6.5 Structural Issues of Houselessness

Nora Karena

Let’s consider how, for many communities, housing insecurity is a legacy of historic patterns of removal, exclusion and discrimination that have specifically targeted Native Americans, African Americans, and LGBTQIA+ families.

6.5.1 Structural Causes of Indigenous Houselessness

In Multnomah County, Oregon, Indigenous people make up 2.5 % of the population, but 10% of people who are unhoused (Schmid 2017). Native Americans have the highest poverty rate of any racial-ethnic group. As of 2021, 25.9% of Native Americans experienced poverty, according to the US Census (KFF 2022).

The government’s control over Indigenous people’s living conditions contributes to this circumstance. When the US government forcibly removed Native Americans to reservation lands, it also retained ownership of that land. The government holds reservation lands “in trust” for the tribal nations. Trusts are financial arrangements that allow a third-party trustee to hold and control assets on behalf of a beneficiary. The underlying justification for most trusts is that the beneficiaries can not be trusted to properly manage their assets. While this might be acceptable for minor children who inherit large sums of money, this paternalistic oversight of Native American people perpetuates systems of displacement and genocide that have been visited upon Indigenous people in the Americas for 600 years.

We hear about tribal rights and casinos, and debate using harmful stereotypical images for sports teams. However, most non-tribal members don’t recognize how the US government limits homeownership for Native Americans (Schaefer Riley 2016). For example, Native Americans who fought alongside White GIs in World War II have been denied the opportunity to create the same generational wealth as other American veterans. Because reservation land is held in trust, the returning Native American veterans were excluded from the GI Bill home loans for homes on reservation land. Although not all Indigenous people agree that private land ownership is the right goal today, the lack of access to home ownership via the GI Bill is one of several discriminatory policies that racialized home ownership in the mid-20th Century. Let’s look at the discriminatory lending and zoning practices to learn more.

6.5.2 Creating Under-resourced Communities: Racism, Segregation, Redlining

Figure 6.16. People created racially segregated neighborhoods through deliberate creation and implementation of racist laws, policies and practices. Although residential segregation is now illegal, neighborhoods remain segregated. Why do you think this is?

In this section, we talk about residential segregation, the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods. To understand the roots of racially segregated housing policies, we need to start with enslavement and the racist ideas that justified it. You might remember that Ibram X. Kendi asserts that any policies that result in racial inequity and ideas that justify or excuse racial inequity are racist. Racist ideas about the supposed inferiority of people who are Black include ideas about “degeneracy,” cleanliness, laziness, sexual habits, drug use, and dishonesty. Even though slavery was illegal in many northern states, people in northern cities were still taught that Black people were different from and inferior to White people.

As early as 1830, free Black people who made their way to northern cities were not welcome in many communities. Poor people who were Black lived in racially segregated housing. Often, they had to move when developers and landowners found more profitable uses for the land. Even affluent and educated Black people with the resources to buy property experienced displacement and discrimination.

In 1850, Seneca Village, a thriving Black community of 1600 people outside of New York City, was displaced by eminent domain to build Central Park (Staples 2019). The community boasted successful businesses, a vibrant church, and a school. Newspapers and magazines, however, relied on racist ideas and racial epithets (like the n-word) to describe the community as a decrepit shantytown. They also claimed the residents were unable to properly care for the valuable real estate they held. Residents who owned the land were compensated, but the land was undervalued. This land grab was conveniently justified by the emergence of the powerful racist idea that property values go down where Black people live. If you’d like to read this article for yourself, please explore this Gotham Gazette Article, Death of Seneca Village.

Between 1910 and 1970, in the Great Migration period, more than 6 million Black people relocated from the rural south to cities in the north and west in search of better jobs. Many people in the North accepted the same racist ideas that fueled the brutal racism of the south. As in New York, a century before, many White people feared that home ownership by Black people would lower property values.

During the postwar housing boom of the ’40s and ’50s, the GI Bill provided low-interest home loans to returning veterans. New suburban communities sprang up. The American dream of home ownership became a reality across the US, at least for White Americans. According to Heather McGee:

The mortgage benefit in the GI bill pushed the postwar home ownership rate to three out of four white families – but with federally sanctioned housing discrimination, the black and Latinx rates stayed at around two out of five, despite the attempts of veterans of color to participate. (McGee 2021:22)

This structural racism also occurred with standard mortgage loans. Black families were routinely denied loans for the new suburban homes. They were forced to buy houses in older, more urban communities, like the Albina neighborhood in Portland, Oregon.

