5.3 Models of Education: Applying the Social Problems Process

Kimberly Puttman

When we examine how our students perform in school—how many grades students attend school; whether they can read, write, reason critically, or use computers; whether they graduate from high school or end up at NASA or being brain surgeons—we see a difference between wealthy White male students and those who are not. The achievement gap refers to any significant and persistent disparity in academic performance or educational attainment between different groups of students, such as White students and students of color, for example, or students from higher-income and lower-income households (Great Schools Partnership 2013).

In some good news related to a social problem, the achievement gap between women and men is closing. Colleges and universities in the United States enroll at least as many women as men and more women than men appear to be graduating (Parker 2021). However, differences in educational outcomes persist when you examine the trends using race and class. When you apply intersectional analysis to education, like the d/Deaf Black students in the previous section, the differences in outcomes become even more pronounced. To explain this, we examine the history of who is educated over time and how educational policy has expanded access to education (somewhat).

5.3.1 Legal Segregation

To make informed decisions, people need the ability to read and write. A literate populace was fundamental to establishing a strong democracy. Access to education expanded in the 1700s and 1800s. Despite this intention, we haven’t yet achieved universal access to education, which is people’s equal ability to participate in an education system.

Early education systems in the United States were segregated. Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions. Schools were segregated by gender, race, ability/disability, and class. Educator and researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings summarizes the history of segregation in education in the United States (2006). She writes:

In the case of African Americans, education was initially forbidden during the period of enslavement. After emancipation, we saw the development of freedmen’s schools whose purpose was the maintenance of the servant class. During the long period of legal apartheid, African Americans attended schools where they received cast off textbooks and materials from White school. . . . Black students in the south did not receive universal secondary education until 1968.” (Ladson-Billings 2006:5, emphasis added)

As already discussed in this chapter, the US federal government policies required that Indigenous children stay in residential schools just for them. Finally, d/Deaf students, when they could access education, received that education in segregated facilities, usually in state boarding schools. In these schools, students were often taught to lip read and speak, preparing them to interact in a hearing world rather than respecting d/Deaf culture. Additionally, Mexican and other Spanish-speaking children experienced segregation. In Texas and California, 80% of the school districts were legally segregated (Arce 2021). Other states practiced informal segregation that was no less harmful.

Even when education was legal for many marginalized groups, it was provided in separate, segregated facilities that often (but not always) provided lower-quality education. This history of inequality is the deep roots of unequal educational outcomes, a precondition for a social problem.

5.3.2 Legal Integration

The educational goal for many families was to end legal segregation. For example, in 1931, a Californian Hispanic family sued that school district because students were segregated based on having Hispanic-sounding last names. This was the first case where educational segregation was declared illegal in a federal court (Arce 2021).

Segregation became more widely illegal in the United States with the US Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Brown declared that separating children based on race in school was illegal. This change in federal law launched passionate and often violent conflicts to integrate schools. In addition to the stories you may already know, desegregation also occurred with Latinx students. If you’d like to learn more, feel free to watch this video, Austin Revealed: Chicano Civil Rights “Desegregation & Education” [Video], in which students talk about their experiences with segregation and desegregation.

