7.4 Explaining the Social Problem of Belonging

Kimberly Puttman

You may already be thinking about some of the reasons that people have different experiences of belonging. You might have some reasons that families have unequal access to resources and legal protection from the state. Let’s see what sociologists have to say.

7.4.1 Functionalist

Some sociologists examine the purpose of family in society. Functionalists uphold the notion that families are an important social institution and play a key role in stabilizing society. They also note that family members take on status roles in a marriage or family. The family and its members perform certain functions that facilitate the prosperity and development of society. For example, functionalists argue that families have a division of labor. In the nuclear family, men work outside the home, and earn money. Women work inside the home and care for all of the family members.

These essentialist versions of early sociologists are widely criticized today, because they assume women are often or always mothers and work inside the home, and that men are always or often fathers and work outside the home. However, the functionalists can help us understand the social problem of belonging by looking at how families support belonging.

For example, immigrant families face many challenges. Immigrant families are disproportionately poor. They experience nativism, laws and policies which privilege citizens over non-citizens. For example, many immigrants can’t use the usual governmental social safety nets.

A function of the family for immigrants, then, is to ensure survival of the members of that family. The family becomes an essential survival strategy. For example, Hispanic families value “la familia” or familism, a strong commitment to family life that stresses the importance of the family group over the interest of an individual. Hispanic families are more likely than White families to live in extended family groups, share economic resources, and encourage reciprocity and solidarity (Landale et al. 2006). La familia creates belonging.

7.4.2 Conflict Theory

Rather than examining the functions of a family, conflict theorists look at power and inequality related to families. They connect the economics of capitalism with the institution of the family. They argue that, like the concept of private property in capitalism, families are also private. This idea is captured by the saying, “A man’s home is his castle,” the patriarchal idea that men should run their families without interference. According to conflict theorists, the family can be a way to reproduce class inequalities (Calder 2016). As we discussed in Chapter 5, children of wealthy families usually have access to better education than children of poor families. Additionally, education itself contributes to sustaining wealth. Conflict theorists link family and class.

More recently, conflict theorists say that families differ in their experiences of family autonomy, the ability of a family to make their own decisions about their future or about the treatment of their members (Calder 2016). The idea of family autonomy is often championed by politically conservative people. They argue that a family has its own integrity. Families should not be subject to the intervention of the state. Parents should be able to make decisions for their children, like whether or not to be immunized, without the county health department or the school board requiring compliance. However, liberal and radical protesters also support family autonomy, like the protesters in Figure 7.24.

Figure 7.24. Protesters with signs that say Families belong together, including Migui Adams (center) who wears a shirt referencing Melania Trump’s controversial jacket.