Once Black families bought homes in urban neighborhoods, real estate agents routinely took advantage of White homeowners’ fears of lower property values to persuade them to sell their property at a low price. The agents then turned a profit, reselling them to Black families at higher prices. Lenders charged them higher interest rates. Realtors and lenders made big profits from this “block-busting” practice.

They also succeeded in lowering the value of homes in rapidly segregated neighborhoods. Since these homes were assessed at low value, the tax base of these neighborhoods was restricted. Tax-funded infrastructure, like public works and schools, was underfunded. In other words, it was not Black people’s presence but White homeowners’ prejudice, grounded in racist ideas, that led to lower property values and created under-resourced communities.

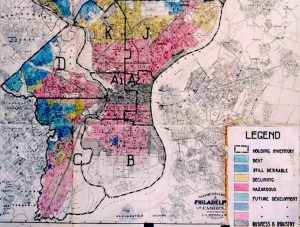

Figure 6.17. Lending institutions and the federal government created maps in which the places where People of Color and/or foreign-born lived were colored red and designated to be “dangerous” or “risky.”

Redlining is the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable. The federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933, and the Federal Housing Association (FHA) in 1934, and the real estate industry worked to segregate Whites from other groups to preserve property values in neighborhoods where White people lived.

Lending institutions and the federal government did this by creating maps in which the places where People of Color and/or immigrants lived were colored red. Then, those areas were designated to be “dangerous” or “risky” in terms of loaning practices.

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act, part of the Civil Rights Act, outlawed these practices. The Fair Housing Act is an attempt at providing equitable housing to all. It makes it illegal to discriminate against someone based on skin color, sex, religion, and disability. Also banned is the practice of real estate lowballing, where banks underestimate the value of a home. This practice forces a borrower to come up with a larger down payment to compensate for the lower loan value. Offering higher interest rates, insurance, and terms and conditions to people from historically underrepresented groups is illegal. Denying loans and services based on an applicant’s protected class is also illegal.

Still, much damage was done prior to its passage. For decades, the federal government poured money into home loans that almost exclusively favored White families. Homeownership is the most accessible way to build equity and wealth. It was denied to many historically marginalized families for decades. Once the Fair Housing Act passed, local governments used other legal methods to justify racist real estate practices well into the 2000s.

Today, despite repeated efforts by city officials to create more mixed-race and mixed-income neighborhoods, Portland’s neighborhoods have remained demographically segregated. Gentrification and redevelopment have reduced the available inventory of affordable housing. Portland’s land use planning history has continued to benefit White homeowners while communities of color have been burdened, displaced, excluded, and disproportionately vulnerable to housing insecurity.

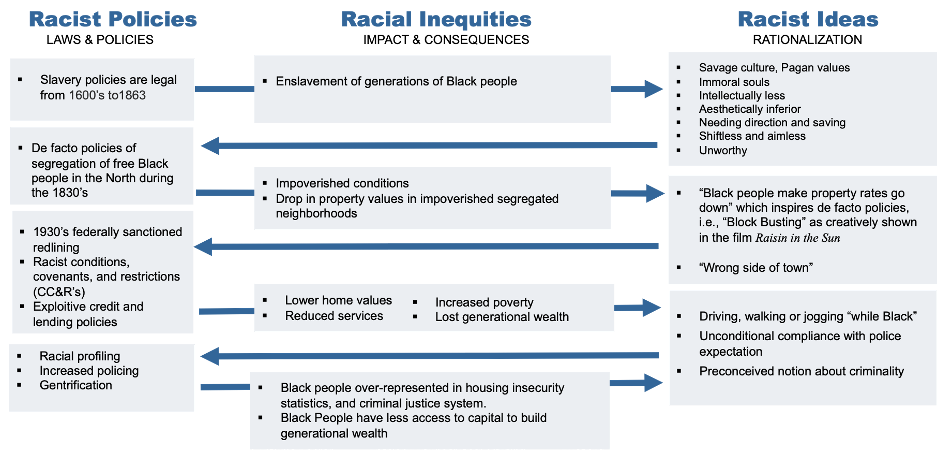

Figure 6.18. Racist Policies, Racist Inequities, and Racist Ideas in Housing: This chart illustrates Ibram X Kendi’s definition of racism as “…a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produce and sustain racial inequities” (2016). Notice the connections between racist policies in housing, racial inequities, and racist ideas. We can say that the entire system is racist because each component reinforces the other and leads to even more racial inequity. Image Description

The experience of Black people in Oregon is a local example of a systemic problem. Please take some time to examine the chart in Figure 6.18. It shows how Racist Policies, Racist Inequalities, and Racist Ideas reinforce each other over time. Starting with the first box, we see that slavery was legal until 1863. Racist laws and policies created the institution of slavery. The impact and consequences of those laws, or racist inequalities, result in millions of people being enslaved. Racist ideas rationalize or normalize the practice of slavery by asserting the false idea that Black people are less than human—that they are immoral, lazy, and stupid.