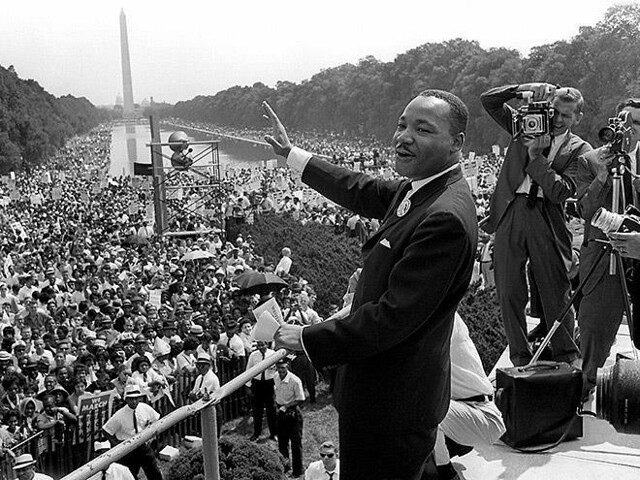

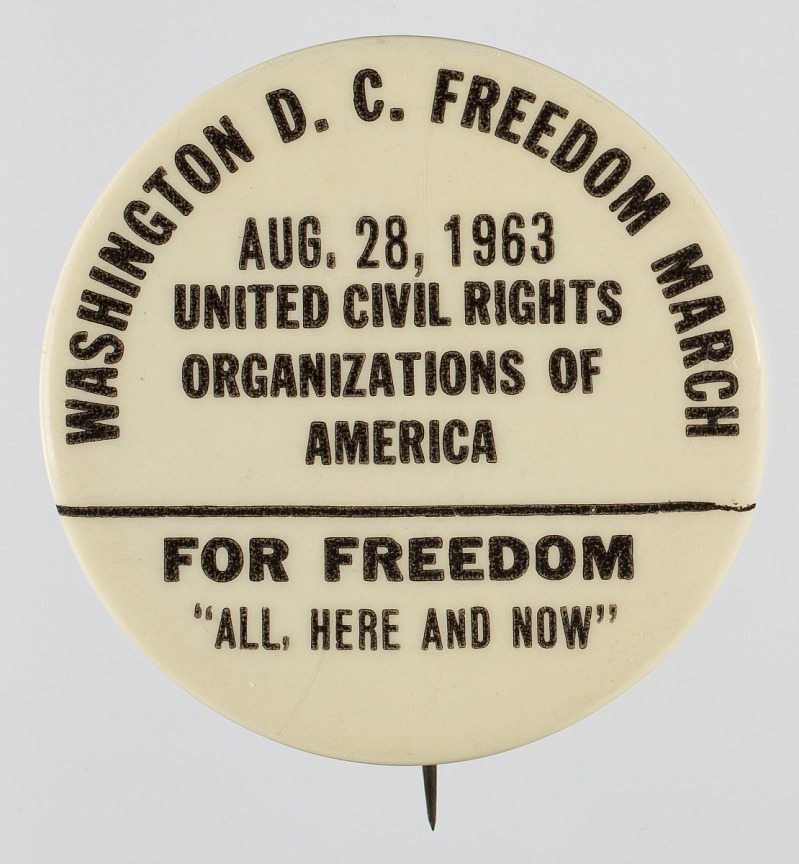

Figure 5.15 a and b. A) Martin Luther King Jr. at the Freedom March. B) A button from the Washington DC Freedom March of 1963. Activists marched to expand protections to prohibit discrimination. Do you know of other examples of protest and art that creates social justice in education?

Since 1954, many laws that move from segregated to integrated education have been passed. In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin. Title IV of this act prohibits segregation in schools. Title VI of this act prohibits discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin for any programs that receive federal funds, including schools and colleges. The educators at Learning for Justice describe Title VI as “one of the biggest victories of the civil rights movement” (Collins 2019). These legal changes resulted from fierce activism by Black, Brown, and White people. You can see leaders, activists, and a button from the related Freedom March in figures 5.15 a and b. Also, you have the option of exploring Learning for Justice more if you wish.

In separate legislation, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 stated:

No person in the United States shall, based on sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance (United States Congress 1972).

Title IX opened the doors of education even wider to women because colleges could no longer use gender as a reason to admit or fail to admit students. It also resulted in funding for women and women’s sports. More recently, this amendment protected LGBTQIA+ students from discrimination in public and private schools, at least legally.

When we apply the social problems process from Chapter 1, we see that legal integration results from steps 1 – 3: claimsmaking, media coverage, and public reaction. Finally, the federal government acted to change the law, which is Step 4: Policy making. The government, in the form of the legislature and US Supreme Court, creates and upholds laws that expand access to education. Although our school systems fall short of equal outcomes, in law, at least, people of all races, ethnicities, classes, genders, and ages can learn together.