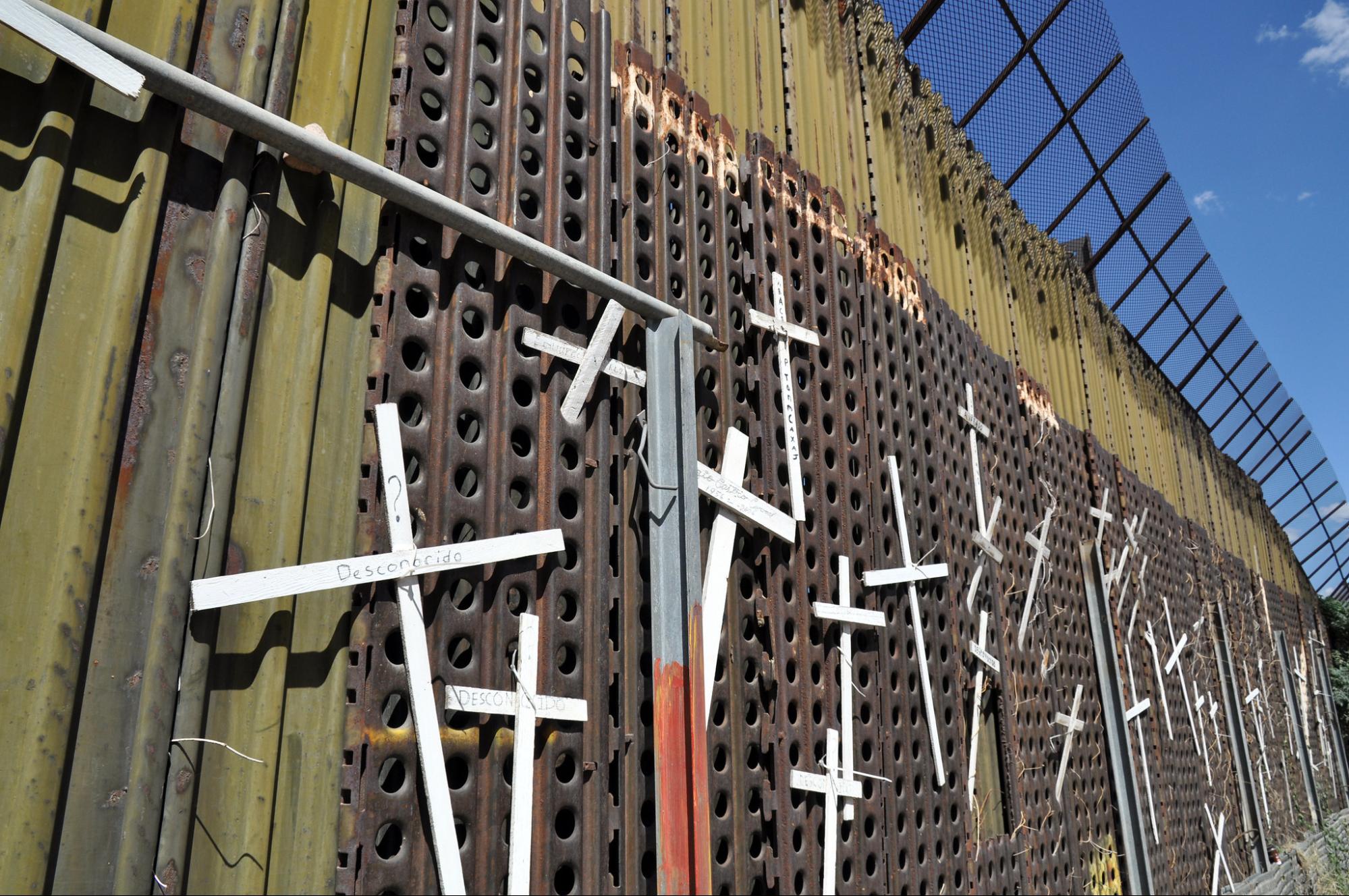

A second sociological concept that helps us understand how power and belonging are related, is the idea of the immigration industrial complex. “The immigration industrial complex is the confluence of public and private sector interests in the criminalization of undocumented migration, immigration law enforcement, and the promotion of “anti-illegal” rhetoric (Golash-Boza 2009:295).” Like the military industrial complex and the prison industrial complex that we mentioned in Chapter 1, the immigration industrial complex criminalizes, detains, and deports undocumented immigrants. Conflict sociologists look at who benefits from these actions. Although some of the original work related to the military-industrial complex comes from functionalist sociologists, conflict theories have deepened this work.

In this analysis, we see economic and social forces at work. On the one hand, the number of available immigrant visas is very low. However, businesses in the United States are dependent on low-wage workers to sustain their profits.

The undocumented labor force constitutes nearly 5 percent of the civilian labor force in the United States. This includes 29 percent of all agricultural workers, 29 percent of all roofers, 22 percent of all maids and housekeepers, and 27 percent of all people working in food processing. Without this undocumented labor force, it is likely that food grown in the United States would be grown elsewhere, thereby raising prices for consumers. (Golash-Boza 2009:306)

With high labor force numbers, it would seem useful to reform immigration laws so that people could come here legally. Instead, the United States has invested in a War on Terror similar to the War on Drugs that we will discuss in Chapter 11. The Department of Homeland Security, which houses the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), had a budget of over 1 trillion dollars for a 20-year period. The number of agents and officers dedicated to immigration and border protection has almost doubled between 2003 and 2019. The related agency budgets increased similarly. This money supports increased detaining and deporting of undocumented people in ways that often violate their human rights (Golash-Boza 2009).

Figure 7.25. This image shows the border wall between the United States and Mexico at Nogales, Mexico. The white crosses contain the names of people who have died while trying to cross the border. Who benefits when border crossings are restricted?

Sociologist Tanya Golash-Boza summarizes the connection between money, power, and oppression. She compares the military industrial complex, the prison industrial complex and the immigration industrial complex in this way:

These three complexes share three major features: (a) a rhetoric of fear; (b) the confluence of powerful interests; and (c) a discourse of other-ization. With the military build-up during the Cold War, the ‘others’ were communists. With the prison expansion of the 1990s, the ‘others’ were criminals (often racialized and gendered as black men). With the expansion of the immigration industrial complex, the ‘others’ are ‘illegals’ (racialized as Mexicans). In each case, the creation of an undesirable other creates popular support for government spending to safeguard the nation. (Golash-Boza 2009:306)

By examining money and power, conflict theories focus on why inequality in belonging occurs. Internal family violence, lack of bodily autonomy and the immigration industrial complex are all measures of conflict.

7.4.3 Symbolic Interactionism

You may remember theories of symbolic interactionist from Chapter 3. As a reminder, symbolic Interactionists view the world in terms of symbols and the meanings assigned to them (LaRossa and Reitzes 1993). The family itself is a symbol. To some, it is a father, mother, and children; to others, it is any union that involves respect and compassion. Interactionists stress that family is not an objective, concrete reality. Like other social phenomena, it is a social construct that is subject to the ebb and flow of social norms and ever-changing meanings.