These false ideas about the character and capabilities of Black people caused both de-facto segregation in the North and legalized segregation in the South. Jim Crow laws in the South and segregated housing policies in the North kept neighborhoods separate. Consequently, Black people lived in poorer neighborhoods, and even when they owned homes, their property was worth less. This reinforced beliefs about inequality—that if Black people moved into your neighborhood.

Over time, these false beliefs solidified into policies such as redlining, restrictive housing covenants, and other laws that further restricted Black people’s access to home ownership. Among other consequences, the lack of home ownership reduced Black families’ possibilities of creating generational wealth, a concept discussed in Chapter 5.

Because there were “right” and “wrong” places for Black people to be, police surveilled Black people who were out of place—walking or driving while Black. They, and other White people often assumed that Black people were criminals if they were outside their own neighborhoods, another racist idea.

These mistaken ideas drove policies and practices around racial profiling and increased policing. Black people are arrested more often, not because they commit more crimes but because they are surveilled more. This cycle creates disproportionate housing instability for Black people and exacerbates other social problems.

6.5.3 Climate-related displacement

As we look at climate displacement worldwide, we see that more people become houseless due to natural disasters than due to conflict or violence. If you want to learn more about climate displacement worldwide, visit Climate Displacement by Country [Website]. A natural disaster is an unexpected natural event that causes significant loss of human life or disruption of essential services like food, water, or shelter (Drabek 2017). Because climate change is increasing, natural disaster rates are also increasing. Hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods damage housing. They decrease the amount of housing in a community. Rates of home ownership decline (Sheldon and Zhan 2018).

People also move because of climate change. Climigration is the act of people relocating to areas less devastated by flooding, storms, drought, lack of clean water, or economic disaster due to the forces of climate change. Many American families relocate as jobs disappear or land becomes flooded or arid. In response to an immediate disaster, many families move to live with relatives or friends. Some families have nowhere to turn.

In response to the increased risks of property loss as oceans warm and sea level rises, lending institutions are beginning to practice bluelining, which designates real estate considered high risk due to low elevation may not qualify for loans. We’ll explore more social impacts of climate change in Chapter 8.

Figure 6.19. Please watch the 6.39 minute video Oregon Already Has a Climate Refugee Crisis [YouTube]. Are you surprised to see climate refugees in Oregon? Transcript

Oregon is experiencing climate change and resulting increases in wildfire activity. Climate-driven wildfires in 2020 burned over a million acres and displaced tens of thousands of Oregonians. (Oregon Forest Resources 2023). In southern Oregon, where affordable housing was already limited, low-income renters were left with few options. As of 2022, more than 500 survivors of the 2020 wildfires were living in shelters (Arden 2022). Please watch the 6:39 minute video in Figure 6.19 to see how climate-related housing insecurity is impacting survivors of the Jackson County Fires.

In Chapter 14, we examine the impacts of the Echo Mountain fire, which destroyed 288 homes and 339 structures in Lincoln County, Oregon. Over two years later, only about half of the families impacted by the fire have returned home.

6.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Structural Issues of Houselessness

Open Content, Original

“Structural Issues of Houselessness” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Redlining,” “Bluelining,” and “Indigenous People and Reservation Land” are partially adapted from “Finding a Home: Inequities” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Carla Medel, Katherine Hemlock, and Shonna Dempsey, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include adding new content about structural racism to Redlining, adding content about natural disasters and wildfires to Bluelining, and editing and updating Indigenous People and Reservation Land for context.

“Bluelining” and “Residential Segregation” definitions from Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press] by Elizabeth B. Pearce are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.16. “Sign: ‘We Want White Tenants in our White Community” by Arthur Seigel, Office of War Information is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.17. “Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Philadelphia redlining map” from Wikipedia is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.18. “Racist Policies, Racist Inequities, and Racist Ideas in Housing” by Nora Karena, Michelle Osborne, and Toni Belcher is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.19. “Video: Oregon Already Has a Climate Refugee Crisis” by Vice News is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.