5.3.3 De-facto Segregation

Changes in federal and state laws are only one step in addressing a social problem. Policymakers must implement those laws, and communities, families, and individuals must respond to them. This is step 5, Social Problems Work, in the social problem process.

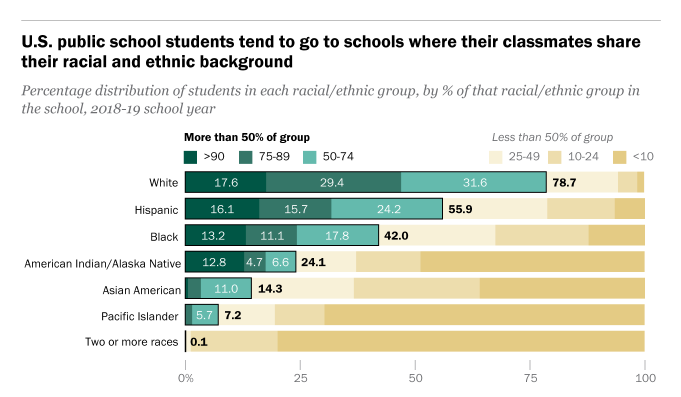

Figure 5.16. This chart shows that educational segregation still exists, even though it is illegal. Most White children go to school with White children. Most Hispanic children go to school with Hispanic children. Figure 5.16 Image Description

Educational segregation is illegal, but many schools and school districts are de-facto segregated, due to a history of redlining, which we discuss in Chapter 6. In a recent analysis of US Department of Education data, Pew Research reports that most students attend schools that serve other students of their race and ethnicity (Figure 5.16). In other words, White students are likely to attend schools where half or more of the other students are also White. Hispanic students are also likely to attend schools where at least half of the other students are Hispanic. For other racial groups, the proportions are slightly smaller, partially because the numbers of people who make up those groups are smaller as well.

One reason for this segregation is that we tend to live in neighborhoods that are also segregated. Rich people, who are more often White, tend to live with other rich people. Because children commonly attend schools in their own neighborhoods, the schools mirror the lack of integration in neighborhood communities. The social problem of unequal access to education is not yet solved because the policy outcomes reflected as step six in the social problems process fall short of the mark.

While school segregation is against the law, segregated classrooms are alive and well.

5.3.4 Inclusion

In addition to prohibiting segregation based on race, ethnicity, color, and gender, federal law requires that students labeled as disabled receive equitable education and educational support. Discrimination against differently-abled people became illegal with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990.

To ensure equitable education, schools began to integrate classrooms. This practice, known as inclusion, moves disabled students from residential schools and separate classrooms into inclusive classrooms. Inclusion is also commonly called mainstreaming, a unique type of integration.

In one example of inclusion supported by law, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EHC) of 1975 included deafness as one of the categories under which children with disabilities may be eligible for special education and related services. This law required public schools to provide educational services to disabled children ages three to twenty one. This law included d/Deaf students as disabled under the law, expanding the services available to them and increasing integration.

As we look at inclusion, we see the interplay inherent in the social problems process. Interested people argue for what they think is right during step three of public reaction. The government responds through policymaking. The outcomes fall short of the desire, and new claims are made.

5.3.5 Educational Debt not Achievement Gap

Achievement gaps based on social location persist. As researchers and community members, we can note the facts, but the more important question is why? Understanding the complex causes of this persistence may help us act in ways that will close the gap. If our education is intended to be universal, all students must have equal access and outcomes not based on social identity or social location.

Figure 5.17. Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, educator and educational researcher. She argues that we need to examine educational debt, rather than focusing on the achievement gap.

Gloria Lasdon-Billings, who you first learned about in the section about legal segregation, is an educator and an educational researcher (Figure 5.17). As the president of American Educational Research Association (AERA), she gave the presidential address in 2006. She examines the achievement gap and explores what makes the most effective teacher, particularly those teachers who can close the achievement gap for Black students. If you would like to learn more about her, read this article: Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to Dream in Public.