Using symbolic interactionism, sociologists examine how queer families “do gender.” For example, in same-sex couples, there isn’t a mother and a father. That is to say, there isn’t a male person to work outside the home and make money, and a female person inside the home caring for children. Therefore, in a same-sex or gender-fluid pairing, the couple negotiates who does what. Family roles are no longer tied to gender. They are negotiated related to the skills, abilities, and needs of each person in the family. The family does gender every day, with the choices that they make about who pays bills, who changes diapers, and who takes out the trash.

7.4.4 Intersectional Theories of Belonging: Feminism, Critical Race Theory, and Queer Theory

Beyond the classical theories of family and belonging from functionalists, conflict theorists, and symbolic interactionists, there are queer theorists, feminist theorists, and critical race theorists who explain the social problem of belonging and family. They challenge traditional ideas of family and power, arguing that our changing family structures demonstrate resistance to patriarchy, racism, classism, and heteropatriarchy.

Heteropatriarchy is a system of oppression designed to reproduce and reinforce the dominance of heterosexual cisgender men and oppress women and LGBTQIA+ people (Everett et al. 2022). Family and belonging are contested in society. This territory is a fertile ground for social problems.

Queer theorists challenge the idea that marriage and family are the only healthy ways to be in a relationship. Early in queer political activism, many lesbians and gay men argued that it was important to explore non-heteropatriarchal relationships. Marriage itself was illegal, so many queer people formed families of choice. Queer theorists also explore how queer people choose families.

A chosen family is a deliberately chosen group of people that satisfies the typical role of family as a support system. These people may or may not be related to the person who chose them. These family groups are connected by conscious decision and lived experience rather than biology, adoption, or legalized relationships. Gay men and lesbian women often construct families of choice to create social resilience because many queer people are kicked out of their families of origin (Levin et al. 2020). Some of the original research related to families of choice was conducted during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s. To take care of each other, queer folk created families of choice to get groceries, take care of the sick, or bury the dead, like a family of origin might (Jackson Levin et al. 2020).

Feminist theories of the family argue that society is structured to privilege men over women; the theory works to understand and transform inequalities. This theory emphasizes how gender roles are constructed within the family, including the socialization of children. Feminist theorists also assert that resistance to patriarchal family structures is an important way to address inequality in social problems.

Figure 7.26. Please watch this 2:03-minute video explaining bodily autonomy [YouTube]. How does having bodily autonomy support social justice? Transcript

Feminist theorists and activists assert that bodily autonomy is necessary for women’s and non-binary people’s full participation in society. It is a relatively new term. To learn more, please watch the video in Figure 7.26. In a 2021 report, the United Nations defines bodily autonomy in this way:

The right to the autonomy of our bodies means that we have the power and agency to make choices, without fear of violence or having someone else decide for us. It means being able to decide whether, when, or with whom to have sex. It means making your own decisions about when or whether you want to become pregnant. It means the freedom to go to a doctor whenever you need one. (Erken 2021:7)

As we look at this definition, we see the ability to choose, for example, whether or when to have sex or to be pregnant. One woman said, “Being able to control when or if we have children is essential to the freedom of the women in this nation. Without bodily autonomy, we are not free (Judge et al. 2017:7). To be free from violence or coercion implies that we have a society that intervenes in violence, creating safety. It means creating a society that values women’s lives.

Also, as we examine the last element of this definition, we notice that people need access to health care. As we will discuss in Chapter 10, our personal choices impact our health. However, the social determinants of health, like access to healthy food, healthy environments, and good doctors that also support bodily autonomy.

These ideas about bodily autonomy can be applied more widely than just reproductive rights.

For example, in a 2022 master’s thesis, sociologist Nykayia King examines the experience of bodily autonomy for Black queer youth. She argues that state-sanctioned violence is the most visible layer of the deeper structural problem of racism. She writes, “…we must go beyond simple analysis of police behavior and reform and instead we must confront the roots of the problem, which are racism, white supremacy, and dehumanization.” (King 2022).

For example, Black queer youth experience a lack of bodily autonomy. In addition to racism and patriarchy, they are at risk because they are queer. Racism, sexism, and heteropatriarchy limit their bodily autonomy.

However, these Black queer youth also resist these challenges to their bodily autonomy. One young Black queer person, Kahlil, was taught by his uncle to “walk with a purpose” Kahlil says:

And I guess it’s because he grew up in that time where it was a lot of oppression that he went through he’s like all right when you’re walking somewhere, walk with a purpose, so like, walk with your head up like, you’re going somewhere like you have somewhere to be. So yeah, whenever I’m around, and I know there’s cops, like, on the street and stuff I turn from like, if I’m just chilling, I’m just enjoying my day walking, I start walking more so with a purpose to make it seem like, I’m not just- I don’t even know what the word would be loitering? I don’t know. Um, so there’s no reason for them to stop me and ask questions or anything like that. (King 2022:45-46)

Explaining this, King writes that although “walking with a purpose” was useful for Kahlil, it also limited his bodily autonomy, because this action was a choice to survive, not a choice to be authentic.

