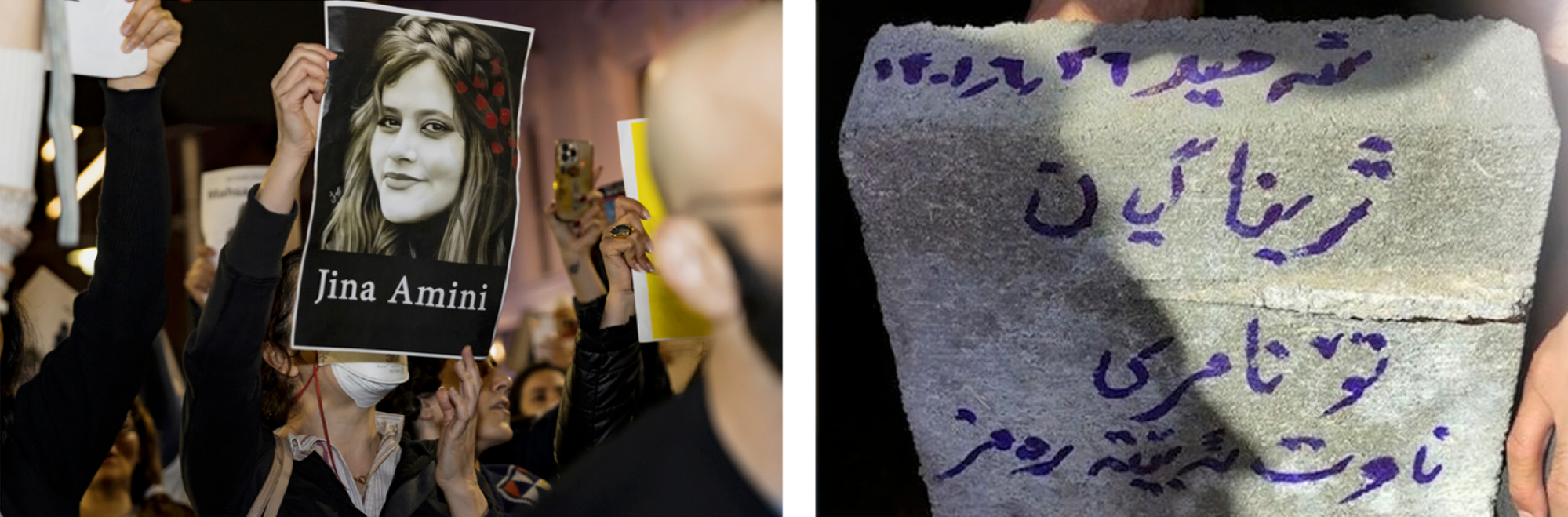

Since 1979, Iranian women have formed a powerful movement for their rights in the face of a strict and oppressive government. They have also experienced tragedy. In 2022, Jina Amini, who is also known as Mahsa, was a young Kurdish-Iranian woman. The morality police in Iran murdered her because she allegedly violated the law that requires women to wear a hijab. (The police say that she experienced health problems while in custody.)

Adding to the concern and outrage is that Kurdish people in Iran experience considerable ethnic discrimination. Iran is a predominantly Shiite country, and most of Iran’s Kurds are Sunni, many of whom opposed the adoption of Shiism (Shia) as the official state religion after the revolution (Nada and Crahan 2021). Amnesty International reports a “double oppression” suffered by Kurdish women and girls in Iran, for their ethnicity and gender (Amnesty International 2008).

The epithet on Amini’s tombstone reads, in Kurdish: “Jina, dear! You didn’t die. Your name will be a code [rallying call]” (Lace-Evans and Auer 2022) (right). Amini’s death sparked protests in Iran and internationally.

Jina Amini’s death sparked protests in Iran and internationally (figure 9.32). Protesters attacked symbols of the regime. Some women protesters removed their hijab as a way of resisting. The photo in figure 9.32 is an epithet written in Kurdish on Amini’s tombstone. It reads, “Jina, dear! You will not die. Your name will be a code [rallying call]” (Lace-Evans and Auer 2022). This renewed women’s rights movement in Iran is gaining support around the world. In 2022, people marched in protest in Seoul, Beirut, Santiago, New York, Rome, London, and other places around the world. Some women cut their hair in solidarity.

Many religious and spiritual traditions include cutting hair as a symbolic gesture or ritual. Buddhist monks shave their heads when they take vows, and some spiritual traditions call for family members to shave their heads when a loved one dies. In the case of Amini’s death, protesters are giving an ancient ritual a modern twist by cutting their hair to show solidarity.

Watch this 1:45-minute video, “Iran Protests: Why Is Cutting Hair an Act of Rebellion?” [Streaming Video] (figure 9.33). As you do, consider: How are the protesters using religious beliefs and practices to initiate social change?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfBB50ktdPw

In the story of Iran and women’s rights, we see religious power and beliefs on both sides of the conflict. The Islamic Republic uses religious beliefs and organizations to prevent social change. The story of gender violence, women’s rights, and religion is played out on the world stage. The players use religious beliefs and practices to uphold their existing power or to resist it.

Going Deeper

To learn more about Martin Luther King Jr. describing the Social Gospel, watch: “Martin Luther King, Jr. – Influence of Social Gospel Mov’t” [Streaming Video].