In her 2006 presidential address, Ladson-Billings argues that sociologists should study educational debt rather than the achievement gap. Educational debt is the cumulative impact of fewer resources and other harm directed at students of color. This education debt includes economic, sociopolitical, and moral characteristics.

Economically, educational debt consists of unequal spending in education over centuries. Segregation supported economic inequality in education. Today, because schools are funded based on population and property tax revenues, schools in rich neighborhoods, which are more likely to be White, spend more on each individual child’s education.

Sociopolitically, we see the exclusion of Black and Brown people from voting. They are also excluded from decision-making in school districts, state houses, and the federal government. For example, in 2018, 78% of school board members were White, even though 50% of all public school students are not White (Bland 2022, National School Boards Association 2018). Families of color are excluded from power in education.

Finally, Ladson-Billings argues that education is experiencing moral debt. She writes, “A moral debt reflects the disparity between what we know and what we actually do” (Ladson-Billings 2006:8). She further asks:

What is it that we might owe to citizens who historically have been excluded from social benefits and opportunities? Randall Robinson (2000) states: No nation can enslave a race of people for hundreds of years, set them free bedraggled and penniless, pit them, without assistance in a hostile environment, against privileged victimizers, and then reasonably expect the gap between the heirs of the two groups to narrow. Lines begun parallel and left alone, can never touch. (Ladson-Billings 2006:8)

In the end, she argues that the achievement gap is a result of educational debt. Further, educational debt is caused by the wider social forces of systemic racism, poverty, and health inequities rather than the cause of the inequality itself. If you want to learn more about the experience of educational debt, please watch “How America’s Public Schools Keep Kids in Poverty

.”

5.3.6 Equity

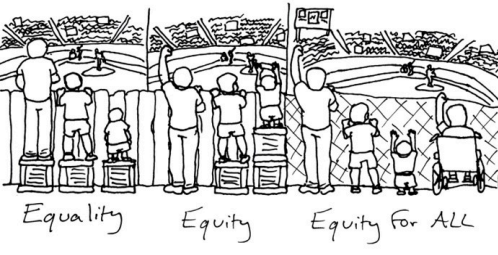

Although generational educational debt cannot be solved by simple answers, equity rather than equality can be part of an effective response. Equity is defined as everyone having what they need, even if it means that some need to be given more to get there. The drawing in Figure 5.18 illustrates the difference. You may have seen different variations of this concept as memes on social media. If you’d like to read more about it, this blog has a good explanation.

Figure 5.18. Equality, Equity, Equity for all. (Contemporary Families). Figure 5.18 Image Description

The drawing explores what it takes to give each person what they need to enjoy the game. In the first panel of the drawing, they do not all get to have an equal experience. In the second drawing, the participants can have the viewing experience because the boxes have been equitably distributed. The third panel removes the structure that limits equitable access so that all participants can view the game without additional resources. The viewers get what they need easily—they have equity for all.

5.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for Models of Education

Open Content, Original

“Models of Education” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Equity” definition from Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press] by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Equity section” is adapted from “Equity, Equality, and Fairness” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.15a. “Martin Luther King Jr. at the Freedom March” by the National Parks Service is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 5.18. “Equality, Equity, Equity for All” by Katie Niemeyer from “Equity, Equality, and Fairness” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.15b. “Button from Washington DC Freedom March” from the Smithsonian National Museum is included under fair use.

Figure 5.16. “US public school students tend to go to schools where their classmates share their racial and ethnic” from “US public school students often go to schools where at least half of their peers are the same race or ethnicity” by Katherine Schaeffer © Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. is licensed under the Center’s Terms of Use.

Figure 5.17. “Image of Gloria Ladson-Billings” by Marcus Miles from “Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to dream in public” by Käri Knutson, University of Wisconsin-Madison is included under fair use.