Finally, Black transgender youth experienced gender dysphoria, a specific lack of bodily autonomy, when talking to the police. When the police misgendered them, they did not feel safe enough to correct the police about their pronouns. A Black transgender youth said that they deliberately dressed and acted in a more feminine way to try to avoid trouble. They say:

If I’m dressed more masculine, then I’m going to be perceived as a Black man and a threat. If I’m dressed more feminine, which that happens sometimes, then I’m going to be perceived as a Black woman, someone who they could do whatever to. It may not be a threat, but they can still treat me in whatever way, and what can I do about it? (King 2022:51)

King concludes that Black people in general and Black queer youth specifically lack bodily autonomy because of racism and police violence. The more marginalized identities they held, the less autonomy they experienced. At the same time, many of the respondents used deliberate strategies to increase their agency in challenging circumstances, such as”walk with purpose” or acting more feminine.

Through this concept of bodily autonomy, we can examine the social problem of belonging with an intersectional lens. When we do, we see that people and families experience discrimination and violence in different ways based on their gender identity, sexuality, race, and class. White supremacy, patriarchy, heteropatriarchy, and systems of economic inequality remove bodily and family autonomy through violence.

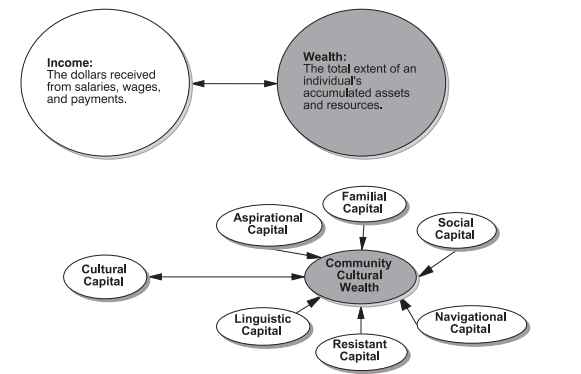

Figure 7.27. Community Cultural Wealth is the interdependent overlapping forms of knowledge, skills, abilities, and networks possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist racism and other forms of subordination (Yosso 2023) Other than income and wealth, what resources do you bring to support your family’s belonging? Image Description

However, the family can be a source of strength for its members. Educator and researcher Tara Yosso expands on this idea. She argues that students of color draw upon community cultural wealth, the interdependent overlapping forms of knowledge, skills, abilities and networks possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist racism and other forms of subordination (Yosso 2023). One of the components supporting community cultural wealth is familial capital. Yosso writes:

Acknowledging the racialized, classed, and heterosexualized inferences that comprise traditional understandings of ‘familia”, familial capital is nurtured by our ‘extended family’, which may include immediate family (living or long passed on) as well as aunts, uncles, grandparents, and friends who we might consider part of our familia. From these kinship ties, we learn the importance of maintaining a healthy connection to our community and its resources. Our kin also model lessons of caring, coping and providing (educación), which inform our emotional, moral, educational and occupational consciousness (Yosso 2006:79).

The family itself can be a source of power for People of Color to resist White supremacy and thrive despite economic and social inequality. Yosso’s model is a powerful critique of previous models of social capital. If you’d like to read her work directly, please see: Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.

7.4.5 Licenses and Attributions for Explaining the Social Problem of Belonging

Open Content, Original

“Explaining the Social Problem of Belonging” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Structural Functionalism,” “Conflict Theory,” and “Symbolic Interactionism” from “Variations in Family Life” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Intersectional Theories of Belonging: Feminism, Critical Race Theory, and Queer Theory” is partially adapted from “Core Theories” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, “Theories, Perspectives, and Key Concepts,” Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Chosen Family” definition is adapted from Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach by Deborah P. Amory, Sean G. Massey, Jennifer Miller, and Allison P. Brown, State University of New York, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.25. “Wall of Crosses” by Jonathan McIntosh is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Community Cultural Wealth” definition from personal communication with Tara Yosso, all rights reserved and used with permission.

Figure 7.24. “Photo” by Eman Mohammed from “For Women At D.C.’s ‘Families Belong Together,’ The Protest Was Personal” © NPR is included under fair use.

Figure 7.26. “Understanding Bodily Autonomy” by Diversity for Social Impact is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.27. “Community Cultural Wealth” from “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth” by Tara J. Yosso, Race Ethnicity and Education, © Taylor & Francis Group Ltd is included under fair use. Yosso recommended using this image in a personal email communication.