For more information on “the Black Church” in the United States, watch the PBS episode “The Black Church” [Streaming Video].

For more information on the connection between white supremacy and Christianity, read and watch “White Supremacist Ideas Have Historical Roots In U.S. Christianity” [Website].

For more on the Aztec god and goddess of the underworld in figure 9.26, read: “Mictlantecuhtli” [Website] and “Mictecacihuatl” [Website].

For more information on femicide protests alongside Day of the Dead celebrations, watch “Protest Against Femicide on Mexico’s Day of Dead” [Streaming Video] and “Women in Mexico Protest Femicide on Día de los Muertos” [Streaming Video].

To learn more about St. Oscar Romero, watch “Oscar Romero” [Streaming Video] from the Oscar Romero Trust and read the article “Archbishop Oscar Romero” [Website].

Licenses and Attributions for Resilience, Resistance, and Justice

Open Content, Original

“Resilience, Resistance, and Justice” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Images added by Aimee Samara Krouskop.

“Syncretism and Día de los Muertos” and “Liberation Theology” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Protesting Gender-Based Violence” by Arfa Aflatooni and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Slavery, Civil Rights, and the Black Church” includes content adapted from: “African Americans in the Antebellum United States” by P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Sylvie Waskiewicz, and Paul Vickery in U.S. History, Openstax, licensed under CC BY 4.0; “Slave Religion” in “HIST114 – United States to 1870” by the American Women’s College, licensed under CC BY 4.0; “Politics of Reconstruction” and “Spiritual Life: Public and Secret” in “African American History and Culture” by Florida State University at Jacksonville and Scott Matthews, Lumen Learning, licensed under CC BY 4.0; and “Understanding the Future of Black Politics Means Understanding the Future of the Black Church” by Eric L. McDaniel and Maraam Dwidar, London School of Economics, is licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0. Modifications by Kimberly Puttman, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include adding content to emphasize religion and social change.

“Liberation Theology Movement” definition from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.21. The Old Plantation is on Wikipedia, by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, Virginia and in the public domain.

Figure 9.22. “Image of the Family Record” is at the Library of Congress, by Krebs Lithographing Company, and in the public domain.

Figure 9.24. “Aztec Dancer” is on Flickr, by Tom Hilton, and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.25. “Photo of Wall with Stucco Covered Skulls at the Templo Mayor, Aztec Origin, Mexico City” by Nan Palmero is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.26. “Photo of a Mictecacihuatl carving” by FlyingCrimsonPig is licensed under CC BY 2.0 DEED (left). “Photo of a Person Representing Mictlantecuhtli” by Natalia Mondragón is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (right).

Figure 9.28. En la Cena Ecológica del Reino/At the Kingdom’s Ecological Dinner by Maximino Cerezo Barredo is property of the Latin American People.

Figure 9.29. “Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez” is on Wikimedia Commons, and in the public domain (left). “Beatificación de Monseñor Oscar Arnulfo Romero” is on Flickr, by Cancillería del Ecuador and licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0 (right).

Figure 9.30. “Seamstresses from Quetta, Pakistan” is on Flickr, by UN Women/Henriette Bjoerge and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.23. “The Role of the African American Church in the Civil Rights Movement” by Manning Marabel, NBC News Learn, is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.27. “Día de los Muertos: Lake Pátzcuaro” by Jose Cuervo and director Monica Alvarez is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.31. “Students at Tehran University, Iran, in 1971” is published by NPR, by Kaveh Farrokh/foreignpolicy.com, and included under fair use.

Figure 9.32. “Protesters Gather in Melbourne, Australia” is on Flickr, by Matt Hrkac, and licensed under CC BY 2.0 (left). “The epithet on Amini’s tombstone” is published on 5cents a pound and included under fair use (right).

Figure 9.33. “Iran Protests: Why Is Cutting Hair an Act of Rebellion?”, by Euronews, is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

a state where "everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life.”

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

A religious movement that requires a strict and typically literal interpretation of core texts and adherence to traditional beliefs, doctrines, and rituals.

a way to regulate, enforce, and encourage conformity to norms both formally and informally.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

the process by which the beliefs and practices of one religion are fused with or assimilated into another spiritual belief system.

a series of related beliefs and practices of a society that help members seek and express meaning and purpose.

the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world or universe held by an individual or group.

the military, economic, and ideological conquest of one society by another. It results in one society settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

a religious movement that combines Christian principles with political activism to enact social change.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

a system for the production, distribution, and consumption of the goods and services within a society.

the communities, groups, and organizations that function outside of government to provide support and advocacy for certain people or issues in society.

the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations due to cross-national exchanges of goods and services, technology, investments, people, ideas, and information.

a form of violence in which some social structure or social institution may harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs.

the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups. This influence occurs through the relationship between institutions and social practices.

figures, extents, or amounts of phenomena that we are investigating.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a philosophical and economic ideology within the socialist framework that advocates for public rather than private ownership, especially of the means of production.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

the capacity to actively and independently choose and to affect change

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

one where religious leaders rule in the name of God or gods who interpret their holy texts as law.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

the belief, theory, or doctrine that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups, and are therefore rightfully the dominant group in any society.